Time, Infinity, Recursion, and Liminality in the Writings of Jorge Luis Borges

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Crimson Hexagon. Books Borges Never Wrote

Allen Ruch The Crimson Hexagon Books Borges Never Wrote “The composition of vast books is a laborious and impoverish- ing extravagance. To go on for five hundred pages developing an idea whose perfect oral exposition is possible in a few min- utes! A better course of procedure is to pretend that these books already exist, and then to offer a resume, a commen- tary… More reasonable, more inept, more indolent, I have preferred to write notes upon imaginary books.” (Jorge Luis Borges). he fiction of Borges is filled with references to encyclopedias that do not exist, reviews of imaginary books by fictional au- T thors, and citations from monographs that have as much real existence as does the Necronomicon or the Books of Bokonon. As an intellectual exercise of pure whimsical uselessness, I have cata- logued here all these “imaginary” books that I could find in the stories of the “real” Argentine. I am sure that Borges himself would fail to see much of a difference… Note: In order to flesh out some of the details, I have elaborated a bit - although much of the detail on these books is really from Borges. I have added some dates, some information on contents, and a few general descriptions of the book’s binding and cover; I would be more than happy to accept other submissions and ideas on how to flesh this out. Do you have an idea I could use? The books are arranged alphabetically by author. Variaciones Borges 1/1996 122 Allen Ruch A First Encyclopaedia of Tlön (1824-1914) The 40 volumes of this work are rare to the point of being semi- mythical. -

The Exhibition/Pintando a Borges: La Exhibición Jorge J

topics 3 identity and memory • freedom and destiny • faith and divinity art Interpreting literature VolumePa 1 • Number i 1 n • A Publication t of University at Buffalo Art Galleries ingBORGES THE EXHIBITION/PINTANDO A BORGES: LA EXHIBICIÓN Jorge J. E. Gracia Numerous examples of the hermeneutic phenomenon that work has had a most evident impact. This is particularly concerns us are found in the history of art and could have true of artists who are porteños, born and raised in Buenos served our purpose. Why not use Michelangelo, Leonardo, Aires, for Borges is quintessentially a porteño. or Goya? One reason is that the variety of literary works these artists interpreted is too large, creating unnecessary It was not difficult to find the artists. But a variety of complications and distractions. Moreover, the use of perspectives also required the inclusion of non-Argentinean religious stories and myths, so common in the history of art, artists. I found the key in José Franco, a Cuban artist who add difficulties that further complicate matters. It is one thing resides in Buenos Aires and had produced works based to interpret a literary text that has no religious overtones, on Borges’ stories. The idea of including him appeared and another to interpret one that believers consider a divine appropriate in that it would reveal how an “adopted revelation. Then there is the exhaustive and numerous Argentinean” would approach Borges. In turn, this led us to discussions of these works by critics throughout history. To other Cubans. Finally, in order to maintain unity and focus, pick a work such as Michelangelo’s pictorial interpretation and to avoid difficulties with space and transportation, I of Genesis in the Sistine Chapel would have forced us to restricted the art work to paintings, drawings, etchings, and deal with many issues that are only marginally related to mixed media, all on a flat format, and so had to leave out the core topic of interest here. -

Dragonlore Issue 37 08-11-03

The bird was a Rukh and the white dome, of course, was its egg. Sindbad lashes himself to the bird’s leg with his turban, and the next morning is whisked off into flight and set down on a mountaintop, without having excited the Rukh’s attention. The narrator adds that the Rukh feeds itself on serpents of such great bulk that they would have made but one gulp of an elephant. In Marco Polo’s Travels (III, 36) we read: Dragonlore The people of the island [of Madagascar] report that at a certain season of the year, an extraordinary kind of bird, which they call a rukh, makes its appearance from The Journal of The College of Dracology the southern region. In form it is said to resemble the eagle but it is incomparably greater in size; being so large and strong as to seize an elephant with its talons, and to lift it into the air, from whence it lets it fall to the ground, in order that when dead it Number 37 Michaelmas 2003 may prey upon the carcase. Persons who have seen this bird assert that when the wings are spread they measure sixteen paces in extent, from point to point; and that the feathers are eight paces in length, and thick in proportion. Marco Polo adds that some envoys from China brought the feather of a Rukh back to the Grand Kahn. A Persian illustration in Lane shows the Rukh bearing off three elephants in beak and talons; ‘with the proportion of a hawk and field mice’, Burton notes. -

The Spectrum of Subjectal Forms: Towards an Integral Semiotics

Semiotica 2020; 235: 27–49 Sebastián Mariano Giorgi* The spectrum of subjectal forms: Towards an Integral Semiotics https://doi.org/10.1515/sem-2018-0022 Abstract: What is the relationship between consciousness and semiosis? This article attempts to provide some clues to answer this question. For doing it, we explore the application of the Integral model to semiotics; that is to say, the met- atheory that integrates the inside, the outside, the individual, and the collective dimension, on one hand and, on the other hand, the levels of development, states and types of consciousness. Our principal hypothesis is that the semiosis depends on the “subjectal” form where the self is located temporarily or permanently. To validate it, we analyze the way in which the universe of meaning changes between the self located below the subject (as a form), and the self located beyond of it. According to the Integral semiotics point of view outlined here, the relationship between consciousness and the meaning has to do with the reduction or expansion of the subjectal spectrum, and the trajectory of the self along of it. Keywords: integral theory, integral semiotics, consciousness, semiosis, subjectal forms 1 Introduction At present, there is a lot of development about perception (Petitot 2009; Darrault- Harris 2009; Dissanayake 2009). Unfortunately, we find almost nothing about the role of consciousness (and its structures and states) in semiosis – with the exception of Jean-François Bordron (2012). However, there is much research about consciousness and its relationship to the brain in the neurosciences (Berlucchi and Marzi 2019; Chennu et al. 2009; Demertzi and Whitfield-Gabrieli 2016; Murillo 2005). -

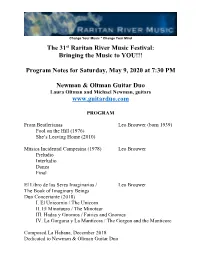

Program Notes for Saturday, May 9, 2020 at 7:30 PM Newman

Change Your Music * Change Your Mind The 31st Raritan River Music Festival: Bringing the Music to YOU!!! Program Notes for Saturday, May 9, 2020 at 7:30 PM Newman & Oltman Guitar Duo Laura Oltman and Michael Newman, guitars www.guitarduo.com PROGRAM From Beatlerianas Leo Brouwer (born 1939) Fool on the Hill (1976) She’s Leaving Home (2010) Música Incidental Campesina (1978) Leo Brouwer Preludio Interludio Danza Final El Libro de los Seres Imaginarios / Leo Brouwer The Book of Imaginary Beings Duo Concertante (2018) I. El Unicornio / The Unicorn II. El Minotauro / The Minotaur III. Hadas y Gnomos / Fairies and Gnomes IV. La Gorgona y La Mantícora / The Gorgon and the Manticore Composed La Habana, December 2018 Dedicated to Newman & Oltman Guitar Duo Commissioned by Raritan River Music With the generous support of Jeffrey Nissim CYBERSPACE PERMIERE PERFORMANCE Composed in celebration of the 80th Anniversary Year of Leo Brouwer NOTES IN ENGLISH CAPTURING THE IMAGINARY BEINGS BY LAURA OLTMAN AND MICHAEL NEWMAN The guitar explosion in the United States in the 1960s was fueled by the influence of Cuban musicians, including the legendary Leo Brouwer, as well as Juan Mercadal, Elías Barreiro, Mario Abril, and our teachers Alberto Valdes Blain and Luisa Sánchez de Fuentes. We grew up playing the music of Leo Brouwer. In the early days of the Newman & Oltman Guitar Duo, we shared a booking agent with Brouwer, Sheldon Soffer Management. We often thought that a major duet by Maestro Brouwer would be a dream for our duo. We met Brouwer at his New York debut recital in 1978, which was co- sponsored by Americas Society. -

Abismo Logico.Pdf

Otros títulos de esta Colección EL ABISMO LÓGICO MANUEL BOTERO CAMACHO Este libro explora un fenómeno que se mencionar filósofos y escribir cuentos (BORGES Y LOS FFFEILOSOFEOS F DE LAS IDEAS) Doctor en Filología de la Universidad Complu- repite en algunos textos del escritor argen- acerca de una realidad imposible tense de Madrid con Diploma de Estudios Avan- tino Jorge Luis Borges (1899-1986). Está siguiendo sus filosofías, de mostrar algo MANUEL BOTERO CAMACHO GÉNESIS Y TRANSFORMACIONES MANUEL BOTERO CAMACHO zados en Filología Inglesa y en Filología Hispa- DEL ESTADO NACIÓN EN COLOMBIA compuesto por nueve capítulos, que acerca de sus creencias, sería precisa- noamericana. Licenciado en Literatura, opción UNA MIRADA TOPOLÓGICA A LOS ESTUDIOS SOCIALES DESDE LA FILOSOFÍA POLÍTICA corresponden al análisis de la reescritura mente su escepticismo respecto de en filosofía, de la Universidad de Los Andes, de nueve distintas propuestas filosóficas. dichas doctrinas. Los relatos no suponen Bogotá. Es profesor en la Escuela de Ciencias ADOLFO CHAPARRO AMAYA Las propuestas están cobijadas bajo la su visión de la realidad sino una lectura Humanas y en la Facultad de Jurisprudencia CAROLINA GALINDO HERNÁNDEZ misma doctrina: el idealismo. Es un libro de las teorías acerca de la realidad. (Educación Continuada) del Colegio Mayor de que se escribe para validar la propuesta Nuestra Señora del Rosario. Es profesor de de un método de lectura que cuenta a la El texto propone análisis novedosos de Semiología y Coordinador de los Conversato- COLECCIÓN TEXTOS DE CIENCIAS HUMANAS vez con una dosis de ingenio y con los cuentos de Borges y reevalúa y rios de la Casa Lleras en la Universidad Jorge planteamientos rigurosos, permitiendo critica algunos análisis existentes elabo- Tadeo Lozano. -

Ge Fei's Creative Use of Jorge Luis Borges's Narrative Labyrinth

Fudan J. Hum. Soc. Sci. DOI 10.1007/s40647-015-0083-x ORIGINAL PAPER Imitation and Transgression: Ge Fei’s Creative Use of Jorge Luis Borges’s Narrative Labyrinth Qingxin Lin1 Received: 13 November 2014 / Accepted: 11 May 2015 © Fudan University 2015 Abstract This paper attempts to trace the influence of Jorge Luis Borges on Ge Fei. It shows that Ge Fei’s stories share Borges’s narrative form though they do not have the same philosophical premises as Borges’s to support them. What underlies Borges’s narrative complexity is his notion of the inaccessibility of reality or di- vinity and his understanding of the human intellectual history as epistemological metaphors. While Borges’s creation of narrative gap coincides with his intention of demonstrating the impossibility of the pursuit of knowledge and order, Ge Fei borrows this narrative technique from Borges to facilitate the inclusion of multiple motives and subject matters in one single story, which denotes various possible directions in which history, as well as story, may go. Borges prefers the Jungian concept of archetypal human actions and deeds, whereas Ge Fei tends to use the Freudian psychoanalysis to explore the laws governing human behaviors. But there is a perceivable connection between Ge Fei’s rejection of linear history and tradi- tional storyline with Borges’ explication of epistemological uncertainty, hence the former’s tremendous debt to the latter. Both writers have found the conventional narrative mode, which emphasizes the telling of a coherent story having a begin- ning, a middle, and an end, inadequate to convey their respective ideational intents. -

1 Jorge Luis Borges the GOSPEL ACCORDING to MARK

1 Jorge Luis Borges THE GOSPEL ACCORDING TO MARK (1970) Translated by Norrnan Thomas di Giovanni in collaboration with the author Jorge Luis Borges (1899-1986), an outstanding modern writer of Latin America, was born in Buenos Aires into a family prominent in Argentine history. Borges grew up bilingual, learning English from his English grandmother and receiving his early education from an English tutor. Caught in Europe by the outbreak of World War II, Borges lived in Switzerland and later Spain, where he joined the Ultraists, a group of experimental poets who renounced realism. On returning to Argentina, he edited a poetry magazine printed in the form of a poster and affixed to city walls. For his opposition to the regime of Colonel Juan Peron, Borges was forced to resign his post as a librarian and was mockingly offered a job as a chicken inspector. In 1955, after Peron was deposed, Borges became director of the national library and Professor of English Literature at the University of Buenos Aires. Since childhood a sufferer from poor eyesight, Borges eventually went blind. His eye problems may have encouraged him to work mainly in short, highly crafed forms: stories, essays, fables, and lyric poems full of elaborate music. His short stories, in Ficciones (1944), El hacedor (1960); translated as Dreamtigers, (1964), and Labyrinths (1962), have been admired worldwide. These events took place at La Colorada ranch, in the southern part of the township of Junin, during the last days of March 1928. The protagonist was a medical student named Baltasar Espinosa. We may describe him, for now, as one of the common run of young men from Buenos Aires, with nothing more noteworthy about him than an almost unlimited kindness and a capacity for public speaking that had earned him several prizes at the English school0 in Ramos Mejia. -

Postmodern Or Post-Auschwitz Borges and the Limits of Representation

Edna Aizenberg Postmodern or Post-Auschwitz Borges and the Limits of Representation he list of “firsts” is well known by now: Borges, father of the New Novel, the nouveau roman, the Boom; Borges, forerunner T of the hypertext, early magical realist, proto-deconstructionist, postmodernist pioneer. The list is well known, but it may omit the most significant encomium: Borges, founder of literature after Auschwitz, a literature that challenges our orders of knowledge through the frac- tured mirror of one of the century’s defining events. Fashions and prejudices ingrained in several critical communities have obscured Borges’s role as a passionate precursor of many later intellec- tuals -from Weisel to Blanchot, from Amery to Lyotard. This omission has hindered Borges research, preventing it from contributing to major theoretical currents and areas of inquiry. My aim is to confront this lack. I want to rub Borges and the Holocaust together in order to unset- tle critical verities, meditate on the limits of representation, foster dia- logue between disciplines -and perhaps make a few sparks fly. A shaper of the contemporary imagination, Borges serves as a touch- stone for concepts of literary reality and unreality, for problems of knowledge and representation, for critical and philosophical debates on totalizing systems and postmodern esthetics, for discussions on cen- ters and peripheries, colonialism and postcolonialism. Investigating the Holocaust in Borges can advance our broadest thinking on these ques- tions, and at the same time strengthen specific disciplines, most par- ticularly Borges scholarship, Holocaust studies, and Latin American literary criticism. It is to these disciplines that I now turn. -

Valeria Maggiore FANTASTIC MORPHOLOGIES: ANIMAL FORM

THAUMÀZEIN 8, 2020 Valeria Maggiore FANTASTIC MORPHOLOGIES: ANIMAL FORM BETWEEN MYTHOLOGY AND EVO-DEVO Table of Contents: 1. Imaginary beings and the rules of form; 2. The hundred eyes of Argos: Evo-Devo, evolutionary plasticity and historical constraints; 3. The wings of Pegasus: architectural constraints and mor- phospace; 4. Conclusions: from imaginary beings to fantastic beings. Perhaps universal history is the history of a few metaphors. J.L. Borges, Pascal’s Sphere, 1952. 1. Imaginary beings and the rules of form «It is the animal with the big tail, a tail many yards long and like a fox’s brush. How I should like to get my hands on this tail sometime, but it is impossible, the animal is constantly moving about, the tail is constantly being flung this way and that. The animal resembles a kangaroo, but not as to the face, which is flat almost like a human face, and small and oval; only its teeth have any power of expression, whether they are concealed or bared» [Borges 1974, 17]. With these words Franz Kafka describes a bizarre creature that appeared in his dreams: a hybrid in which the perspicuous characters of morphologically and ethologically different animals – such as the fox and the kangaroo – are mixed to human somatic traits, recalling ancient mythological beings [Borghese 2009, 283]. Jorge Luis Borges accurately transcribes the words of the Prague writer in his Book of Imaginary Beings [Borges 1974], a manual of fan- tastic zoology written in collaboration with María Guerrero in 1957 and 39 Valeria Maggiore inscribed in the literary tradition of medieval bestiaries. -

Select Bibliography

Select Bibliography by the late F. Seymour-Smith Reference books and other standard sources of literary information; with a selection of national historical and critical surveys, excluding monographs on individual authors (other than series) and anthologies. Imprint: the place of publication other than London is stated, followed by the date of the last edition traced up to 1984. OUP- Oxford University Press, and includes depart mental Oxford imprints such as Clarendon Press and the London OUP. But Oxford books originating outside Britain, e.g. Australia, New York, are so indicated. CUP - Cambridge University Press. General and European (An enlarged and updated edition of Lexicon tkr WeltliU!-atur im 20 ]ahrhuntkrt. Infra.), rev. 1981. Baker, Ernest A: A Guilk to the B6st Fiction. Ford, Ford Madox: The March of LiU!-ature. Routledge, 1932, rev. 1940. Allen and Unwin, 1939. Beer, Johannes: Dn Romanfohrn. 14 vols. Frauwallner, E. and others (eds): Die Welt Stuttgart, Anton Hiersemann, 1950-69. LiU!-alur. 3 vols. Vienna, 1951-4. Supplement Benet, William Rose: The R6athr's Encyc/opludia. (A· F), 1968. Harrap, 1955. Freedman, Ralph: The Lyrical Novel: studies in Bompiani, Valentino: Di.cionario letU!-ario Hnmann Hesse, Andrl Gilk and Virginia Woolf Bompiani dille opn-e 6 tUi personaggi di tutti i Princeton; OUP, 1963. tnnpi 6 di tutu le let16ratur6. 9 vols (including Grigson, Geoffrey (ed.): The Concise Encyclopadia index vol.). Milan, Bompiani, 1947-50. Ap of Motkm World LiU!-ature. Hutchinson, 1970. pendic6. 2 vols. 1964-6. Hargreaves-Mawdsley, W .N .: Everyman's Dic Chambn's Biographical Dictionary. Chambers, tionary of European WriU!-s. -

Politics of the Name: on Borges's “El Aleph”

POLITICS OF THE NAME: ON BORGES’S “EL ALEPH” w Silvia Rosman Todo lenguaje es un alfabeto de símbolos cuyo ejercicio presupone un pasado que los interlocutores comparten J. L. Borges, “El aleph” n reaction to the vitriolic attacks on the inhuman and foreign nature of his writing, from the 1920s on Borges explores the I question of a common language and its implications for the concept of literature. Is there an authentic Argentinean language that would give rise to an equally authentic national literature? In “El idioma de los argentinos” (1927), Borges responds to this ques- tion by referring to a double particularity: “Dos influencias antagó- nicas entre sí militan contra un habla argentina. Una es la de quienes imaginan que esa habla ya está prefigurada en el arrabalero de los sainetes; otra es la de los casticistas o españolados que creen en lo cabal del idioma y en la impiedad o inutilidad de su refacción” (Idioma 136). Neither the localized slang of the Buenos Aires margins and its implied unity of place, nor the linguistic cohesion of a dic- tionary Spanish that no one speaks succeed in capturing the “voice” of the Spanish spoken in Argentina, crystallized as those two “lan- guages” are by their proper and definite meaning. Variaciones Borges 14 (2002) 8 SILVIA ROSMAN If a certain cultural nationalism imposed the normalizing parame- ters that a pedagogical notion of an Argentinean essence embodied (the continuity with Hispanic tradition, the notion of authenticity and uniqueness that would mark the nation’s autonomy), Borges finds in the performative use of language a certain linguistic com- monality: the “no escrito idioma argentino (…) diciéndonos,” where the intonation or inflexion of certain words can be heard.