What the Riddle-Makers Have Hidden Behind the Fire of a Dragon

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Two Blind Men Describe “Bloody Good

Frame — a re-enactment of the assassination of John F. Kennedy. Twenty-two seconds of footage of the as- sassination, taken in Dallas in 1963 by Abra- ham Zapruda, was sold to Life magazine on the night of the shooting for $150,000. Life published stills from the film shortly after- wards. (Later, the Zapruda family would be paid $10 million by the US government for rights to the film). Stills were also re- produced in the Warren Commission Report of September 1964. The Warren Commis- sion also used the film as the basis for a se- ries of reconstructions that served as part of their investigation. The film itself was not broadcast until 1975. Perhaps more than any other, this moving image defined the turbu- lence of the 1960s for a wide American public during the 1970s. Don Delillo’s 1997 novel Underground cap- tures the sense of this moment in a fictional TIME account of one of the film’s first public, or semi-public, viewings in the summer of 1974. CAPTCHA’D The scene takes place in an apartment with television sets in every room. In each room a video of the same piece of footage plays, FOR GLOBAL with a slight delay. Delillo writes: “The event was rare and GOOD? strange. It was the screening of a bootleg copy of an eight-millimeter home movie that ran for twenty seconds. A little over twenty PALO ALTO — In 2002, Stanford Univer- seconds probably. The footage was known as sity launched a “community reading project” the Zapruda film and almost no one outside called Discovering Dickens, making Dickens’s the government had seen it. -

The Argonautica, Book 1;

'^THE ARGONAUTICA OF GAIUS VALERIUS FLACCUS (SETINUS BALBUS BOOK I TRANSLATED INTO ENGLISH PROSE WITH INTRODUCTION AND NOTES BY H. G. BLOMFIELD, M.A., I.C.S. LATE SCHOLAR OF EXETER COLLEGE, OXFORD OXFORD B. H. BLACKWELL, BROAD STREET 1916 NEW YORK LONGMANS GREEN & CO. FOURTH AVENUE AND 30TH STREET TO MY WIFE h2 ; ; ; — CANDIDO LECTORI Reader, I'll spin you, if you please, A tough yarn of the good ship Argo, And how she carried o'er the seas Her somewhat miscellaneous cargo; And how one Jason did with ease (Spite of the Colchian King's embargo) Contrive to bone the fleecy prize That by the dragon fierce was guarded, Closing its soporific eyes By spells with honey interlarded How, spite of favouring winds and skies, His homeward voyage was retarded And how the Princess, by whose aid Her father's purpose had been thwarted, With the Greek stranger in the glade Of Ares secretly consorted, And how his converse with the maid Is generally thus reported : ' Medea, the premature decease Of my respected parent causes A vacancy in Northern Greece, And no one's claim 's as good as yours is To fill the blank : come, take the lease. Conditioned by the following clauses : You'll have to do a midnight bunk With me aboard the S.S. Argo But there 's no earthly need to funk, Or think the crew cannot so far go : They're not invariably drunk, And you can act as supercargo. — CANDIDO LECTORI • Nor should you very greatly care If sometimes you're a little sea-sick; There's no escape from mal-de-mer, Why, storms have actually made me sick : Take a Pope-Roach, and don't despair ; The best thing simply is to be sick.' H. -

The Symbolism of the Dragon

1 THE SYMBOLISM OF THE DRAGON Chinese flying dragon (courtesy of dreamstime.com Ensiferrum 7071168) THE PRIMORDIAL SEVEN, THE FIRST SEVEN BREATHS OF THE DRAGON OF WISDOM, PRODUCE IN THEIR TURN FROM THEIR HOLY CIRCUMGYRATING BREATHS THE FIERY WHIRLWIND. The Stanzas of Dzyan Out of the whirlwind spoke the voice that ignites, that sounds like no voice ever heard. It is, instead, a flame that swirls down out of yawning darkness and scorches the flanks of the trembling world. Amongst the clouds gathered in storm, its fiery curves are sometimes glimpsed and the scraping of its taloned feet echo up the blackened caverns leading to the bowels of the earth. These are aspects of its voice . extensions of its flaming breath. They shine like glittering scales spiralling through the atmosphere. They project forth in the wake of that thunderous tone which issues from the depths of the very source of sound, from the primordial throat which opens out to another world. Thus it is that dragons float at the edge of the universe and near the apertures leading to unknown but frightening realms. Their fiery breath resounds and their reptilian form expands and contracts into myriad shapes described in thousands of stories the world over. But their exact nature remains a mystery and, despite their legendary reputation, for many persons they have never existed. It has been held that the dragon, "while sacred and to be worshipped, has within himself something still more of the divine nature of which it is better to remain in ignorance". Something double-edged is suggested here, and the question of the existence of the dragon deepens to become one of how to approach the Divine without being incinerated by its lower emanations. -

Solanaceae) Flower–Visitor Network in an Atlantic Forest Fragment in Southern Brazil

diversity Article Bee Diversity and Solanum didymum (Solanaceae) Flower–Visitor Network in an Atlantic Forest Fragment in Southern Brazil Francieli Lando 1 ID , Priscila R. Lustosa 1, Cyntia F. P. da Luz 2 ID and Maria Luisa T. Buschini 1,* 1 Programa de Pós Graduação em Biologia Evolutiva da Universidade Estadual do Centro-Oeste, Rua Simeão Camargo Varela de Sá 03, Vila Carli, Guarapuava 85040-080, Brazil; [email protected] (F.L.); [email protected] (P.R.L.) 2 Research Centre of Vascular Plants, Palinology Research Centre, Botanical Institute of Sao Paulo Government, Av. Miguel Stéfano, 3687 Água Funda, São Paulo 04045-972, Brazil; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] Received: 9 November 2017; Accepted: 8 January 2018; Published: 11 January 2018 Abstract: Brazil’s Atlantic Forest biome is currently undergoing forest loss due to repeated episodes of devastation. In this biome, bees perform the most frequent pollination system. Over the last decade, network analysis has been extensively applied to the study of plant–pollinator interactions, as it provides a consistent view of the structure of plant–pollinator interactions. The aim of this study was to use palynological studies to obtain an understanding of the relationship between floral visitor bees and the pioneer plant S. didymum in a fragment of the Atlantic Forest, and also learn about the other plants that interact to form this network. Five hundred bees were collected from 32 species distributed into five families: Andrenidae, Apidae, Colletidae, Megachilidae, and Halictidae. The interaction network consisted of 21 bee species and 35 pollen types. -

Jupiter and the Bee

Jupiter and the Bee At the beginning of time, the honeybee had no stinger. This left the bee with no way to protect her honey. The bee worked very hard to make her honey. But people were always taking it from her. This made the bee mad. The bee needed help. She needed a way to protect her honey. The bee decided to ask the gods for help. She took some of her best honey. Then she flew to Mount Olympus. That is where the gods lived. The bee went to see Jupiter. Jupiter was king of the gods. She brought him the honey as a gift. © 2018 Reading Is Fundamental • Content and art created by Simone Ribke Jupiter and the Bee Jupiter loved the honey. He had never tasted something so sweet. Jupiter said it was a great gift. In return, Jupiter promised to give the bee a gift. He asked her what she wanted. The bee asked Jupiter to give her a stinger. She would use it to keep people away from her honey. She would sting people who tried to take honey from her. Jupiter did not like this idea because he loved people. He did not want them to get stung. But he had made her a promise. Jupiter gave the bee a stinger, but using it came at a price. If she uses her stinger, she will die. The bee would have to choose. Will she protect her honey and die? Or will she let people take her honey and live? Jupiter gave stingers to all bees. -

Anne Meiring

UWE EBEL DARBIETUNGSFORMEN UND DARBIETUNGSABSICHT IN FORNALDARSAGA UND VERWANDTEN GATTUNGEN VORBEMERKUNG Der folgende Beitrag erschien zuerst 1982. Die mit ihm verfolgte Intention war es, ausgehend von den Graden der Fiktionalisierung des jeweils entfalteten Geschehens eine Differenz zwischen Íslendingasaga und Fornaldarsaga zu erarbeiten. Dabei hatte sich gezeigt, dass die Íslendingasaga trotz all der Momente, die sie als 'realistisch' erlebbar macht, das literarische Phänomen der Semantisierung von Form- elementen kennt, und dass die Fornaldarsaga trotz ihrer Phantastik solche Seman- tisierung nicht oder kaum aufweist. Ohne die mittelalterlichen Texte über jüngere und unangemessene Kriterien und Kategorien beschreiben zu wollen, ließe sich also ein Differenzmerkmal darin erblicken, dass die Íslendingasaga strukturell der Fiktion und die Fornaldarsaga strukturell dem Tatsachenbericht zuzuordnen sind. Erst im Verlauf der Gattungsgeschichte tritt in der Fornaldarsaga der Aspekt der Unter- haltung in den Vordergrund. Mit alledem soll nicht gesagt sein, dass der moderne Begriff der 'Literatur' dem originären Kontext gerecht wird, auch nicht, dass die Intention der Redaktoren und Traditoren damit beschrieben wäre. Das strukturelle Differenzmerkmal ist dennoch nicht zu verkennen und es gälte auszuwerten, was das über die fiktionale Gestaltung von Geschehen im isländischen Mittelalter besagt. Man sollte insgesamt berücksichtigen, dass eine als 'realistisch' erlebbare Literatur die sprachkünstlerische, oder besser die epische Ausdrucksform einer -

Dragonslayer Pdf, Epub, Ebook

DRAGONSLAYER PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Jennifer L Holm,Matthew Holm | 91 pages | 25 Aug 2009 | Random House USA Inc | 9780375857126 | English | New York, United States Dragonslayer PDF Book Oziach says that to be able to buy a rune platebody from him, you have to kill the green dragon , Elvarg , located on the desolate island of Crandor. Ignoring them, Rowan told Leaf about what the Dragonslayer did, and Leaf immediately wished to become a dragonslayer himself, but his parents strongly disapprove of the idea. Graphic artist David Bunnett was assigned to design the look of the dragon, and was fed ideas on the mechanics on how the dragon would move, and then rendered the concepts on paper. He was looking outside his window hoping that Wren would come back to The Indestructible City. Guts uses the empowered sword to deal a blazing blast to the Kundalini aiding Daiba, causing the magical beast's large water form to dematerialize. He is essential and will only fight for a short time before returning to his post. The screenplay was eventually accepted by Paramount Pictures and Walt Disney Productions , becoming the two studios' second joint effort after the film Popeye. Archived from the original on August 20, Kevin Thomas of the Los Angeles Times called Vermithrax "the greatest dragon yet", and praised the film for its effective evocation of the Dark Ages. Screen Rant. Wren and Sky saw a few sea dragons, and Sky suddenly exclaimed that Wren could ride on him. Massive, thick, heavy, and far too rough. Dragon Slayer is a free-to-play quest often regarded as the most difficult to free players. -

AN ABSTRACT of the THESIS of Miranda Renfro for the Master Of

AN ABSTRACT OF THE THESIS OF Miranda Renfro for the Master of Arts in English presented on 4 November 2014 Title: DYNAMIC DRAGONS: AN EXPLORATION OF ROLE REVERSAL IN THE YOUNG ADULT ADVENTURE CYCLE Abstract approved: ________________________________________________________ Dragons have long been a staple character in literary traditions all around the globe. From ancient Babylonian myth to modern young adult (YA) fiction, the dragon is well-represented within literature as a powerful and mysterious entity. Western culture, in particular, deems the dragon an evil enemy that must be overcome by a hero, while in Eastern cultures the dragon represents a much more natural and benevolent creature that generously bestows wisdom and wealth on worthy subjects. In recent years the stark character contrasts between the dragons of East and West have merged within the realm of Western YA literature to create a new kind of hero, one that still follows the path described by Joseph Campbell in The Hero with a Thousand Faces but challenges traditional perceptions of good and evil, especially where humanity is concerned. Young readers looking for answers to questions about their own identities within YA novels now have the opportunity to explore identity and human nature through the very eyes of the creature they were once taught to fear. Utilizing as a framework Campbell’s adventure cycle and goals found in modern YA literature, this thesis examines two YA novels that cast a dragon as the hero – Cornelia Funke’s Dragon Rider and Rachel Hartman’s Seraphina -

![Archons (Commanders) [NOTICE: They Are NOT Anlien Parasites], and Then, in a Mirror Image of the Great Emanations of the Pleroma, Hundreds of Lesser Angels](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/8862/archons-commanders-notice-they-are-not-anlien-parasites-and-then-in-a-mirror-image-of-the-great-emanations-of-the-pleroma-hundreds-of-lesser-angels-438862.webp)

Archons (Commanders) [NOTICE: They Are NOT Anlien Parasites], and Then, in a Mirror Image of the Great Emanations of the Pleroma, Hundreds of Lesser Angels

A R C H O N S HIDDEN RULERS THROUGH THE AGES A R C H O N S HIDDEN RULERS THROUGH THE AGES WATCH THIS IMPORTANT VIDEO UFOs, Aliens, and the Question of Contact MUST-SEE THE OCCULT REASON FOR PSYCHOPATHY Organic Portals: Aliens and Psychopaths KNOWLEDGE THROUGH GNOSIS Boris Mouravieff - GNOSIS IN THE BEGINNING ...1 The Gnostic core belief was a strong dualism: that the world of matter was deadening and inferior to a remote nonphysical home, to which an interior divine spark in most humans aspired to return after death. This led them to an absorption with the Jewish creation myths in Genesis, which they obsessively reinterpreted to formulate allegorical explanations of how humans ended up trapped in the world of matter. The basic Gnostic story, which varied in details from teacher to teacher, was this: In the beginning there was an unknowable, immaterial, and invisible God, sometimes called the Father of All and sometimes by other names. “He” was neither male nor female, and was composed of an implicitly finite amount of a living nonphysical substance. Surrounding this God was a great empty region called the Pleroma (the fullness). Beyond the Pleroma lay empty space. The God acted to fill the Pleroma through a series of emanations, a squeezing off of small portions of his/its nonphysical energetic divine material. In most accounts there are thirty emanations in fifteen complementary pairs, each getting slightly less of the divine material and therefore being slightly weaker. The emanations are called Aeons (eternities) and are mostly named personifications in Greek of abstract ideas. -

The Iconography of the Honey Bee in Western Art

Dominican Scholar Master of Arts in Humanities | Master's Liberal Arts and Education | Graduate Theses Student Scholarship May 2019 The Iconography of the Honey Bee in Western Art Maura Wilson Dominican University of California https://doi.org/10.33015/dominican.edu/2019.HUM.06 Survey: Let us know how this paper benefits you. Recommended Citation Wilson, Maura, "The Iconography of the Honey Bee in Western Art" (2019). Master of Arts in Humanities | Master's Theses. 6. https://doi.org/10.33015/dominican.edu/2019.HUM.06 This Master's Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Liberal Arts and Education | Graduate Student Scholarship at Dominican Scholar. It has been accepted for inclusion in Master of Arts in Humanities | Master's Theses by an authorized administrator of Dominican Scholar. For more information, please contact [email protected]. This thesis, written under the direction of the candidate's thesis advisor and approved by the department chair, has been presented to and accepted by the Master of Arts in Humanities Program in partial fulfillment of the equirr ements for the degree of Master of Arts in Humanities. An electronic copy of of the original signature page is kept on file with the Archbishop Alemany Library. Maura Wilson Candidate Joan Baranow, PhD Program Chair Joan Baranow, PhD First Reader Sandra Chin, MA Second Reader This master's thesis is available at Dominican Scholar: https://scholar.dominican.edu/humanities- masters-theses/6 i The Iconography of the Honey Bee in Western Art By Maura Wilson This thesis, written under the direction of the candidate’s thesis advisor and approved by the program chair, has been presented to an accepted by the Department of Humanities in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Humanities Dominican University of California San Rafael, CA May 2019 ii iii Copyright © Maura Wilson 2019. -

Identifying Bee and Wasp Nests

IDENTIFYING BEE AND WASP NESTS Bumblebees, honey bees, hornets and yellow jackets may look alike from a distance, but their impact on your health, your yard and the ecosystem varies by species. Knowing how to recognize each species’ nest can help identify which of these buzzing insects are making themselves at home in your backyard – and allow for safe removal of any nests on your property. Bumblebees Bumblebees are not overly aggressive and rarely sting STRUCTURE: More disorganized than unless disturbed or threatened. These resourceful bees honey bee nests build nests that typically contain far fewer members than honey bees. MATERIALS USED: Dry grass or plant material surrounded by wax cells LOCATION: Dry, protected and hidden cavities below ground, on or near ground level, such as: Rodent tunnels Structural voids Piles of leaves Abandoned bird nests Honey Bees Although one of the most popular bees, honey bees only STRUCTURE: Impressively large nests represent a small percent of bee species and build nests made of six-sided tubes that to produce and store honey. create honey combs MATERIALS USED: Wax bonded to honey comb cells LOCATION: Areas that scout bees believe are appropriate for their colony, such as: Inside tree cavities Under edges of objects On rock crevices Carpenter Bees STRUCTURE: These excavators feed on plant pollen and nectar and Excavated galleries made up of tunnels with a round, drill are known for their ability to construct nests in wooden hole-size entrance structures. MATERIALS USED: Wood pulp, sticks, twigs LOCATION: Dry, unpainted and weathered wooden objects, particularly: Railings Roof eaves Window sills Doors Decks Fences Hornets When hornets perceive threats near their hives, they become STRUCTURE: Ball-shaped and made of aggressive and can deliver painful stings. -

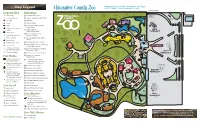

Map Legend 10001 W

Map Legend 10001 W. Bluemound Rd., Milwaukee, WI 53226 414-771-3040 www.milwaukeezoo.org Milwaukee County Zoo Bluemound Rd. Legend Key Buildings Auto teller 8 Animal Health Center Walk-In Entrance Zoofari Change Machine 9 Aquatic & Reptile Center (ARC) Drive-in Exit Animal Health Entrance Conference Center Center First Aid 0 Australia Sea Lion Birds Food - Dairy Complex Show g s Gifts = Dohmen Family Foundation Special Hippo Home Exhibit Handicap/Changing Macaque Island Zebra Station q Family Farm & Public Affairs Office Flamingo Parking Lot Information Swan w Florence Mila Borchert Lost Children’s Area Big Cat Country Fish, an Frogs & angut Mold-a-Rama e Herb & Nada Mahler Family Expedition Snakes Or Primates Apes Aviary Welcome Penny Press Dinosaur Center Summer Gorilla r Holz Family Impala Country 2015 Penguins j Private Picnic Areas ARC Bonobo t Idabel Wilmot Borchert Flamingo Theatre Rest Rooms Siamang Exhibit and Overlook Small Mammals Ropes Courses h Strollers sponsored & y Karen Peck Katz Conservation Zip Line by Wilderness Resort Education Center Giraffe Tornado Shelter u Kohl’s Cares for Kids Play Area Parking Lot i Northwestern Mutual Zoo Rides Family Farm Carousel sponsored African e Briggs o A. Otto Borchert Family Waterhol & Stratton by Penzeys Spices Special Exhibits Building a Zoo ebr Terrace Z Safari Train sponsored B. Jungle Birthday Room Lion by North Shore Bank Cheet Family p Peck Welcome Center Big African Kohl’s Farm Cats Savanna Wild ah Theater Sky Safari sponsored Sky JaguarT [ Primates of the World iger Safari South Live alks by PNC* Prairie America Grizzly Bear Snow Animal T Dairy Elephant ] Small Mammals Building Caribou Dogs Leopard Bongo Barn SkyTrail® Explorer Black Parking Lot Elk Bear Red Hippo Butterfly \ Stackner Animal Encounter Panda Garden Butterfly Ropes Courses & Zip Garden Camel W Line sponsored by a Stearns Family Apes of Africa arthog Bee Pachyderm Hive Exhibit Tri City National Bank* Tapir Pachyderm s Taylor Family Humboldt Penguins d Zoomobile sponsored Education d U.S.