Institution Available from Descriptors

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Download Download

REPORTS 155 The “Local Culture and Diversity on the Prairies” Project (1) Nadya Foty and Andriy Nahachewsky University of Alberta Edmonton, Alberta, Canada Introduction The Peter and Doris Kule Centre for Ukrainian and Canadian Folklore at the University of Alberta is in the process of concluding a project with several partners to record some 900 hours involving 2,000 interviews with people who remember life on the Canadian prairies prior to 1939. The project is called “Local Culture and Diversity on the Prairies” At the time of this writing, most of the interviews have been conducted but the compilation, coding, analysis and description of findings are still underway. For this reason, this essay takes the form of a personal perspective of the project, description of issues influencing project design, and a statement of aspirations rather than an authoritative reporting of its results. The aim of the project has been to document everyday life, ethnic identity and regional variation among people of Ukrainian, French, German and English heritage.(2) How did people from diverse backgrounds interact, adapt and become “prairie Canadians” in the first half of the twentieth century? What was the relationship between cultural inheritance and local community participation? How did they express their various identities on the local community level? What factors affected regional variation in these communities? The project is designed to generate a great deal of documentary information and primary archival resources for further research in many aspects of these people’s lives. Ethnographic research about ethnicity, integration and Canadianiza- tion as social processes in a given period is perhaps best conducted indirectly. -

Acadiens and Cajuns.Indb

canadiana oenipontana 9 Ursula Mathis-Moser, Günter Bischof (dirs.) Acadians and Cajuns. The Politics and Culture of French Minorities in North America Acadiens et Cajuns. Politique et culture de minorités francophones en Amérique du Nord innsbruck university press SERIES canadiana oenipontana 9 iup • innsbruck university press © innsbruck university press, 2009 Universität Innsbruck, Vizerektorat für Forschung 1. Auflage Alle Rechte vorbehalten. Umschlag: Gregor Sailer Umschlagmotiv: Herménégilde Chiasson, “Evangeline Beach, an American Tragedy, peinture no. 3“ Satz: Palli & Palli OEG, Innsbruck Produktion: Fred Steiner, Rinn www.uibk.ac.at/iup ISBN 978-3-902571-93-9 Ursula Mathis-Moser, Günter Bischof (dirs.) Acadians and Cajuns. The Politics and Culture of French Minorities in North America Acadiens et Cajuns. Politique et culture de minorités francophones en Amérique du Nord Contents — Table des matières Introduction Avant-propos ....................................................................................................... 7 Ursula Mathis-Moser – Günter Bischof des matières Table — By Way of an Introduction En guise d’introduction ................................................................................... 23 Contents Herménégilde Chiasson Beatitudes – BéatitudeS ................................................................................................. 23 Maurice Basque, Université de Moncton Acadiens, Cadiens et Cajuns: identités communes ou distinctes? ............................ 27 History and Politics Histoire -

Download Download

European Folktales in Betsiamites Innu LYNN DRAPEAU AND MAGALI LACHAPELLE Université du Québec à Montréal INTRODUCTION1 This paper reports and analyzes tales of French origin gathered among the Innus (a.k.a. Montagnais) of Betsiamites in Quebec. Since anthropologists have mainly focused on Native tales told by the Innus, the widespread exis- tence of European tales in their repertoire was never fully acknowledged. As this paper will show, in Betsiamites at least, tales of European origin were widespread and fully integrated into the Native inventory. Nine different tales recorded in this community are analyzed for the purpose of this study and compared to their corresponding types in the latest index of world folk- lore (Uther 2004). The most striking feature is their adaptation to the Native cultural context. A detailed analysis of their sequences of events reveals how the tales were repackaged and reinterpreted with Indigenous heroes living alongside protagonists of European origin. We show how a subgroup of Innus settled along the St. Lawrence coast in the eighteenth century, called the Innus of the sea, are most probably responsible for the adoption and dissemination of those tales into the Betsiamites Innus’ repertoire. FRENCH TALES IN NORTH AMERICAN INDIGENOUS GROUPS This brief section cannot do justice to the wealth of data on European tales in North American Indigenous groups. For the purpose of the present study, we will restrict our overview to those which are most relevant to our study, namely tales of French origin with a focus on Algonquian groups. 1. Many thanks to José Mailhot as well as to two anonymous reviewers for helpful comments and suggestions. -

Canadian and Russian Animation on Northern Aboriginal Folklore

Canadian and Russian Animation on Northern Aboriginal Folklore Elena Korniakova A Thesis in The Individualized Program of The School of Graduate Studies Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts (Fine Arts) at Concordia University Montreal, Quebec, Canada September 2014 Elena Korniakova, 2014 CONCORDIA UNIVERSITY School of Graduate Studies This is to certify that the thesis prepared By: Elena Korniakova Entitled: Canadian and Russian Animation on Northern Aboriginal Folklore and submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirement for the degree of Master of Arts (Fine Arts) complies with the regulations of the University and meets the accepted standards with respect to originality and quality. Signed by the final Examining Committee: _________________________________Chair Chair's name _________________________________Examiner Examiner's name _________________________________Examiner Examiner's name _________________________________Supervisor Supervisor's name Approved by ______________________________________________________ Chair of Department or Graduate Program Director _____________2014 ____________________________________________________ Dean of Faculty -iii- ABSTRACT Canadian and Russian Animation on Northern Aboriginal Folklore Elena Korniakova Aboriginal legends depict the relationships between humans and nature as deeply symbolic and intertwined. When adapted to films by non-Aboriginal filmmakers, these legends are often interpreted in ways which modify human-nature relationships experienced by Aboriginal peoples. I explore such modifications by looking at Canadian and Russian ethnographic animation based on Northern Aboriginal folklore of the two countries. In my thesis, I concentrate on the analysis of ethno-historical and cinematic traditions of Canada and Russia. I also explore the Canadian and Russian conventions of animated folktales and compare ethnographic animation produced by the National Film Board of Canada and Russian animation studio Soyuzmultfilm. -

From the on Inal Document. What Can I Write About?

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 470 655 CS 511 615 TITLE What Can I Write about? 7,000 Topics for High School Students. Second Edition, Revised and Updated. INSTITUTION National Council of Teachers of English, Urbana, IL. ISBN ISBN-0-8141-5654-1 PUB DATE 2002-00-00 NOTE 153p.; Based on the original edition by David Powell (ED 204 814). AVAILABLE FROM National Council of Teachers of English, 1111 W. Kenyon Road, Urbana, IL 61801-1096 (Stock no. 56541-1659: $17.95, members; $23.95, nonmembers). Tel: 800-369-6283 (Toll Free); Web site: http://www.ncte.org. PUB TYPE Books (010) Guides Classroom Learner (051) Guides Classroom Teacher (052) EDRS PRICE EDRS Price MF01/PC07 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS High Schools; *Writing (Composition); Writing Assignments; *Writing Instruction; *Writing Strategies IDENTIFIERS Genre Approach; *Writing Topics ABSTRACT Substantially updated for today's world, this second edition offers chapters on 12 different categories of writing, each of which is briefly introduced with a definition, notes on appropriate writing strategies, and suggestions for using the book to locate topics. Types of writing covered include description, comparison/contrast, process, narrative, classification/division, cause-and-effect writing, exposition, argumentation, definition, research-and-report writing, creative writing, and critical writing. Ideas in the book range from the profound to the everyday to the topical--e.g., describe a terrible beauty; write a narrative about the ultimate eccentric; classify kinds of body alterations. With hundreds of new topics, the book is intended to be a resource for teachers and students alike. (NKA) Reproductions supplied by EDRS are the best that can be made from the on inal document. -

Compound Diction and Traditional Style in Beowulf and Genesis A

Oral Tradition, 6/1 (1991): 79-92 Compound Diction and Traditional Style in Beowulf and Genesis A Jeffrey Alan Mazo One of the most striking features of Anglo-Saxon alliterative poetry is the extraordinary richness of the vocabulary. Many words appear only in poetry; almost every poem contains words, usually nominal or adjectival compounds, which occur nowhere else in the extant literature. Creativity in coining new compounds reaches its apex in the 3182-line heroic epic Beowulf. In his infl uential work The Art of Beowulf, Arthur G. Brodeur sets out the most widely accepted view of the diction of that poem (1959:28): First, the proportion of such compounds in Beowulf is very much higher than that in any other extant poem; and, secondly, the number and the richness of the compounds found in Beowulf and nowhere else is astonishingly large. It seems reasonable, therefore, to regard the many unique compounds in Beowulf, fi nely formed and aptly used, as formed on traditional patterns but not themselves part of a traditional vocabulary. And to say that they are formed on traditional patterns means only that the character of the language spoken by the poet and his hearers, and the traditional tendency towards poetic idealization, determined their character and form. Their elevation, and their harmony with the poet’s thought and feeling, refl ect that tendency, directed and controlled by the genius of a great poet. It goes without saying that the poet of Beowulf was no “unwashed illiterate,” but a highly trained literary artist who could transcend the traditional medium. -

Courier Gazette

Issued Thursday ■Rjesd/w Thursday Issue Saturday The Couri Gazette Established January, 1846. Entered as Second Class Mat) Matter THREE CENTS A COPY Volume 92.................. Number 1 20. By The Courier-Gazette, 465 Main St. Rockland, Maine, Thursday, October 7, 1937 The Courier-Gazette STRICTLY ENFORCED THREE-TIMES-A-WEEK Will Be the State's Packing law, MAKE PLANS FOR BUSY WINTER COME FROM MANY STATES THE ROCKLAND LIONS Editor According to Com'r. Washburn WM. O. FULLER Associate Editor With the advent of Maine’s appIe Community Building Will Soon Be Up and Doing The National Council Of Garden Clubs Opened A Popular Speaker Tells Them How He Spent FRANK A WINSLOW picking season. Commissioner Wash- ^U.bn«;,PXT*. Z-TOT 1D burn of the Department of Agricul- —Chamber Of Commerce Invited Sessions At Camden This Morning His Summer Vacation t»oAn «d ven JeTon^r UP°D | lure Tuesday, notified apple grow- Ths RoS^Stu^Jtab.Uh.d,^ ”ackerS and shlpp*» that th« Under Sharp mandate of the Board the building plans were in the making A welcoming hand is being ex rapid succession as indicated by the The Rockland Lions indulged in a with their lot. Laborers receive $2 a In 1846 In 1874 the Courier was estab- 1 state's nackine law would be day or $40 a month. Quebec has an llahed and consolidated with the Gazette p 8 of Control of Community Building to |that th« alle>' and spectator gal- tended today to garden devotees hail full program here presented: bit of (horse play at the expense of ln 1882. -

Oral Tradition

_____________________________________________________________ Volume 6 January 1991 Number 1 _____________________________________________________________ Editor Editorial Assistants John Miles Foley Sarah J. Feeny David Henderson Managing Editor Whitney Strait Lee Edgar Tyler J. Chris Womack Book Review Editor Adam Brooke Davis Slavica Publishers, Inc. Slavica Publishers, Inc. For a complete catalog of books from Slavica, with prices and ordering information, write to: Slavica Publishers, Inc. P.O. Box 14388 Columbus, Ohio 43214 ISSN: 0883-5365 Each contribution copyright (c) 1991 by its author. All rights reserved. The editor and the publisher assume no responsibility for statements of fact or opinion by the authors. Oral Tradition seeks to provide a comparative and interdisciplinary focus for studies in oral literature and related fields by publishing research and scholarship on the creation, transmission, and interpretation of all forms of oral traditional expression. As well as essays treating certifiably oral traditions, OT presents investigations of the relationships between oral and written traditions, as well as brief accounts of important fieldwork, a Symposium section (in which scholars may reply at some length to prior essays), review articles, occasional transcriptions and translations of oral texts, a digest of work in progress, and a regular column for notices of conferences and other matters of interest. In addition, occasional issues will include an ongoing annotated bibliography of relevant research and the annual Albert Lord and Milman Parry Lectures on Oral Tradition. OT welcomes contributions on all oral literatures, on all literatures directly influenced by oral traditions, and on non-literary oral traditions. Submissions must follow the list-of reference format (style sheet available on request) and must be accompanied by a stamped, self-addressed envelope for return or for mailing of proofs; all quotations of primary materials must be made in the original language(s) with following English translations. -

Cr2016-Program.Pdf

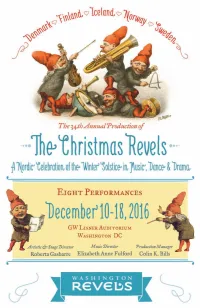

l Artistic Director’s Note l Welcome to one of our warmest and most popular Christmas Revels, celebrating traditional material from the five Nordic countries: Denmark, Finland, Iceland, Norway, and Sweden. We cannot wait to introduce you to our little secretive tomtenisse; to the rollicking and intri- cate traditional dances, the exquisitely mesmerizing hardingfele, nyckelharpa, and kantele; to Ilmatar, heaven’s daughter; to wild Louhi, staunch old Väinämöinen, and dashing Ilmarinen. This “journey to the Northlands” beautifully expresses the beating heart of a folk community gathering to share its music, story, dance, and tradition in the deep midwinter darkness. It is interesting that a Christmas Revels can feel both familiar and entirely fresh. Washing- ton Revels has created the Nordic-themed show twice before. The 1996 version was the first show I had the pleasure to direct. It was truly a “folk” show, featuring a community of people from the Northlands meeting together in an annual celebration. In 2005, using much of the same script and material, we married the epic elements of the story with the beauty and mystery of the natural world. The stealing of the sun and moon by witch queen Louhi became a rich metaphor for the waning of the year and our hope for the return of warmth and light. To create this newest telling of our Nordic story, especially in this season when we deeply need the circle of community to bolster us in the darkness, we come back to the town square at a crossroads where families meet at the holiday to sing the old songs, tell the old stories, and step the circling dances to the intricate stringed fiddles. -

Beowulf As Epic

Oral Tradition, 15/1 (2000): 159-169 Beowulf as Epic Joseph Harris Cambridge, Massachusetts, has been home to two translators of the Kalevala in the twentieth century, and both furnished materials, however brief, for an understanding of how they might have compared the Finnish epic to the Anglo-Saxon Beowulf. (The present brief Canterbridgean contribution to the generic characterization of Beowulf, taking a hint from the heterogeneous genre make-up of the Kalevala, focuses chiefly on a complex narrative structure and its meaning.) The better known of the two translators was my distinguished predecessor, the English professor and philologist Francis Peabody Magoun (1895-1979). In his 1963 translation of the 1849 Kalevala, Magoun’s allusions, still strongly under the spell of the early successes of the oral-formulaic theory, are chiefly to shared reliance on formulaic diction, though he does also point out certain differences in the two epics’ application of this style (1963a:xvii, n. 1; xviii, n. 3). Magoun’s reference to “the Beowulf songs” (xviii, n. 3) in the plural, however, alludes to his belief that different folk variants on the life of the hero can still be discriminated in the epic. By the time of his 1969 translation of the Old Kalevala Magoun seems not too far from the current standard view (xiv): . such a semi-connected, semi-cyclic work as the Kalevala or the received text of the Anglo-Saxon Béowulf, however oral in its genesis, cannot possibly be the product of oral composition. Unlettered singers create in response to an immediate, eagerly waiting audience; they do not compose cyclically, but episodically . -

Wisconsin Folklore and Folklife Society Which Has Excellent Promise

FOLKLORE Walker D. Wyman Acknowledgement Unive rsity of Wisconsin-Extension· is especially indebted to Dr. Loren Robin son of the Department of J ournali sm, University of Wisconsin, River Fall s, and lo Leon Zaborowski, Universit y Extension, River Falls, for the initial concept of a series of articles on Wisconsin fo lklore, published through daily and weekly newspa pe rs in Wisconsin. It was from those articles by Walker Wyman that this book was developed. The contribution of the va rious newspapers which ca rried the articles is also gratefully acknowledged. A Grass Roots Book Copyright © 1979 by Unive r sity of Wisconsin Boar d of Regents All r ight s r eserved Libra ry of Congress Catalog Ca rd Number 79-65323 Published by University of Wisconsin-Extension Department of Arts Development. Price: $4.95 ii Foreword The preparation of a book on folklore to be published by the University Exten sion is a major event. There has been, for many years, strong sentiment that the University of Wisconsi n ought to take a more dynamic interest in folklore, and that eventually, academic work in that subject should be established on many of the cam puses. So far only the Universities at Eau C laire, River Falls, and at Stevens Point have formal courses. The University at M adison has never had an y such course though informal interest has been strongly present. The University at R iver Falls has developed, through the activities and interests of Dr. Walker W yman, a publish ing program which has produced several books of regional fol klore. -

American Studies Through Folktales. PUB DATE 92 NOTE 24P.; Journal Article Offprint

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 393 765 SO 026 134 AUTHOR Pedersen, E. Martin TITLE American Studies through Folktales. PUB DATE 92 NOTE 24p.; Journal article offprint. PUB TYPE Journal Articles (080) JOURNAL CIT Messana: Rassegna Di Studi Filologici Linguistici E Storici; nll p165-185 1992 EDRS PRICE MF01/PC01 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS *American Studies; *Folk Culture; Higher Education; United States History IDENTIFIERS *Folktales; Steinbeck (John); Twain (Mark) ABSTRACT American studies is a combination of fields such as literature, history, phinsophy, politics, and economics. This publication examines how tie different fields of study relate to American studies through folklore or folktales. The use of folktales can provide better illust-ations and understandings of U.S. individuals' heritage and evolution. Famous artists noted for using folktales to describe U.S. culture are Mark Twain and John Steinbeck. (JAG) *********************************************************************** Reproductions supplied by EDRS are the best that can be made from the original document. *********************************************************************** "PERMISSION TO REPRODUCE THIS MATERIAL HAS BEEN GRANTED BY U.S. DEPARTMENT OF EDUCATION Office ol Educational Research and improvement EDUCATIONAL RESOURCES INFORMATION CENTER (ERIC) This document has been reproduced as received from the person or organization TO THE EDUCATIONAL RESOURCES originating it. INFORMATION CENTER (ERIC)." Qs Minor changes have been made to -----------improve reproduction quality. 0 Points of view or opinions staled in this document do not necessarily represent official OERI position or policy. VJ BEST COPY AVAILABLE % AMERICAN STUDIES THROUGH FOLK TALES' Folklore and American studies The basic social sciences, the language arts, and the fine and prac- tical arts all have aspects of similarity, and there is some overlapping among them.