Oral Tradition

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sećanje Na Paju Jovanovića I Konstantina Babića: Katalog

УНИВЕРЗИТЕТ У НИШУ ФАКУЛТЕТ УМЕТНОСТИ У НИШУ Весна Гагић Сећање на Пају јовановића и Константина Бабића: каталог биографске изложбе и библиографија радова НИШ, 2020. Весна Гагић Vesna Gagić СEЋAЊE НA ПAJУ JOВAНOВИЋA И КOНСТAНТИНA БAБИЋA: IN REMEMBRANCE OF PAJA JOVANOVIĆ AND KONSTANTIN КAТAЛOГ БИOГРAФСКE ИЗЛOЖБE И БИБЛИOГРAФИJA BABIĆ: THE BIOGRAPHICAL EXHIBITION CATALOGUE AND РAДOВA THE BIBLIOGRAPHY OF WORKS Прво издање, Ниш, 2020. First edition, Niš, 2020.. Рецензенти Reviewers мр Перица Донков, ред. проф. Факултета уметности Универзитета у Нишу Perica Donkov, MA, Full professor at the Faculty of Arts, University of Niš др Jeлeнa Цвeткoвић Црвeницa, ванр. проф. Факултета уметности Jelena Cvetković Crvenica, PhD, Associate professor at the Faculty of Arts, University Универзитета у Нишу of Niš др Tатјана Брзуловић Станисављевић, библиотекар саветник Универзитетске Tatjana Brzulović Stanisavljević, PhD, Librarian-consultant of the University Library библиотеке „Светозар Марковић”, Београд Svetozar Marković, Belgrade Рецензенти из области музике за приложени стручни рад Reviewers in the field of music for the attached professional works др Наташа Нагорни Петров, ванр. проф. Факултета уметности Универзитета Nataša Nagorni Petrov, PhD, Associate professor at the Faculty of Arts, у Нишу University of Nis мр Марко Миленковић, доцент Факултета уметности Универзитета у Нишу Marko Milenković, MA, Assistant Professor at the Faculty of Arts, University of Niš Издавач Publisher УНИВЕРЗИТЕТ У НИШУ УНИВЕРЗИТЕТ У НИШУ ФАКУЛТЕТ УМЕТНОСТИ У НИШУ ФАКУЛТЕТ -

The Challenge of Oral Epic to Homeric Scholarship

humanities Article The Challenge of Oral Epic to Homeric Scholarship Minna Skafte Jensen The Saxo Institute, Copenhagen University, Karen Blixens Plads 8, DK-2300 Copenhagen S, Denmark; [email protected] or [email protected] Received: 16 November 2017; Accepted: 5 December 2017; Published: 9 December 2017 Abstract: The epic is an intriguing genre, claiming its place in both oral and written systems. Ever since the beginning of folklore studies epic has been in the centre of interest, and monumental attempts at describing its characteristics have been made, in which oral literature was understood mainly as a primitive stage leading up to written literature. With the appearance in 1960 of A. B. Lord’s The Singer of Tales and the introduction of the oral-formulaic theory, the paradigm changed towards considering oral literature a special form of verbal art with its own rules. Fieldworkers have been eagerly studying oral epics all over the world. The growth of material caused that the problems of defining the genre also grew. However, after more than half a century of intensive implementation of the theory an internationally valid sociological model of oral epic is by now established and must be respected in cognate fields such as Homeric scholarship. Here the theory is both a help for readers to guard themselves against anachronistic interpretations and a necessary tool for constructing a social-historic context for the Iliad and the Odyssey. As an example, the hypothesis of a gradual crystallization of these two epics is discussed and rejected. Keywords: epic; genre discussion; oral-formulaic theory; fieldwork; comparative models; Homer 1. -

(1389) and the Munich Agreement (1938) As Political Myths

Department of Political and Economic Studies Faculty of Social Sciences University of Helsinki The Battle Backwards A Comparative Study of the Battle of Kosovo Polje (1389) and the Munich Agreement (1938) as Political Myths Brendan Humphreys ACADEMIC DISSERTATION To be presented, with the permission of the Faculty of Social Sciences of the University of Helsinki, for public examination in hall XII, University main building, Fabianinkatu 33, on 13 December 2013, at noon. Helsinki 2013 Publications of the Department of Political and Economic Studies 12 (2013) Political History © Brendan Humphreys Cover: Riikka Hyypiä Distribution and Sales: Unigrafia Bookstore http://kirjakauppa.unigrafia.fi/ [email protected] PL 4 (Vuorikatu 3 A) 00014 Helsingin yliopisto ISSN-L 2243-3635 ISSN 2243-3635 (Print) ISSN 2243-3643 (Online) ISBN 978-952-10-9084-4 (paperback) ISBN 978-952-10-9085-1 (PDF) Unigrafia, Helsinki 2013 We continue the battle We continue it backwards Vasko Popa, Worriors of the Field of the Blackbird A whole volume could well be written on the myths of modern man, on the mythologies camouflaged in the plays that he enjoys, in the books that he reads. The cinema, that “dream factory” takes over and employs countless mythical motifs – the fight between hero and monster, initiatory combats and ordeals, paradigmatic figures and images (the maiden, the hero, the paradisiacal landscape, hell and do on). Even reading includes a mythological function, only because it replaces the recitation of myths in archaic societies and the oral literature that still lives in the rural communities of Europe, but particularly because, through reading, the modern man succeeds in obtaining an ‘escape from time’ comparable to the ‘emergence from time’ effected by myths. -

Műfordítás És Kulturális Identitás Az Új Symposion Folyóiratban1

partitura-2019-1_partitura-2010-1.qxd 2019. 11. 19. 13:43 page 65 Ladányi István Műfordítás és kulturális identitás az Új Symposion folyóiratban1 Absztrakt: a magyar nyelven megjelent, újvidéki kiadású Új symposion folyóirat erő- teljes jugoszláviai kulturális beágyazottsága ismert, ugyanakkor nem magától értetődő sajátossága a vajdasági magyar irodalomnak. a témában számos részkutatás folyt mind a folyóirattal, mind az egyes fontosabb szerzőivel, szerkesztőivel kapcsolatban. a jelen tanulmány egy folyamatban lévő kutatás eddigi eredményeiről számol be, a folyó- irat fordítási gyakorlatát állítva középpontba, összefüggésben a folyóiratnak a délszláv irodalmakra vonatkozó reflexív szövegeivel. a délszláv nyelvekből történő fordítások nem idegen kulturális közegek közötti transzferként jelentkeznek, és jellemzően nem olyan olvasóknak készülnek, akik az eredeti művet nem tudnák elolvasni. a folyóirat dinamikus regionális kulturális identitásalakzatokat mutatott fel a saját lokális kisebbsé- gi kultúrával, az egyetemes magyar kultúrával és a jugoszlávnak nevezett kultúrával kapcsolatban. a valamelyikkel való teljes és kizárólagos azonosulás helyett a participá- ció alakzatait láthatjuk. 65 a vajdasági magyar irodalommal, illetve a jugoszláviai magyar irodalommal foglalkozó magyar irodalomtörténet-írás alapvető megállapítása az újvidéki Új Symposion folyóirattal kapcsolatban annak jugoszláviai kulturális beágyazott- sága. a témát tárgyaló megközelítéstől függően az egyes szerzőknél ez a beá- gyazottság példa lehet egy sajátos regionális identitás -

Compound Diction and Traditional Style in Beowulf and Genesis A

Oral Tradition, 6/1 (1991): 79-92 Compound Diction and Traditional Style in Beowulf and Genesis A Jeffrey Alan Mazo One of the most striking features of Anglo-Saxon alliterative poetry is the extraordinary richness of the vocabulary. Many words appear only in poetry; almost every poem contains words, usually nominal or adjectival compounds, which occur nowhere else in the extant literature. Creativity in coining new compounds reaches its apex in the 3182-line heroic epic Beowulf. In his infl uential work The Art of Beowulf, Arthur G. Brodeur sets out the most widely accepted view of the diction of that poem (1959:28): First, the proportion of such compounds in Beowulf is very much higher than that in any other extant poem; and, secondly, the number and the richness of the compounds found in Beowulf and nowhere else is astonishingly large. It seems reasonable, therefore, to regard the many unique compounds in Beowulf, fi nely formed and aptly used, as formed on traditional patterns but not themselves part of a traditional vocabulary. And to say that they are formed on traditional patterns means only that the character of the language spoken by the poet and his hearers, and the traditional tendency towards poetic idealization, determined their character and form. Their elevation, and their harmony with the poet’s thought and feeling, refl ect that tendency, directed and controlled by the genius of a great poet. It goes without saying that the poet of Beowulf was no “unwashed illiterate,” but a highly trained literary artist who could transcend the traditional medium. -

Cr2016-Program.Pdf

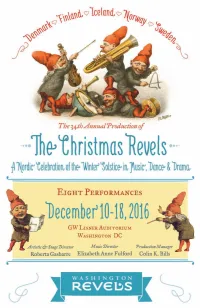

l Artistic Director’s Note l Welcome to one of our warmest and most popular Christmas Revels, celebrating traditional material from the five Nordic countries: Denmark, Finland, Iceland, Norway, and Sweden. We cannot wait to introduce you to our little secretive tomtenisse; to the rollicking and intri- cate traditional dances, the exquisitely mesmerizing hardingfele, nyckelharpa, and kantele; to Ilmatar, heaven’s daughter; to wild Louhi, staunch old Väinämöinen, and dashing Ilmarinen. This “journey to the Northlands” beautifully expresses the beating heart of a folk community gathering to share its music, story, dance, and tradition in the deep midwinter darkness. It is interesting that a Christmas Revels can feel both familiar and entirely fresh. Washing- ton Revels has created the Nordic-themed show twice before. The 1996 version was the first show I had the pleasure to direct. It was truly a “folk” show, featuring a community of people from the Northlands meeting together in an annual celebration. In 2005, using much of the same script and material, we married the epic elements of the story with the beauty and mystery of the natural world. The stealing of the sun and moon by witch queen Louhi became a rich metaphor for the waning of the year and our hope for the return of warmth and light. To create this newest telling of our Nordic story, especially in this season when we deeply need the circle of community to bolster us in the darkness, we come back to the town square at a crossroads where families meet at the holiday to sing the old songs, tell the old stories, and step the circling dances to the intricate stringed fiddles. -

The Dynamics of German Translations of Texts by Contemporary Authors from Tito’S Yugoslavia

The Dynamics of German Translations of Texts THE DYNAMICS OF GERMAN TRANSLATIONS OF TEXTS BY CONTEMPORARY AUTHORS FROM TITO’S YUGOSLAVIA Gertraud Marinelli-König Österreichische Akademie der Wissenschaften Abstract. The subject of this paper is the book market in the four German speaking coun- tries (FRG, Occ. Germany, Switzerland and Austria) during the period of Tito’s Yugosla- via (1945–1980) based on the bibliography Serbo-Croatian writers in German translation (1776–1993) by Reinhard Lauer (1995). In chronological order the titles of books by contem- porary writers translated from Serbo-Croatian into German are listed whereby the focus is directed to publishers. The label “Serbo-Croatian” as the name of the language spoken and written by several ethnic communities in former Yugoslavia as the source language from which the books were translated into the target language German has become a contested label ever since. The national affiliation of the respective author of a book overruled the aspect of adher- ence to a common language. The disentanglement of this literary cosmos has been at stake ever since the collapse of Yugoslavia; the label “Serbo-Croatian writer” has become obsolete. Keywords: Serbo-Croatian writers in German translation 1945–1980; book mar- ket in the four German speaking countries (FRG, Occ. Germany, Switzerland and Austria); list of titles; focus on publishers. INTRODUCTION Literary texts in translation are most visible as books published in the countries where the target language is spoken. This was the case in four countries during the Tito era: publishing houses in the German Democratic Republic (DDR), the Federal Republic of Germany (BRD), Switzerland (CH), and Austria (A) would include translations whose source language was then called Serbo-Croatian. -

Beowulf As Epic

Oral Tradition, 15/1 (2000): 159-169 Beowulf as Epic Joseph Harris Cambridge, Massachusetts, has been home to two translators of the Kalevala in the twentieth century, and both furnished materials, however brief, for an understanding of how they might have compared the Finnish epic to the Anglo-Saxon Beowulf. (The present brief Canterbridgean contribution to the generic characterization of Beowulf, taking a hint from the heterogeneous genre make-up of the Kalevala, focuses chiefly on a complex narrative structure and its meaning.) The better known of the two translators was my distinguished predecessor, the English professor and philologist Francis Peabody Magoun (1895-1979). In his 1963 translation of the 1849 Kalevala, Magoun’s allusions, still strongly under the spell of the early successes of the oral-formulaic theory, are chiefly to shared reliance on formulaic diction, though he does also point out certain differences in the two epics’ application of this style (1963a:xvii, n. 1; xviii, n. 3). Magoun’s reference to “the Beowulf songs” (xviii, n. 3) in the plural, however, alludes to his belief that different folk variants on the life of the hero can still be discriminated in the epic. By the time of his 1969 translation of the Old Kalevala Magoun seems not too far from the current standard view (xiv): . such a semi-connected, semi-cyclic work as the Kalevala or the received text of the Anglo-Saxon Béowulf, however oral in its genesis, cannot possibly be the product of oral composition. Unlettered singers create in response to an immediate, eagerly waiting audience; they do not compose cyclically, but episodically . -

Annotated Bibliography of Works by John Miles Foley

This article belongs to a special issue of Oral Tradition published in honor of John Miles Foley’s 65th birthday and 2011 retirement. The surprise Festschrift, guest-edited by Lori and Scott Garner entirely without his knowledge, celebrates John’s tremendous impact on studies in oral tradition through a series of essays contributed by his students from the University of Missouri- Columbia (1979-present) and from NEH Summer Seminars that he has directed (1987-1996). http://journal.oraltradition.org/issues/26ii This page is intentionally left blank. Oral Tradition, 26/2 (2011): 677-724 Annotated Bibliography of Works by John Miles Foley Compiled by R. Scott Garner In 1985 John Miles Foley authored as his first book-length work Oral-Formulaic Theory and Research: An Introduction and Annotated Bibliography. This volume, which provided an introduction to the field of study and over 1800 annotated entries, was later supplemented by updates published in Oral Tradition (and compiled by John himself, Lee Edgar Tyler, Juris Dilevko, and Catherine S. Quick [with the assistance of Patrick Gonder, Sarah Feeny, Amerina Engel, Sheril Hook, and Rosalinda Villalobos Lopez]) that served both to summarize and to provide reflection upon new developments in an area of scholarship that eventually became too vast and broadly evolved to be contained by any single bibliographic venture. Given that John’s own work was instrumental in effecting this sustained development—while also having importance in so many other areas of study as well—it seems only fitting to close the current volume with an annotated bibliography of John’s works up through the current point in time. -

Textual Community and Linguistic Distance in Early England

Textual Community and Linguistic Distance in Early England by Emily Elisabeth Butler A thesis submitted in conformity with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Centre for Medieval Studies University of Toronto © Copyright by Emily Elisabeth Butler 2010 Textual Community and Linguistic Distance in Early England Emily Elisabeth Butler Doctor of Philosophy Centre for Medieval Studies University of Toronto 2010 Abstract This dissertation examines the function of textual communities in England from the early Middle Ages until the early modern period, exploring the ways in which cultures and communities are formed through textual activities other than writing itself. I open by discussing the characteristics of a textual community in order to establish a new understanding of the term. I argue that a textual community is fundamentally based on activity carried out in books and that perceptions of linguistic distance stimulate this activity. Chapter 1 investigates Bede (c. 673–735) and his interest in multilingualism, coupled with his exploration of the boundaries between the written and spoken forms of English. Picking up on an element of Bede‘s work, I argue in Chapter 2 that Alfred (r. 871–899) and his grandson Æthelstan (r. 924/5–939) found new ways to make textuality the defining quality of the emerging West Saxon kingdom. In Chapter 3, I focus on the intralingual distance in the textual community surrounding the works of Ælfric (c. 950–1010) and Wulfstan (d. 1023). I also discuss the role of contemporary or near- contemporary manuscript use in forming a textual community at the intersection of ecclesiastical and political power. -

Charles A. Owen, Jr. Medieval Studies Library Catalog (Update in Progress)

Charles A. Owen, Jr. Medieval Studies Library Catalog (Update in Progress) AC 1 E8 1976 Chretien De Troyes. Arthurian Romances. Trans. W.W. Comfort. London: J.M. Dent & Sons, 1976. AC 1 E8 1978 Chretien De Troyes. Arthurian Romances. Trans. W.W. Comfort. London: J.M. Dent & Sons, 1978. AC 1 E8 D3 Dasent, George Webbe, trans. The Story of Burnt Njal. London: Dent, 1949. AC 1 E8 G6 Gordon, R.K., trans. Anglo-Saxon Poetry. London: Dent, 1936. AC 1 G72 St. Augustine. Confessions. Trans. R.S. Pine-Coffin. New York: Penguin,1978. AC 5 V3 v.2 Essays in Honor of Walter Clyde Curry. Vol. 2. Nashville: Vanderbilt UP, 1954. AC 8 B79 Bryce, James. University and Historical Addresses. London: Macmillan, 1913. AC 15 C55 Brannan, P.T., ed. Classica Et Iberica: A Festschrift in Honor of The Reverend Joseph M.-F. Marique. Worcester, MA: Institute for Early Christian Iberian Studies, 1975. AE 2 B3 Anglicus, Bartholomew. Medieval Lore: An Epitome of the Science, Geography, Animal and Plant Folk-lore and Myth of the Middle Age. Ed. Robert Steele. London: Elliot Stock, 1893. AE 2 H83 Hugh of St. Victor. The Didascalion. Trans. Jerome Taylor. New York: Columbia UP, 1991. 2 copies. AE 2 I8313 Lindsay, W.M., ed. Isidori Hispalensis Episcopi: Etymologiarum Sive Originum. Libri I-X. Scriptorum Classicorum Bibliotheca Oxoniensis. London: Oxford UP, 1966. AE 2 I8313 Lindsay, W.M., ed. Isidori Hispalensis Episcopi: Etymologiarum Sive Originum. Libri XI-XX. Scriptorum Classicorum Bibliotheca Oxoniensis. London: Oxford UP, 1966. AS 122 L5 v.32 Edwards, J. Goronwy. -

Download File

Eastern European Modernism: Works on Paper at the Columbia University Libraries and The Cornell University Library Compiled by Robert H. Davis Columbia University Libraries and Cornell University Library With a Foreword by Steven Mansbach University of Maryland, College Park With an Introduction by Irina Denischenko Georgetown University New York 2021 Cover Illustration: No. 266. Dvacáté století co dalo lidstvu. Výsledky práce lidstva XX. Věku. (Praha, 1931-1934). Part 5: Prokroky průmyslu. Photomontage wrappers by Vojtěch Tittelbach. To John and Katya, for their love and ever-patient indulgence of their quirky old Dad. Foreword ©Steven A. Mansbach Compiler’s Introduction ©Robert H. Davis Introduction ©Irina Denischenko Checklist ©Robert H. Davis Published in Academic Commons, January 2021 Photography credits: Avery Classics Library: p. vi (no. 900), p. xxxvi (no. 1031). Columbia University Libraries, Preservation Reformatting: Cover (No. 266), p.xiii (no. 430), p. xiv (no. 299, 711), p. xvi (no. 1020), p. xxvi (no. 1047), p. xxvii (no. 1060), p. xxix (no. 679), p. xxxiv (no. 605), p. xxxvi (no. 118), p. xxxix (nos. 600, 616). Cornell Division of Rare Books & Manuscripts: p. xv (no. 1069), p. xxvii (no. 718), p. xxxii (no. 619), p. xxxvii (nos. 803, 721), p. xl (nos. 210, 221), p. xli (no. 203). Compiler: p. vi (nos. 1009, 975), p. x, p. xiii (nos. 573, 773, 829, 985), p. xiv (nos. 103, 392, 470, 911), p. xv (nos. 1021, 1087), p. xvi (nos. 960, 964), p. xix (no. 615), p. xx (no. 733), p. xxviii (no. 108, 1060). F.A. Bernett Rare Books: p. xii (nos. 5, 28, 82), p.