Tall Tale Activities

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Courier Gazette

Issued Thursday ■Rjesd/w Thursday Issue Saturday The Couri Gazette Established January, 1846. Entered as Second Class Mat) Matter THREE CENTS A COPY Volume 92.................. Number 1 20. By The Courier-Gazette, 465 Main St. Rockland, Maine, Thursday, October 7, 1937 The Courier-Gazette STRICTLY ENFORCED THREE-TIMES-A-WEEK Will Be the State's Packing law, MAKE PLANS FOR BUSY WINTER COME FROM MANY STATES THE ROCKLAND LIONS Editor According to Com'r. Washburn WM. O. FULLER Associate Editor With the advent of Maine’s appIe Community Building Will Soon Be Up and Doing The National Council Of Garden Clubs Opened A Popular Speaker Tells Them How He Spent FRANK A WINSLOW picking season. Commissioner Wash- ^U.bn«;,PXT*. Z-TOT 1D burn of the Department of Agricul- —Chamber Of Commerce Invited Sessions At Camden This Morning His Summer Vacation t»oAn «d ven JeTon^r UP°D | lure Tuesday, notified apple grow- Ths RoS^Stu^Jtab.Uh.d,^ ”ackerS and shlpp*» that th« Under Sharp mandate of the Board the building plans were in the making A welcoming hand is being ex rapid succession as indicated by the The Rockland Lions indulged in a with their lot. Laborers receive $2 a In 1846 In 1874 the Courier was estab- 1 state's nackine law would be day or $40 a month. Quebec has an llahed and consolidated with the Gazette p 8 of Control of Community Building to |that th« alle>' and spectator gal- tended today to garden devotees hail full program here presented: bit of (horse play at the expense of ln 1882. -

Institution Available from Descriptors

DOCUMENT RES UME ED 070 045 CS 000 230 AUTHOR Carlson, Ruth Kearney, Comp. TITLE Folklore and Folktales Around the world. Perspectives in Reading No. 15. INSTITUTION International Reading Association, Newark, Del., PUB DATE 72 NOTE 179p.; Papers presented at the International Reading Association'sAnnual Convention (15th, Anaheim, Calif., 1970) AVAILABLE FROMInternationalReading Association, Six Tyre Avenue, Newark, Del.19711 ($4.50 non-member, $3.50 member) EDRS PRICE MF-$0.65 HC-$6.58 DESCRIPTORS *Booklists; Fables; *Folklore Books; Legends; Literature Appreciation; Mythology; Reading Materials; *Reading Material Selection; *world Literature IDENTIFIERS *Folktales ABSTRACT This volume, the third in the International Reading Association's Perspectives Series on literature for school age children, concerns the role of folklore and the types of folktales in several areas of the world. These papers were originally presented at IRA's Fifteenth Annual Convention held in Anaheim, California, in 1970. Several articles are devoted to folktales of the western hemisphere and those of Europe. One essay concerns the world folktale, and another the folktales of the Pacific area. An extensive bibliography of folklore and folktales completes the book. (Author/TO) U.S. DEPARTMENT OF HEALTH. EDUCATION & WELFARE OFFICE OF EDUCATION THIS DOCUMENT HAS BEEN REPRO. DUCED EXACTLY AS RECEIVED FROM THE PERSON OR ORGANIZATION ORIG. INATING IT POINTS OF VIEW OR OPIN IONS ST ATFD DO NOT NECESSARILY REPRESENT OFFICIAL OFFICE OF EDU CATION POSITION OR POLICY Perspectives in Reading No. 15 FOLKLORE AND FOLKTALES AROUND THE WORLD Compiled and Edited by Ruth Kearney Carlson California State College at Hayward Prepared by theIRALibrary and Literature Committee Ira INTERNATIONAL READING ASSOCIATION Newark, Delaware 19711 9 b INTERNATIONAL READING ASSOCIATION OFFICERS 1971-1972 President THEODORE L. -

American Studies Through Folktales. PUB DATE 92 NOTE 24P.; Journal Article Offprint

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 393 765 SO 026 134 AUTHOR Pedersen, E. Martin TITLE American Studies through Folktales. PUB DATE 92 NOTE 24p.; Journal article offprint. PUB TYPE Journal Articles (080) JOURNAL CIT Messana: Rassegna Di Studi Filologici Linguistici E Storici; nll p165-185 1992 EDRS PRICE MF01/PC01 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS *American Studies; *Folk Culture; Higher Education; United States History IDENTIFIERS *Folktales; Steinbeck (John); Twain (Mark) ABSTRACT American studies is a combination of fields such as literature, history, phinsophy, politics, and economics. This publication examines how tie different fields of study relate to American studies through folklore or folktales. The use of folktales can provide better illust-ations and understandings of U.S. individuals' heritage and evolution. Famous artists noted for using folktales to describe U.S. culture are Mark Twain and John Steinbeck. (JAG) *********************************************************************** Reproductions supplied by EDRS are the best that can be made from the original document. *********************************************************************** "PERMISSION TO REPRODUCE THIS MATERIAL HAS BEEN GRANTED BY U.S. DEPARTMENT OF EDUCATION Office ol Educational Research and improvement EDUCATIONAL RESOURCES INFORMATION CENTER (ERIC) This document has been reproduced as received from the person or organization TO THE EDUCATIONAL RESOURCES originating it. INFORMATION CENTER (ERIC)." Qs Minor changes have been made to -----------improve reproduction quality. 0 Points of view or opinions staled in this document do not necessarily represent official OERI position or policy. VJ BEST COPY AVAILABLE % AMERICAN STUDIES THROUGH FOLK TALES' Folklore and American studies The basic social sciences, the language arts, and the fine and prac- tical arts all have aspects of similarity, and there is some overlapping among them. -

Cartographers As Critics: Staking Claims in the Mapping of American Literature

Cartographers as Critics: Staking Claims in the Mapping of American Literature by Kyle Carsten Wyatt A thesis submitted in conformity with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of English Collaborative Program in Book History & Print Culture University of Toronto © Copyright by Kyle Carsten Wyatt 2011 Cartographers as Critics: Staking Claims in the Mapping of American Literature Kyle Carsten Wyatt Doctor of Philosophy Department of English Collaborative Program in Book History & Print Culture University of Toronto 2011 Abstract “Cartographers as Critics: Staking Claims in the Mapping of American Literature” recuperates the print culture phenomenon of literary map production, which became popular in North America around 1898. A literary map can be defined as any pictorial map that depicts imaginative worlds or authorial associations across geopolitical space. While notable examples have circulated for centuries in bound books, such as Thomas More’s Utopia and William Faulkner’s Absalom, Absalom!, the majority of twentieth- century literary maps were ephemeral productions that have not survived in great numbers. These discursive documents functioned as compelling expressions of literary taste and cultural values; they circulated in magazines and newspapers, as gas station promotional giveaways and diner placemats, and as classroom “equipment.” Extant literary maps offer new perspectives on turn-of-the-twentieth century U.S. literary nationalism and the Public Library Movement, “fiction debates” and “Great Books” -

DAMMIT, TOTO, WE're STILL in KANSAS: the FALLACY of FEMINIST EVOLUTION in a MODERN AMERICAN FAIRY TALE by Beth Boswell a Diss

DAMMIT, TOTO, WE’RE STILL IN KANSAS: THE FALLACY OF FEMINIST EVOLUTION IN A MODERN AMERICAN FAIRY TALE by Beth Boswell A Dissertation Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in English Middle Tennessee State University May 2018 Dissertation Committee: Dr. Martha Hixon, Director Dr. Will Brantley Dr. Jane Marcellus This dissertation is dedicated, in loving memory, to two dearly departed souls: to Dr. David L. Lavery, the first director of this project and a constant voice of encouragement in my studies, whose absence will never be wholly realized because of the thousands of lives he touched with his spirit, enthusiasm, and scholarship. I am eternally grateful for our time together. And to my beautiful grandmother, Fay M. Rhodes, who first introduced me to the yellow brick road and took me on her back to a pear-tree Emerald City one hundred times or more. I miss you more than Dorothy missed Kansas. ii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This dissertation would not have been possible without the educators who have pushed me to challenge myself, to question everything in the world around me, and to be unashamed to explore what I “thought” I already knew, over and over again. Though there are too many to list by name, know that I am forever grateful for your encouragement and dedication to learning, whether in the classroom or the world. I would like to thank my phenomenal committee for their tireless support and assistance in this project. I am especially grateful for Dr. Martha Hixon, who stepped in as my director after the passing of Dr. -

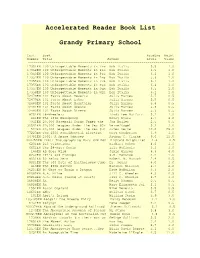

Accelerated Reader Book List Grandy Primary School

Accelerated Reader Book List Grandy Primary School Test Book Reading Point Number Title Author Level Value -------------------------------------------------------------------------- 17351EN 100 Unforgettable Moments in Pro Bob Italia 5.5 1.0 17352EN 100 Unforgettable Moments in Pro Bob Italia 6.5 1.0 17353EN 100 Unforgettable Moments in Pro Bob Italia 6.2 1.0 17354EN 100 Unforgettable Moments in Pro Bob Italia 5.6 1.0 17355EN 100 Unforgettable Moments in Pro Bob Italia 6.1 1.0 17356EN 100 Unforgettable Moments in Pro Bob Italia 6.4 1.0 17357EN 100 Unforgettable Moments in Sum Bob Italia 6.5 1.0 17358EN 100 Unforgettable Moments in Win Bob Italia 6.1 1.0 72478EN 101 Facts About Deserts Julia Barnes 5.7 0.5 72479EN 101 Facts About Lakes Julia Barnes 5.5 0.5 72480EN 101 Facts About Mountains Julia Barnes 5.4 0.5 72481EN 101 Facts About Oceans Julia Barnes 5.8 0.5 72482EN 101 Facts About Rivers Julia Barnes 5.3 0.5 8251EN 18-Wheelers Linda Lee Maifair 5.2 1.0 661EN The 18th Emergency Betsy Byars 4.7 4.0 7351EN 20,000 Baseball Cards Under the Jon Buller 2.5 0.5 30561EN 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea (Gr Verne/Vogel 5.2 3.0 523EN 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea (Un Jules Verne 10.0 28.0 77223EN The 2000 Presidential Election Cory Gunderson 6.9 1.0 34791EN 2001: A Space Odyssey Arthur C. Clarke 9.0 12.0 900355EN 2061: Photographing Mars (MH Edi Richard Brightfiel 4.6 0.5 6201EN 213 Valentines Barbara Cohen 4.0 1.0 6651EN The 24-Hour Genie Lila McGinnis 3.3 1.0 166EN 4B Goes Wild Jamie Gilson 4.6 4.0 8252EN 4X4's and Pickups A.K. -

PRENSES İLE TİLKİ N. Gamze ILICAK Kemal ÇİNKO

Ilıcak, N. G. ve Çinko, K. (2021). Yapay zekânın yarattığı masal: Prenses ile Tilki. Uluslararası Türkçe Edebiyat Kültür Eğitim Dergisi, 10(2), 703-719. Uluslararası Türkçe Edebiyat Kültür Eğitim Dergisi Sayı: 10/2 2021 s. 703-719, TÜRKİYE Araştırma Makalesi YAPAY ZEKÂNIN YARATTIĞI MASAL: PRENSES İLE TİLKİ N. Gamze ILICAK Kemal ÇİNKO Geliş Tarihi: Aralık, 2020 Kabul Tarihi: Nisan, 2021 Öz Günümüz dünyasında yapay zekâ yazılımlarındaki gelişmeler ve bu gelişmelerin yansımaları hayatımızın birçok alanında kendini göstermektedir. Sanal asistanlar, sohbet ve destek botları, oyunlar, akıllı arabalar, akıllı ev sistemleri, güvenlik sistemleri ve daha birçok alanda kullanılan yapay zekâ yazılımları gün geçtikte kullanım sahalarını genişletmektedir. Bu genişleme neticesinde edebiyat alanında da yapay zekâ yaratımı ürünler ortaya çıkarılmaya başlanmıştır. 2018 yılında “Calm” adlı mobil uygulamanın yetkilileri, kullanıcılarına yeni bir masal sunmak istemişler ve bu masalı bir yapay zekâya yazdırmayı amaçlamışlardır. Bu amaç doğrultusunda, Grimm Kardeşler’in masal külliyatıyla eğitilen bir yapay zekâya, yeni bir masal yazdırmayı başarmışlardır. “Kayıp Grimm Masalı” olarak tanıtılan masalın ismi “Prenses ile Tilki”dir. Bu çalışmada öncelikle amaçlanan bu masalın yaratım öyküsünü ve masal metnini sunmak, ayrıca bu masalı halkbilimi araştırmalarına konumlandırabilmek adına fakelore bağlamında incelemektir. Bu amaç doğrultusunda öncelikle Grimm Kardeşler’in masal derleme/yeniden yazma faaliyetleri değerlendirilmiş ve onların bu çalışmaları fakelore bağlamında incelenmiştir. Daha sonra “Prenses ile Tilki” adlı masal fakelore bağlamında ele alınıp bu masalın fakelore ürünü olmaktan ziyade teknolojik yaratımlı yeni nesil bir masal olduğu sonucuna varılmıştır. Türünün tek örneği olan bu masal metni şu an bir meta hükmünde olsa da masalın sözlü geleneğe mal olabileceği gerçeğiyle bu masala yaklaşmak 21. yüzyıl halkbilimi araştırmalarının geleceği için daha doğru olacaktır. -

Surplus Sale Clarkston School District Summer 2016

Surplus Sale Clarkston School District Summer 2016 Books from Parkway Elem: Title / Quantity Publisher Subject Grade Level Copyright Condition Dinosaurs 24 Houghton Mifflin Reading 4 1991 Obsolete Teacher's Manuals 2 Houghton Mifflin Reading 4 1991 Obsolete Mathematics 38 Silver Burdett Math 5 1988 Obsolete Holt Science 18 Holt Renehart Wilslow Science 4 1986 Obsolete Fast as the Wind 30 Houghton Mifflin Reading 5 1991 Obsolete *Also, teacher material for items above* tds 6/21/2016 APPROVED BY THE BOARD OF DIRECTORS ON 6/28/2016 Parkway Elementary May 16, 2016 at 9:29 am Page 1 Discarded Copies (231) by Copy Call Number Alexandria 6.22.7 Selected: Discarded on Date 04/16/2016 - 05/16/2016 - Discarded by Patrons and from Inventory Barcode/ Title/ ISBN/ Site Call #/ Reason Discarded Cost Payment DISCARDED May 12, 2016 14.00 0.00 23744 - Tales from a not-so-dorky drama queen 9781442487697 PARK DISCARDED May 6, 2016 1.00 0.00 21407 - How do baby animals grow? 9781607190349 Weeded PARK DISCARDED 001.9 Taylor, D. Apr 27, 2016 12.95 0.00 4427 - Animal monsters : fantasies and facts of the animal world 0822521768 Weeded PARK DISCARDED 004 McA May 4, 2016 8.00 0.00 18719 - Working with computers 0836842421 Weeded PARK DISCARDED 004 RAU May 4, 2016 17.75 0.00 50745 - The history of the computer 1403496498 Weeded PARK DISCARDED 004.16 Kalbag, Asha May 5, 2016 22.96 0.00 14302 - Homework on your computer 074603346X Weeded PARK DISCARDED 004.16 Meredith, Susan May 5, 2016 22.96 0.00 14303 - Computers 0746034644 Weeded PARK DISCARDED 027 Gibbons, Gail May 5, 2016 89.15 0.00 12667 - Check it out : the book about libraries 0152164006 Weeded PARK DISCARDED 031 Clark, Rob Apr 27, 2016 7.95 0.00 8474 - Why 0516065947 Weeded PARK DISCARDED 031 Reece, C. -

Bibliographies; *Bibliographies; *Childrens Literature; *Instructional Media; *Library Materials; *School Libraries IDENTIFIERS *Appalachia

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 092 127 IR 000 686 AUTHOR Bennett, George B., Ed. TITLE Library Materials for Schools in Appalachia. INSTITUTION West Virginia Univ., Morgantown. Univ. Library. PUB DATE 74 NOTE 73p. 1 AVAILABLE FROM West Virginia University Library, Main Campus, West Virginia University, Morgantown, West Virginia 26505 EDRS PRICE MF-$0.75 HC-$3.15 PLUS POSTAGE DESCRIPTORS Annotated Bibliographies; *Bibliographies; *Childrens Literature; *Instructional Media; *Library Materials; *School Libraries IDENTIFIERS *Appalachia ABSTRACT A product of a library science seminar on Appalachian library materials at West Virginia University, this selective bibliography includes school library materials in print about, relating to, or rooted in Appalachia. There are lists of fiction; poetry; drama; folklore and folk music; biography; history, geography and travel; social and environmental awareness; films; filmstrips; recordings; arts and crafts; natural history and resources; periodicals; and teachers resources. Grade levels are listed separately for fiction; history, geography, and travel; and natural history and resources. Most bibliographic items are annotated. There are lists of film distributors, filmstrip distributors, and record companies. (LS) (.1 LIBRARY MATERIALS cz) FOR SCHOOLS IN APPALACHIA 9 0 0 WEST VIRGINIA UNIVERSITY (x. -1 LIBRARY MATERIALS FOR SCHOOLS IN APPALACHIA Edited by George E. Bennett US DEPARTMENT OF HEALTH. FOUCATICIN & WELFARE NATIONAL INSTITUTE OF EDUCA TION tr.1.1D'7,JVIENT HAS BEEN REP,,0 (,,;(FD ""NCTLY AS RECEIVZ-0 ritCA0 Tr'E PV?S',..4 OR ORGANIZATION ORIGIN A-IVS IT ROiNTS Cr VIEW OR OPINION; ATED DO NOT NECESSARILY RE PRE SCNT OTriCo At Ne, tiONAL INSTITUTE OF CT....CA TIDY PDS' POLICY West Virginia University Library Morgantown 1974 TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction 1.1I atcraliiri.: l'ocir and Malmo', 2 1,1 lientilihir, 1.11 irti+n :3 1.2 Junior 1.,0.1 Fiction 1,:3 High1 a.% el Pillion 1'1 . -

Fall 2005 Kerlan Collection Newsletter

Paul Bunyan Collection http://special.lib.umn.edu/findaid/xml/CLRC-1946.xml 113 Elmer L. Andersen Library, University of Minnesota, 222 21st Avenue South, Minneapolis, MN 55455 CLRC Home Page | Return to CLRC Finding Aid Index| Contact the Kerlan Collection Paul Bunyan Collection Finding Aid Written By: John Barneson, Jim Eyer, and E.B. Stanford Summary Collection Summary Information Creator: Charters, W.W., Stanford, E.B. Collection Overview Title: Paul Bunyan Collection Collection Scope and Content CLRC-1946 Number: Restrictions Location: See Detailed Descriptions for Each Title Item for Box Locations Indexing Terms Repository: University of Minnesota Libraries Children's Literature Research Collections Administrative Information Collection Collection Overview Contents Series 1a: The Paul Bunyan Collection of the Children's Literature Research Collections, at the University Monographs of Minnesota, was established in 1960 with the gift of an extensive group of books, pamphlets, (Books) - Paul photographs, etc., the result of many years' active collecting by the late Professor W. W. Bunyan Charters of Ohio State University. Since then gifts from a variety of friends and purchases by Collection the library have produced a sizeable assemblage of books, manuscripts, pamphlets, reprints, newspaper clippings, drawings, photographs, phonograph records and other memorabilia. Series 1b: Monographs Among much noteworthy material are the W. B. Laughead papers, secured through the good (Books) offices of Elwood Maunder, Executive Director, Forest History Foundation, and which include Archival inter alia original cartoons, extensive correspondence - mainly with Max Gartenberg, Louis A. Collection Maier, Franklin J. Meine and Archie Walker, sketches and finished drawings, a file of Red Series 2: River Lumber Company ads from the American Lumberman and Mississippi Valley Periodicals Lumberman from 1915 to 1949, and stories both in pamphlet and manuscript form.