Print This Article

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Reading the Miraculous Powers of Japanese Poetry Spells, Truth Acts, and a Medieval Buddhist Poetics of the Supernatural

Japanese Journal of Religious Studies 32/: –33 © 2005 Nanzan Institute for Religion and Culture R. Keller Kimbrough Reading the Miraculous Powers of Japanese Poetry Spells, Truth Acts, and a Medieval Buddhist Poetics of the Supernatural The supernatural powers of Japanese poetry are widely documented in the lit- erature of Heian and medieval Japan. Twentieth-century scholars have tended to follow Orikuchi Shinobu in interpreting and discussing miraculous verses in terms of ancient (arguably pre-Buddhist and pre-historical) beliefs in koto- dama 言霊, “the magic spirit power of special words.” In this paper, I argue for the application of a more contemporaneous hermeneutical approach to the miraculous poem-stories of late-Heian and medieval Japan: thirteenth- century Japanese “dharani theory,” according to which Japanese poetry is capable of supernatural effects because, as the dharani of Japan, it contains “reason” or “truth” (kotowari) in a semantic superabundance. In the first sec- tion of this article I discuss “dharani theory” as it is articulated in a number of Kamakura- and Muromachi-period sources; in the second, I apply that the- ory to several Heian and medieval rainmaking poem-tales; and in the third, I argue for a possible connection between the magico-religious technology of Indian “Truth Acts” (saccakiriyā, satyakriyā), imported to Japan in various sutras and sutra commentaries, and some of the miraculous poems of the late- Heian and medieval periods. keywords: waka – dharani – kotodama – katoku setsuwa – rainmaking – Truth Act – saccakiriyā, satyakriyā R. Keller Kimbrough is an Assistant Professor of Japanese at Colby College. In the 2005– 2006 academic year, he will be a Visiting Research Fellow at the Nanzan Institute for Religion and Culture. -

I TEAM JAPAN: THEMES of 'JAPANESENESS' in MASS MEDIA

i TEAM JAPAN: THEMES OF ‘JAPANESENESS’ IN MASS MEDIA SPORTS NARRATIVES A Dissertation submitted to the Temple University Graduate Board In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy by Michael Plugh July 2015 Examining Committee Members: Fabienne Darling-Wolf, Advisory Chair, Media and Communication Doctoral Program Nancy Morris, Media and Communication Doctoral Program John Campbell, Media and Communication Doctoral Program Lance Strate, External Member, Fordham University ii © Copyright 2015 by MichaelPlugh All Rights Reserved iii Abstract This dissertation concerns the reproduction and negotiation of Japanese national identity at the intersection between sports, media, and globalization. The research includes the analysis of newspaper coverage of the most significant sporting events in recent Japanese history, including the 2014 Koshien National High School Baseball Championships, the awarding of the People’s Honor Award, the 2011 FIFA Women’s World Cup, wrestler Hakuho’s record breaking victories in the sumo ring, and the bidding process for the 2020 Olympic Games. 2054 Japanese language articles were examined by thematic analysis in order to identify the extent to which established themes of “Japaneseness” were reproduced or renegotiated in the coverage. The research contributes to a broader understanding of national identity negotiation by illustrating the manner in which established symbolic boundaries are reproduced in service of the nation, particularly via mass media. Furthermore, the manner in which change is negotiated through processes of assimilation and rejection was considered through the lens of hybridity theory. iv To my wife, Ari, and my children, Hiroto and Mia. Your love sustained me throughout this process. -

UC Irvine UC Irvine Electronic Theses and Dissertations

UC Irvine UC Irvine Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title Soteriology in the Female-Spirit Noh Plays of Konparu Zenchiku Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/7bk827db Author Chudnow, Matthew Thomas Publication Date 2017 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA, IRVINE Soteriology in the Female-Spirit Noh Plays of Konparu Zenchiku DISSERTATION submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSPHY in East Asian Languages and Literatures by Matthew Chudnow Dissertation Committee: Associate Professor Susan Blakeley Klein, Chair Professor Emerita Anne Walthall Professor Michael Fuller 2017 © 2017 Matthew Chudnow DEDICATION To my Grandmother and my friend Kristen オンバサラダルマキリソワカ Windows rattle with contempt, Peeling back a ring of dead roses. Soon it will rain blue landscapes, Leading us to suffocation. The walls structured high in a circle of oiled brick And legs of tin- Stonehenge tumbles. Rozz Williams Electra Descending ii TABLE OF CONTENTS Page ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS iv CURRICULUM VITAE v ABSTRACT OF DISSERTATION vi INTRODUCTION 1 CHAPTER 1: Soteriological Conflict and 14 Defining Female-Spirit Noh Plays CHAPTER 2: Combinatory Religious Systems and 32 Their Influence on Female-Spirit Noh CHAPTER 3: The Kōfukuji-Kasuga Complex- Institutional 61 History, the Daijōin Political Dispute and Its Impact on Zenchiku’s Patronage and Worldview CHAPTER 4: Stasis, Realization, and Ambiguity: The Dynamics 95 of Nyonin Jōbutsu in Yōkihi, Tamakazura, and Nonomiya CONCLUSION 155 BIBLIOGRAPHY 163 iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This dissertation is the culmination of years of research supported by the department of East Asian Languages & Literatures at the University of California, Irvine. -

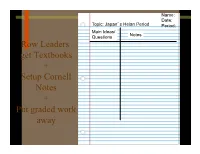

7.5 Heian Notes

Name: Date: Topic: Japan’s Heian Period Period: Main Ideas/ Questions Notes Row Leaders get Textbooks + Setup Cornell Notes + Put graded work away A New Capital • In 794, the Emperor Kammu built a new capital city for Japan, called Heian-Kyo. • Today, it is called Kyoto. • The Heian Period is called Japan’s “Golden Age” Essential Question: What does “Golden Age” mean? Inside the city • Wealthy families lived in mansions surrounded by gardens. A Powerful Family • The Fujiwara family controlled Japan for over 300 years. • They had more power than the emperor and made important decisions for Japan. Beauty and Fashion • Beauty was important in Heian society. • Men and women blackened their teeth. • Women plucked their eyebrows and painted them higher on their foreheads. Beauty and Fashion • Heian women wore as many as 12 silk robes at a time. • Long hair was also considered beautiful. Entertainment • The aristocracy had time for diversions such as go (a board game), kemari (keep the ball in play) and bugaku theater. Art • Yamato-e was a style of Japanese art that reflected nature from the Japanese religion of Shinto. Writing and Literature • The Tale of Genji was written by Murasaki Shikibu, a woman, and is considered the world’s first novel. Japanese Origami Book Blah blah blah blah. Blah blah blah blah. Blah blah blah blah. Blah blah blah blah. Blah blah blah blah. Blah blah blah blah. . -

Bonsai Pdf 5/31/06 11:18 AM Page 1

Bonsai pdf 5/31/06 11:18 AM Page 1 THE BONSAI COLLECTION The Chicago Botanic Garden’s bonsai collection is regarded by bonsai experts as one of the best public collections in the world. It includes 185 bonsai in twenty styles and more than 40 kinds of plants, including evergreen, deciduous, tropical, flowering and fruiting trees. Since the entire collection cannot be displayed at once, select species are rotated through a display area in the Education Center’s East Courtyard from May through October. Each one takes the stage when it is most beautiful. To see photographs of bonsai from the collection, visit www.chicagobotanic.org/bonsai. Assembling the Collection Predominantly composed of donated specimens, the collection includes gifts from BONSAI local enthusiasts and Midwest Bonsai Society members. In 2000, Susumu Nakamura, a COLLECTION Japanese bonsai master and longstanding friend of the Chicago Botanic Garden, donated 19 of his finest bonsai to the collection. This A remarkable collection gift enabled the collection to advance to of majestic trees world-class status. in miniature Caring for the Collection When not on display, the bonsai in the Chicago Botanic Garden’s collection are housed in a secured greenhouse that has both outdoor and indoor facilities. There the bonsai are watered, fertilized, wired, trimmed and repotted by staff and volunteers. Several times a year, bonsai master Susumu Nakamura travels from his home in Japan to provide guidance for the care and training of this important collection. What Is a Bonsai? Japanese and Chinese languages use the same characters to represent bonsai (pronounced “bone-sigh”). -

Advanced Master Gardener Landscape Gardening For

ADVANCED MASTER GARDENER LANDSCAPE GARDENING FOR GARDENERS 2002 The Quest Continues 11 ADVANCED MASTER GARDENER 2002 LARRY A. SAGERS PROFFESOR UTAH STATE UNIVERSITY 21 ADVANCED MASTER GARDENER 2002 GRETCHEN CAMPBELL • MASTER GARDENER COORDINATOR AT THANKSGIVING POINT INSTITUE 31 ADVANCED MASTER GARDENER 2002 41 ADVANCED MASTER GARDENER 2002 HISTORY OF EARLY GARDENING • Life according to the Bible began in a garden. • Wherever that garden was located that was planted eastward in Eden, there were many plants that Adam and Eve were to tend. • The Garden provided”every tree that is pleasant to the sight and good for food” 51 ADVANCED MASTER GARDENER 2002 HISTORY OF EARLY GARDENING • Other cultures have similar stories. • Stories come from Native Americans African tribes, Polynesians and Aborigines and many other groups of gardens as a place of life 61 ADVANCED MASTER GARDENER 2002 HISTORY OF EARLY GARDENING • Teachings and legends influence art, religion, education and gardens. • The how and why of the different geographical and cultural influences on Landscape Gardening is the theme of the 2002 Advanced Master Gardening course at Thanksgiving Point Institute. 71 ADVANCED MASTER GARDENER 2002 HISTORY OF EARLY GARDENING • Earliest known indications of Agriculture only go back about 10,000 years • Bouquets of flowers have been found in tombs some 60,000 years old • These may have had aesthetic or ritual roles 81 ADVANCED MASTER GARDENER 2002 HISTORY OF EARLY GARDENING • Evidence of gardens in the fertile crescent between the Tigris and Euphrates -

Samurai Life in Medieval Japan

http://www.colorado.edu/ptea-curriculum/imaging-japanese-history Handout M2 (Print Version) Page 1 of 8 Samurai Life in Medieval Japan The Heian period (794-1185) was followed by 700 years of warrior governments—the Kamakura, Muromachi, and Tokugawa. The civil government at the imperial court continued, but the real rulers of the country were the military daimy class. You will be using art as a primary source to learn about samurai and daimy life in medieval Japan (1185-1603). Kamakura Period (1185-1333) The Kamakura period was the beginning of warrior class rule. The imperial court still handled civil affairs, but with the defeat of the Taira family, the Minamoto under Yoritomo established its capital in the small eastern city of Kamakura. Yoritomo received the title shogun or “barbarian-quelling generalissimo.” Different clans competed with one another as in the Hgen Disturbance of 1156 and the Heiji Disturbance of 1159. The Heiji Monogatari Emaki is a hand scroll showing the armor and battle strategies of the early medieval period. The conflict at the Sanj Palace was between Fujiwara Nobuyori and Minamoto Yoshitomo. As you look at the scroll, notice what people are wearing, the different roles of samurai and foot soldiers, and the different weapons. What can you learn about what is involved in this disturbance? What can you learn about the samurai and the early medieval period from viewing this scroll? What information is helpful in developing an accurate view of samurai? What preparations would be necessary to fight these kinds of battles? (Think about the organization of people, equipment, and weapons; the use of bows, arrows, and horses; use of protective armor for some but not all; and the different ways of fighting.) During the Genpei Civil War of 1180-1185, Yoritomo fought against and defeated the Taira, beginning the Kamakura Period. -

A COMPARISON of the MURASAKI SHIKIBU DIARY and the LETTER of ABUTSU Carolina Negri

Rivista degli Studi Orientali 2017.qxp_Impaginato 26/02/18 08:37 Pagina 281 REFERENCE MANUALS FOR YOUNG LADIES-IN-WAITING: A COMPARISON OF THE MURASAKI SHIKIBU DIARY AND THE LETTER OF ABUTSU Carolina Negri The nature of the epistolary genre was revealed to me: a form of writing devoted to another person. Novels, poems, and so on, were texts into which others were free to enter, or not. Letters, on the other hand, did not exist without the other person, and their very mission, their signifcance, was the epiphany of the recipient. Amélie Nothomb, Une forme de vie The paper focuses on the comparison between two works written for women’s educa- tion in ancient Japan: The Murasaki Shikibu nikki (the Murasaki Shikibu Diary, early 11th century) and the Abutsu no fumi (the Letter of Abutsu, 1263). Like many literary docu- ments produced in the Heian (794-1185) and in the Kamakura (1185-1333) periods they describe the hard life in the service of aristocratic fgures and the difculty of managing relationships with other people. Both are intended to show women what positive ef- fects might arise from sharing certain examples of good conduct and at the same time, the inevitable negative consequences on those who rejected them. Keywords: Murasaki Shikibu nikki; Abutsu no fumi; ladies-in.waiting; letters; women’s education 1. “The epistolary part” of the Murasaki Shikibu Diary cholars are in agreement on the division of the contents of Murasaki Shikibu nikki (the Murasaki Shikibu Diary, early 11th century) into four dis- Stinct parts. The frst, in the style of a diary (or an ofcial record), presents events from autumn 1008 to the following New Year, focusing on the birth of the future heir to the throne, Prince Atsuhira (1008-1036). -

Japanese Studies Review, Vol. XX (2016), Pp

ISSN: 1500-0713 ______________________________________________________________ Article Title: Performing Prayer, Saving Genji, and Idolizing Murasaki Shikibu: Genji Kuyō in Nō and Jōruri Author(s): Satoko Naito Source: Japanese Studies Review, Vol. XX (2016), pp. 3-28 Stable URL: https://asian.fiu.edu/projects-and-grants/japan-studies- review/journal-archive/volume-xx-2016/naito-satoko- gkuyojoruri_jsr.pdf ______________________________________________________________ PERFORMING PRAYER, SAVING GENJI, AND IDOLIZING MURASAKI SHIKIBU: GENJI KUYŌ IN NŌ AND JŌRURI1 Satoko Naito University of Maryland, College Park Introduction The Murasaki Shikibu daraku ron [lit. “Story of Murasaki Shikibu’s Fall] tells that after her death Murasaki Shikibu (d. ca. 1014) was cast to hell.2 The earliest reference is found in Genji ipponkyō [Sutra for Genji] (ca. 1166), which recounts a Buddhist kuyō (dedicatory rite) performed on her behalf, with the reasoning that the Heian author had been condemned to eternal suffering in hell for writing Genji monogatari [The Tale of Genji] (ca. 1008). Though Genji ipponkyō makes no explicit claim to the efficacy of the kuyō, its performance is presumably successful and saves the Genji author. In such a case the earliest extant utterance of the Murasaki-in-hell story is coupled with her subsequent salvation, and the Genji author, though damned, is also to be saved.3 It may be more accurate, then, to say that the Murasaki Shikibu daraku ron is about Murasaki Shikibu’s deliverance, rather than her fall (daraku). Through the medieval period and beyond, various sources recounted the execution of kuyō rites conducted for The Tale of Genji’s author, often initiated and sponsored by women.4 Such stories of Genji kuyō 1 Author’s Note: I thank those who commented on earlier versions of this paper, in particular D. -

Heian Court Poetry-1.Indd

IND TRO UCTION The Francesists know about French matters, the Germanists about German matters, the other specialists know about their own matters; those who know about marginal and minor literary cultures are very few; the Italianists mostly know only about Italian matters, and this is quite a problem. (Remo Ceserani) In recent years the definition of ‘World Literature’ has been object of at- tention for a growing number of scholars. As the globalized and intercon- nected world of the 21st century is facing new challenges concerning politics, economics, the environment, as a result, also the academic world has become increasingly globalized and interconnected, not only in the fields of Natural or Social sciences, but also as regards the Humanities and in particular Lit- erature, traditionally considered the most conservative and ‘classical’ field in academic studies. The problem about the universal definition of ‘Literature’ has always been extremely complex, because as stated by Remo Ceserani «for the common experience, the meanings of the term literature, and the various concepts conceived in the course of time, seem to be numerous, diversified, and incompatible with each other» (Ceserani 1999, p. 3). Nevertheless, with the relatively new definition of World Literature, many scholars (Damrosh, Moretti, Pizer etc.) expressed the need to face the problem of re-defining the very concept of Literature, starting from the correction of its Eurocentric tendencies and its distinction between ‘main’ literatures and ‘peripheral’ or ‘minor’ literatures, -

Discourses of the Heian Era and National Identity Formation in Contemporary Japan Hennessey, John L

Discourses of the Heian Era and National Identity Formation in Contemporary Japan Hennessey, John L. 2015 Document Version: Publisher's PDF, also known as Version of record Link to publication Citation for published version (APA): Hennessey, J. L. (2015). Discourses of the Heian Era and National Identity Formation in Contemporary Japan. (Working papers in contemporary Asian studies; No. 43). Centre for East and South-East Asian Studies, Lund University. Total number of authors: 1 General rights Unless other specific re-use rights are stated the following general rights apply: Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the public portal are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. • Users may download and print one copy of any publication from the public portal for the purpose of private study or research. • You may not further distribute the material or use it for any profit-making activity or commercial gain • You may freely distribute the URL identifying the publication in the public portal Read more about Creative commons licenses: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/ Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact us providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. LUND UNIVERSITY PO Box 117 221 00 Lund +46 46-222 00 00 Download date: 25. Sep. 2021 Discourses of the Heian Era and National Identity Formation in Contemporary Japan John L. Hennessey Working Paper No 43 2015 Centre for East and South-East Asian Studies Lund University, Sweden www.ace.lu.se * John L. -

Trans-Gender Themes in Japanese Literature from the Medieval to Meiji Eras

University of Massachusetts Amherst ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst Masters Theses Dissertations and Theses July 2017 Trans-gender Themes in Japanese Literature From the Medieval to Meiji Eras Jessica Riggan University of Massachusetts Amherst Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umass.edu/masters_theses_2 Part of the Japanese Studies Commons Recommended Citation Riggan, Jessica, "Trans-gender Themes in Japanese Literature From the Medieval to Meiji Eras" (2017). Masters Theses. 532. https://doi.org/10.7275/10139588 https://scholarworks.umass.edu/masters_theses_2/532 This Open Access Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Dissertations and Theses at ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. It has been accepted for inclusion in Masters Theses by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Trans-Gender Themes in Japanese Literature from the Medieval to Meiji Eras A Thesis Presented by Jessica Riggan Submitted to the Graduate School of the University of Massachusetts Amherst in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS May 2017 Japanese Asian Languages and Cultures Trans-Gender Themes in Japanese Literature from the Medieval to Meiji Eras A Thesis Presented By JESSICA RIGGAN Approved as to style and content by: Stephen Miller, Chair Amanda Seaman, Member Bruce Baird, Member Bruce Baird, Unit Director Japanese Languages and Cultures Part of the Department of Languages, Literatures, and Cultures William Moebius, Department Head Department of Languages, Literatures, and Cultures ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to thank my thesis advisor, Professor Stephen Miller, for his continued guidance and patience during my thesis-writing process.