Vii . the Second “Going It Alone” in Times of Ending the Cold War: Negotiations with Brussels and Eu Entry 1987–95

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

From the History of Polish-Austrian Diplomacy in the 1970S

PRZEGLĄD ZACHODNI I, 2017 AGNIESZKA KISZTELIŃSKA-WĘGRZYŃSKA Łódź FROM THE HISTORY OF POLISH-AUSTRIAN DIPLOMACY IN THE 1970S. AUSTRIAN CHANCELLOR BRUNO KREISKY’S VISITS TO POLAND Polish-Austrian relations after World War II developed in an atmosphere of mutu- al interest and restrained political support. During the Cold War, the Polish People’s Republic and the Republic of Austria were on the opposite sides of the Iron Curtain; however, after 1945 both countries sought mutual recognition and trade cooperation. For more than 10 years following the establishment of diplomatic relations between Austria and Poland, there had been no meetings at the highest level.1 The first con- tact took place when the then Minister of Foreign Affairs, Bruno Kreisky, came on a visit to Warsaw on 1-3 March 1960.2 Later on, Kreisky visited Poland four times as Chancellor of Austria: in June 1973, in late January/early February 1975, in Sep- tember 1976, and in November 1979. While discussing the significance of those five visits, it is worth reflecting on the role of Austria in the diplomatic activity of the Polish Ministry of Foreign Affairs (MFA). The views on the motives of the Austrian politician’s actions and on Austria’s foreign policy towards Poland come from the MFA archives from 1972-1980. The time period covered in this study matches the schedule of the Chancellor’s visits. The activity of the Polish diplomacy in the Communist period (1945-1989) has been addressed as a research topic in several publications on Polish history. How- ever, as Andrzej Paczkowski says in the sixth volume of Historia dyplomacji polskiej (A history of Polish diplomacy), research on this topic is still in its infancy.3 A wide range of source materials that need to be thoroughly reviewed offer a number of 1 Stosunki dyplomatyczne Polski, Informator, vol. -

The Economics of Neutrality: Spain, Sweden and Switzerland in the Second World War

The Economics of Neutrality: Spain, Sweden and Switzerland in the Second World War Eric Bernard Golson The London School of Economics and Political Science A thesis submitted to the Department of Economic History of the London School of Economics for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, London, 15 June 2011. Declaration I certify that the thesis I have presented for examination for the MPhil/PhD degree of the London School of Economics and Political Science is solely my own work other than where I have clearly indicated that it is the work of others. The copyright of this thesis rests with the author. Quotation from it is permitted, provided that full acknowledgement is made. This thesis may not be reproduced without the prior written consent of the author. I warrant that this authorization does not, to the best of my belief, infringe the rights of any third party. ‐ 2 ‐ Abstract Neutrality has long been seen as impartiality in war (Grotius, 1925), and is codified as such in The Hague and Geneva Conventions. This dissertation empirically investigates the activities of three neutral states in the Second World War and determines, on a purely economic basis, these countries actually employed realist principles to ensure their survival. Neutrals maintain their independence by offering economic concessions to the belligerents to make up for their relative military weakness. Depending on their position, neutral countries can also extract concessions from the belligerents if their situation permits it. Despite their different starting places, governments and threats against them, Spain, Sweden and Switzerland provided similar types of political and economic concessions to the belligerents. -

Second Uncorrected Proof ~~~~ Copyright

Into the Groove ~~~~ SECOND UNCORRECTED PROOF ~~~~ COPYRIGHT-PROTECTED MATERIAL Do Not Duplicate, Distribute, or Post Online Hurley.indd i ~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~11/17/2014 5:57:47 PM Studies in German Literature, Linguistics, and Culture ~~~~ SECOND UNCORRECTED PROOF ~~~~ COPYRIGHT-PROTECTED MATERIAL Do Not Duplicate, Distribute, or Post Online Hurley.indd ii ~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~11/17/2014 5:58:39 PM Into the Groove Popular Music and Contemporary German Fiction Andrew Wright Hurley Rochester, New York ~~~~ SECOND UNCORRECTED PROOF ~~~~ COPYRIGHT-PROTECTED MATERIAL Do Not Duplicate, Distribute, or Post Online Hurley.indd iii ~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~11/17/2014 5:58:39 PM This project has been assisted by the Australian Government through the Australian Research Council. The views expressed herein are those of the author and are not necessarily those of the Australian Research Council. Copyright © 2015 Andrew Wright Hurley All Rights Reserved. Except as permitted under current legislation, no part of this work may be photocopied, stored in a retrieval system, published, performed in public, adapted, broadcast, transmitted, recorded, or reproduced in any form or by any means, without the prior permission of the copyright owner. First published 2015 by Camden House Camden House is an imprint of Boydell & Brewer Inc. 668 Mt. Hope Avenue, Rochester, NY 14620, USA www.camden-house.com and of Boydell & Brewer Limited PO Box 9, Woodbridge, Suffolk IP12 3DF, UK www.boydellandbrewer.com ISBN-13: 978-1-57113-918-4 ISBN-10: 1-57113-918-4 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data CIP data applied for. This publication is printed on acid-free paper. Printed in the United States of America. -

Conservative Central Office 32 Smith Square Westminster SWIP 3HH Tel

t. r Conservative Central Office 32 Smith Square Westminster SWIP 3HH Tel. 01-222 9000 Telex 8814563 From THE CHAIRMAN OF THE PARTY John Selwyn Gummer MP November 1984 As you will recall, I led a group of twelve parliamentary colleagues to Bonn earlier this month to meet with members of the CDU/CSU parliamentary group. increasing number of daTacts be'tween all levels of our parties over the last four years, greatly assisted by the London office of the Konrad Adenauer Foundation, this was the first such meeting of its kind. The main objective on this occasion was to begin the process of establishing close friendly relationships between individual members, and good progress was made towards this. Some thirty CDU/CSU members participated in our discussions, which broadly covered three areas: the European contribution to strengthening the Atlantic Alliance; the European role in East/West policy; and European economic integration as a force for international competitiveness. The contributions were even more free- ranging than these headings suggest, and their value lay rather more in the informative nature of the exchange of views for individual members than in breaking any new ground. Nevertheless, it is worth underlining the emphasis generally placed by German members on the development of European defence policy, in harmony with overall NATO strategy; and, in particular, their view that the Western European Union should be given a more dynamic role. It was also noteworthy that some Germans expressed the hope that their government would take a more liberal attitude towards internal Community competition (even in the field of insurance and lorry permits!). -

Encounters with Wolves

Marlis Heyer Susanne Hose Hrsg. Mały rjad Serbskeho instituta Budyšin Kleine Reihe des Sorbischen Instituts Bautzen 32 Encounters with Wolves: Dynamics and Futures Begegnungen mit Wölfen Zetkanja z wjelkami 32 · 2020 Mały rjad Serbskeho instituta Budyšin Kleine Reihe des Sorbischen Instituts Bautzen Marlis Heyer Susanne Hose Hrsg. Encounters with Wolves: Dynamics and Futures Begegnungen mit Wölfen Zetkanja z wjelkami © 2020 Serbski institut Budyšin Sorbisches Institut Bautzen Dwórnišćowa 6 · Bahnhofstraße 6 D-02625 Budyšin · Bautzen Spěchowane wot Załožby za serbski lud, kotraž T +49 3591 4972-0 dóstawa lětnje přiražki z dawkowych srědkow na F +49 3591 4972-14 zakładźe hospodarskich planow, wobzamknjenych www.serbski-institut.de wot zapósłancow Zwjazkoweho sejma, Krajneho sejma Braniborska a Sakskeho krajneho sejma. [email protected] Gefördert durch die Stiftung für das sorbische Redakcija Redaktion Volk, die jährlich auf der Grundlage der von den Marlis Heyer, Susanne Hose Abgeordneten des Deutschen Bundestages, des Landtages Brandenburg und des Sächsischen Wuhotowanje Gestaltung Landtages beschlossenen Haushalte Zuwen- Ralf Reimann, Büro für Gestaltung, dungen aus Steuermitteln erhält. Bautzen Ćišć Druck Grafik S. 33 unter Verwendung eines 32 Union Druckerei Dresden GmbH Scherenschnitts von Elisabeth Müller, Collmen Mały rjad Serbskeho instituta Budyšin ISBN 978-3-9816961-7-2 Grafik S. 87 nach GEO-Karte 5/2018 Kleine Reihe des Sorbischen Instituts Bautzen Page Content 5 Marlis Heyer and Susanne Hose Vorwort · Preface 23 Emilia -

Introduction: Our Athens Spring

Introduction: Our Athens Spring Let me tell you why I am here with words I have borrowed from a famous old manifesto. I am here because: A spectre is haunting Europe — the spectre of democracy. All the powers of old Europe have entered into a holy alliance to exorcise this spectre: The state- sponsored bankers and the Eurogroup, the Troika and Dr Schäuble, Spain’s heirs of Franco’s political legacy and the SPD’s Berlin leadership, Baltic governments that subJected their populations to terrible, unnecessary recession and Greece’s resurgent oligarchy. I am here in front of you because a small nation chose to oppose this holy alliance. To look at them in the eye and say: Our liberty is not for sale. Our dignity is not for auction. If we give up liberty and dignity, as you demand that we do, Europe will lose its integrity and forfeit its soul. I am here in front of you because nothing good happens in Europe if it does not start from France. I am here in front of you because the Athens Spring that united Greeks and gave them back • their smile • their courage • their freedom from fear • the strength to say NO to irrationality • NO to un-freedom • NO to a subJugation that in the end does not benefit even Europe’s strong and mighty, …that magnificent Athens Spring, which culminated in a 62% saying a majestic NO to Un-Reason and to Misanthropy,… …our Athens Spring, was also a chance for a Paris Spring, a Frangy Spring, a Berlin, a Madrid, a Dublin, a Helsinki, a Bratislava, a Vienna Spring. -

Statement of the Director General to the 21St Session of the General Conference of the IAEA

Statement of the Director General to the 21st Session of the General Conference of the IAEA INTRODUCTORY REMARKS May I first express our warmest thanks to President Kirchschlager for his kindness in joining us today to celebrate the twentieth anniversary of the International Atomic Energy Agency and for his thoughtful statement. His interest in and support for the Agency is evidenced by the fact that this is the second time this year that he has assisted in opening one of our meetings, the previous occasion being the Salzburg Conference in May. I would also like to convey through him to the Government and people of Austria and to the City of Vienna our sincere appreciation for the twenty years of generous and unfailing hospitality and understanding that the Agency has enjoyed in the city and in this country. I would like to thank the President of the National Council, Mr. Anton Benya, and the Minister for Foreign Affairs, Dr. Willibald Pahr, for honouring this conference with their presence. The founders of the Agency showed wisdom not only in the far-sighted provisions of the Agency's Statute but also in the selection of Vienna as the permanent headquarters of the Agency, a choice which has encouraged other United Nations organizations to come here, such as our sister organization UN I DO, and which I hope will be followed by many more. I should like to extend a special welcome to our guests of honour, each of whom has played a significant role in the history of the Agency. These include: Ambassador G.P. -

The Legacy of Neutrality in Finnish and Swedish Security Policies in Light of European Integration

Traditions, Identity and Security: the Legacy of Neutrality in Finnish and Swedish Security Policies in Light of European Integration. Johan Eliasson PhD Candidate/Instructor Dep. Political Science 100 Eggers Hall Maxwell school of Citizenship and Public Affairs Syracuse University Syracuse, NY 13244-1090 Traditions, Identity and Security 2 . Abstract The militarily non-allied members of the European Union, Austria, Finland, Ireland and Sweden, have undergone rapid changes in security policies since 1999. Looking at two states, Finland and Sweden, this paper traces states’ contemporary responses to the rapid development of the European Security and Defense Policy (ESDP) to their historical experiences with different types of neutrality. It is argued that by looking at the legacies of different types of neutrality on identity and domestic rules, traditions, norms, and values, we can better explain how change occurred, and why states have pursued slightly different paths. This enhances our understanding broadly of the role of domestic institutions in accounting for policy variation in multilateral regional integration, and particularly in the EU. In the process, this study also addresses a question recently raised by other scholars: the role of neutrality in Europe. Traditions, Identity and Security 3 . 1. Introduction The core difference between members and non-members of a defense alliance lie in obligations to militarily aid a fellow member if attacked, and, to this end, share military strategy and related information. The recent and rapid institutionalization of EU security and defense policy is blurring this distinction beyond the increased cooperation and solidarity emanating from geopolitical changes, NATO’s expansion and new-found role in crisis management, or, later, the 9/11 attacks. -

Die KPÖ in Der Konzentrationsregierung 1945–1947: Energieminister Karl Altmann WINFRIED R

12. Jg. / Nr. 3 ALFRED KLAHR GESELLSCHAFT September 2005 MITTEILUNGEN Preis: 1,1– Euro Die KPÖ in der Konzentrationsregierung 1945–1947: Energieminister Karl Altmann WINFRIED R. GARSCHA er im „Österreich-Lexikon“ war – und hier ist den Autoren der Par- Das, was über die Kenntnis einer bis- nach Karl Altmann sucht, fin- teigeschichte zuzustimmen – der Ab- lang unbekannten Facette der öster- Wdet einen dreieinhalbzeilige schluss einer Entwicklung, die bereits reichischen Nachkriegsgeschichte hinaus Eintrag mit den Geburts- und Sterbeda- mit der Ersetzung der kommunistischen am Wirken Altmanns als Energiemini- ten, dem Berufstitel (Obersenatsrat der durch ehemalige Nazi-Polizisten ab dem ster von Interesse ist, bezieht sich vor al- Gemeinde Wien) und der Mitteilung, Frühjahr 1947 in größerem Umfang be- lem auf die Bedingungen, unter denen er dass der KPÖ-Politiker 1945–47 Bun- gonnen hatte und ihren Höhepunkt mit kommunistische Politik betrieb: In einer desminister für Elektrifizierung und En- der Abberufung des kommunistischen absoluten Minderheitsposition als einzi- ergiewirtschaft gewesen sei.1 Leiters des staatspolizeilichen Büros der ger Minister seiner Partei in einer Regie- Auf den immerhin fast 600 Seiten der Bundespolizeidirektion Wien, Heinrich rung, deren übrige Mitglieder in ihm eine KPÖ-Geschichte2 wird Karl Altmann Dürmayer, im September 1947 erreicht Art Agenten der sowjetischen Besat- ganze zwei Mal kurz erwähnt. Einmal im hatte. Der internationale Bezug war der zungsmacht erblickten (was mit ihrem Zusammenhang mit seiner Entsendung 1947 voll ausbrechende Kalte Krieg, in eigenen Selbstverständnis als bedin- in die Bundesregierung als KPÖ-Mini- ganz Nord-, West- und Südeuropa wur- gungslose Parteigänger des „Westens“ ster, der der Partei eine „Kontrollmög- den kommunistische Minister aus den korrelierte), mit einem Beamtenapparat, lichkeit über die Regierungspolitik“ si- Regierungen gedrängt (übrigens viele der – von ganz wenigen, durch ihn selbst chern sollte (S. -

Freiheits- Und Einheitsdenkmal Gestalten

Deutscher Bundestag Drucksache 16/… 16. Wahlperiode 03.12.2008 Antrag der Abgeordneten Wolfgang Börnsen (Bönstrup), Peter Albach, Dorothee Bär, Renate Blank, Gitta Connemann, Dr. Stephan Eisel, Reinhard Grindel, Monika Grütters, Kristina Köhler (Wiesbaden), Hartmut Koschyk, Dr. Günter Krings, Maria Michalk, Philipp Mißfelder, Rita Pawelski, Beatrix Philipp, Dr. Norbert Röttgen, Marco Wanderwitz, Volker Kauder, Dr. Peter Ramsauer und der Fraktion der CDU/CSU sowie der Abgeordneten Dr. h.c. Wolfgang Thierse, Monika Griefahn, Dr. Gerhard Botz, Rainer Fornahl, Gunter Weißgerber, Dr. Peter Danckert, Siegmund Ehrmann, Iris Gleicke, Wolfgang Grotthaus, Hans-Joachim Hacker, Dr. Barbara Hendricks, Klaas Hübner, Dr. h.c. Susanne Kastner, Fritz Rudolf Körper, Ernst Kranz, Angelika Krüger-Leißner, Dr. Uwe Küster, Ute Kumpf, Markus Meckel, Petra Merkel, Detlef Müller, Thomas Oppermann, Christoph Pries, Steffen Reiche (Cottbus), Michael Roth (Heringen), Renate Schmidt, Silvia Schmidt (Eisleben), Jörg Tauss, Simone Violka, Dr. Marlies Volkmer, Andrea Wicklein, Dr. Peter Struck und der Fraktion der SPD sowie der Abgeordneten Hans-Joachim Otto, Christoph Waitz, Jan Mücke, Dr. Claudia Winterstein, Jens Ackermann, Dr. Karl Addicks, Christian Ahrendt, Uwe Barth, Rainer Brüderle, Angelika Brunkhorst, Ernst Burgbacher, Patrick Döring, Jörg van Essen, Ulrike Flach, Dr. Christel Happach-Kasan, Elke Hoff, Dr. Werner Hoyer, Dr. Heinrich Leonhard Kolb, Hellmut Königshaus, Gudrun Kopp, Jürgen Koppelin, Heinz Lanfermann, Sibylle Laurischk, Harald Leibrecht, Ina Lenke, Michael Link, Patrick Meinhardt, Burkhardt Müller-Sönksen, Detlef Parr, Cornelia Pieper, Gisela Piltz, Marina Schuster, Carl-Ludwig Thiele, Florian Toncar, Dr. Volker Wissing, Hartfrid Wolff, Dr. Guido Westerwelle und der Fraktion der FDP Freiheits- und Einheitsdenkmal gestalten Der Bundestag wolle beschließen: I. Der Deutsche Bundestag stellt fest: Der Deutsche Bundestag hat in seiner Sitzung am 9. -

Antrag 16-12970

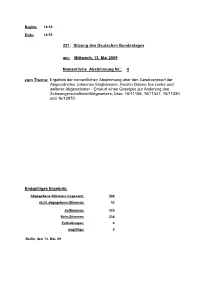

Beginn: 18:52 Ende: 18:55 221. Sitzung des Deutschen Bundestages am: Mittwoch, 13. Mai 2009 Namentliche Abstimmung Nr.: 4 zum Thema: Ergebnis der namentlichen Abstimmung über den Gesetzentwurf der Abgeordneten Johannes Singhammer, Kerstin Griese, Ina Lenke und weiterer Abgeordneter - Entwurf eines Gesetzes zur Änderung des Schwangerschaftskonfliktgesetzes; Drsn: 16/11106, 16/11347, 16/11330 und 16/12970 Endgültiges Ergebnis: Abgegebene Stimmen insgesamt: 560 nicht abgegebene-Stimmen: 52 Ja-Stimmen: 326 Nein-Stimmen: 234 Enthaltungen: 0 ungültige: 0 Berlin, den 13. Mai. 09 Seite: 1 CDU/CSU Name Ja Nein Enthaltung Ungült. Nicht abg. Ulrich Adam X Ilse Aigner X Peter Albach X Peter Altmaier X Dorothee Bär X Thomas Bareiß X Norbert Barthle X Dr. Wolf Bauer X Günter Baumann X Ernst-Reinhard Beck (Reutlingen) X Veronika Bellmann X Dr. Christoph Bergner X Otto Bernhardt X Clemens Binninger X Renate Blank X Peter Bleser X Antje Blumenthal X Dr. Maria Böhmer X Jochen Borchert X Wolfgang Börnsen (Bönstrup) X Wolfgang Bosbach X Klaus Brähmig X Michael Brand X Helmut Brandt X Dr. Ralf Brauksiepe X Monika Brüning X Georg Brunnhuber X Cajus Caesar X Gitta Connemann X Leo Dautzenberg X Hubert Deittert X Alexander Dobrindt X Thomas Dörflinger X Marie-Luise Dött X Maria Eichhorn X Dr. Stephan Eisel X Anke Eymer (Lübeck) X Ilse Falk X Dr. Hans Georg Faust X Enak Ferlemann X Ingrid Fischbach X Hartwig Fischer (Göttingen) X Dirk Fischer (Hamburg) X Axel E. Fischer (Karlsruhe-Land) X Dr. Maria Flachsbarth X Klaus-Peter Flosbach X Herbert Frankenhauser X Dr. Hans-Peter Friedrich (Hof) X Erich G. -

La Historia Del Balonmano En Chile

Universidad de Chile Instituto de la Comunicación e Imagen Escuela de Periodismo LA HISTORIA DEL BALONMANO EN CHILE MEMORIA PARA OPTAR AL TITULO DE PERIODISTA INGA SILKE FEUCHTMANN PÉREZ PROFESOR GUÍA: EDUARDO SANTA CRUZ ACHURRA Santiago, Enero de 2014 Tabla de Contenidos FUNDAMENTACIÓN 1 I. PLANTEAMIENTO DEL PROBLEMA 7 1. Problema 7 2. Objetivo Principal 7 3. Objetivos Específicos 7 4. Propósito 8 CAPITULO I MARCO CONCEPTUAL 9 I. QUÉ ES EL DEPORTE 9 1. Etimología de la palabra deporte 9 2. Definición de deporte 11 3. Historia y desarrollo del deporte 15 4. Los deportes colectivos: el balonmano 21 II. EL BALONMANO 23 1. Uso del vocablo balonmano 23 2. La naturaleza del juego 24 3. Historia del balonmano en el mundo 29 4. Estructura internacional del balonmano 36 5. Organización Panamericana 39 ii III. TRATAMIENTO DEL DEPORTE EN CHILE 45 1. Cómo se comprende el deporte en Chile 45 2. Institucionalidad deportiva en Chile 50 IV. MEDIOS DE COMUNICACIÓN DEPORTIVOS 54 1. Su relación con el balonmano 54 CAPITULO II PRIMERA ETAPA (1965-1973) 59 I. ORIGEN DEL BALONMANO EN CHILE 59 1. Los difusos y desconocidos comienzos del balonmano 59 2. La influencia alemana 61 3. De las colonias a la masificación 67 II. LOS PRIMEROS PASOS DE LA ORGANIZACIÓN NACIONAL 71 1. ¿Quién fue Pablo Botka, cuál era su plan? 71 2. El Estado y su apoyo al proyecto Botka 75 3. La experiencia escolar con el balonmano 80 III. MEDIOS DE COMUNICACIÓN 84 1. El deporte que se conoce como hándbol 84 iii CAPITULO III SEGUNDA ETAPA (1975-1990) 87 I.