CONTEMPORARY AUSTRIAN STUDIES Volume 18

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Program November 2020

View this email in your browser PROGRAM NOVEMBER 2020 Exhibition - outdoors PHOTO IS:RAEL (9.-21.11.2020, Tel Aviv) --> Stefanie Moshammer: I'll Remember to Forget Loving Art. Making Art. (12.-14.11.2020, Tel Aviv) --> Michael Kienzer: hanging around Film - digital format TLV Fest (12.-21.11.2020) --> Sangam Sharma: Another Europe --> Monja Art: Seventeen --> Gregor Schmidinger: Nevrland --> Stefan Langthaler: Fabiu Lectures & Discussion - digital format The Kelsen Legacy: Reflections upon the Centennial to the Austrian Constitution (11.11.2020) --> Prof. Clemens Jabloner, Former Vice-Chancellor of Austria, Professor for Legal Theory at the Univerity of Vienna and Director of the Hans Kelsen Institute --> Karoline Edtstadler, Austrian Federal Minister for the EU and Constitution at the Federal Chancellery When Peace Still Seemed Possible: 25th Yitzhak Rabin Memorial Day (4.11.2020) --> Maria Sterkl, correspondent of the Austrian daily Der Standard EXHIBITION OUTDOORS PHOTO IS:RAEL feat. Stefanie Moshammer (9.-21.11.2020; Tel Aviv) Ein Fixpunkt im Veranstaltungskalender Tel Avivs ist das im Herbst stattfindende Fotografiefestival PHOTO IS:RAEL. Das Festival steht dieses Jahr unter dem Motto "Transformationen" und beschreitet neue Wege. Die Ausstellungen finden im öffentlichen Raum im Freien statt und werden von einem reichhaltigen digitalen Programm begleitet. Das Festival ist erstmals als Wanderausstellung konzipiert; die Ausstellungen werden bis ins Jahr 2021 noch an weiteren Orten in Israel zu sehen sein. Aus Österreich ist die aufstrebende Foto- Künstlerin Stefanie Moshammer mit der Ausstellung I'll Remember to Forget vertreten. The photography festival PHOTO IS:RAEL, is a regular highlight on Tel Aviv's event calendar. The festival runs under the theme "transformations" and is breaking new ground. -

Interntational Covenant on Civil and Political Rights 5Th Report of The

International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights 5th Report of the Republic of Austria List of Issues Item 1: 1.1. The Covenant has the status of a federal law in the Austrian legal order. While the Covenant itself is not directly applicable, the rights enshrined therein are comprehensively protected by a number of human rights provisions which are directly applicable in Austria: Civil and political rights are protected by the Austrian Constitution itself, the European Convention on Human Rights and its Protocols (which enjoy constitutional law status in Austria) and the Charter of Fundamental Rights of the European Union (whose provisions can be invoked as constitutionally guaranteed rights in proceedings before the Austrian Constitutional Court in all cases where it is applicable). The domestic courts thus primarily refer to these human rights instruments. In addition, according to established case law of the Constitutional Court the rights protected by Austrian law, including those protected by the Austrian Constitution, must be interpreted in light of public international and, thus, also in light of the Covenant. Since the rights enshrined in the Covenant are comprehensively protected by the Austrian Constitution and the human rights instruments referred to above, both Austrian legislation and the Austrian administration always strive to ensure that full effect is given to protecting human rights within the Austrian legal order. The Austrian courts (civil and criminal courts, administrative courts and the courts of public law) are the country’s most important actors when it comes to assess the implementation of human rights obligations. The Austrian Constitutional Court plays a key role in this context as it reassesses the compliance of laws, regulations and administrative acts with constitutional standards (and, thus, essentially also the rights enshrined in the CCPR) and has the power to repeal such acts should they infringe the Constitution. -

Gesellschaft Und Psychiatrie in Österreich 1945 Bis Ca

1 VIRUS 2 3 VIRUS Beiträge zur Sozialgeschichte der Medizin 14 Schwerpunkt: Gesellschaft und Psychiatrie in Österreich 1945 bis ca. 1970 Herausgegeben von Eberhard Gabriel, Elisabeth Dietrich-Daum, Elisabeth Lobenwein und Carlos Watzka für den Verein für Sozialgeschichte der Medizin Leipziger Universitätsverlag 2016 4 Virus – Beiträge zur Sozialgeschichte der Medizin Die vom Verein für Sozialgeschichte der Medizin herausgegebene Zeitschrift versteht sich als Forum für wissenschaftliche Publikationen mit empirischem Gehalt auf dem Gebiet der Sozial- und Kulturgeschichte der Medizin, der Geschichte von Gesundheit und Krankheit sowie an- grenzender Gebiete, vornehmlich solcher mit räumlichem Bezug zur Republik Österreich, ihren Nachbarregionen sowie den Ländern der ehemaligen Habsburgermonarchie. Zudem informiert sie über die Vereinstätigkeit. Die Zeitschrift wurde 1999 begründet und erscheint jährlich. Der Virus ist eine peer-reviewte Zeitschrift und steht Wissenschaftlerinnen und Wissenschaftlern aus allen Disziplinen offen. Einreichungen für Beiträge im engeren Sinn müssen bis 31. Okto- ber, solche für alle anderen Rubriken (Projektvorstellungen, Veranstaltungs- und Aus stel lungs- be richte, Rezensionen) bis 31. Dezember eines Jahres als elektronische Dateien in der Redak- tion einlangen, um für die Begutachtung und gegebenenfalls Publikation im darauf fol genden Jahr berücksichtigt werden zu können. Nähere Informationen zur Abfassung von Bei trägen sowie aktuelle Informationen über die Vereinsaktivitäten finden Sie auf der Homepage des Ver eins (www.sozialgeschichte-medizin.org). Gerne können Sie Ihre Anfragen per Mail an uns richten: [email protected] Bibliografische Information der Deutschen Nationalbibliothek Die Deutsche Nationalbibliothek verzeichnet diese Publikation in der Deutschen Nationalbi - bli o grafie; detaillierte bibliografische Daten sind im Internet über http://dnb.d-nb.de abrufbar. Das Werk einschließlich aller seiner Teile ist urheberrechtlich geschützt. -

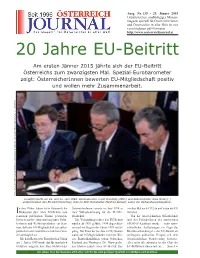

20 Jahre EU-Beitritt

Ausg. Nr. 139 • 29. Jänner 2015 Unparteiisches, unabhängiges Monats- magazin speziell für Österreicherinnen und Österreicher in aller Welt in vier verschiedenen pdf-Formaten http://www.oesterreichjournal.at 20 Jahre EU-Beitritt Am ersten Jänner 2015 jährte sich der EU-Beitritt Österreichs zum zwanzigsten Mal. Spezial-Eurobarometer zeigt: ÖsterreicherInnen bewerten EU-Mitgliedschaft positiv und wollen mehr Zusammenarbeit. Foto: Aus der ORF-Dokumentation »Menschen & Mächte. Der lange Weg nach Europa.« / metafilm EU-Gipfel Korfu am 24. und 25. Juni 1994: Bundeskanzler Franz Vranitzky (Mitte) und Außenminister Alois Mock (r.) unterschreiben den EU-Beitrittsvertrag; links im Bild: Botschafter Manfred Scheich, Leiter der Verhandlungsdelegation. n den 1980er Jahren ist in Österreich die ÖsterreicherInnen votierte im Juni 1994 in zweiten Mal nach 1972 ab und traten der EU IDiskussion über einen EG-Beitritt zum einer Volksabstimmung für die EU-Mit- nicht bei. zentralen politischen Thema geworden. gliedschaft. Von der österreichischen Öffentlichkeit Davor herrschte jahrzehntelang unter Politi- Die Verhandlungen über den EU-Beitritt und den PolitikerInnen der amtierenden kerInnen und RechtsexpertInnen ein Kon- wurden ab 1993 geführt, 1994 abgeschlos- SPÖ/ÖVP-Koalition wurde – trotz unter- sens, daß eine EG-Mitgliedschaft aus außen- sen und mit Beginn des Jahres 1995 rechts- schiedlicher Auffassungen im Zuge der politischen und neutralitätsrechtlichen Grün- gültig. Der Kreis der bis dato 12 EU-Staaten Beitrittsverhandlungen – der EU-Beitritt als den unmöglich sei. wurde auf 15 Mitgliedsländer erweitert. Wei- wichtigstes politisches Ereignis seit dem Mit dem Beitritt zur Europäischen Union tere Beitrittskandidaten waren Schweden, österreichischen Staatsvertrag bewertet. am 1. Jänner 1995 wurde das für unmöglich Finnland und Norwegen. Die NorwegerIn- Aber nicht alle stimmten in den Chor der Gehaltene möglich. -

A Hrc Wg.6 37 Aut 1 E.Pdf

United Nations A/HRC/WG.6/37/AUT/1 General Assembly Distr.: General 6 November 2020 Original: English Human Rights Council Working Group on the Universal Periodic Review Thirty-seventh session 18–29 January 2021 National report submitted in accordance with paragraph 5 of the annex to Human Rights Council resolution 16/21* Austria * The present document has been reproduced as received. Its content does not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the Secretariat of the United Nations. GE.20-14782(E) A/HRC/WG.6/37/AUT/1 I. Methodology – Approach to preparing the report1 1. The report focuses on measures implementing the recommendations accepted by Austria during the 2nd UPR. II. Implementation of the recommendations and developments since the last review2 2. Austrian courts3 are the most important actors in monitoring compliance with the Austrian Constitution. The Austrian Constitutional Court (VfGH) reviews legal norms, rescinding unconstitutional laws and unlawful regulations. This review includes compliance with constitutionally guaranteed rights, including all rights guaranteed by the European Convention on Human Rights (ECHR) and its additional protocols. Since 2012, the VfGH has also been using the EU-Charter of Fundamental Rights as a benchmark when applying European Union law. A. Protection and promotion of human rights, international level 1. International obligations, ratifications, reservations 3. To reinforce human rights protection, Austria has ratified the Protocol of 2014 to the Forced Labour Convention, 1930 since its last UPR; the Forced Labour (Supplementary Measures) Recommendation, 2014 (No. 203) was acknowledged by Parliament.4 4. The ratification of the Protocol of the Council of Europe amending the Convention for the Protection of Individuals with regard to Automatic Processing of Personal Data is currently being prepared. -

Third Reich Recycling

Herbert Kuhner Violence Under the Guise of Art or Third Reich Recycling Herbert Kuhner, the writer, is in a sense a historian. His life story runs parallel to history and illustrates that history is too serious matter to be left exclusively to bona fide historians. “In 1935, the year of his birth, the Nuremberg Laws were imposed in Germany. In 1938, when he was three years old, “The doorbell rang and I ran to the door and opened it. My mother swept me away as two men in street clothes entered. One of them, I remember clearly, wore a brown suit and limped. The other was thin and balding and wore a grey suit. They searched the apartment. The brown-suited man pushed my grandmother, who was eighty-three away from the sideboard in order to ransack it. And indeed it contained her shopping money.” (from Felled by Friendly Fire, a Memoir) 1 - Peter Malina, historian “In my view there is a Biedermeier-like silence concerning this topic. It is good that you have broken through it.”2 - Kuno Knöbl Delving Experiences I had in young years in Third-Reich Austria and returning later, has enabled me to attain a personal insight into post-war and present-day events in the land of my birth. Much has been written about the days when the Third Reich officially ceased to be, however certain facets of the aftermath and aftereffects have in my view not been brought to the fore. I could not help but delve. I wanted to get to the core and I have been gathering material over the years. -

Wolfgang Schüssel – Bundeskanzler Regierungsstil Und Führungsverhalten“

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by OTHES DIPLOMARBEIT Titel der Diplomarbeit: „Wolfgang Schüssel – Bundeskanzler Regierungsstil und Führungsverhalten“ Wahrnehmungen, Sichtweisen und Attributionen des inneren Führungszirkels der Österreichischen Volkspartei Verfasser: Mag. Martin Prikoszovich angestrebter akademischer Grad Magister der Philosophie (Mag. phil.) Wien, 2012 Studienkennzahl lt. Studienblatt: A 300 Studienrichtung lt. Studienblatt: Politikwissenschaft Betreuer: Univ.-Doz. Dr. Johann Wimmer Persönliche Erklärung Ich erkläre hiermit, dass ich die vorliegende schriftliche Arbeit selbstständig verfertigt habe und dass die verwendete Literatur bzw. die verwendeten Quellen von mir korrekt und in nachprüfbarer Weise zitiert worden sind. Mir ist bewusst, dass ich bei einem Verstoß gegen diese Regeln mit Konsequenzen zu rechnen habe. Mag. Martin Prikoszovich Wien, am __________ ______________________________ Datum Unterschrift 2 Inhaltsverzeichnis 1 Danksagung 5 2 Einleitung 6 2.1 Gegenstand der Arbeit 6 2.2. Wissenschaftliches Erkenntnisinteresse und zentrale Forschungsfrage 7 3 Politische Führung im geschichtlichen Kontext 8 3.1 Antike (Platon, Aristoteles, Demosthenes) 9 3.2 Niccolò Machiavelli 10 4 Strukturmerkmale des Regierens 10 4.1 Verhandlungs- und Wettbewerbsdemokratie 12 4.2 Konsensdemokratie/Konkordanzdemokratie/Proporzdemokratie 15 4.3 Konfliktdemokratie/Konkurrenzdemokratie 16 4.4 Kanzlerdemokratie 18 4.4.1 Bundeskanzler Deutschland vs. Bundeskanzler Österreich 18 4.4.1.1 Der österreichische Bundeskanzler 18 4.4.1.2. Der Bundeskanzler in Deutschland 19 4.5 Parteiendemokratie 21 4.6 Koalitionsdemokratie 23 4.7 Mediendemokratie 23 5 Politische Führung und Regierungsstil 26 5.1 Zusammenfassung und Ausblick 35 6 Die Österreichische Volkspartei 35 6.1 Die Struktur der ÖVP 36 6.1.1. Der Wirtschaftsbund 37 6.1.2. -

Global Austria Austria’S Place in Europe and the World

Global Austria Austria’s Place in Europe and the World Günter Bischof, Fritz Plasser (Eds.) Anton Pelinka, Alexander Smith, Guest Editors CONTEMPORARY AUSTRIAN STUDIES | Volume 20 innsbruck university press Copyright ©2011 by University of New Orleans Press, New Orleans, Louisiana, USA. All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system, without prior permission in writing from the publisher. All inquiries should be addressed to UNO Press, University of New Orleans, ED 210, 2000 Lakeshore Drive, New Orleans, LA, 70119, USA. www.unopress.org. Book design: Lindsay Maples Cover cartoon by Ironimus (1992) provided by the archives of Die Presse in Vienna and permission to publish granted by Gustav Peichl. Published in North America by Published in Europe by University of New Orleans Press Innsbruck University Press ISBN 978-1-60801-062-2 ISBN 978-3-9028112-0-2 Contemporary Austrian Studies Sponsored by the University of New Orleans and Universität Innsbruck Editors Günter Bischof, CenterAustria, University of New Orleans Fritz Plasser, Universität Innsbruck Production Editor Copy Editor Bill Lavender Lindsay Maples University of New Orleans University of New Orleans Executive Editors Klaus Frantz, Universität Innsbruck Susan Krantz, University of New Orleans Advisory Board Siegfried Beer Helmut Konrad Universität Graz Universität -

Nazi War Crimes Disclosure Act 2000 Cia Has No

CONFIDENTIAL FOU0 DOCUMENT ID: 27086969 INQNO: DOC3D 00324099 DOCNO: TEL 010178 86 PRODUCER: VIENNA SOURCE: STATE DOCTYPE: IN DOR: 19860710 TOR: 172130 DOCPREC: P 1, ORIGDATE: 198607101539 017.19. 11)11,..:1.i61:11,LCA 511:,;; MHFNO: 86 1471470 concurr,tr,cc of 0 DOCCLASS: C pKDeclass:fy CAVEATS: FOU0 EO 1295B, 25% HEADER IPS/Gil/1i: by PP RUEAIIB ZNY CCCCC ZOC STATE ZZH STU1160 PP RUEHC DE RUEHVI #0178/01 1911543 ZNY CCCCC ZZH P 101539Z JUL 86 FM AMEMBASSY VIENNA - TO RUEHC/SECSTATE WASHDC PRIORITY 5480 INFO RUFHRN/AMEMBASSY BERN 4475 RUFHOL/AMEMBASSY BONN 4537 RUFHBE/AMEMBASSY BELGRADE 8067 RUDKDA/AMEMBASSY BUDAPEST 2158 RUEHPG/AMEMBASSY PRAGUE 8765 RUFHRO/AMEMBASSY ROME 9181 RUEHOT/AMEMBASSY OTTAWA 2404 RUEHTH/AMEMBASSY ATHENS 2143 RUFHFR/AMEMBASSY PARIS 2755 RUFHLD/AMEMBASSY LONDON 0413 DECL ASSIFIED AND RELEASED BY RUFHTV/AMEMBASSY TEL AVIV 3066 RUFHMB/USDEL MBFR VIENNA 1139 CENTRAL INTELL !BENCE AGENCY BT SOURCES METHODS EXEMPT ION 392B NAZI WAR CR IMES D ISCLOSURE ACT CONTROLS DATE 2001 2007 CONFIDENTIAL LIMITED OFFICIAL USE VIENNA 10178 E.O. 12356: DECL: OADR TEXT TAGS: PREL, PGOV, AU SUBJECT: WALDHEIM: THE AFFAIR GOES ON 1. (U) INTRODUCTION AND SUMMARY: ALTHOUGH EDITORIALISTS OF AUSTRIAS CONSERVATIVE PRESS HOPED THAT THE WALDHEIM CONTROVERSY MIGHT SUBSIDE FOLLOWING THE JULY 8 NAZI WAR CRIMES DISCLOSURE ACT INAUGURATION, RECENT DEVELOPMENTS AT HOME AND TO A LESSER EXTENT ABROAD SUGGEST THE CONTRARY. PRESIDENT 2000 WALDHEIM SEEMS INTENT ON UNDERLINING HIS COMMITMENT TO BRIDGE PARTY DIVISIONS AT HOME AND SEEK RECONCILIATION CIA HAS NO OBJECTION TO DECLASSIFICATION AND/OR RELEASE OF CIA INFORMATION IN THIS DOCUMENT FOUO CONFIDENTIAL Page 1 CONFIDENTIAL . -

Austria 2019 International Religious Freedom Report

AUSTRIA 2019 INTERNATIONAL RELIGIOUS FREEDOM REPORT Executive Summary Historical and modern constitutional documents provide for freedom of religious belief and affiliation and prohibit religious discrimination. The law bans public incitement to hostile acts against religious groups and classifies registered religious groups into one of three categories: religious societies, religious confessional communities, and associations. The 16 groups recognized as religious societies receive the most benefits. Unrecognized groups may practice their religion privately if the practice is lawful and does not offend “common decency.” In May parliament banned head coverings for children in elementary schools. Authorities arrested a Christian couple for murder after they refused, for religious reasons, medical treatment for their sick child, who subsequently died. Scientologists and the Family Federation for World Peace and Unification (Unification Church) said government-funded organizations continued to advise the public against associating with them. Muslim and Jewish groups and nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) expressed concerns over what they said were the frequent and growing number of anti-Semitic and anti-Muslim acts by members of the Freedom Party (FPOe), the junior partner in the coalition government until May. According to the interior ministry, there were 49 anti-Semitic and 22 anti-Muslim incidents reported to police in 2018, the most recent year for which data were available, compared with 39 and 36 incidents, respectively, in 2017. Most incidents involved hate speech. The Islamic Faith Community (IGGIO) and the Jewish Community (IKG) have in the past reported a much higher number of incidents against their members than the interior ministry, but neither group had updated figures beyond the 540 anti-Muslim incidents the IGGIO cited in 2018 and the 503 anti-Semitic incidents the IKG reported in 2017. -

The Ends of Four Big Inflations

This PDF is a selection from an out-of-print volume from the National Bureau of Economic Research Volume Title: Inflation: Causes and Effects Volume Author/Editor: Robert E. Hall Volume Publisher: University of Chicago Press Volume ISBN: 0-226-31323-9 Volume URL: http://www.nber.org/books/hall82-1 Publication Date: 1982 Chapter Title: The Ends of Four Big Inflations Chapter Author: Thomas J. Sargent Chapter URL: http://www.nber.org/chapters/c11452 Chapter pages in book: (p. 41 - 98) The Ends of Four Big Inflations Thomas J. Sargent 2.1 Introduction Since the middle 1960s, many Western economies have experienced persistent and growing rates of inflation. Some prominent economists and statesmen have become convinced that this inflation has a stubborn, self-sustaining momentum and that either it simply is not susceptible to cure by conventional measures of monetary and fiscal restraint or, in terms of the consequent widespread and sustained unemployment, the cost of eradicating inflation by monetary and fiscal measures would be prohibitively high. It is often claimed that there is an underlying rate of inflation which responds slowly, if at all, to restrictive monetary and fiscal measures.1 Evidently, this underlying rate of inflation is the rate of inflation that firms and workers have come to expect will prevail in the future. There is momentum in this process because firms and workers supposedly form their expectations by extrapolating past rates of inflation into the future. If this is true, the years from the middle 1960s to the early 1980s have left firms and workers with a legacy of high expected rates of inflation which promise to respond only slowly, if at all, to restrictive monetary and fiscal policy actions. -

India-Austria Relations Political Relations Diplomatic Relations Between India and Austria Were Established in 1949. Traditional

India-Austria Relations Political relations Diplomatic relations between India and Austria were established in 1949. Traditionally India-Austria relations have been warm and friendly. There has been a regular exchange of high level visits between the two countries: High Level Bilateral Visits 1955 Prime Minister Pandit Nehru 1971 Prime Minister Indira Gandhi 1980 Chancellor Bruno Kreisky 1983 Prime Minister Indira Gandhi 1984 Chancellor Fred Sinowatz 1995 EAM Pranab Mukherjee 1999 President K. R. Narayanan 2005 President Heinz Fischer 2007 Foreign Minister Ursula Plassnik 2009 Speaker of Lok Sabha Meira Kumar 2010 Vice Chancellor Josef Pröll 2011 President of National Council of Austrian Parliament Barbara Prammer 2011 President Pratibha Devisingh Patil 2012 President of National Council of Austrian Parliament Barbara Prammer President of India, Pratibha Devi Singh Patil visited Austria from from 4-7 October 2011. The talks covered entire gamut of bilateral relations and international issues of mutual concern. Special emphasis was put on strengthening economic and commercial cooperation, scientific cooperation and people to people exchanges. President Fischer strongly supported India’s place in a reformed UN Security Council. He said that ‘We recognize that the world is changing fast and that the current composition in the Security Council does not reflect the realities of the new world order currently emerging. Your country deserves to play a bigger role in the Security Council’. Austrian Federal President Dr. Heinz Fischer visited India in February 2005. The Joint Statement issued during the visit highlighted the need to keep up the momentum of exchanging high level visits, expanding and deepening cooperation in power, environment, health infrastructure, biotechnology, information technology, engineering and transport, intensifying cooperation between universities and research institutions, expanding direct air- links between the two countries, condemning terrorism and a dialogue on UN related issues.