Forced Labor in Austria Late Recognition History Tragic Fates

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Abschnittsfeuerwehrkommando St.Pölten - Ost | 3071 Böheimkirchen Url Homepage: | Email (System): [email protected]

Abschnittsfeuerwehrkommando St.Pölten - Ost | 3071 Böheimkirchen Url Homepage: http://www.afkdo-plost.at/ | EMail (System): [email protected] vorläufige Ergebnisliste (Stand: 09.06.2019 12:30) Abschnittsfeuerwehrleistungsbewerb 09.06.2019 - 09.06.2019 AFKDO St.Pölten - Ost Rang Gruppenname Instanz AFKDO Nr. Gesamt Bronze o Alterspunkte / Eigene 1 Stössing Stössing St.Pölten - Ost 4 404,13 2 Untergrafendorf Untergrafendorf St.Pölten - Ost 5 403,38 3 Böheimkirchen-Mechters Böheimkirchen-Mechters St.Pölten - Ost 12 394,14 4 Kasten Kasten St.Pölten - Ost 2 379,13 5 Fahrafeld Fahrafeld St.Pölten - Ost 3 378,26 6 Pyhra-Ober Tiefenbach Pyhra-Ober Tiefenbach St.Pölten - Ost 49 372,14 7 Böheimkirchen Ausserkasten-Furth Böheimkirchen Ausserkasten-Furth St.Pölten - Ost 11 359,69 8 Böheimkirchen-Markt Böheimkirchen-Markt St.Pölten - Ost 7 356,74 9 Pyhra-Perersdorf Pyhra-Perersdorf St.Pölten - Ost 13 354,37 10 Michelbach Michelbach St.Pölten - Ost 1 341,32 Bronze mit Alterspunkte / Eigene 1 Wald Wald St.Pölten - Ost 8 379,39 Silber o Alterspunkte / Eigene 1 Fahrafeld Fahrafeld St.Pölten - Ost 20 385,70 2 Untergrafendorf Untergrafendorf St.Pölten - Ost 29 384,65 3 Stössing Stössing St.Pölten - Ost 23 377,96 4 Pyhra-Ober Tiefenbach Pyhra-Ober Tiefenbach St.Pölten - Ost 55 373,21 5 Kasten Kasten St.Pölten - Ost 22 362,16 6 Böheimkirchen-Mechters Böheimkirchen-Mechters St.Pölten - Ost 28 344,82 7 Michelbach Michelbach St.Pölten - Ost 21 339,26 Bronze o Alterspunkte / Abschnitt 1 Karlstetten Karlstetten St.Pölten - West 42 385,84 2 Haunoldstein 1 Haunoldstein -

Feuerwehr Aktuell

Freiwillige Feuerwehr Euratsfeld Wassergasse 27 71. Ausgabe 3324 Euratsfeld 23. Februar 2012 FEUERWEHR AKTUELL Einteilungen Termine Impfaktion Ausbildungsplan Kdt. Rudolf Katzengruber 1. Kdt. Stv. Leopold Winkler 2. Kdt. Stv. Maximilian Pruckner 1. Zkdt 2. Zkdt 3. Zkdt Gottfried Distelberger Helmut Mille Anton Wagner 1. Gkdt 2. Gkdt 3. Gkdt 4. Gkdt 5. Gkdt 6. Gkdt Koblinger J. Demel Al. Zeilhofer M. Steindl R. Lueger M. Distelberger M. Leiter des Verwaltungsdienst: Stadlbauer Bruno SB-AS: Mille Helmut Stv. LdV. Gassner Christian SB-Funk: Wagner Anton Gehilfe des LdV: Lautzky Johann SB-EDV: Steindl Rene Ausbilder: Hochholzer Gerald SB-Wasserdienst: Zeilhofer Martin FW. Arzt: Dr. Franz Josef Gabler SB-FMD: Groiss Peter Fahrmeister: Krammer Herbert SB-Schadstoff: Zehetgruber Roland Fahrmeister Gehilfe: Krammer Stefan Ordnerdienst: Wieser Josef Zeugmeister: Demel Anton Hausmeister: Mittergeber Roman Zeugmeister Gehilfe: Schlemmer Alfred 1. Zugtruppkdt.: Zeilinger Ch. FJ: Dr. Franz Alois Gabler, Katzengruber Michael, Prigl Reinhard, Vanek Christian Festobmann: Zeilinger Ch, Gassner Ch, Pruckner M Einsatzleiter • BR Rudolf Katzengruber • OBI Leopold Winkler • OBI Maximilian Pruckner • 1 Zkdt. OBM Gottfried Distelberger • 2 Zkdt. OBM Helmut Mille • Ausbildner OBM Gerald Hochholzer • 3 Zkdt. BM Anton Wagner • FA Dr. Franz Alois Gabler • ELFA Stv. Dr. Franz Josef Gabler • OLM Christian Zeilinger • ASB Johann Koblinger • V Christian Gassner • HVM Johann Lautzky • OLM Matthias Lueger • OLM Rene Steindl • OLM Alfred Demel • BM Anton Demel • BM Herbert Krammer • LM Martin Zeilhofer • LM Matthias Distelberger Wenn von allen angeführten Personen, keiner anwesend ist, ist immer derjenige Einsatzleiter, der den höheren Dienstgrad hat. Bei gleichem Dienstgrad, ist entscheidend, wer diesen schon länger trägt. Euratsfeld im Jänner 2012 Termine 2012 Jänner 06.01. -

NÖ Statistisches Handbuch 2017

NÖ Landesstatistik Statistisches Handbuch Eine Servicestelle des Landes Niederösterreich des Landes Niederösterreich 41 Auskunfts- und Servicestelle Informationen nach Verfügbarkeit für alle Interessierten 41. Jahrgang 2017 Projektarbeit Beratung, Mitarbeit und Durchführung Datenauswertung Auf Anfrage und projektbezogen Statistische Erhebungen Im Interesse des Landes Niederösterreich Kontakt Amt der NÖ Landesregierung Gruppe Raumordnung, Umwelt und Verkehr Abteilung Raumordnung und Regionalpolitik – Statistik Landhausplatz 1 3109 St. Pölten E-Mail: [email protected] Tel.: 02742 9005-14241 2 1 5 NÖ Statistisches Handbuch 2017 Statistisches Handbuch des Landes Niederösterreich 41. Jahrgang 2017 1| 215 2 Bezirkstabellen und -grafiken ohne Wien-Umgebung beziehen sich auf den ab 1. 1. 2017 gültigen Gebietsstand (LGBl. Nr. 4/2016), jene mit Werten für Wien-Umgebung auf den bis 31. 12. 2016 gültigen. Datenstände vor 2017 wurden nach Möglichkeit umgerechnet, Sonderfälle sind gekennzeichnet. Falls nicht ausdrücklich anders angegeben, beziehen sich die Tabellen in diesem Handbuch ausschließlich auf das Bundesland Niederösterreich. Die enthaltenen Daten, Tabellen und Grafiken sind urheberrechtlich geschützt. Trotz sorgfältiger Prüfung des Inhalts kann für Richtigkeit, Vollständigkeit, Aktualität und Qualität der in dieser Publikation enthaltenen Informationen keine Gewähr übernommen werden. NÖ Schriften 215 – Information Amt der Niederösterreichischen Landesregierung Für den Inhalt verantwortlich: Mag. Markus Hemetsberger Abteilung Raumordung und Regionalpolitik – Statistik Datenkonvertierung: Laudenbach, 1070 Wien Druck: Druckerei Haider Manuel e. U., 4274 Schönau i. M. Erschienen im Oktober 2017 ISBN 978-3-85006-215-2 3 Vorwort Dynamische Entwicklung und Mut zu Innovation sind zwei wesentliche Eck- pfeiler einer erfolgreichen Landesentwicklung. Um diesen Erfolg auch stetig weiterführen zu können, braucht es eine Art Kontrollinstanz, die in regelmäßigen Abständen die Entwicklung des Bundeslandes aus unterschiedlichen Blick- winkeln beleuchtet. -

Program November 2020

View this email in your browser PROGRAM NOVEMBER 2020 Exhibition - outdoors PHOTO IS:RAEL (9.-21.11.2020, Tel Aviv) --> Stefanie Moshammer: I'll Remember to Forget Loving Art. Making Art. (12.-14.11.2020, Tel Aviv) --> Michael Kienzer: hanging around Film - digital format TLV Fest (12.-21.11.2020) --> Sangam Sharma: Another Europe --> Monja Art: Seventeen --> Gregor Schmidinger: Nevrland --> Stefan Langthaler: Fabiu Lectures & Discussion - digital format The Kelsen Legacy: Reflections upon the Centennial to the Austrian Constitution (11.11.2020) --> Prof. Clemens Jabloner, Former Vice-Chancellor of Austria, Professor for Legal Theory at the Univerity of Vienna and Director of the Hans Kelsen Institute --> Karoline Edtstadler, Austrian Federal Minister for the EU and Constitution at the Federal Chancellery When Peace Still Seemed Possible: 25th Yitzhak Rabin Memorial Day (4.11.2020) --> Maria Sterkl, correspondent of the Austrian daily Der Standard EXHIBITION OUTDOORS PHOTO IS:RAEL feat. Stefanie Moshammer (9.-21.11.2020; Tel Aviv) Ein Fixpunkt im Veranstaltungskalender Tel Avivs ist das im Herbst stattfindende Fotografiefestival PHOTO IS:RAEL. Das Festival steht dieses Jahr unter dem Motto "Transformationen" und beschreitet neue Wege. Die Ausstellungen finden im öffentlichen Raum im Freien statt und werden von einem reichhaltigen digitalen Programm begleitet. Das Festival ist erstmals als Wanderausstellung konzipiert; die Ausstellungen werden bis ins Jahr 2021 noch an weiteren Orten in Israel zu sehen sein. Aus Österreich ist die aufstrebende Foto- Künstlerin Stefanie Moshammer mit der Ausstellung I'll Remember to Forget vertreten. The photography festival PHOTO IS:RAEL, is a regular highlight on Tel Aviv's event calendar. The festival runs under the theme "transformations" and is breaking new ground. -

Stories of Capitalism: Inside the Role of Financial Analysts

Stories of Capitalism Stories of Capitalism InsIde the Role of fInancIal analysts Stefan Leins The University of Chicago Press Chicago and London publication of this book has been aided by grants from the bevington fund and the swiss national science foundation. This work is being made available under the Creative Commons Attribution-Non-Commercial-No Derivatives 4.0 International License (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0). To view a copy of this license, visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ The University of Chicago Press, Chicago 60637 The University of Chicago Press, Ltd., London © 2018 by The University of Chicago All rights reserved. No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission, except in the case of brief quotations in critical articles and reviews. For more information, contact the University of Chicago Press, 1427 East 60th Street, Chicago, IL 60637. Published 2018 Printed in the United States of America 27 26 25 24 23 22 21 20 19 18 1 2 3 4 5 ISBN-13: 978-0-226-52339-2 (cloth) ISBN-13: 978-0-226-52342-2 (paper) ISBN-13: 978-0-226-52356-9 (e- book) DOI: 10.7208/chicago/9780226523569.001.0001 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Names: Leins, Stefan, author. Title: Stories of capitalism : inside the role of financial analysts / Stefan Leins. Description: Chicago ; London : The University of Chicago Press, 2018. | Includes bibliographical references and index. Identifiers: LCCN 2017031750 | ISBN 9780226523392 (cloth : alk. paper) | ISBN 9780226523422 (pbk. : alk. paper) | ISBN 9780226523569 (e-book) Subjects: LCSH: Financial analysts | Financial services industry—Employees. -

VIA LATINA 22 # 281 - June 2019 News from the General Administration of the Society of Mary

VIA LATINA 22 # 281 - June 2019 News from the General Administration of the Society of Mary Institution of new lectors and acolytes at the Marianist International Seminary in Rome Left - Right. First row (from above): Bro. Renny Markose, SM (IN), Fr. Francisco Canseco, SM (ES), Rector of the Intl Seminary, Bro. Peter Heiskell, SM (US), Fr. André Fétis, SM (FR), Superior General, Fr. Pablo Rambaud, SM (ES), General Assistant for Religi ous Life and Bro. Lester Kaehler, SM (US), Vice - Rector of the Intl Seminary. Second row: Bro. Brandon Paluch, SM (US), Bro. Michael Chiuri, SM (US), Bro. David Kangwa, SM (EA) and Bro. Santhosh Savarimuthu, SM (IN). Third row: Fr. Antonio Gascón, SM (ES), Archivist and Postulator General, Bro. Elie Oka, SM (IV), Bro. Alejandro Borrella, SM (ES), Bro. Victor Ferreira de Aguiar, SM (ES - Brazil) and Bro. Cyprian Maingi, SM (EA). On Monday, May 27, five of our brothers from the Chaminade International Seminary in Rome were installed as lectors and four were installed as acolytes. The new lectors are: Alejandro Borella (ES), Victor Ferreira de Aguiar (ES), David Kangwa (EA), Cypria n Maingi (EA), and Santosh Savarimuthu (IN). The new Acolytes are: Michael Chiuri (USA), Renny Markose (IN), Elie Kouakou Oka (IV), and Brandon Paluch (USA). The ceremony, presided over by the Superior General, took place during the Eucharist on Monday evening. As a matter of common practice, the Seminary Community and the General Administration community participate together in the Monday evening Eucharist. The evening ended with a festive meal enjoyed by both communities together. On the path to the priesthood, these ministries are the occasion for each seminarian to become more deeply aware of the role of the Word of God and the Eucharist in their lives. -

Juli / August 2021 Dank Des Präsidenten

Juli / August 2021 Dank des Präsidenten Liebe Hörerfamilie Es ist mir ein besonderes Anliegen, mich persönlich an Sie zu wenden. Denn heute möchten wir unserem Programm- direktor Andreas Schätzle Danke sagen. Mit Ende August übergibt er die „Fackel des Programmdirektors“ seinem Nach- folger Br. Peter Ackermann. Über sechzehn Jahre hat Andreas Schätzle als Missionar sein Priestertum, seine Liebe zur Gottesmutter, sein Wissen, Können und all seine Kraft Radio Maria zur Verfügung gestellt. Missionarisch und mit Leidenschaft diente er dem Radio der Gottesmutter, um allen Menschen an allen Orten das Evangelium zu verkünden. Sein Primizspruch ist: „Feuer auf die Erde zu werfen, bin ich gekommen – wie froh wäre ich, es würde schon brennen“ (Lk 12,49) – in dieser Dynamik des Heiligen Geistes hat er - gewissermaßen als „Pfarrer der größten Pfarre Österreichs“ – Radio Maria geleitet. Auch von den Verantwortlichen in der Weltfamilie wird mit Dankbarkeit festgestellt, dass das Wirken von Programmdirektor Andreas Schätzle ganz wesentlich die Verbreitung und Annahme des Radios durch Sie, geschätzte Hörerinnen und Hörer, vorangebracht hat. Lieber Andreas, Danke, dass Du uns alle, mich als Präsident seit über 13 Jahren, die Mitglieder des Vereines, den Vorstand, die haupt- und ehrenamtlichen Mitarbeiterinnen und Mitarbeiter sowie die Referentinnen und Referenten on Air mit Deinem missiona- rischen Feuer entzündet, geführt und begleitet hast. Deine Berufung zum interimistischen Programmdirektor für Radio Maria England zeigt auch, wie sehr Dein Wirken weit über das österreichische Radio Maria hinaus wahrgenommen und geschätzt wird. Für die wichtige und vertrauensvolle Aufgabe in der Weltfamilie und für Dich persönlich als Priester & Musiker alles Gute, Gottes reichen Segen! Wir vertrauen Dich besonders der Fürsprache der Muttergottes an. -

Stadterhebungsfeier Mit LH Dr. Erwin Pröll

www.vp-pressbaum.at der pressbaum Die Gemeindeinformation der Volkspartei Pressbaum Ausgabe Nr. 32 März 2013Zul.Nr. 38188W72U 1/13 Ampelregelung für Aura-Kreuzung Laut Bgm Josef Schmidl-Haberleitner böte sich aber nun die Gelegenheit, eine neue Ampelanlage für den gesamten Kreuzungs- bereich zu installieren. Mehr davon auf Seite 17 Heinz Strobl alias „Gandalf“ ausgezeichnet Landeshauptmann Dr. Erwin Pröll überreicht Bürgermeister Josef Schmidl-Haberleitner die Stadternennungs-Urkunde Stadterhebungsfeier mit Bürgermeister Josef Schmidl-Haberleitner LH Dr. Erwin Pröll und Stadträtin Irene Wallner-Hofhansl über- reichten dem international anerkannten Mu- Nachdem bereits am 4. Oktober 2012 Pressbaum in einer Sitzung des siker „Gandalf“ das „Goldene Ehrenzeichen“ Niederösterreichischen Landtages mit den Stimmen aller im Landtag ver- der Stadtgemeinde Pressbaum. tretenen Parteien zur Stadt erhoben wurde, fand am Sonntag dem 17. Fe- Mehr davon auf Seite 19 bruar 2013, im Sacré Coeur Pressbaum die offizielle Stadterhebungsfeier und die Überreichung der Stadterhebungsurkunde durch den niederöster- Kindergarten II reichischen Landeshauptmann, Dr. Erwin Pröll, an Bürgermeister Josef besucht Senecura Schmidl-Haberleitner statt. Mehr davon auf Seite 4 Pressbaumer Die Sternsinger der Pfarre Faschingszug Pressbaum Am Fasching-Sonntag um 10.30 Uhr star- Junge Mädchen und Buben, die trotz tete bei Schneegestöber und Kälte der Kälte und Schnee auch heuer wieder als Es ist nun schon Tradition, dass in den Faschingszug vom Billa-Parkplatz in Tull- Sternsinger unterwegs waren um den Tagen vor Weihnachten die Kinder eines nerbach und zog auf der Bundesstraße Menschen Gottes Segen zu bringen, ha- Pressbaumer Kindergartens die alten Senio- bis zum Pressbaumer Kirchenplatz. ben wieder ein schönes Ergebnis erzielt. rinnen und Senioren im Sozialzentrum Sene- Cura besuchen. -

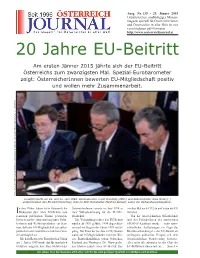

20 Jahre EU-Beitritt

Ausg. Nr. 139 • 29. Jänner 2015 Unparteiisches, unabhängiges Monats- magazin speziell für Österreicherinnen und Österreicher in aller Welt in vier verschiedenen pdf-Formaten http://www.oesterreichjournal.at 20 Jahre EU-Beitritt Am ersten Jänner 2015 jährte sich der EU-Beitritt Österreichs zum zwanzigsten Mal. Spezial-Eurobarometer zeigt: ÖsterreicherInnen bewerten EU-Mitgliedschaft positiv und wollen mehr Zusammenarbeit. Foto: Aus der ORF-Dokumentation »Menschen & Mächte. Der lange Weg nach Europa.« / metafilm EU-Gipfel Korfu am 24. und 25. Juni 1994: Bundeskanzler Franz Vranitzky (Mitte) und Außenminister Alois Mock (r.) unterschreiben den EU-Beitrittsvertrag; links im Bild: Botschafter Manfred Scheich, Leiter der Verhandlungsdelegation. n den 1980er Jahren ist in Österreich die ÖsterreicherInnen votierte im Juni 1994 in zweiten Mal nach 1972 ab und traten der EU IDiskussion über einen EG-Beitritt zum einer Volksabstimmung für die EU-Mit- nicht bei. zentralen politischen Thema geworden. gliedschaft. Von der österreichischen Öffentlichkeit Davor herrschte jahrzehntelang unter Politi- Die Verhandlungen über den EU-Beitritt und den PolitikerInnen der amtierenden kerInnen und RechtsexpertInnen ein Kon- wurden ab 1993 geführt, 1994 abgeschlos- SPÖ/ÖVP-Koalition wurde – trotz unter- sens, daß eine EG-Mitgliedschaft aus außen- sen und mit Beginn des Jahres 1995 rechts- schiedlicher Auffassungen im Zuge der politischen und neutralitätsrechtlichen Grün- gültig. Der Kreis der bis dato 12 EU-Staaten Beitrittsverhandlungen – der EU-Beitritt als den unmöglich sei. wurde auf 15 Mitgliedsländer erweitert. Wei- wichtigstes politisches Ereignis seit dem Mit dem Beitritt zur Europäischen Union tere Beitrittskandidaten waren Schweden, österreichischen Staatsvertrag bewertet. am 1. Jänner 1995 wurde das für unmöglich Finnland und Norwegen. Die NorwegerIn- Aber nicht alle stimmten in den Chor der Gehaltene möglich. -

Ein Beitrag Zur Kenntnis Der Molluskenfauna Österreichs

ZOBODAT - www.zobodat.at Zoologisch-Botanische Datenbank/Zoological-Botanical Database Digitale Literatur/Digital Literature Zeitschrift/Journal: Jahrbuch für Landeskunde von Niederösterreich Jahr/Year: 1990 Band/Volume: 54-55 Autor(en)/Author(s): Frank Christina Artikel/Article: Ein Beitrag zur Kenntnis der Molluskenfauna Österreichs 85- 144 ©Verein für Landeskunde von Niederösterreich;download http://www.noe.gv.at/noe/LandeskundlicheForschung/Verein_Landeskunde.html Ein Beitrag zur Kenntnis der Molluskenfauna Österreichs Zusammenfassung der Sammeldaten aus Salzburg, Oberösterreich, Niederösterreich, Steiermark, Burgenland und Kärnten (1965-1987) Von Christina Frank Mit dem Catalogus Faunae Austriae (1960), vor allem aber mit dem großen Kar tenwerk von Klemm (1974) wurde ein wesentlicher Grundstein in der Erfor schung der rezenten Molluskenfauna Österreichs gesetzt. Diese umfassende Dar stellung der Verbreitung der Gehäuseschnecken wurde seit ihrem Erscheinen in verschiedener Weise ergänzt. Neben der Beschreibung von Lokalfaunen, Erst fundberichten und Neubeschreibungen, die hier nicht einzeln zitiert werden kön nen, erschienen die Arbeiten von Frank (1986) und Reischütz (1981, Wasser schnecken, und 1986b, Nacktschnecken)*). Die vorliegende Bearbeitung von über 160 Standorten aus Salzburg, Oberöster reich, Niederösterreich, Steiermark, Burgenland und Kärnten ist als eine Ergän zung zu Frank (1975-1987) gedacht. Die Aufsammlungen ergaben 173 Arten terre strischer und aquatischer Mollusken (inklusive Unterarten, Rassen und Formen); sie erfolgten stets qualitativ. Jede der alphabetisch geordneten Fundstellen wird durch Angabe des Bundes landes, der geographischen Lagebeziehung zu einer in der Nähe befindlichen, größeren Stadt und der Höhe präzisiert. In den meisten Fällen wird auch eine kurze Standortbeschreibung gegeben. Die festgestellten Molluskenarten sind, wenn möglich, mit den deutschen Namen versehen. Die Nomenklatur folgt Kerney et al. (1983): Landschnecken; Reischütz (1986b): Nacktschnecken, Richnovszky & Pinter (1979), und Frank u. -

Fagan Edward R., Ed. Teacher Education: Reflection and Change

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 330 647 SP 032 935 AUTHOR Dupuis, Mary M., Ed.; Fagan Edward R., Ed. TITLE Teacher Education: Reflection and Change. Monograph 5. INSTITUTION Pennsylvania State Univ., University Park. Div. of Curriculum and Instruction. PUB DATE Nov 90 NOTE 142p. PUB TYPE Collected Works - General (020) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC06 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS American Indians; Beginning Teacher Induction; Biculturalism; Cognitive Style; Computer Assisted Instruction; Cooperative Learning; *Educational Change; Elementary Secondary Education; Field Experience Programs; Higher Education; *Preservice Teacher Education; Reading Processes; Staff Development; *Teacher Education Curriculum; *Teacher Education Programs ABSTRACT The papers in this monograph represent responses to criticisms of teacher education. The theme connecting the papers is reflection and change in teacher education. The followingpapers are included:(1) "Computers in Education--Another Failed Technolo y?" (Thomas A. Drazdowski);(2) "Selected Effects of Cooperative Learning" (Therese A. Ream); (3) "Teaching the Reading Processto Elementary Education Majors: Issues to Consider" (Michele L. Irvin); (4) "Field Experiences To Bridge the Gap Between Theory andPractice" (Michele Tellep); (5) "Bicultural Teacher Education: A Native American Perspective" (Doris McGrady);(6) "Whole Brain Learning, Learning Styles and Implications on Teacher Education" (Phillip V. Shortman);(7) "Expert Teachers as Guest Lecturers for Preservice Teachers: An Organizational Proposal" (Robert Clemens);(8) "New -

Associate Professor, Department of History

Matthew Paul Berg Professor, Department of History John Carroll University 1 John Carroll Boulevard University Heights, Ohio 44118 Office 216.397.4763 Fax: 216.397.4175 E-mail: [email protected] Education Ph.D. University of Chicago 1993 M.A. University of Chicago 1985 B.A. University of California, Los Angeles 1984 Additional Training January 2009. Center for Advanced Holocaust Studies Hess Seminar, “The Holocaust and other Genocides,” USHMM, Washington DC. 2002-2003. Participant, Association of American Colleges & Universities Workshop “The Liberal Education and Global Citizenship: The Arts of Democracy.” June 2002. United Nations International Conflict Research Seminar “Dealing with the Past.” University of Ulster/Magee Campus, Derry, Northern Ireland. January 2002. Center for Advanced Holocaust Studies Hess Seminar “The Concentration Camp System,” USHMM, Washington DC. July 2002. “Summer Academy on the OSCE.” Austrian Study Center for Peace and Conflict Resolution Schlaining, Austria. June 2000. “Foundation Course, International Civilian Peace-Keeping and Peace-Building.” Austrian Study Center for Peace and Conflict Resolution, Schlaining, Austria. Teaching Experience 2008 – Professor of History, John Carroll University 2000 – 2008 Associate Professor, Department of History, John Carroll University 1994 – 2000 Assistant Professor, Department of History, John Carroll University 1993 – 1994 Visiting Assistant Professor, Department of History, University of Toledo 1991 – 1993 Lecturer, Social Sciences Collegiate Division and Department of History, University of Chicago Berg, CurriculumVitae, 1 Matthew Paul Berg Courses Taught •First Year Seminar. •Introduction to Human Rights. •World Civilizations to 1600 / World Civilizations since 1600. •20th Century Global History. •World War One and Modernity. •The Cold War. •Justice & Democracy in a Global Context. •History as Art & Science (departmental methods course).