Dbb02c0a3e11b65a87e51d1c44

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

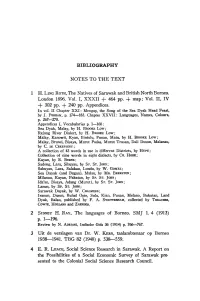

BIBLIOGRAPHY NOTES to the TEXT 1 H. LING ROTH, the Natives

BIBLIOGRAPHY NOTES TO THE TEXT 1 H. LING ROTH, The Natives of Sarawak and British North Borneo. London 18%. Vol. I, XXXII + 464 pp. + map; Vol. II, IV + 302 pp. + 240 pp. Appendices. In vol. II Chapter XXI: Mengap, the Song of the Sea Dyak Head Feast, by J. PERHAM, p. 174-183. Chapter XXVII: Languages, Names, Colours, p.267-278. Appendices I, Vocabularies p. 1-160: Sea Dyak, Malay, by H. BROOKE Low; Rejang River Dialect, by H. BROOKE Low; Malay, Kanowit, Kyan, Bintulu, Punan, Matu, by H. BROOKE Low; Malay, Brunei, Bisaya, Murut Padas, Murut Trusan, Dali Dusun, Malanau, by C. DE CRESPIGNY; A collection of 43 words in use in different Districts, by HUPE; Collection of nine words in eight dialects, by CH. HOSE; Kayan, by R. BURNS; Sadong, Lara, Sibuyau, by SP. ST. JOHN; Sabuyau, Lara, Salakau, Lundu, by W. GoMEZ; Sea Dayak (and Bugau), Malau, by MR. BRERETON; Milanau, Kayan, Pakatan, by SP. ST. JOHN; Ida'an, Bisaya, Adang (Murut), by SP. ST. JOlIN; Lanun, by SP. ST. JOHN; Sarawak Dayak, by W. CHALMERS; Iranun, Dusun, Bulud Opie, Sulu, Kian, Punan, Melano, Bukutan, Land Dyak, Balau, published by F. A. SWETTENHAM, collected by TREACHER, COWIE, HOLLAND and ZAENDER. 2 SIDNEY H. RAY, The languages of Borneo. SMJ 1. 4 (1913) p.1-1%. Review by N. ADRIANI, Indische Gids 36 (1914) p. 766-767. 3 Uit de verslagen van Dr. W. KERN, taalambtenaar op Borneo 1938-1941. TBG 82 (1948) p. 538---559. 4 E. R. LEACH, Social Science Research in Sarawak. A Report on the Possibilities of a Social Economic Survey of Sarawak pre sented to the Colonial Social Science Research Council. -

Of ODOARDOBECCARI Dedication

1864 1906 1918 Dedicated to the memory of ODOARDOBECCARI Dedication A dedication to ODOARDO BECCARI, the greatest botanist ever to study in Malesia, is long overdue. Although best known as a plant taxonomist, his versatile genius extended far beyond the basic field ofthis branch ofBotany, his wide interest leading him to investigate the laws ofevolution, the interrelations between plants and animals, the connection between vegetation and environ- cultivated ment, plant distribution, the and useful plants of Malesia and many other problems of life. plant But, even if he devoted his studies to plants, in the depth of his mind he was primarily a naturalist, and in his long, lonely and dangerousexplorations in Malesia he was attracted to all aspects ofnature and human life, assembling, besides plants, an incredibly large number of collec- tions and an invaluable wealth ofdrawings and observations in zoology, anthropologyand ethnol- He ogy. was indeed a naturalist, and one of the greatest of his time; but never in his mind were the knowledge and beauty of Nature disjoined, and, as he was a true and complete naturalist, he the time was at same a poet and an artist. His Nelleforestedi Borneo, Viaggi ericerche di un mturalista(1902), excellently translatedinto English (in a somewhatabbreviated form) by Prof. E. GioLiouandrevised and edited by F.H.H. Guillemardas Wanderingsin the great forests of Borneo (1904), is a treasure in tropical botany; it is in fact an unrivalledintroductionto tropical plant lifeand animals, man included. It is a most readable book touching on all sorts of topics and we advise it to be studied by all young people whose ambition it is to devote their life to tropical research. -

Learn Thai Language in Malaysia

Learn thai language in malaysia Continue Learning in Japan - Shinjuku Japan Language Research Institute in Japan Briefing Workshop is back. This time we are with Shinjuku of the Japanese Language Institute (SNG) to give a briefing for our students, on learning Japanese in Japan.You will not only learn the language, but you will ... Or nearby, the Thailand- Malaysia border. Almost one million Thai Muslims live in this subregion, which is a belief, and learn how, to grow other (besides rice) crops for which there is a good market; Thai, this term literally means visitor, ASEAN identity, are we there yet? Poll by Thai Tertiary Students ' Sociolinguistic. Views on the ASEAN community. Nussara Waddsorn. The Assumption University usually introduces and offers as a mandatory optional or free optional foreign language course in the state-higher Japanese, German, Spanish and Thai languages of Malaysia. In what part students find it easy or difficult to learn, taking Mandarin READING HABITS AND ATTITUDES OF THAI L2 STUDENTS from MICHAEL JOHN STRAUSS, presented partly to meet the requirements for the degree MASTER OF ARTS (TESOL) I was able to learn Thai with Sukothai, where you can learn a lot about the deep history of Thailand and culture. Be sure to read the guide and learn a little about the story before you go. Also consider visiting neighboring countries like Cambodia, Vietnam and Malaysia. Air LANGUAGE: Thai, English, Bangkok TYPE OF GOVERNMENT: Constitutional Monarchy CURRENCY: Bath (THB) TIME ZONE: GMT No 7 Thailand invites you to escape into a world of exotic enchantment and excitement, from the Malaysian peninsula. -

Oral and Written Traditions of Buginese: Interpretation Writing Using the Buginese Language in South Sulawesi

Volume-23 Issue-4 ORAL AND WRITTEN TRADITIONS OF BUGINESE: INTERPRETATION WRITING USING THE BUGINESE LANGUAGE IN SOUTH SULAWESI 1Muhammad Yusuf, 2Ismail Suardi Wekke Abstract---The uniqueness of the Buginese tribe is in the form of its oral and written traditions that go hand in hand. Oral tradition is supported by the Lontarak Manuscript which consists of Lontarak Pasang, Attoriolong, and Pau-pau ri Kadong. On the other hand, the Buginese society has the Lontarak script, which supports the written tradition. Both of them support the transmission of the knowledge of the Buginese scholars orally and in writing. This study would review the written tradition of Buginese scholars who produce works in the forms of interpretations using the Buginese language. They have many works in bequeathing their knowledge, which is loaded with local characters, including the substance and medium of the language. The embryonic interpretation began with the translation works and rubrics. Its development can be divided based on the characteristics and the period of its emergence. The First Period (1945 – 1960s) was marked by copying interpretations from the results of scholars’ reading. The Second Period (the mid-1960s – 1980s) was marked by the presence of footnotes as needed, translations per word, simple indexes, and complete interpretations with translations and comments. The Third Period (the 1980s – 2000s) started by the use of Indonesian and Arabic languages and the maintenance and development of local interpretations in Buginese, Makassarese, Tator, and Mandar. The scholar adapts this development while maintaining local treasures. Keywords---Tradition, Buginese, Scholar, Interpretation, Lontarak I. Introduction Each tribe has its characteristics and uniqueness as the destiny of life and ‘Divine design’ (sunnatullah) (Q.s. -

BAHASA TIDUNG PULAU SEBATIK: SATU TINJAUAN DINI the Sebatik Island Tidung Language: a Preliminary View

MANU Bil. 30, 79-102, 2019 (Disember) E-ISSN 2590-4086© Saidatul Nornis Hj. Mahali BAHASA TIDUNG PULAU SEBATIK: SATU TINJAUAN DINI The Sebatik Island Tidung Language: A Preliminary View SAIDATUL NORNIS HJ. MAHALI Pusat Penyelidikan Pulau-Pulau Kecil, Universiti Malaysia Sabah, 88400 Kota Kinabalu, Sabah [email protected] Dihantar: 19 November 2018 / Diterima: 14 Mac 2019 Abstrak Bahasa Tidung merupakan salah satu bahasa yang dituturkan di Sabah. Memandangkan belum ada sebarang tulisan yang memerihalkan bahasa Tidung Sabah, maka perbincangan dalam makalah ini hanya akan memfokuskan tentang inventori fonem dan leksikal asas bahasa Tidung. Data bahasa Tidung dalam perbincangan ini merupakan hasil kerja lapangan di Pulau Sebatik, Tawau. Pulau Sebatik boleh dihubungi dari jeti di Bandar Tawau ke jeti di Kampung Bergosong dengan masa perjalanan sekitar 15 ke 20 minit. Pulau ini didominasi oleh orang-orang Bugis, Tidung dan Bajau yang menjadikan laut sebagai salah satu sumber kehidupan mereka. Perbincangan dalam makalah ini merupakan hasil kerja lapangan di Pulau Sebatik yang menggunakan kaedah temu bual dan pemerhatian ikut serta. Seramai 20 orang informan telah ditemu bual untuk mendapatkan gambaran umum tentang bahasa Tidung di pulau itu. Namun, hanya dua orang responden khusus ditemu bual untuk mendapatkan data asas bahasa Tidung. Kedua-dua responden itu dipilih kerana mereka berusia lanjut, tidak bekerja di luar pulau, suri rumah serta hanya menerima pendidikan asas pada zaman British sahaja. Justeru, mereka sesuai dijadikan sebagai responden bahasa Tidung. Hasil analisis data yang sangat asas itu, maka dapat dirumuskan bahawa bahasa Tidung mempunyai ikatan erat dengan bahasa-bahasa di bawah rumpun Murutik dan Dusunik. Namun, kajian lanjutan perlu dilakukan agar semua aspek linguistik bahasa ini dapat dipaparkan kepada khalayak penutur bahasa di Malaysia. -

Bugis and Makasar Two Short Grammars

Bugis and Makasar two short grammars edited and translated by Campbell Macknight South Sulawesi Studies 1 Bugis and Makasar two short grammars South Sulawesi Studies 1 Bugis and Makasar two short grammars edited and translated by Campbell Macknight Karuda Press Canberra 2012 © Charles Campbell Macknight This book is copyright. It may, however, be copied in whole or in part for research, criticism or review as permitted under the Copyright Act or for the purpose of private study. No re-sale of copies is permitted without the written permission of the publisher. First published 2012 South Sulawesi Studies Karuda Press PO Box 134, Jamison Centre ACT 2614, Australia This and other volumes in the series, South Sulawesi Studies, may be purchased from: Asia Bookroom Unit 2, 1–3 Lawry Place, Macquarie ACT 2614, Australia Telephone: (02) 6251 5191 Email: [email protected] Website: www.AsiaBookroom.com Volumes are also available for free download on the website: www.karuda.com.au National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry (pbk) Title: Bugis and Makasar : two short grammars / edited and translated by Campbell Macknight. ISBN: 9780977598328 (pbk.) Series: South Sulawesi studies ; 1 Subjects: Bugis language--Grammar. Makasar language--Grammar. Other Authors/Contributors: Macknight, Charles Campbell. Dewey Number: 499.2262 National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry (ebook) Title: Bugis and Makasar [electronic resource] : two short grammars / edited and translated by Campbell Macknight. ISBN: 9780977598335 (ebook : pdf) Printed by Vivid Print Services. Contents Foreword vii Makasar Introduction 3 Notes from Makasar lesson 9 Facsimile pages 21 Bugis Introduction 27 Note on the orthography of Bugis 31 !e Bugis language 33 Foreword THIS FIRST VOLUME in the series, South Sulawesi Studies, is devoted to English translations — from Dutch originals — of two short linguistic works on Bugis and Makasar, the major languages of the peninsula. -

JURNAL ILMU BUDAYA ISSN 2354 -7294 Volume 2, Nomor 1, Juni 2014

JURNAL ILMU BUDAYA ISSN 2354 -7294 Volume 2, Nomor 1, Juni 2014 Terbit dua kali setahun pada bulan Juni dan Desember. Berisi tulisan berupa hasil penelitian (lapangan atau kepustakaan), gagasan konseptual, kajian dan aplikasi teori mengenai kebudayaan. Ketua Dewan Redaksi Muhammad Hasyim Wakil Ketua Dewan Redaksi Hasbullah Penyunting Pelaksana Sumarwati Kramadibrata Poli Mardi Adi Armin Wahyuddin Fierenziana Getruida Junus Ade Yolanda Prasuri Kuswarini Andi Faisal Masdiana Pelaksana Tata Usaha Ester Rombe Shinta Ayu Pratiwi Alamat Penerbit/Redaksi : Jurusan Sastra Prancis Fakultas Ilmu Budaya - Universitas Hasanuddin Jl. Perintis Kemerdekaan km 10 Tamalanrea Makassar 90245. http://sastraprancis.unhas.ac.id email : [email protected] Jurnal Ilmu Budaya menerima sumbangan tulisan mengenai kebudayaan yang belum pernah diterbitkan dalam media lain. Naskah disusun berdasarkan format yang ada pada halaman belakang. (Petunjuk untuk penulis). Naskah yang masuk akan dievaluasi dan disunting oleh Dewan Redaksi tanpa mengubah isinya. JURNAL ILMU BUDAYA ISSN 2354-7294 Volume 2, Nomor 1, Juni 2014, hlm 161 - 342 DAFTAR ISI Proses Finalisasi Perbatasan Hindia-Belanda - North Borneo (Sabah): 161 – 169 Sebuah Catatan Atas Marjinalisasi Akhir Kesultanan Sulu Di Pesisir Timur-Laut Kalimantan Dave Lumenta, Dept. Antropologi, FISIP Universitas Indonesia Sabah Di Tengah Proses Dekolonisasi Di Asia Tenggara (1957-1968) 170 – 193 Dias Pradadimara Jurusan Ilmu Sejarah Universitas Hasanuddin Kewarganegaraan Dan Dilema Minoritas Pasca Kolonial Bercermin Kasus Sabah 194 – 210 Dan Kesultanan Sulu Ahmad Suaedy AW Centre-Universitas Indonesia Lembaga Pasca-Konflik Dan Proses Perdamaian Di Filipina Selatan 211 – 232 Lambang Trijono, Fisipol dan PSKP, UGM dan Peace and Development Initiative Indonesian Institute “Sabah” Dalam Perspektif Hukum Internasional: Milik Filipina Atau Malaysia? 233 – 251 Rina Shahriyani Shahrullah, Universitas Internasional Batam The Teaching Of Language 252 – 266 Suhartina. -

Consonant Geminates in Simalungun Language

Linguistik Indonesia, Agustus 2017, 145-158 Volume ke-35, No. 2 Copyright©2017, Masyarakat Linguistik Indonesia ISSN cetak 0215-4846; ISSN online 2580-24 CONSONANT GEMINATES IN SIMALUNGUN LANGUAGE Luh Anik Mayani* Badan Pengembangan dan Pembinaan Bahasa [email protected] Abstrak Penelitian ini bertujuan untuk mendeskripsikan proses morfofonemik yang dapat menghasilkan geminat dan jenis-jenis geminat dalam bahasa Simalungun. Jenis geminat dibedakan berdasarkan proses morfofonemiknya serta berdasarkan kesejatian geminat, yaitu tipe geminat sejati dan taksejati. Data dalam penelitian ini dikumpulkan melalui penelitian lapangan di Pematang Raya, Kecamatan Raya, Kabupaten Simalungun, Provinsi Sumatra Utara. Berdasarkan analisis dapat disimpulkan bahwa geminat dalam bahasa Simalungun selalu berada di tengah kata. Geminat yang ditemukan adalah [pp], [tt], [kk], [ss], [ll], [gg], [nn], dan [mm]. Berdasarkan proses morfofonemik, geminat dalam bahasa ini dapat dibagi menjadi empat, yaitu geminat yang merupakan hasil dari proses (1) asimilasi nasal mengikuti bunyi hambat homorganik yang ada di belakangnya, (2) velarisasi dan asimilasi, (3) asimilasi bunyi berbeda dalam konsonan rangkap, dan (4) geminat nasal. Berdasarkan kesejatian geminat, Simalungun memiliki geminat sejati dan taksejati. Geminat sejati bersifat leksikal; geminat taksejati dihasilkan melalui proses afiksasi dan klitisasi. Geminat sejati yang ditemukan adalah [pp], [tt], [ss], [kk], [gg] and [mm], sedangkan yang taksejati adalah [ss], [kk], [ll] and [nn]. Kata kunci: geminat konsonan, Simalungun, proses morfofonemik Abstract This study aims to describe morphophonemic processes which result in consonant geminates as well as to classify types of consonant geminates in Simalungun language. Types of geminates in this study are analyzed from the morphophonemic processes resulted in consonant geminates and from the true or fake types of geminates. -

Positional Neutralization: a Phonologization Approach to Typological Patterns

Positional Neutralization: A Phonologization Approach to Typological Patterns by Jonathan Allen Barnes B.A. (Columbia University) 1992 M.A. (University of California, Berkeley) 1995 M.A. (University of California, Berkeley) 1997 A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Linguistics in the GRADUATE DIVISION of the UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA, BERKELEY Committee in charge: Professor Sharon Inkelas, Chair Professor Andrew Garrett Professor Larry M. Hyman Professor Alan Timberlake Fall 2002 Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. Positional Neutralization: A Phonologization Approach to Typological Patterns ©2002 by Jonathan Allen Barnes Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. Abstract Positional Neutralization: A Phonologization Approach to Typological Patterns by Jonathan Allen Barnes Doctor of Philosophy in Linguistics University of California, Berkeley Professor Sharon Inkelas, Chair This study investigates the typology of patterns of positional neutralization, a term referring to systems in which, from a given set of oppositions, one structural position licenses a wider array of contrasts than another. Patterns of positional neutralization of vowel contrasts are surveyed in three pairs of strong and weak positions: stressed/unstressed, final/non-final, and initial/non-initial. For each pair, regularities involving the phonetic content of neutralization patterns are accounted for using a phonologization-based approach to typological patterns. In the phonologization model, phonetics influences phonology only by providing the gradient inputs out of which categorical patterns are created by phonologization. Perceptually ambiguous language-specific phonetic patterns are reinterpreted by listeners, producing new phonological representations of the relevant strings. -

Open Access College of Asia and the Pacific the Australian National University

Open Access College of Asia and the Pacific The Australian National University Papers from 12-ICAL, Volume 4 I WayanArka, Ni LuhNyoman Seri Malini, Ida Ayu Made Puspani (eds.) A-PL 019 / SAL 005 This volume contains papers describing and discussing language documentation and cultural practices in Austronesian languages. The issues discussed include language description, vitality and endangerment, community partnerships in language revitalisation and dictionary making, language maintenance of transmigrants, documenting and archiving verbal arts, traditional music and songs, cultural aspects in translation and politeness. This volume should be of interest to Austronesianists, sociolinguists and anthropologists. Asia-Pacific Linguistics SAL: Studies on Austronesian Languages EDITORIAL BOARD: I Wayan Arka, Mark Donohue, Bethwyn Evans, Nicholas Evans,Simon Greenhill, Gwendolyn Hyslop, David Nash, Bill Palmer, Andrew Pawley, Malcolm Ross, Paul Sidwell, Jane Simpson. Published by Asia-Pacific Linguistics College of Asia and the Pacific The Australian National University Canberra ACT 2600 Australia Copyright is vested with the author(s) First published: 2015 National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry: Title: Language documentation and cultural practices in the Austronesian world: papers from 12-ICAL, Volume 4 / edited by I Wayan Arka, Ni Luh Nyoman Seri Malini, Ida Ayu Made Puspani ISBN: 9781922185204 (ebook) Series: Asia-Pacific linguistics 019 / Studies on Austronesian languages 005 Subjects: Austronesian languages--Congresses. Dewey Number: 499.2 Other Creators/Contributors: Arka, I Wayan, editor. Seri Malini, Ni LuhNyoman, editor. Puspani, Ida Ayu Made, editor Australian National University. Department of Linguistics. Asia-Pacific Linguistics International Conference on Austronesian Linguistics (12th: 2012: Bali, Indonesia) Cover illustration: courtesy of Vida Mastrika, Typeset by I Wayan Arka and Vida Mastrika . -

Unnatural Phonology: a Synchrony- Diachrony Interface Approach

Unnatural Phonology: A Synchrony- Diachrony Interface Approach The Harvard community has made this article openly available. Please share how this access benefits you. Your story matters Citable link http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:40050094 Terms of Use This article was downloaded from Harvard University’s DASH repository, and is made available under the terms and conditions applicable to Other Posted Material, as set forth at http:// nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:dash.current.terms-of- use#LAA Unnatural Phonology: A Synchrony-Diachrony Interface Approach A dissertation presented by Gaˇsper Beguˇs to The Department of Linguistics in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the subject of Linguistics Harvard University Cambridge, Massachusetts May 2018 c 2018 Gaˇsper Beguˇs All rights reserved. Dissertation Advisor: Professor Kevin Ryan Author: Gaˇsper Beguˇs Unnatural Phonology: A Synchrony-Diachrony Interface Approach Abstract This dissertation addresses one of the most contested topics in phonology: which factors influence phonological typology and how to disambiguate these factors. I propose a new frame- work for modeling the influences of Analytic Bias and Channel Bias on phonological typology. The focus of the dissertation is unnatural alternations | those that operate in precisely the opposite direction from some universal and articulatorily- or perceptually-motivated phonetic tendency. Based on a typological survey of unnatural alternations and gradient phonotactic restrictions, I propose a diachronic device for explaining unnatural processes called the Blurring Process and argue that minimally three sound changes are required for an unnatural segmental process to arise (Minimal Sound Change Requirement; MSCR). -

The Effect of Buginese Language Transfer on Students’ English Pronunciation: a Case Study at SMAN 4 Barru

EEJ 9 (3) (2019) 334 - 341 English Education Journal http://journal.unnes.ac.id/sju/index.php/eej The Effect of Buginese Language Transfer on Students’ English Pronunciation: A Case Study at SMAN 4 Barru Lisa Binti Harun, Januarius Mujiyanto, Abdurrachman Faridi Universitas Negeri Semarang, Indonesia Article Info Abstract ________________ _________________________________________________________________ Article History: Indonesia is a country consists of various cultures and possesses hundreds of Recived 10 February native language. Therefore, in the process of l2 acquisition, the impact of L1 2019 on English articulation certainly is seen as a tough obstacle for the Accepted 04 July Indonesian EFL learners. In SLA, it is known as language transfer. Buginese 2019 Published 15 language as one of the native language existed in South Sulawesi also gave September 2019 positive and negative transfer towards English pronunciation. It was proven __________________ through a qualitative case study employed towards 20 students from XI IPA Keywords: 2 at SMAN 4 Barru. To obtain the data, several methods were undergone Language transfer, such as questionnaires, students’ recording, interview and observation. The Second language results of the study showed that Buginese language gave major negative acquisition, English transfer towards vowels /ə/ and /æ/, diphthongs /ɪə/, /eə/, /ʊə/ and /əʊ/, pronunciation consonants /p/, /f/, /ŋ/ and /n/, and also clusters skr/, /spl/ (initial), ____________________ /sk/, and /bl/. Moreover, this language gave minor negative transfer towards long vowels /i:/, /ɑ:/, /ɔ:/, and /u:/ and vowels /ɒ/, also consonants /ʤ/, /ʒ/, /z/, /v/, /ð/, /θ/, /ʧ/, and /ʃ/. It did not give any transfer towards diphthongs /eɪ/ (initial), /aɪ/ (initial and final) and /aʊ/.