The Hittites

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mortem Et Gloriam Army Lists Use the Army Lists to Create Your Own Customised Armies Using the Mortem Et Gloriam Army Builder

Army Lists Assyria and Babylon Contents Syro-Hittite 1100 to 901 BCE Phrygian 850 to 676 BCE Philistine 1100 to 732 BCE Early Iranian 836 to 550 BCE Dark Age Greek 1100 to 671 BCE Later Hebrew 800 to 586 BCE Hebrew 1000 to 801 BCE Cimmerian 750 to 630 BCE Phoenician 1000 to 332 BCE Urartian 746 to 585 BCE Early Arab 1000 to 301 BCE Neo-Assyrian Empire 745 to 681 BCE Mannaian 950 to 610 BCE Kushite Egyptian 732 to 656 BCE Libyan Egyptian 945 to 720 BCE Lydian 687 to 540 BCE Later Syro-Hittite 900 to 700 BCE Later Sargonid Assyrian v02 680 to 609 BCE Chaldean Babylonian 900 to 627 BCE Saitic Egyptian 664 to 525 BCE Later Vedic Indian 900 to 530 BCE Assyrian Babylonian v02 652 to 648 BCE Later Elamite 890 to 539 BCE Neo-Babylonian Empire 626 to 539 BCE Early Neo-Assyrian Empire 883 to 745 BCE Median Empire 620 to 550 BCE Early Urartian 860 to 747 BCE Version 2020.02: 1st January 2020 © Simon Hall Creating an army with the Mortem et Gloriam Army Lists Use the army lists to create your own customised armies using the Mortem et Gloriam Army Builder. There are few general rules to follow: 1. An army must have at least 2 generals and can have no more than 4. 2. You must take at least the minimum of any troops noted and may not go beyond the maximum of any. 3. No army may have more than two generals who are Talented or better. -

Nimrud. an Assyrian Imperial City Revealed. Oxbow Books, Oxford

9840_BIOR_2007/1-2_01 27-04-2007 09:05 Pagina 110 215 BIBLIOTHECA ORIENTALIS LXIV N° 1-2, januari-april 2007 216 Meuszynski und Paolo Fiorina, sowie die zahlreichen iraki- schen Kampagnen unter verschiedenen Ausgräbern geschil- dert. Im ersten Kapitel “The Land of Assyria — Setting the scene” wird sehr kurz die Geographie und die historische Entwicklung Assyriens bis ins 9. Jh. v. Chr. behandelt, bevor dann ausführlich die Periode der neuassyrischen Geschichte besprochen wird, in die Nimruds Glanzzeit fällt — also von AssurnaÒirpal II. bis zum Ende des assyrischen Reiches — und deren Hinterlassenschaften den Rahmen des Buches bil- den. Ein Überblick über die Anlage der Stadt und eine Besprechung der Stadtmauern, die in keinem der anderen Kapitel Platz fand, runden diesen Überblick ab. Das zweite Kapitel ist den Palästen auf der Akropolis gewidmet, wobei naturgemäß der Nord-West-Palast mit sei- ner Reliefausstattung2) den größten Raum einnimmt. Schon hier zeigt sich, daß es den Verfassern überzeugend gelingt, die Ergebnisse der verschiedenen Grabungen zu kombinie- ren und dennoch dabei die Verdienste der einzelnen Ausgrä- ber deutlich zu machen. Besonders ist zu würdigen, daß es den Verfassern gelang, die Ergebnisse der irakischen Gra- bungen seit 1988 im Bereich des Wohnflügels (bitanu) des Nord-West-Palastes zu berücksichtigen. Dies führt einerseits zu dem gegenüber den bisherigen Publikation (M.E.L. Mal- lowan, Nimrud and its Remains I, Tafel III) verbesserten Plan des Nord-West-Palastes durch Muzahim M. Hussein (S. 60, Abb. 33) und andererseits zu einer ausführlichen Darstellung der im Nord-West-Palast gefundenen Gräber assyrischer Königinnen aus dem 9. und 8. Jh. v. -

Assembling the Iron Age Levant: the Archaeology of Communities, Polities, and Imperial Peripheries

J Archaeol Res (2016) 24:373–420 DOI 10.1007/s10814-016-9093-8 Assembling the Iron Age Levant: The Archaeology of Communities, Polities, and Imperial Peripheries Benjamin W. Porter1 Published online: 5 March 2016 © Springer Science+Business Media New York 2016 Abstract Archaeological research on the Iron Age (1200–500 BC) Levant, a narrow strip of land bounded by the Mediterranean Sea and the Arabian Desert, has been balkanized into smaller culture historical zones structured by modern national borders and disciplinary schools. One consequence of this division has been an inability to articulate broader research themes that span the wider region. This article reviews scholarly debates over the past two decades and identifies shared research interests in issues such as ethnogenesis, the development of territorial polities, economic intensification, and divergent responses to imperial interventions. The broader contributions that Iron Age Levantine archaeology offers global archaeological inquiry become apparent when the evidence from different corners of the region is assembled. Keywords Empire · Ethnicity · Middle East · State Introduction The Levantine Iron Age (c. 1200–500 BC) was a transformative historical period that began with the decline of Bronze Age societies throughout the Eastern Mediterranean and concluded with the collapse of Babylonian imperial rule at the end of the sixth century BC. Sandwiched between Mesopotamia and the Mediterranean Sea on the east and west, and Anatolia and Egypt on the north and south (Figs. 1 and 2), respectively, a patchwork of Levantine societies gradually established political polities, only to see them dismantled and reshaped in the wake & Benjamin W. Porter [email protected] 1 Phoebe A. -

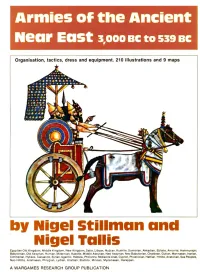

Armies of the Ancient Near E

Armies of the Ancient Near East 3,000 BC to 539 BC Organisation, tactics, dress and equipment. 210 illustrations and 9 maps. by Nigel StiUman and Nigel Tallis Egyptian Old Kingdom, Middle Kingdom, New Kingdom, S,itc, libyan, Nubian, KU 5hiu~. Sumerian, Akkadian, Eblaitc. Amoritc, HammUl1lpic lhhylonian, Old Assyrian, Human, MilaMian, K.ssitc, Middle: Assyrian, Neo Assyrian, Neo Babylonia n, Chaldun, GUlian, Mannatan, Iranian, Cimmerian, Hyluos. Canaanite, Syrian, Ugaritic, Hebrew, Philistine, Midianitc Arab, Cypriot, Phoenician, Hanian. Hillile, Anatolian, Sea Peoples, Neo Hinile, Aramaun, Phrygian. Lydian. Uranian, Elamilc, Minoan. Mycenaean, Harappan. A WARGAMES RESEARCH GROUP PUBLICATION INTRODUCTION This book. chronologically the finl in the W.R.G. series, attempts the diflkulltaP: ofducribingl he military organisa tion and equipment of the many civilisations ohhe ancienl Near East over a period of 2,500 years. It is du.slening to note tbatthis span oftime is equivalent to half of all recorded history and that a single companion volume, should anyone wish to attempt it, wou.ld have to encompass the period 539 BC to 1922 AD! We hope that our researches will rcOca the: .... St amount of archacologiaJ, pictorial and tarual evidence ..... hich has survived and been rW)vered from this region. It is a matter of some rcp-ct that tbe results of much of the research accumulated in this century has tended to be disperKd among a variety of sometimes obscure publications. Consequently, it is seldom that this mJterial is aplo!ted to its full potcoti.al IS a source for military history. We have attempted 10 be as comptcbensive IS possible and to make UK of the lcuer known sourcCI and the most recent ruearm. -

Ancient Records of Egypt, Volume

class93% BO~~BVR Library of ~delbertCollege V.3 of Western Rerane Unlvsrsity, Olsvoiand. 0. ANCIENT RECORDS OF EGYPT ANCIENT RECORDS UNDER THE GENERAL EDITORSHIP OF WILLIAM RAINEY HARPER ANCIENT RECORDS OF ASSYRIA AND BABYLONIA EDITED BY ROBERT FRANCIS HARPER ANCIENT RECORDS OF EGYPT EDITED BY JAMES HENRY. BREARTED ANCIENT RECORDS OF PALESTINE, PH(EN1CIA AND SYRIA EDITED BY WILLIAM RAINEX HARPEB ANCIENT RECORDS OF EGYPT HISTORICAL DOCUMENTS FROM THE EARLIEST TIMES TO THE PERSIAN CONQUEST. COLLECTED EDITED AND TRANSLATED WITH COMMENTARY JAMES HENRY BREASTED, PH.D. PROFESSOR OF EGYPTOLOGY AND ORIENTAL HISTORY IN TIIE UNIVBEWTY OF CHICAGO VOLUME I11 WHE NINETEENTH DYNASTY CHICAGO THE UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO PRESS 1906 LONDON: LUZAC & CO. LEIPZIGI : OTTO HABRASSOWITZ Published May 1906 QLC.%, Composed and Printed By The University of Chicago Press Chicago. Illinois. U. S. A. TABLE OF CONTENTS VOLUME I THEDOCUMENTARY SOURCES OF EGYPTIANHISTORY . CHRONOLOGY........... CHRONOLOGICALTABLE ........ THEPALERMO STONE: THE FIRST TO THE FIFTH DYNASTIES I. Predynastic Kings ........ I1. First Dynasty ......... 111. Second Dynasty ........ IV. Third Dynasty ......... V . Fourth Dynasty ........ VI . Fifth Dynasty ......... THETHIRD DYNASTY ........ Reign of Snefru ...s . b ;- .... Sinai Inscriptions ......... Biography of Methen ........ THE FOURTHDYNASTY ........ Reign of Khufu ......... Sinai Inscriptions ......... Inventory Stela ......... Examples of Dedication Inscriptions by Sons . Reign of Khafre ......... Stela of Mertitydtes ........ Will of Prince Nekure. Son of King Khafre ... Testamentary Enactment of an Unknown Official. Establishing the Endowment of His Tomb by the Pyramid of Khafre ........ Reign of Menkure ......... Debhen's Inscription. Recounting King Menkure's Erec- tion of a Tomb for Him ....... TEE RFTHDYNASTY ......... Reign of Userkaf ......... v vi TABLE OF CONTENTS Testamentary Enactment of Nekonekh .... I. -

Kimmer'lerin Anadolu'ya Girisleri Ve M. Ö. 7 Nciyozyilda Asur Devletinin Anadolu Ile Münasebetleri

KİMMER'LERİN ANADOLU'YA GİRİSLERİ VE M. Ö. 7 NCİYOZYILDA ASUR DEVLETININ ANADOLU İLE MÜNASEBETLERİ Dr. KADRİYE TANSUĞ Sumeroloji Asistan ı Asur tarihinde Sargonid'ler devri denen M. ö. 722 - 626 y ılları arasındaki zamanda kudretli Asur k ırallarını daimi surette me şgul eden hâdiselerden birisi de Kimmer'lerin Anadolu'ya giri şleri olmuştur. Bu münasebetle, bat ı, orta ve güney do ğu Anadolu zaman zaman askeri ve siyasi hareketlere sahne olmu ş bulunduğundan zikredilen tarih fasl ı, memleketimizin eski ça ğlarının önemli bir safhasıdır. Kimmer'ler hakkı ndaki bilgilerimiz henüz çok noksand ır °. Aşağıdaki denemede, son y ıllarda yayınlanmış olan ve Asurbanipal (668 - 626) zaman ındaki Anadolu — Asur münasebetlerini daha iyi anla- mamıza yard ım eden, Ninive metni (Bk. s. 538 alt not 12) denen bir vesika işlenmek ve ilgili di ğer kaynaklar yeniden k ıymetlendirilmek suretiyle devrin tarihi ayd ınlatılmağa çal ışılmıştır. Ancak daha evvel bu bölgenin tarihi manzaras ına ve Asurpanipal zaman ı na gelinceye kadarki Kimmer — Asur münasebetlerine bir göz atal ım. Kimmer'lerin Anadolu'ya gir- meğe başladıkları tarihte Anadolu'nun siyasi manzaras ı şöyle idi : Asur devleti, Sargon (721 - 705) zaman ında çok kuvvetlenmi ş olup Fırat' ın doğusundaki güney Anadolu bölgelerinden ba şka, bu hatt ın batısındaki Kargam ış, Zincirli (Sam'al), Mara ş (Gurgum) , Malatya (Milid) , Adana, Tarsus (Que) ve Kayseri m ıntakaları nı da ele geçir- mişti. Halefi Sanherib (704 - 682) ça ğı nda Tabal 2, Hilakku ve Kam- Kimmerler hakk ı nda yay ı mlanm ış olan ba şl ı ca yaz ı lar Streck, Asurbanipal I, s. CCCXXI (916). -

Assembling the Iron Age Levant: the Archaeology of Communities, Polities, and Imperial Peripheries

UC Berkeley Postprints Title Assembling the Iron Age Levant: The Archaeology of Communities, Polities, and Imperial Peripheries Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/9tj5d97n Journal Journal of Archaeological Research, 24(4) ISSN 1059-0161 1573-7756 Author Porter, Benjamin W Publication Date 2016-03-05 DOI 10.1007/s10814-016-9093-8 Peer reviewed eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California J Archaeol Res (2016) 24:373–420 DOI 10.1007/s10814-016-9093-8 Assembling the Iron Age Levant: The Archaeology of Communities, Polities, and Imperial Peripheries Benjamin W. Porter1 Published online: 5 March 2016 © Springer Science+Business Media New York 2016 Abstract Archaeological research on the Iron Age (1200–500 BC) Levant, a narrow strip of land bounded by the Mediterranean Sea and the Arabian Desert, has been balkanized into smaller culture historical zones structured by modern national borders and disciplinary schools. One consequence of this division has been an inability to articulate broader research themes that span the wider region. This article reviews scholarly debates over the past two decades and identifies shared research interests in issues such as ethnogenesis, the development of territorial polities, economic intensification, and divergent responses to imperial interventions. The broader contributions that Iron Age Levantine archaeology offers global archaeological inquiry become apparent when the evidence from different corners of the region is assembled. Keywords Empire · Ethnicity · Middle East · State Introduction The Levantine Iron Age (c. 1200–500 BC) was a transformative historical period that began with the decline of Bronze Age societies throughout the Eastern Mediterranean and concluded with the collapse of Babylonian imperial rule at the end of the sixth century BC. -

History of the World Research

History of the World Research History of Civilisation Research Notes 200000 - 5500 BCE 5499 - 1000 BCE 999 - 500 BCE 499 - 1 BCE 1 CE - 500 CE 501 CE - 750 CE 751 CE - 1000 1001 - 1250 1251 - 1500 1501 - 1600 1601 - 1700 1701 - 1800 1801 - 1900 1901 - Present References Notes -Prakrit -> Sanskrit (1500-1350 BCE) -6th Dynasty of Egypt -Correct location of Jomon Japan -Correct Japan and New Zealand -Correct location of Donghu -Remove “Armenian” label -Add D’mt -Remove “Canaanite” label -Change Gojoseon -Etruscan conquest of Corsica -322: Southern Greece to Macedonia -Remove “Gujarati” label (to 640) -Genoa to Lombards 651 (not 750) Add “Georgian” label from 1008-1021 -Rasulids should appear in 1228 (not 1245) -Provence to France 1481 (not 1513) -Yedisan to Ottomans in 1527 (not 1580) -Cyprus to Ottoman Empire in 1571 (not 1627) -Inner Norway to sweden in 1648 (not 1721) -N. Russia annexed 1716, Peninsula annexed in 1732, E. Russia annexed 1750 (not 1753) -Scania to Sweden in 1658 (not 1759) -Newfoundland appears in 1841 (not 1870) -Sierra Leone -Kenya -Sao Tome and Principe gain independence in 1975 (not 2016) -Correct Red Turban Rebellion --------- Ab = Abhiras Aby = Abyssinia Agh = Aghlabids Al = Caucasian Albania Ala = Alemania Andh = Andhrabhrtya Arz = Arzawa Arm = Armenia Ash = Ashanti Ask = Assaka Assy/As = Assyria At = Atropatene Aus = Austria Av = Avanti Ayu = Ayutthaya Az = Azerbaijan Bab = Babylon Bami = Bamiyan BCA = British Central Africa Protectorate Bn = Bana BNW = Barotseland Northwest Rhodesia Bo = Bohemia BP = Bechuanaland -

Part 1. the Table of Nations

EN Tech. J., vol. 4, 1990, pp. 67–92 The Early History of Man: Part 1. The Table of Nations BILL COOPER INTRODUCTION creationist scholars who have specialised in their study. Likewise, the descent of, say, the American Indians or the The following is the first of a two-part study regard Chinese or other Mongoloid races is not dealt with, simply ing the early post-Flood history of mankind. In Part 1, we because they lie outside the scope of the present work. shall examine what documentary evidence exists that Rather, Part 1 in particular is concerned only with that verifies both the presence and activities of those charac documentary evidence from those early post-Flood na ters and peoples of whom explicit mention is made in that tions of the Middle East who had direct contact with one portion of Genesis that is known as the Table of Nations. another, and who preserved in written records those We shall find in this part of the study that the documentary names that are explicitly mentioned in the Genesis record. evidence available to us is at an astonishing variance with The notices that accompany each genealogy are thus very the claims that are currently being put forward by the brief collections of recorded historical facts and subse modernist school of historical and biblical interpretation. quent information that pertain to the names under which According to this school of thought, the Genesis record is they appear, and which have been gleaned over many without historical foundation; whereas we shall see in this years from a wide variety of sources. -

Sargon II, King of Assyria

SARGON II, KING OF ASSYRIA Press SBL A RCHAEOLOGY AND BIBLICAL STUDIES B rian B. Schmidt, General Editor Editorial Board: Aaron Brody Annie Caubet Billie Jean Collins Israel Finkelstein André Lemaire Amihai Mazar Herbert Niehr Christoph Uehlinger Number 22 Press SBL SARGON II, KING OF ASSYRIA Josette Elayi Press SBL Atlanta C opyright © 2017 by Josette Elayi A ll rights reserved. No part of this work may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying and recording, or by means of any information storage or retrieval system, except as may be expressly permit- ted by the 1976 Copyright Act or in writing from the publisher. Requests for permission should be addressed in writing to the Rights and Permissions Office,B S L Press, 825 Hous- ton Mill Road, Atlanta, GA 30329 USA. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Names: Elayi, Josette, author. Title: Sargon II, King of Assyria / by Josette Elayi. Description: Atlanta : SBL Press, 2017. | Series: Archaeology and biblical studies ; number 22 | Includes bibliographical references and index. Identifiers: LCCN 2017009197 (print) | LCCN 2017012087 (ebook) | ISBN 9780884142232 (ebook) | ISBN 9780884142249 (hardcover : alk. paper) | ISBN 9781628371772 (pbk. : alk. paper) Subjects: LCSH: Sargon II, King of Assyria, –705 B.C. | Assyria—History. | Assyria—His- tory, Military. Classification: LCC DS73.8 (ebook) | LCC DS73.8 .E43 2017 (print) | DDC 935/.03092 [B] —dc23 LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2017009197 Press Printed on acid-free paper. SBL C ontents A uthor’s Note ...................................................................................................vii Abbreviations ....................................................................................................ix Introduction .......................................................................................................1 1. Portrait of Sargon .....................................................................................11 2. -

Chapter 21 Kizzuwatna and the Euphrates States: Kummaha, Elbistan, Malatya Philology J. David Hawkins and Mark Weeden SOAS

Chapter 21 Kizzuwatna and the Euphrates States: Kummaha, Elbistan, Malatya Philology J. David Hawkins and Mark Weeden SOAS, University of London 1. Introduction Kizzuwatna is defined in a Middle Hittite letter from Maşathöyük as a “primary watchpost”, a border region, which the writer of the letter explains is just as exposed as Zikkasta in the area of Maşat itself.1 Kizzuwatna itself had only been annexed to the Hittite power-sphere since the reign of Tudhaliya I in the mid 15th century BC as outlined in the treaty with Sunassura.2 Prior to this it had been subject to Hurrian overlordship, with a basically Syrian geo-political orientation.3 Hittite access to Syria is one of the key themes associated with the area of Kizzuwatna. One traditional assumption has been that this passed through the Cilician Gates into Plain Cilicia and then over one of the Amanus passes into Syria. Cogent objections have been made to this view, especially when it involves the passage of armies through difficult terrain involving precarious passes.4 Where exactly its borders lay and where its main cities are to be located have remained problematic issues, although considerable advances have been made in the last 15 years. The identity of the city/land of Kummanni and the city/land of Kizzuwatna was observed early on, as they alternate as readings in duplicate manuscripts of the same texts as well as in the titles of identical people or gods.5 This, along with an alleged textual association of Kizzuwatna with iron on the one hand and the coast on the other, led to an early identification of Kizzuwatna with Comana Pontica on the Black Sea coast. -

Achaemenid and Greco- Macedonian Inheritances in the Semi-Hellenised Kingdoms

ACHAEMENID AND GRECO- MACEDONIAN INHERITANCES IN THE SEMI-HELLENISED KINGDOMS OF EASTERN ASIA MINOR Submitted by Cristian Emilian Ghiţă to the University of Exeter as a thesis for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Classics, January 2010. This thesis is available for Library use on the understanding that it is copyright material and that no quotation from the thesis may be published without proper acknowledgement. I certify that all material in this thesis which is not my own work has been identified and that no material has previously been submitted and approved for the award of a degree by this or any other University. ......................................................................................... ABSTRACT he present thesis aims to analyse the manner in which the ethnically and Tculturally diverse environment of Eastern Anatolia during the Hellenistic era has influenced the royal houses of the Mithradatids, Ariarathids, Ariobarzanids and Commagenian Orontids. The focus of analysis will be represented by the contact and osmosis between two of the major cultural influences present in the area, namely the Iranian (more often than not Achaemenid Persian) and Greco-Macedonian, and the way in which they were engaged by the ruling houses, in their attempt to establish, preserve and legitimise their rule. This will be followed in a number of fields: dynastic policies and legitimacy conceptions, religion, army and administration. In each of these fields, discrete elements betraying the direct influence of one or the other cultural traditions will be followed and examined, both in isolation and in interaction with other elements, together with which they form a diverse, but nevertheless coherent whole.