2014.Pdf (3.932Mb)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The IRGC in the Age of Ebrahim Raisi: Decision-Making and Factionalism in Iran’S Revolutionary Guard

The IRGC in the Age of Ebrahim Raisi: Decision-Making and Factionalism in Iran’s Revolutionary Guard SAEID GOLKAR AUGUST 2021 KASRA AARABI Contents Executive Summary 4 The Raisi Administration, the IRGC and the Creation of a New Islamic Government 6 The IRGC as the Foundation of Raisi’s Islamic Government The Clergy and the Guard: An Inseparable Bond 16 No Coup in Sight Upholding Clerical Superiority and Preserving Religious Legitimacy The Importance of Understanding the Guard 21 Shortcomings of Existing Approaches to the IRGC A New Model for Understanding the IRGC’s Intra-elite Factionalism 25 The Economic Vertex The Political Vertex The Security-Intelligence Vertex Charting IRGC Commanders’ Positions on the New Model Shades of Islamism: The Ideological Spectrum in the IRGC Conclusion 32 About the Authors 33 Saeid Golkar Kasra Aarabi Endnotes 34 4 The IRGC in the Age of Ebrahim Raisi Executive Summary “The Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps [IRGC] has excelled in every field it has entered both internationally and domestically, including security, defence, service provision and construction,” declared Ayatollah Ebrahim Raisi, then chief justice of Iran, in a speech to IRGC commanders on 17 March 2021.1 Four months on, Raisi, who assumes Iran’s presidency on 5 August after the country’s June 2021 election, has set his eyes on further empowering the IRGC with key ministerial and bureaucratic positions likely to be awarded to guardsmen under his new government. There is a clear reason for this ambition. Expanding the power of the IRGC serves the interests of both Raisi and his 82-year-old mentor, Ayatollah Ali Khamenei, the supreme leader of the Islamic Republic. -

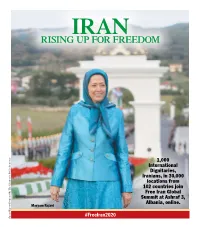

Rising up for Freedom

IRAN RISING UP FOR FREEDOM 1,000 International Dignitaries, Iranians, in 30,000 locations from 102 countries join Free Iran Global Summit at Ashraf 3, Albania, online. Maryam Rajavi #FreeIran2020 Special Report Sponsored The by Alliance Public for Awareness Iranian dissidents rally for regime change in Tehran BY BEN WOLFGANG oppressive government that has ruled Iran from both political parties participating has proven it can’t deliver for its people. tHe WasHInGtOn tImes since the Islamic Revolution of 1979. Leaders represented a who’s who list of American “The Iranian people want change, to of the NCRI, which is comprised of multiple “formers,” including former Sen. Joseph I. have democracy, finally to have human Iran’s theocracy is at the weakest point other organizations, say the council has seen Lieberman of Connecticut, former Penn- rights, to finally have economic wealth, of its four-decade history and facing un- its stature grow to the point that Iranian sylvania Gov. Tom Ridge, former Attorney no more hunger. The will of the people precedented challenges from a courageous officials can no longer deny its influence. General Michael Mukasey, retired Marine is much stronger than any oppressive citizenry hungry for freedom, Iranian dis- The NCRI has many American support- Commandant James T. Conway and others. measure of an Iranian regime,” said Martin sidents and prominent U.S. and European ers, including some with close relationships Several current U.S. officials also delivered Patzelt, a member of German Parliament. politicians said Friday at a major interna- to Mr. Trump, such as former New York remarks, including Sen. -

National Subway Train Developed Despite Sanctions

WWW.TEHRANTIMES.COM I N T E R N A T I O N A L D A I L Y 8 Pages Price 50,000 Rials 1.00 EURO 4.00 AED 42nd year No.13904 Sunday MARCH 14, 2021 Esfand 24, 1399 Rajab 30, 1442 Persons with military Skocic protests AFC over Free medical services “The Sand Wolf” background can stand choosing Bahrain as for people aged hunts Iran’s Flying as candidates Page 2 Group C host Page 3 over 65 Page 7 Turtle Page 8 Iranian heavy crude oil price rises 11.5% in February: OPEC TEHRAN- Iranian heavy oil price increased in the previous year’s same period. $6.28 in February to register an 11.5-per- The report put Iranian crude output for Illogical presence cent rise compared to the previous month, February at 2.12 million barrels per day according to OPEC’s latest monthly report. indicating a 35,000-bpd increase compared See page 3 Iran sold its heavy crude oil at $60.66 to the figure for the previous month. U.S. faces trouble justifying presence in Iraq per barrel in the mentioned month, com- Based on OPEC data, the country’s av- pared to January’s $54.38 per barrel, IRIB erage crude output in the fourth quarter reported. of 2020 stood at 1.993 million barrels According to the report, the country’s per day indicating a near 45,000-bpd average heavy crude price was $57.52 from rise compared to the figure for the third the beginning of 2021 up to the report’s quarter of the year. -

Report Worldwide Cultural Differences

Worldwide cultural differences in socio-ethical views in relation to biotechnology A report commissioned by the COGEM (Netherlands Commission on Genetic Modification) Dr. Henk van den Belt Prof. Dr. Jozef Keulartz April, 2007 This report was commissioned by COGEM. The contents of this publication are the sole responsibility of the authors. The contents of this publication may in no way be taken to represent the views of COGEM. Dit rapport is in opdracht van de Commissie Genetische Modificatie (COGEM) samengesteld. De meningen die in het rapport worden weergegeven zijn die van de auteurs en weerspiegelen niet noodzakelijkerwijs de mening van de COGEM. 2 Contents Voorwoord/Preface …………………5 Chapter 1 Worldwide cultural differences in socio-ethical views in relation to biotechnology: Overview and summary ……………………..7 Chapter 2 Monsters, boundary work and framing: Biotechnology from an anthropological perspective …………………….27 Chapter 3 Hwang Woo Suk and the Korean stem cell debacle: Scientific fraud, techno-nationalism and the ‘Wild East’ ……………………..47 Chapter 4 East Asia and the “GM Cold War”: The international struggle over precaution, labelling and segregation ………….77 3 4 Voorwoord/Preface Het voorliggende rapport Worldwide Cultural Differences in Socio-Ethical Views in Relation to Biotechnology (Mondiale cultuurverschillen in de ethisch maatschappelijke opvattingen i.v.m. biotechnologie) is samengesteld in opdracht van de Commissie Genetische Modificatie (COGEM). Het is mede bedoeld ter voorbereiding van de nieuwe Trendanalyse Biotechnologie die in 2007 zal worden uitgebracht. De onderzoekswerkzaamheden (voornamelijk ‘desk research’) zijn verricht door dr. Henk van den Belt onder directe supervisie van Prof. dr. Jozef Keulartz. De uitvoering van het project is begeleid door een begeleidingscommissie waarin Prof. -

13881 Saturday FEBRUARY 13, 2021 Bahman 25, 1399 Rajab 1, 1442

WWW.TEHRANTIMES.COM I N T E R N A T I O N A L D A I L Y 8 Pages Price 50,000 Rials 1.00 EURO 4.00 AED 42nd year No.13881 Saturday FEBRUARY 13, 2021 Bahman 25, 1399 Rajab 1, 1442 Ghalibaf: Iran’s strategic Ali Moradi Iran sits at UN TIR Even ‘illegal migrants’ principle is to develop nominated for executive board for 3rd in Iran will get ties with China Page 2 IWF presidency Page 3 consecutive time Page 4 COVID-19 vaccine Page 7 Iran’s top judge holds talks with Iraqi leaders SPECIAL ISSUE TEHRAN - Iran’s Judiciary Chief Ebra- him Raeisi held talks with several Iraqi political and judicial leaders including President Barham Salih, Prime Min- ister Mustafa al-Kadhimi, and Head of Iraq’s Supreme Judicial Council Faiq Zaidan. The man of On Monday, February 8, Ayatollah Raisi paid a two-day visit to Iraq. During his meeting with his Iraqi counterpart, the two sides signed three memoranda of understanding to boost judicial and legal cooperation between the two neighboring countries. theoretical Continued on page 3 Bandar Abbas-Latakia direct shipping line to be launched by early Mar. battlefields TEHRAN - Iran is going to establish a direct shipping line between its south- ern port of Bandar Abbas and Syria’s Mediterranean port of Latakia on March In memory of Ayatollah 10, Head of Iran-Syria Joint Chamber of Commerce Keyvan Kashefi announced. Mohammad Taghi Continued on page 4 Mesbah Yazdi, the Iranian “Yadoo” tops at 39th renowned theorist and Fajr Film Fsetival philosopher TEHRAN – War drama “Yadoo” was the top winner of the 39th Fajr Film Festival by garnering awards in several categories, including best film and best director. -

Iran: a Revolutionary Republic in Transition

Iran: a revolutionary republic in transition in republic a revolutionary Iran: This Chaillot Paper examines recent domestic developments in the Islamic Republic of Iran. The volume presents an in-depth assessment of the far- reaching changes that the Iranian state and Iranian society have undergone since the 1979 revolution, with a particular focus on the social and political turmoil of the past five years. IRAN: It is clear that in many ways the Islamic Republic is in the throes of a transition A REVOLUTIONARY REPUBLIC where many of its fundamental tenets are being called into question. Profound and ongoing internal transformations in Iranian society already affect the country’s foreign policy posture, as some of its domestic and external issues IN TRANSITION converge and will most likely continue to do so. Pertinent examples are the nuclear issue and the socio-political upheaval in neighbouring Arab countries. Edited by Rouzbeh Parsi Edited by Rouzbeh Parsi, the volume features contributions from five authors who are all specialists in various aspects of Iranian politics and society. Each Edited by Rouzbeh Parsi by RouzbehEdited Parsi Chaillot Papers | February 2012 author explores some of the most crucial variables of the Iranian body politic. Their focus on distinct dimensions of Iranian society and culture casts light on the changes afoot in contemporary Iran and how the political elite controlling the state respond to these challenges. ISBN 978-92-9198-198-4 published by phone: + 33 (0) 1 56 89 19 30 ISSN 1017-7566 the European Union fax: + 33 (0) 1 56 89 19 31 QN-AA-12-128-EN-C Institute for Security Studies e-mail: [email protected] doi:10.2815/27423 100, avenue de Suffren www.iss.europa.eu PAPER CHAILLOT 75015 Paris - France 128 128 CHAILLOT PAPERS BOOKS In January 2002 the Institute for Security Studies (EUISS) became an 127 120 2010 QUELLE DÉFENSE EUROPÉENNE autonomous Paris-based agency of the European Union. -

Reform Versus Radicalism in the Islamic Republic

Reform Versus Radicalism in the Islamic Republic By David Menashri he 1979 islamic revolution marked a major turning point in modern Iran’s history that has had far-reaching consequences both within the country and beyond. The aim of the revolution was not sim- ply to replace the Shah’s monarchical government with a new, repub- lican system, but to radically restructure the Iranian state and society Tthrough the implementation of a new Islamic doctrine. To many Iranians, as well as scores of others throughout the Middle East and elsewhere, the Islamic revolution embodied a promise—and an expectation—of a brighter future with greater pros- perity and more liberty. In the three decades since the revolution, the Islamic Republic of Iran has demon- strated an impressive measure of political resilience and continuity. However, the popular hopes and expectations of the revolutionary era have remained, thus far, largely unsatisfied. Nowadays, the Iranian regime is struggling to find viable ways to cope with a seemingly ever-expanding array of governance challenges—from in- tensifying power struggles between competing factions within the country’s ruling elites to crippling social and economic malaise, a hostile regional security environment, and rising popular discontent at home. Needless to say, many of these challenges are products of the Islamic regime’s own making. In response to these challenges, Iranian politics in the contemporary era have tended to swing between two poles—reform and radicalism. These are best illustrated by the distinctive visions of the Iranian polity’s two main camps, which are perhaps best expressed by their most visible leaders—namely, President Mahmoud Ahmadinejad, 56 ■ CURRENT TRENDS IN ISLAMIST IDEOLOGY / VOL. -

Commercial Risks

Barak Seener Barak Commercial Risks | The Trump Administration’s withdrawal on May 8, 2018, from the uncertainty accompanying the fate of Market the Iranian Entering Risks Commercial Entering the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA) will cost the Iranian economy a heavy price. It has the Iranian Market created wariness on the part of foreign investors, especially European investors, and prevented the Iranian market from significantly reaping the fruits of the deal. Prior to the withdrawal from the JCPOA, there were numerous preparations by foreign businesses and investors to enter the Iranian market, but only a marginal number of deals and investments materialized. Following the American withdrawal, major European companies began to move their business away from Iran and cut their trade with it. Even though the European Union is determined to stick to the deal, it will be very difficult for the EU to convince companies to prefer the Iranian market over the American market, once secondary sanctions are resumed. Russian and Chinese companies may try to fill the gap but may encounter difficulties. Why Sanctions Make Investment Although India has declared that it will abide only in the Islamic Republic of Iran by UN sanctions, it appears that Indian companies will hesitate to ignore the American threat. a High‑Risk Proposition Barak Seener Jerusalem Center for Public Affairs Commercial Risks Entering the Iranian Market Why sanctions make investment in the Islamic Republic of Iran a high-risk proposition Barak Seener Jerusalem Center for Public Affairs Read this publication online: http://jcpa.org/commercial-risks-entering-the-iranian-market/ © 2018 Jerusalem Center for Public Affairs 13 Tel Hai St., Jerusalem, 9210717 Israel Email: [email protected] Tel: 972-2-561-9281 | Fax: 972-2-561-9112 Jerusalem Center Websites: www.jcpa.org (English) | www.jcpa.org.il (Hebrew) www.jcpa-lecape.org (French) | www.jer-zentrum.org (German) www.dailyalert.org The Jerusalem Center for Public Affairs is a non-partisan, not-for-profit organization. -

Understanding Iran

THE ARTS This PDF document was made available CHILD POLICY from www.rand.org as a public service of CIVIL JUSTICE the RAND Corporation. EDUCATION ENERGY AND ENVIRONMENT Jump down to document6 HEALTH AND HEALTH CARE INTERNATIONAL AFFAIRS The RAND Corporation is a nonprofit NATIONAL SECURITY research organization providing POPULATION AND AGING PUBLIC SAFETY objective analysis and effective SCIENCE AND TECHNOLOGY solutions that address the challenges SUBSTANCE ABUSE facing the public and private sectors TERRORISM AND HOMELAND SECURITY around the world. TRANSPORTATION AND INFRASTRUCTURE Support RAND WORKFORCE AND WORKPLACE Purchase this document Browse Books & Publications Make a charitable contribution For More Information Visit RAND at www.rand.org Explore the RAND National Security Research Division View document details Limited Electronic Distribution Rights This document and trademark(s) contained herein are protected by law as indicated in a notice appearing later in this work. This electronic representation of RAND intellectual property is provided for non-commercial use only. Unauthorized posting of RAND PDFs to a non-RAND Web site is prohibited. RAND PDFs are protected under copyright law. Permission is required from RAND to reproduce, or reuse in another form, any of our research documents for commercial use. For information on reprint and linking permissions, please see RAND Permissions. This product is part of the RAND Corporation monograph series. RAND monographs present major research findings that address the challenges facing the public and private sectors. All RAND mono- graphs undergo rigorous peer review to ensure high standards for research quality and objectivity. Understanding Iran Jerrold D. Green, Frederic Wehrey, Charles Wolf, Jr. -

Iran's Censorship of Wikipedia

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons Center for Global Communication Studies Iran Media Program (CGCS) 11-2013 Citation Filtered: Iran’s Censorship of Wikipedia Nima Nazeri Collin Anderson Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/iranmediaprogram Part of the Communication Technology and New Media Commons, and the Near and Middle Eastern Studies Commons Recommended Citation Nazeri, Nima and Anderson, Collin. (2013). Citation Filtered: Iran’s Censorship of Wikipedia. Iran Media Program. Retrieved from https://repository.upenn.edu/iranmediaprogram/10 This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/iranmediaprogram/10 For more information, please contact [email protected]. Citation Filtered: Iran’s Censorship of Wikipedia Abstract Using proxy servers in Iran, researchers Collin Anderson and Nima Nazeri identified every blocked Persian language Wikipedia article and divided blocked pages into ten categories to determine the type of content state censors are most adverse. In total, 963 blocked articles were found, covering a range of socio- political and sexual content including politics, journalism, the arts, religion, sex, sexuality, and human rights. Censors repeatedly targeted Wikipedia pages about government rivals, minority religious beliefs, and criticisms of the state, officials, and the police. Just under half of the blocked Wiki-pages are biographies, including pages about individuals the authorities have allegedly detained or killed. Based on prior research, it is known that Iran’s Internet filtration relies on blacklists of specifically designated URLs and URL keywords. Keyword filtration blindly blocks pages that contain prohibited character patterns in the URL. Sexual content is the main target of keywords, for example most keywords are sexual and/or profane terms. -

Iran: a Revolutionary Republic in Transition

Iran: a revolutionary republic in transition in republic a revolutionary Iran: This Chaillot Paper examines recent domestic developments in the Islamic Republic of Iran. The volume presents an in-depth assessment of the far- reaching changes that the Iranian state and Iranian society have undergone since the 1979 revolution, with a particular focus on the social and political turmoil of the past five years. IRAN: It is clear that in many ways the Islamic Republic is in the throes of a transition A REVOLUTIONARY REPUBLIC where many of its fundamental tenets are being called into question. Profound and ongoing internal transformations in Iranian society already affect the country’s foreign policy posture, as some of its domestic and external issues IN TRANSITION converge and will most likely continue to do so. Pertinent examples are the nuclear issue and the socio-political upheaval in neighbouring Arab countries. Edited by Rouzbeh Parsi Edited by Rouzbeh Parsi, the volume features contributions from five authors who are all specialists in various aspects of Iranian politics and society. Each Edited by Rouzbeh Parsi by RouzbehEdited Parsi Chaillot Papers | February 2012 author explores some of the most crucial variables of the Iranian body politic. Their focus on distinct dimensions of Iranian society and culture casts light on the changes afoot in contemporary Iran and how the political elite controlling the state respond to these challenges. ISBN 978-92-9198-198-4 published by phone: + 33 (0) 1 56 89 19 30 ISSN 1017-7566 the European Union fax: + 33 (0) 1 56 89 19 31 QN-AA-12-128-EN-C Institute for Security Studies e-mail: [email protected] doi:10.2815/27423 100, avenue de Suffren www.iss.europa.eu PAPER CHAILLOT 75015 Paris - France 128 128 CHAILLOT PAPERS BOOKS In January 2002 the Institute for Security Studies (EUISS) became an 127 120 2010 QUELLE DÉFENSE EUROPÉENNE autonomous Paris-based agency of the European Union. -

Propaganda Techniques: a Discourse Analysis of Resalat and Etemad-E Melli Editorials

PROPAGANDA TECHNIQUES: A DISCOURSE ANALYSIS OF RESALAT AND ETEMAD-E MELLI EDITORIALS SEYEDALI JAVADI THESIS SUBMITTED IN FULFILMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY FACULTY OF ARTS AND SOCIAL SCIENCES UNIVERSITY OF MALAYA KUALA LUMPUR 2017 UNIVERSITY OF MALAYA ORIGINAL LITERARY WORK DECLARATION Name of Candidate: SEYEDALI JAVADI (I.C / Passport No: U25223105) Registration / Matric No: AHA090043 Name of Degree: DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Title of Project Paper / Research Report / Dissertation / Thesis (“this Work”): “PROPAGANDA TECHNIQUES: A DISCOURSE ANALYSIS OF RESALAT AND ETEMAD-E MELLI EDITORIALS” Field of Study: NEWSPAPER MEDIA I do solemnly and sincerely declare that: (1) I am the sole author / writer of this Work; (2) This Work is original; (3) Any use of any work in which copyright exists was done by way of fair dealing and for permitted purposes and any excerpt or extract from, or reference to or reproduction of any copyright work has been disclosed expressly and sufficiently and the title of the Work and its authorship have been acknowledged in this Work; (4) I do not have any actual knowledge nor do I ought reasonably to know that the making of this work constitutes an infringement of any copyright work; (5) I hereby assign all and every rights in the copyright to this Work to the University of Malaya (“UM”), who henceforth shall be owner of the copyright in this Work and that any reproduction or use in any form or by any means whatsoever is prohibited without the written consent of UM having been first had and obtained; (6) I am fully aware that if in the course of making this Work I have infringed any copyright whether intentionally or otherwise, I may be subject to legal action or any other action as may be determined by UM.