Reform Versus Radicalism in the Islamic Republic

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The IRGC in the Age of Ebrahim Raisi: Decision-Making and Factionalism in Iran’S Revolutionary Guard

The IRGC in the Age of Ebrahim Raisi: Decision-Making and Factionalism in Iran’s Revolutionary Guard SAEID GOLKAR AUGUST 2021 KASRA AARABI Contents Executive Summary 4 The Raisi Administration, the IRGC and the Creation of a New Islamic Government 6 The IRGC as the Foundation of Raisi’s Islamic Government The Clergy and the Guard: An Inseparable Bond 16 No Coup in Sight Upholding Clerical Superiority and Preserving Religious Legitimacy The Importance of Understanding the Guard 21 Shortcomings of Existing Approaches to the IRGC A New Model for Understanding the IRGC’s Intra-elite Factionalism 25 The Economic Vertex The Political Vertex The Security-Intelligence Vertex Charting IRGC Commanders’ Positions on the New Model Shades of Islamism: The Ideological Spectrum in the IRGC Conclusion 32 About the Authors 33 Saeid Golkar Kasra Aarabi Endnotes 34 4 The IRGC in the Age of Ebrahim Raisi Executive Summary “The Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps [IRGC] has excelled in every field it has entered both internationally and domestically, including security, defence, service provision and construction,” declared Ayatollah Ebrahim Raisi, then chief justice of Iran, in a speech to IRGC commanders on 17 March 2021.1 Four months on, Raisi, who assumes Iran’s presidency on 5 August after the country’s June 2021 election, has set his eyes on further empowering the IRGC with key ministerial and bureaucratic positions likely to be awarded to guardsmen under his new government. There is a clear reason for this ambition. Expanding the power of the IRGC serves the interests of both Raisi and his 82-year-old mentor, Ayatollah Ali Khamenei, the supreme leader of the Islamic Republic. -

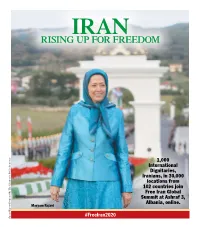

Rising up for Freedom

IRAN RISING UP FOR FREEDOM 1,000 International Dignitaries, Iranians, in 30,000 locations from 102 countries join Free Iran Global Summit at Ashraf 3, Albania, online. Maryam Rajavi #FreeIran2020 Special Report Sponsored The by Alliance Public for Awareness Iranian dissidents rally for regime change in Tehran BY BEN WOLFGANG oppressive government that has ruled Iran from both political parties participating has proven it can’t deliver for its people. tHe WasHInGtOn tImes since the Islamic Revolution of 1979. Leaders represented a who’s who list of American “The Iranian people want change, to of the NCRI, which is comprised of multiple “formers,” including former Sen. Joseph I. have democracy, finally to have human Iran’s theocracy is at the weakest point other organizations, say the council has seen Lieberman of Connecticut, former Penn- rights, to finally have economic wealth, of its four-decade history and facing un- its stature grow to the point that Iranian sylvania Gov. Tom Ridge, former Attorney no more hunger. The will of the people precedented challenges from a courageous officials can no longer deny its influence. General Michael Mukasey, retired Marine is much stronger than any oppressive citizenry hungry for freedom, Iranian dis- The NCRI has many American support- Commandant James T. Conway and others. measure of an Iranian regime,” said Martin sidents and prominent U.S. and European ers, including some with close relationships Several current U.S. officials also delivered Patzelt, a member of German Parliament. politicians said Friday at a major interna- to Mr. Trump, such as former New York remarks, including Sen. -

Iran, Gulf Security, and U.S. Policy

Iran, Gulf Security, and U.S. Policy Kenneth Katzman Specialist in Middle Eastern Affairs August 14, 2015 Congressional Research Service 7-5700 www.crs.gov RL32048 Iran, Gulf Security, and U.S. Policy Summary Since the Islamic Revolution in Iran in 1979, a priority of U.S. policy has been to reduce the perceived threat posed by Iran to a broad range of U.S. interests, including the security of the Persian Gulf region. In 2014, a common adversary emerged in the form of the Islamic State organization, reducing gaps in U.S. and Iranian regional interests, although the two countries have often differing approaches over how to try to defeat the group. The finalization on July 14, 2015, of a “Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action” (JCPOA) between Iran and six negotiating powers could enhance Iran’s ability to counter the United States and its allies in the region, but could also pave the way for cooperation to resolve some of the region’s several conflicts. During the 1980s and 1990s, U.S. officials identified Iran’s support for militant Middle East groups as a significant threat to U.S. interests and allies. A perceived potential threat from Iran’s nuclear program emerged in 2002, and the United States orchestrated broad international economic pressure on Iran to try to ensure that the program is verifiably confined to purely peaceful purposes. The international pressure contributed to the June 2013 election as president of Iran of the relatively moderate Hassan Rouhani, who campaigned as an advocate of ending Iran’s international isolation. -

Mullahs, Guards, and Bonyads: an Exploration of Iranian Leadership

THE ARTS This PDF document was made available CHILD POLICY from www.rand.org as a public service of CIVIL JUSTICE the RAND Corporation. EDUCATION ENERGY AND ENVIRONMENT Jump down to document6 HEALTH AND HEALTH CARE INTERNATIONAL AFFAIRS The RAND Corporation is a nonprofit NATIONAL SECURITY research organization providing POPULATION AND AGING PUBLIC SAFETY objective analysis and effective SCIENCE AND TECHNOLOGY solutions that address the challenges SUBSTANCE ABUSE facing the public and private sectors TERRORISM AND HOMELAND SECURITY around the world. TRANSPORTATION AND INFRASTRUCTURE Support RAND WORKFORCE AND WORKPLACE Purchase this document Browse Books & Publications Make a charitable contribution For More Information Visit RAND at www.rand.org Explore the RAND National Defense Research Institute View document details Limited Electronic Distribution Rights This document and trademark(s) contained herein are protected by law as indicated in a notice appearing later in this work. This electronic representation of RAND intellectual property is provided for non-commercial use only. Unauthorized posting of RAND PDFs to a non-RAND Web site is prohibited. RAND PDFs are protected under copyright law. Permission is required from RAND to reproduce, or reuse in another form, any of our research documents for commercial use. For information on reprint and linking permissions, please see RAND Permissions. This product is part of the RAND Corporation monograph series. RAND monographs present major research findings that address the challenges facing the public and private sectors. All RAND mono- graphs undergo rigorous peer review to ensure high standards for research quality and objectivity. Mullahs, Guards, and Bonyads An Exploration of Iranian Leadership Dynamics David E. -

Blood-Soaked Secrets Why Iran's 1988 Prison

BLOOD-SOAKED SECRETS WHY IRAN’S 1988 PRISON MASSACRES ARE ONGOING CRIMES AGAINST HUMANITY Amnesty International is a global movement of more than 7 million people who campaign for a world where human rights are enjoyed by all. Our vision is for every person to enjoy all the rights enshrined in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and other international human rights standards. We are independent of any government, political ideology, economic interest or religion and are funded mainly by our membership and public donations. © Amnesty International 2017 Except where otherwise noted, content in this document is licensed under a Creative Commons Cover photo: Collage of some of the victims of the mass prisoner killings of 1988 in Iran. (attribution, non-commercial, no derivatives, international 4.0) licence. © Amnesty International https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/legalcode For more information please visit the permissions page on our website: www.amnesty.org Where material is attributed to a copyright owner other than Amnesty International this material is not subject to the Creative Commons licence. First published in 2017 by Amnesty International Ltd Peter Benenson House, 1 Easton Street London WC1X 0DW, UK Index: MDE 13/9421/2018 Original language: English amnesty.org CONTENTS GLOSSARY 7 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 8 METHODOLOGY 18 2.1 FRAMEWORK AND SCOPE 18 2.2 RESEARCH METHODS 18 2.2.1 TESTIMONIES 20 2.2.2 DOCUMENTARY EVIDENCE 22 2.2.3 AUDIOVISUAL EVIDENCE 23 2.2.4 COMMUNICATION WITH IRANIAN AUTHORITIES 24 2.3 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS 25 BACKGROUND 26 3.1 PRE-REVOLUTION REPRESSION 26 3.2 POST-REVOLUTION REPRESSION 27 3.3 IRAN-IRAQ WAR 33 3.4 POLITICAL OPPOSITION GROUPS 33 3.4.1 PEOPLE’S MOJAHEDIN ORGANIZATION OF IRAN 33 3.4.2 FADAIYAN 34 3.4.3 TUDEH PARTY 35 3.4.4 KURDISH DEMOCRATIC PARTY OF IRAN 35 3.4.5 KOMALA 35 3.4.6 OTHER GROUPS 36 4. -

Revolutionary Ayatollah: How My Father Went from the Prison of the Shah to the Prison of Khamenei

MENU Policy Analysis / Articles & Op-Eds Revolutionary Ayatollah: How My Father Went from the Prison of the Shah to the Prison of Khamenei Jan 20, 2010 Articles & Testimony n the very cold winter of 1979, Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini, the founder of the Islamic Republic of Iran, I returned to Qom, the spiritual capital of the Shiite world, for the first time after his long exile. A huge crowd came out that day. As he made his way to the stage, passing through those who pressed together to see him, the ayatollah's mantle fell off. Once he had settled in his chair, he noticed how chilly he was. "I'm cold," he said. Within seconds, another mantle fell over his shoulders and wrapped him warm. This mantle belonged to my father, Mohammad Taghi Khalaji. After my father draped his mantle over Ayatollah Khomeini's shoulders, he went to the podium and gave the introductory speech on behalf of the clerical establishment, as well as the people of Qom. I never saw my father with that mantle again. Right now, my father is in solitary confinement in Evin prison in Tehran. He was arrested in his home in Qom on Jan. 12. On that day, he joined hundreds of Iranian citizens who have been arrested by the Iranian regime after the rigged election in June 2009. My family has been given no information -- either by the Special Court of Clerics or by the Ministry of Intelligence -- about any charges against my father. Furthermore, my father has not been allowed to contact us or hire a lawyer. -

Beyond Borders the Expansionist Ideology of Iran's Islamic

Beyond Borders The Expansionist Ideology of Iran’s Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps KASRA AARABI FEBRUARY 2020 Contents Executive Summary 5 The Approach: Understanding the IRGC Training Materials 7 Key Findings 7 Policy Recommendations 8 Introduction 11 A Common Ideology 14 Our Approach 15 Background – The Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps 17 Indoctrination: An Increasing Focal Point for the IRGC 19 Inside the IRGC’s Ideological Training Programme 25 Objectives: The Grand Vision 27 Group Identity: Defining the ‘Ingroup' 31 Conduct: Actions Permissible and Necessary 36 The Enemy: Defining the ‘Outgroup’ 44 Conclusion 53 Endnotes 55 Appendix 67 3 4 Executive Summary Unlike the Iranian army that protects Iran’s borders, the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC) is mandated by Iran’s constitution to pursue “an ideological mission of jihad in God’s way; that is extending sovereignty of God’s law throughout the world.”1 Since the inception of this paramilitary force in 1979, the Guard has emerged as the principal organisation driving the Iranian regime’s revolutionary Shia Islamist ideology, within and beyond the regime’s borders. Over these 40 years, it has been linked to terrorist attacks, hostage-takings, maritime piracy, political assassinations, human rights violations and the crushing of domestic dissent across Iran, most recently with bloodshed on the Iranian streets in November 2019, leaving 1,500 people dead in less than two weeks.2 Today, the IRGC remains Lebanese Hizbullah’s prime benefactor, with the Guard known to be providing arms, training and funding to sustain the group’s hostile presence against Israel and its grip on Lebanese society, and key operational assistance that has resulted in attacks on civilians stretching from Argentina, Bulgaria to Thailand. -

National Subway Train Developed Despite Sanctions

WWW.TEHRANTIMES.COM I N T E R N A T I O N A L D A I L Y 8 Pages Price 50,000 Rials 1.00 EURO 4.00 AED 42nd year No.13904 Sunday MARCH 14, 2021 Esfand 24, 1399 Rajab 30, 1442 Persons with military Skocic protests AFC over Free medical services “The Sand Wolf” background can stand choosing Bahrain as for people aged hunts Iran’s Flying as candidates Page 2 Group C host Page 3 over 65 Page 7 Turtle Page 8 Iranian heavy crude oil price rises 11.5% in February: OPEC TEHRAN- Iranian heavy oil price increased in the previous year’s same period. $6.28 in February to register an 11.5-per- The report put Iranian crude output for Illogical presence cent rise compared to the previous month, February at 2.12 million barrels per day according to OPEC’s latest monthly report. indicating a 35,000-bpd increase compared See page 3 Iran sold its heavy crude oil at $60.66 to the figure for the previous month. U.S. faces trouble justifying presence in Iraq per barrel in the mentioned month, com- Based on OPEC data, the country’s av- pared to January’s $54.38 per barrel, IRIB erage crude output in the fourth quarter reported. of 2020 stood at 1.993 million barrels According to the report, the country’s per day indicating a near 45,000-bpd average heavy crude price was $57.52 from rise compared to the figure for the third the beginning of 2021 up to the report’s quarter of the year. -

Report Worldwide Cultural Differences

Worldwide cultural differences in socio-ethical views in relation to biotechnology A report commissioned by the COGEM (Netherlands Commission on Genetic Modification) Dr. Henk van den Belt Prof. Dr. Jozef Keulartz April, 2007 This report was commissioned by COGEM. The contents of this publication are the sole responsibility of the authors. The contents of this publication may in no way be taken to represent the views of COGEM. Dit rapport is in opdracht van de Commissie Genetische Modificatie (COGEM) samengesteld. De meningen die in het rapport worden weergegeven zijn die van de auteurs en weerspiegelen niet noodzakelijkerwijs de mening van de COGEM. 2 Contents Voorwoord/Preface …………………5 Chapter 1 Worldwide cultural differences in socio-ethical views in relation to biotechnology: Overview and summary ……………………..7 Chapter 2 Monsters, boundary work and framing: Biotechnology from an anthropological perspective …………………….27 Chapter 3 Hwang Woo Suk and the Korean stem cell debacle: Scientific fraud, techno-nationalism and the ‘Wild East’ ……………………..47 Chapter 4 East Asia and the “GM Cold War”: The international struggle over precaution, labelling and segregation ………….77 3 4 Voorwoord/Preface Het voorliggende rapport Worldwide Cultural Differences in Socio-Ethical Views in Relation to Biotechnology (Mondiale cultuurverschillen in de ethisch maatschappelijke opvattingen i.v.m. biotechnologie) is samengesteld in opdracht van de Commissie Genetische Modificatie (COGEM). Het is mede bedoeld ter voorbereiding van de nieuwe Trendanalyse Biotechnologie die in 2007 zal worden uitgebracht. De onderzoekswerkzaamheden (voornamelijk ‘desk research’) zijn verricht door dr. Henk van den Belt onder directe supervisie van Prof. dr. Jozef Keulartz. De uitvoering van het project is begeleid door een begeleidingscommissie waarin Prof. -

The Iranian Cultural and Natural Heritage Year Friday, 14 March 2008

The Iranian Cultural and Natural Heritage Year Friday, 14 March 2008 http://www.amilimani.com/index.php?option=com_content&task=view&id=100&Itemid=2 According to the World Encyclopedia, cultural genocide is a term used to describe the deliberate destruction of the cultural heritage of a people or nation for political or military reasons. Since coming to power twenty-nine years ago, the Islamic Republic of Iran has been in a constant battle with the Iranian people as well as her culture and heritage. Over its life span, the Islamic Republic zealots have tried innumerable times to cleanse the pre-Islamic Persian heritage in the name of Islam. First, they declared war against the Persian New Year or “Nowruz”, and then, they attacked other Persian traditions and customs. In 1979, Khomeini's right-hand man, the Ayatollah Sadegh Khalkhali, tried to bulldoze Iran’s greatest epical poet Ferdowsi's tomb and Persepolis palace. Fortunately, the total bulldozing of the relics of the palace was averted by Iranian patriots who wished to preserve their heritage; who literally stood in front of the bulldozers and did not allow the destruction of this heritage of humanity. The Islamic Republic of Iran, which holds in great contempt any non-Islamic belief or heritage, has embarked on destroying many pre-Islamic archeological sites in Iran such as Pasargad and Persepolis -- some of humanity's most prized cultural heritage, on the pretext of building a dam. The heinous destruction of the two Buddha statues by Afghanistan's Taliban pales in comparison to the present barbaric designs of the Islamic Republic. -

13881 Saturday FEBRUARY 13, 2021 Bahman 25, 1399 Rajab 1, 1442

WWW.TEHRANTIMES.COM I N T E R N A T I O N A L D A I L Y 8 Pages Price 50,000 Rials 1.00 EURO 4.00 AED 42nd year No.13881 Saturday FEBRUARY 13, 2021 Bahman 25, 1399 Rajab 1, 1442 Ghalibaf: Iran’s strategic Ali Moradi Iran sits at UN TIR Even ‘illegal migrants’ principle is to develop nominated for executive board for 3rd in Iran will get ties with China Page 2 IWF presidency Page 3 consecutive time Page 4 COVID-19 vaccine Page 7 Iran’s top judge holds talks with Iraqi leaders SPECIAL ISSUE TEHRAN - Iran’s Judiciary Chief Ebra- him Raeisi held talks with several Iraqi political and judicial leaders including President Barham Salih, Prime Min- ister Mustafa al-Kadhimi, and Head of Iraq’s Supreme Judicial Council Faiq Zaidan. The man of On Monday, February 8, Ayatollah Raisi paid a two-day visit to Iraq. During his meeting with his Iraqi counterpart, the two sides signed three memoranda of understanding to boost judicial and legal cooperation between the two neighboring countries. theoretical Continued on page 3 Bandar Abbas-Latakia direct shipping line to be launched by early Mar. battlefields TEHRAN - Iran is going to establish a direct shipping line between its south- ern port of Bandar Abbas and Syria’s Mediterranean port of Latakia on March In memory of Ayatollah 10, Head of Iran-Syria Joint Chamber of Commerce Keyvan Kashefi announced. Mohammad Taghi Continued on page 4 Mesbah Yazdi, the Iranian “Yadoo” tops at 39th renowned theorist and Fajr Film Fsetival philosopher TEHRAN – War drama “Yadoo” was the top winner of the 39th Fajr Film Festival by garnering awards in several categories, including best film and best director. -

POWER VERSUS CHOICE Human Rights and Parliamentary Elections in the Islamic Republic of Iran

Iran Page 1 of 10 March 1996 Vol. 8, No. 1 (E) IRAN POWER VERSUS CHOICE Human Rights and Parliamentary Elections in the Islamic Republic of Iran SUMMARY Iranians will vote on March 8, 1996, to elect 270 members of the parliament, or Majles, in an election process that severely limits citizen participation. Parliamentary elections could represent a real contest for power in Iran's political system-but only if arbitrary bans on candidates and other constraints on political life are lifted. As the campaign period opened on March 1, the government-appointed Council of Guardians had excluded some 44 percent of the more than 5,000 candidates on the basis of discriminatory and arbitrary criteria, significantly impairing access to the political process and citizens' freedom of choice. The council vetoed candidates by calling into question such matters as their commitment to the political system, their loyalty, and their "practical adherence to Islam," or their support for the principle of rule by the pre-eminent religious jurist (velayat-e faqih). At the invitation of the Iranian government, Human Rights Watch was able to travel to Iran in early 1996 to investigate and discuss the human rights dimension of Iran's political process, and in particular the guarantees and restraints placed upon international standards of freedom of expression, association and assembly during the pre-election period. During this unprecedented three-week mission Human Rights Watch/Middle East interviewed dozens of political activists, lawyers, parliamentarians, writers, journalists, senior European diplomats and government officials in Tehran and Isfahan. Although denied permission to visit the city of Qom, where leading clerical critics of the government are imprisoned, Human Rights Watch was otherwise allowed broad access, including a private meeting with one of the longest-term political prisoners still in detention, former Deputy Prime Minister Abbas Amir Entezam.