Understanding Iran: Attempts at Unravelling the Structures That Determine Iranian State Behaviour

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The IRGC in the Age of Ebrahim Raisi: Decision-Making and Factionalism in Iran’S Revolutionary Guard

The IRGC in the Age of Ebrahim Raisi: Decision-Making and Factionalism in Iran’s Revolutionary Guard SAEID GOLKAR AUGUST 2021 KASRA AARABI Contents Executive Summary 4 The Raisi Administration, the IRGC and the Creation of a New Islamic Government 6 The IRGC as the Foundation of Raisi’s Islamic Government The Clergy and the Guard: An Inseparable Bond 16 No Coup in Sight Upholding Clerical Superiority and Preserving Religious Legitimacy The Importance of Understanding the Guard 21 Shortcomings of Existing Approaches to the IRGC A New Model for Understanding the IRGC’s Intra-elite Factionalism 25 The Economic Vertex The Political Vertex The Security-Intelligence Vertex Charting IRGC Commanders’ Positions on the New Model Shades of Islamism: The Ideological Spectrum in the IRGC Conclusion 32 About the Authors 33 Saeid Golkar Kasra Aarabi Endnotes 34 4 The IRGC in the Age of Ebrahim Raisi Executive Summary “The Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps [IRGC] has excelled in every field it has entered both internationally and domestically, including security, defence, service provision and construction,” declared Ayatollah Ebrahim Raisi, then chief justice of Iran, in a speech to IRGC commanders on 17 March 2021.1 Four months on, Raisi, who assumes Iran’s presidency on 5 August after the country’s June 2021 election, has set his eyes on further empowering the IRGC with key ministerial and bureaucratic positions likely to be awarded to guardsmen under his new government. There is a clear reason for this ambition. Expanding the power of the IRGC serves the interests of both Raisi and his 82-year-old mentor, Ayatollah Ali Khamenei, the supreme leader of the Islamic Republic. -

Iran's Nuclear Ambitions From

IDENTITY AND LEGITIMACY: IRAN’S NUCLEAR AMBITIONS FROM NON- TRADITIONAL PERSPECTIVES Pupak Mohebali Doctor of Philosophy University of York Politics June 2017 Abstract This thesis examines the impact of Iranian elites’ conceptions of national identity on decisions affecting Iran's nuclear programme and the P5+1 nuclear negotiations. “Why has the development of an indigenous nuclear fuel cycle been portrayed as a unifying symbol of national identity in Iran, especially since 2002 following the revelation of clandestine nuclear activities”? This is the key research question that explores the Iranian political elites’ perspectives on nuclear policy actions. My main empirical data is elite interviews. Another valuable source of empirical data is a discourse analysis of Iranian leaders’ statements on various aspects of the nuclear programme. The major focus of the thesis is how the discourses of Iranian national identity have been influential in nuclear decision-making among the national elites. In this thesis, I examine Iranian national identity components, including Persian nationalism, Shia Islamic identity, Islamic Revolutionary ideology, and modernity and technological advancement. Traditional rationalist IR approaches, such as realism fail to explain how effective national identity is in the context of foreign policy decision-making. I thus discuss the connection between national identity, prestige and bargaining leverage using a social constructivist approach. According to constructivism, states’ cultures and identities are not established realities, but the outcomes of historical and social processes. The Iranian nuclear programme has a symbolic nature that mingles with socially constructed values. There is the need to look at Iran’s nuclear intentions not necessarily through the lens of a nuclear weapons programme, but rather through the regime’s overall nuclear aspirations. -

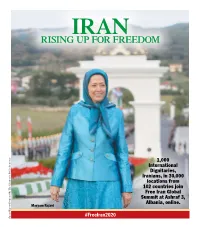

Rising up for Freedom

IRAN RISING UP FOR FREEDOM 1,000 International Dignitaries, Iranians, in 30,000 locations from 102 countries join Free Iran Global Summit at Ashraf 3, Albania, online. Maryam Rajavi #FreeIran2020 Special Report Sponsored The by Alliance Public for Awareness Iranian dissidents rally for regime change in Tehran BY BEN WOLFGANG oppressive government that has ruled Iran from both political parties participating has proven it can’t deliver for its people. tHe WasHInGtOn tImes since the Islamic Revolution of 1979. Leaders represented a who’s who list of American “The Iranian people want change, to of the NCRI, which is comprised of multiple “formers,” including former Sen. Joseph I. have democracy, finally to have human Iran’s theocracy is at the weakest point other organizations, say the council has seen Lieberman of Connecticut, former Penn- rights, to finally have economic wealth, of its four-decade history and facing un- its stature grow to the point that Iranian sylvania Gov. Tom Ridge, former Attorney no more hunger. The will of the people precedented challenges from a courageous officials can no longer deny its influence. General Michael Mukasey, retired Marine is much stronger than any oppressive citizenry hungry for freedom, Iranian dis- The NCRI has many American support- Commandant James T. Conway and others. measure of an Iranian regime,” said Martin sidents and prominent U.S. and European ers, including some with close relationships Several current U.S. officials also delivered Patzelt, a member of German Parliament. politicians said Friday at a major interna- to Mr. Trump, such as former New York remarks, including Sen. -

Elections in Iran 2017 Presidential and Municipal Elections

Elections in Iran 2017 Presidential and Municipal Elections Frequently Asked Questions Middle East and North Africa International Foundation for Electoral Systems 2011 Crystal Drive | Floor 10 | Arlington, VA 22202 | www.IFES.org May 15, 2017 Frequently Asked Questions When is Election Day? ................................................................................................................................... 1 Who will Iranians elect on May 19? .............................................................................................................. 1 What is the Guardian Council, and what is its mandate in Iran’s electoral process? ................................... 1 What is the Central Executive Election Board? What is its mandate? ......................................................... 2 What is the legal framework for elections in Iran? ...................................................................................... 2 What does the Law on Presidential Elections entail? ................................................................................... 3 What electoral system is used in Iran? ......................................................................................................... 3 Who is eligible to vote?................................................................................................................................. 3 Who can stand as a presidential candidate? ................................................................................................ 4 How is election -

Iran COI Compilation September 2013

Iran COI Compilation September 2013 ACCORD is co-funded by the European Refugee Fund, UNHCR and the Ministry of the Interior, Austria. Commissioned by the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees, Division of International Protection. UNHCR is not responsible for, nor does it endorse, its content. Any views expressed are solely those of the author. ACCORD - Austrian Centre for Country of Origin & Asylum Research and Documentation Iran COI Compilation September 2013 This report serves the specific purpose of collating legally relevant information on conditions in countries of origin pertinent to the assessment of claims for asylum. It is not intended to be a general report on human rights conditions. The report is prepared on the basis of publicly available information, studies and commentaries within a specified time frame. All sources are cited and fully referenced. This report is not, and does not purport to be, either exhaustive with regard to conditions in the country surveyed, or conclusive as to the merits of any particular claim to refugee status or asylum. Every effort has been made to compile information from reliable sources; users should refer to the full text of documents cited and assess the credibility, relevance and timeliness of source material with reference to the specific research concerns arising from individual applications. © Austrian Red Cross/ACCORD An electronic version of this report is available on www.ecoi.net. Austrian Red Cross/ACCORD Wiedner Hauptstraße 32 A- 1040 Vienna, Austria Phone: +43 1 58 900 – 582 E-Mail: [email protected] Web: http://www.redcross.at/accord ACCORD is co-funded by the European Refugee Fund, UNHCR and the Ministry of the Interior, Austria. -

The Veiling Issue in 20Th Century Iran in Fashion and Society, Religion, and Government

Article The Veiling Issue in 20th Century Iran in Fashion and Society, Religion, and Government Faegheh Shirazi Department of Middle Eastern Studies, The University of Texas at Austin, Austin, TX 78712, USA; [email protected] Received: 7 May 2019; Accepted: 30 July 2019; Published: 1 August 2019 Abstract: This essay focuses on the Iranian woman’s veil from various perspectives including cultural, social, religious, aesthetic, as well as political to better understand this object of clothing with multiple interpretive meanings. The veil and veiling are uniquely imbued with layers of meanings serving multiple agendas. Sometimes the function of veiling is contradictory in that it can serve equally opposing political agendas. Keywords: Iran; women’s right; veiling; veiling fashion; Iranian politics Iran has a long history of imposing rules about what women can and cannot wear, in addition to so many other forms of discriminatory laws against women that violate human rights. One of the most recent protests (at Tehran University) against the compulsory hijab1 was also meant to unite Iranians of diverse backgrounds to show their dissatisfaction with the government. For the most part, the demonstration was only a hopeful attempt for change. In one tweet from Iran [at Tehran University] we read in Persian: When Basijis [who receive their orders from the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC) and the Supreme Leader of Iran] did not give permission to the students to present a talk against compulsory hijab, the students started to sing together the iconic poem of yar e ,my school friend2. “Basij members became helpless and nervous/ﻳﺎﺭ ﺩﺑﺴﺘﺎﻧﯽ ﻣﻦ dabestani man but the students sang louder and louder. -

Islamic Republic of Iran (Persian)

Coor din ates: 3 2 °N 5 3 °E Iran Irān [ʔiːˈɾɒːn] ( listen)), also known اﯾﺮان :Iran (Persian [11] [12] Islamic Republic of Iran as Persia (/ˈpɜːrʒə/), officially the Islamic (Persian) ﺟﻣﮫوری اﺳﻼﻣﯽ اﯾران Jomhuri-ye ﺟﻤﮭﻮری اﺳﻼﻣﯽ اﯾﺮان :Republic of Iran (Persian Eslāmi-ye Irān ( listen)),[13] is a sovereign state in Jomhuri-ye Eslāmi-ye Irān Western Asia.[14][15] With over 81 million inhabitants,[7] Iran is the world's 18th-most-populous country.[16] Comprising a land area of 1,648,195 km2 (636,37 2 sq mi), it is the second-largest country in the Middle East and the 17 th-largest in the world. Iran is Flag Emblem bordered to the northwest by Armenia and the Republic of Azerbaijan,[a] to the north by the Caspian Sea, to the Motto: اﺳﺗﻘﻼل، آزادی، ﺟﻣﮫوری اﺳﻼﻣﯽ northeast by Turkmenistan, to the east by Afghanistan Esteqlāl, Āzādi, Jomhuri-ye Eslāmi and Pakistan, to the south by the Persian Gulf and the Gulf ("Independence, freedom, the Islamic of Oman, and to the west by Turkey and Iraq. The Republic") [1] country's central location in Eurasia and Western Asia, (de facto) and its proximity to the Strait of Hormuz, give it Anthem: ﺳرود ﻣﻠﯽ ﺟﻣﮫوری اﺳﻼﻣﯽ اﯾران geostrategic importance.[17] Tehran is the country's capital and largest city, as well as its leading economic Sorud-e Melli-ye Jomhuri-ye Eslāmi-ye Irān ("National Anthem of the Islamic Republic of Iran") and cultural center. 0:00 MENU Iran is home to one of the world's oldest civilizations,[18][19] beginning with the formation of the Elamite kingdoms in the fourth millennium BCE. -

Iran Iran Presidential Elections June 2020

Iranian Presidential Election IRAN IRAN PRESIDENTIAL ELECTIONS JUNE 2020 solaceglobal.com Page 0 Iranian Presidential Election Iran Presidential Election Executive Summary The 18 June saw Iran hold presidential elections. The election was marred in the eyes of many before they were even held, with the majority of candidates barred from running. This resulted in many believing the election was rigged to give one favoured candidate, Ebrahim Raisi, victory. Raisi, who is currently the country’s Chief Justice, won the election with nearly 62 percent of the vote. Raisi has been accused of large-scale human rights abuses in the past and is nicknamed the “Butcher of Tehran”. In addition to now being the president-elect, he is tipped as a potential successor to Supreme Leader Khamenei. He has support among Iran’s hard-liners, close links to the clerical establishment and, importantly, the Revolutionary Guard. Thus, the election of Raisi can be viewed as an important step by these groups to realise control over the country after several years of governance by a moderate reformist President. Under a Raisi presidency, Iranian politics is likely to become more repressive. There will be little change in the country’s wider foreign policy under him. Despite this, there is still a moderate likelihood that a new nuclear agreement can be reached with the US and other Western countries, as the lifting of sanctions would be beneficial to the Iranian establishment and wider domestic economy. Presidential Profile Ebrahim Raisi is supported by the hard-line and conservative factions of Iranian politics. He was born to a clerical family in the holy city of Mashhad and is purported to be a descendent of the Prophet Mohammad. -

Discussion Guide for “The Iranian Revolution” a Video Interview with Dr

DISCUSSION GUIDE FOR “THE IRANIAN REVOLUTION” a video interview with Dr. Abbas Milani Organizing • What is a revolution? Questions • What were the successes and failures of the Iranian Revolution? • How did the Iranian Revolution impact or contribute to events in the Middle East, the United States, and the world? • How is the Iranian Revolution similar and different from other revolutions? • What are some of the challenges of writing about a historical event like the Iranian Revolution? Summary In this video, Professor Abbas Milani discusses Iran and the Iranian Revolution, noting the influence of Iran regionally and in the United States, the significance and impact of the Iranian Revolution, and the Iranian Revolution’s causes and effects. He also emphasizes the fight for democracy throughout Iran’s history of revolutions and today. Objectives During and after viewing this video, students will: • gain a general understanding of the course of the Iranian Revolution and the events leading up to it; • examine the definition of revolution and compare the Iranian Revolution with other revolutions; • analyze the significance and impact of the Iranian Revolution in history and today; and • understand the complexities and multiple perspectives of history. “IRANIAN REVOLUTION” DISCUSSION GUIDE 1 introduction Materials Handout 1, Background Guide—Iranian Revolution, pp. 5–9, 30 copies Handout 2, Video Notes, p. 10, 30 copies Handout 3, Connection—Iran Today, pp. 11–12, 5 copies Projection 1, Discussion—What is a revolution?, p. 13 Projection 2, Wrap-up Discussion, p. 14 Answer Key 1, Video Notes, pp. 15–16 Answer Key 2, Connection—Iran Today, pp. -

Notes on Iran

Iran: Some Basic Facts Useful Terms: Shah-King Faqih-Supreme leader Majlis-Parliament Republic-A state in which the political leader is not a monarch or other hereditary head of state. In modern times the leader is usually a president. Theocratic Republic-A system of government in which the leader of the government is thought to have divine guidance. Official Language: Western Farsi (also called Persian) many more spoken Population: 72,048,000 67% urban, 33 % rural (1996 census) Government: Theocratic Republic Religion About 99 percent of the Iranian people are Muslims. About 95 percent of them belong to the Shi`ah branch of Islam, which is the state religion of Iran. Most of the rest belong to the Sunni branch. Iran’s largest religious minority is the Baha’is. Consisting of about 250,000 Iranis, the Baha'is have never had legal recognition in Iran and are forbidden to practice their faith. Iran also has some Christians, Jews, and Zoroastrianians (followers of an ancient Persian religion.) The Islamic government has little tolerance for Iran's religious minorities. Baha'is in particular have been severely persecuted. Way of Life The Islamic government strongly influences the Iranian way of life. It restricts freedom of speech and other civil rights. Islamic clergymen hold many key positions in government, and all perspective candidates for governmental positions must be approved by the government prior to running for office. All laws are reviewed by the government to ensure they don’t violate Islamic law. All judges on the Supreme Court are members of the Islamic clergy. -

National Subway Train Developed Despite Sanctions

WWW.TEHRANTIMES.COM I N T E R N A T I O N A L D A I L Y 8 Pages Price 50,000 Rials 1.00 EURO 4.00 AED 42nd year No.13904 Sunday MARCH 14, 2021 Esfand 24, 1399 Rajab 30, 1442 Persons with military Skocic protests AFC over Free medical services “The Sand Wolf” background can stand choosing Bahrain as for people aged hunts Iran’s Flying as candidates Page 2 Group C host Page 3 over 65 Page 7 Turtle Page 8 Iranian heavy crude oil price rises 11.5% in February: OPEC TEHRAN- Iranian heavy oil price increased in the previous year’s same period. $6.28 in February to register an 11.5-per- The report put Iranian crude output for Illogical presence cent rise compared to the previous month, February at 2.12 million barrels per day according to OPEC’s latest monthly report. indicating a 35,000-bpd increase compared See page 3 Iran sold its heavy crude oil at $60.66 to the figure for the previous month. U.S. faces trouble justifying presence in Iraq per barrel in the mentioned month, com- Based on OPEC data, the country’s av- pared to January’s $54.38 per barrel, IRIB erage crude output in the fourth quarter reported. of 2020 stood at 1.993 million barrels According to the report, the country’s per day indicating a near 45,000-bpd average heavy crude price was $57.52 from rise compared to the figure for the third the beginning of 2021 up to the report’s quarter of the year. -

Report Worldwide Cultural Differences

Worldwide cultural differences in socio-ethical views in relation to biotechnology A report commissioned by the COGEM (Netherlands Commission on Genetic Modification) Dr. Henk van den Belt Prof. Dr. Jozef Keulartz April, 2007 This report was commissioned by COGEM. The contents of this publication are the sole responsibility of the authors. The contents of this publication may in no way be taken to represent the views of COGEM. Dit rapport is in opdracht van de Commissie Genetische Modificatie (COGEM) samengesteld. De meningen die in het rapport worden weergegeven zijn die van de auteurs en weerspiegelen niet noodzakelijkerwijs de mening van de COGEM. 2 Contents Voorwoord/Preface …………………5 Chapter 1 Worldwide cultural differences in socio-ethical views in relation to biotechnology: Overview and summary ……………………..7 Chapter 2 Monsters, boundary work and framing: Biotechnology from an anthropological perspective …………………….27 Chapter 3 Hwang Woo Suk and the Korean stem cell debacle: Scientific fraud, techno-nationalism and the ‘Wild East’ ……………………..47 Chapter 4 East Asia and the “GM Cold War”: The international struggle over precaution, labelling and segregation ………….77 3 4 Voorwoord/Preface Het voorliggende rapport Worldwide Cultural Differences in Socio-Ethical Views in Relation to Biotechnology (Mondiale cultuurverschillen in de ethisch maatschappelijke opvattingen i.v.m. biotechnologie) is samengesteld in opdracht van de Commissie Genetische Modificatie (COGEM). Het is mede bedoeld ter voorbereiding van de nieuwe Trendanalyse Biotechnologie die in 2007 zal worden uitgebracht. De onderzoekswerkzaamheden (voornamelijk ‘desk research’) zijn verricht door dr. Henk van den Belt onder directe supervisie van Prof. dr. Jozef Keulartz. De uitvoering van het project is begeleid door een begeleidingscommissie waarin Prof.