Reading Rouhani

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The IRGC in the Age of Ebrahim Raisi: Decision-Making and Factionalism in Iran’S Revolutionary Guard

The IRGC in the Age of Ebrahim Raisi: Decision-Making and Factionalism in Iran’s Revolutionary Guard SAEID GOLKAR AUGUST 2021 KASRA AARABI Contents Executive Summary 4 The Raisi Administration, the IRGC and the Creation of a New Islamic Government 6 The IRGC as the Foundation of Raisi’s Islamic Government The Clergy and the Guard: An Inseparable Bond 16 No Coup in Sight Upholding Clerical Superiority and Preserving Religious Legitimacy The Importance of Understanding the Guard 21 Shortcomings of Existing Approaches to the IRGC A New Model for Understanding the IRGC’s Intra-elite Factionalism 25 The Economic Vertex The Political Vertex The Security-Intelligence Vertex Charting IRGC Commanders’ Positions on the New Model Shades of Islamism: The Ideological Spectrum in the IRGC Conclusion 32 About the Authors 33 Saeid Golkar Kasra Aarabi Endnotes 34 4 The IRGC in the Age of Ebrahim Raisi Executive Summary “The Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps [IRGC] has excelled in every field it has entered both internationally and domestically, including security, defence, service provision and construction,” declared Ayatollah Ebrahim Raisi, then chief justice of Iran, in a speech to IRGC commanders on 17 March 2021.1 Four months on, Raisi, who assumes Iran’s presidency on 5 August after the country’s June 2021 election, has set his eyes on further empowering the IRGC with key ministerial and bureaucratic positions likely to be awarded to guardsmen under his new government. There is a clear reason for this ambition. Expanding the power of the IRGC serves the interests of both Raisi and his 82-year-old mentor, Ayatollah Ali Khamenei, the supreme leader of the Islamic Republic. -

IRAN EXECUTIVE SUMMARY the Islamic Republic of Iran

IRAN EXECUTIVE SUMMARY The Islamic Republic of Iran is a constitutional, theocratic republic in which Shia Muslim clergy and political leaders vetted by the clergy dominate the key power structures. Government legitimacy is based on the twin pillars of popular sovereignty--albeit restricted--and the rule of the supreme leader of the Islamic Revolution. The current supreme leader, Ayatollah Ali Khamenei, was chosen by a directly elected body of religious leaders, the Assembly of Experts, in 1989. Khamenei’s writ dominates the legislative, executive, and judicial branches of government. He directly controls the armed forces and indirectly controls internal security forces, the judiciary, and other key institutions. The legislative branch is the popularly elected 290-seat Islamic Consultative Assembly, or Majlis. The unelected 12-member Guardian Council reviews all legislation the Majlis passes to ensure adherence to Islamic and constitutional principles; it also screens presidential and Majlis candidates for eligibility. Mahmoud Ahmadinejad was reelected president in June 2009 in a multiparty election that was generally considered neither free nor fair. There were numerous instances in which elements of the security forces acted independently of civilian control. Demonstrations by opposition groups, university students, and others increased during the first few months of the year, inspired in part by events of the Arab Spring. In February hundreds of protesters throughout the country staged rallies to show solidarity with protesters in Tunisia and Egypt. The government responded harshly to protesters and critics, arresting, torturing, and prosecuting them for their dissent. As part of its crackdown, the government increased its oppression of media and the arts, arresting and imprisoning dozens of journalists, bloggers, poets, actors, filmmakers, and artists throughout the year. -

IRAN COUNTRY of ORIGIN INFORMATION (COI) REPORT COI Service

IRAN COUNTRY OF ORIGIN INFORMATION (COI) REPORT COI Service Date 28 June 2011 IRAN JUNE 2011 Contents Preface Latest News EVENTS IN IRAN FROM 14 MAY TO 21 JUNE Useful news sources for further information REPORTS ON IRAN PUBLISHED OR ACCESSED BETWEEN 14 MAY AND 21 JUNE Paragraphs Background Information 1. GEOGRAPHY ............................................................................................................ 1.01 Maps ...................................................................................................................... 1.04 Iran ..................................................................................................................... 1.04 Tehran ................................................................................................................ 1.05 Calendar ................................................................................................................ 1.06 Public holidays ................................................................................................... 1.07 2. ECONOMY ................................................................................................................ 2.01 3. HISTORY .................................................................................................................. 3.01 Pre 1979: Rule of the Shah .................................................................................. 3.01 From 1979 to 1999: Islamic Revolution to first local government elections ... 3.04 From 2000 to 2008: Parliamentary elections -

Iran: Ethnic and Religious Minorities

Order Code RL34021 Iran: Ethnic and Religious Minorities Updated November 25, 2008 Hussein D. Hassan Information Research Specialist Knowledge Services Group Iran: Ethnic and Religious Minorities Summary Iran is home to approximately 70.5 million people who are ethnically, religiously, and linguistically diverse. The central authority is dominated by Persians who constitute 51% of Iran’s population. Iranians speak diverse Indo-Iranian, Semitic, Armenian, and Turkic languages. The state religion is Shia, Islam. After installation by Ayatollah Khomeini of an Islamic regime in February 1979, treatment of ethnic and religious minorities grew worse. By summer of 1979, initial violent conflicts erupted between the central authority and members of several tribal, regional, and ethnic minority groups. This initial conflict dashed the hope and expectation of these minorities who were hoping for greater cultural autonomy under the newly created Islamic State. The U.S. State Department’s 2008 Annual Report on International Religious Freedom, released September 19, 2008, cited Iran for widespread serious abuses, including unjust executions, politically motivated abductions by security forces, torture, arbitrary arrest and detention, and arrests of women’s rights activists. According to the State Department’s 2007 Country Report on Human Rights (released on March 11, 2008), Iran’s poor human rights record worsened, and it continued to commit numerous, serious abuses. The government placed severe restrictions on freedom of religion. The report also cited violence and legal and societal discrimination against women, ethnic and religious minorities. Incitement to anti-Semitism also remained a problem. Members of the country’s non-Muslim religious minorities, particularly Baha’is, reported imprisonment, harassment, and intimidation based on their religious beliefs. -

Reimagine a F G H a N I S T a N

REIMAGINE A F G H A N I S T A N A N I N I T I A T I V E B Y R A I S I N A H O U S E REIMAGINE A F G H A N I S T A N INTRODUCTION . Afghanistan equals Culture, heritage, music, poet, spirituality, food & so much more. The country had witnessed continuous violence for more than 4 ................................................... decades & this has in turn overshadowed the rich cultural heritage possessed by the country, which has evolved through mellinnias of Cultural interaction & evolution. Reimagine Afghanistan as a digital magazine is an attempt by Raisina House to explore & portray that hidden side of Afghanistan, one that is almost always overlooked by the mainstream media, the side that is Humane. Afghanistan is rich in Cultural Heritage that has seen mellinnias of construction & destruction but has managed to evolve to the better through the ages. Issued as part of our vision project "Rejuvenate Afghanistan", the magazine is an attempt to change the existing perception of Afghanistan as a Country & a society bringing forward that there is more to the Country than meets the eye. So do join us in this journey to explore the People, lifestyle, Art, Food, Music of this Adventure called Afghanistan. C O N T E N T S P A G E 1 AFGHANISTAN COUNTRY PROFILE P A G E 2 - 4 PEOPLE ETHNICITY & LANGUAGE OF AFGHANISTAN P A G E 5 - 7 ART OF AFGHANISTAN P A G E 8 ARTISTS OF AFGHANISTAN P A G E 9 WOOD CARVING IN AFGHANISTAN P A G E 1 0 GLASS BLOWING IN AFGHANISTAN P A G E 1 1 CARPETS OF AFGHANISTAN P A G E 1 2 CERAMIC WARE OF AFGHANISTAN P A G E 1 3 - 1 4 FAMOUS RECIPES OF AFGHANISTAN P A G E 1 5 AFGHANI POETRY P A G E 1 6 ARCHITECTURE OF AFGHANISTAN P A G E 1 7 REIMAGINING AFGHANISTAN THROUGH CINEMA P A G E 1 8 AFGHANI MOVIE RECOMMENDATION A B O U T A F G H A N I S T A N Afghanistan Country Profile: The Islamic Republic of Afghanistan is a landlocked country situated between the crossroads of Western, Central, and Southern Asia and is at the heart of the continent. -

Gandhi's View on Judaism and Zionism in Light of an Interreligious

religions Article Gandhi’s View on Judaism and Zionism in Light of an Interreligious Theology Ephraim Meir 1,2 1 Department of Jewish Philosophy, Bar-Ilan University, Ramat Gan 5290002, Israel; [email protected] 2 Stellenbosch Institute for Advanced Study (STIAS), Wallenberg Research Centre at Stellenbosch University, Stellenbosch 7600, South Africa Abstract: This article describes Gandhi’s view on Judaism and Zionism and places it in the framework of an interreligious theology. In such a theology, the notion of “trans-difference” appreciates the differences between cultures and religions with the aim of building bridges between them. It is argued that Gandhi’s understanding of Judaism was limited, mainly because he looked at Judaism through Christian lenses. He reduced Judaism to a religion without considering its peoplehood dimension. This reduction, together with his political endeavors in favor of the Hindu–Muslim unity and with his advice of satyagraha to the Jews in the 1930s determined his view on Zionism. Notwithstanding Gandhi’s problematic views on Judaism and Zionism, his satyagraha opens a wide-open window to possibilities and challenges in the Near East. In the spirit of an interreligious theology, bridges are built between Gandhi’s satyagraha and Jewish transformational dialogical thinking. Keywords: Gandhi; interreligious theology; Judaism; Zionism; satyagraha satyagraha This article situates Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi’s in the perspective of a Jewish dialogical philosophy and theology. I focus upon the question to what extent Citation: Meir, Ephraim. 2021. Gandhi’s religious outlook and satyagraha, initiated during his period in South Africa, con- Gandhi’s View on Judaism and tribute to intercultural and interreligious understanding and communication. -

M6.3 - 89Km SE of Bandar Bushehr, Iran 2013-04-09 11:52:50 UTC

Earthquake Hazards Program M6.3 - 89km SE of Bandar Bushehr, Iran 2013-04-09 11:52:50 UTC PAGER - ORANGE ShakeMap - VIII DYFI? - V Google Earth KML Summary Location and Magnitude contributed by: USGS, NEIC, Golden, Colorado (and predecessors) + - Iran 50 km 28.500°N, 51.591°E 30 mi Depth: 10.0km (6.2mi) Powered by Leaflet Event Time 2013-04-09 11:52:50 UTC 2013-04-09 16:22:50 UTC+04:30 at epicenter 2013-04-09 20:52:50 UTC+09:00 system time Location 28.500°N 51.591°E depth=10.0km (6.2mi) Nearby Cities 89km (55mi) SE of Bandar Bushehr, Iran 92km (57mi) SSE of Borazjan, Iran 103km (64mi) WSW of Firuzabad, Iran 124km (77mi) S of Kazerun, Iran 272km (169mi) NNE of Manama, Bahrain Related Links Additional earthquake information for Iran Earthquake Summary Poster View location in Google Maps Tectonic Summary The April 9, 2013 M6.3 earthquake in southern Iran occurred as result of northeast-southwest oriented thrust-type motion in the shallow crust of the Arabian plate. The depth and style of faulting in this event are consistent with shortening of the shallow Arabian crust within the Zagros Mountains in response to active convergence between the Arabian and Eurasian plates. Because this event is an intraplate event, occurring almost 300 km south of the main plate boundary, and since the event likely did not break the surface, precise identification of the causative fault is difficult at this time. On a broad scale, the seismotectonics of southern Iran are controlled by active convergence between the Arabian and Eurasian tectonic plates. -

Iran and Yemen; Study the Reflection of the Islamic Revolution of Iran on Yemen and Its Results

Iran and Yemen; Study the Reflection of the Islamic Revolution of Iran on Yemen and Its Results Amir Reza Emami¹, Fatemeh Zare² ¹,2 Graduate of Political Science (International Relations), Department of Law and Political Science, Faculty of Social Sciences and Humanities, Yazd, Yazd University, Iran. Abstract The Islamic Revolution of Iran took place in 1789 and was the first successful revolution inspired by Islam. Undoubtedly, this revolution had repercussions on the peripheral and semi-peripheral countries of Iran, and among the semi-peripheral countries of Iran, which was affected by the Iranian revolution, was Yemen. In the following years, with the beginning of the Arab Spring (Islamic Awakening), this country underwent changes and protest movements were formed in it, the content of which was very close to the foundations of the Islamic Revolution of Iran in 1789. These protests and anti-government movements in Yemen at the time led to the revolution and ultimately to the victory of the Yemeni Houthis and the Ansarullah movement. But what could be the consequences of this event in Yemen? Do these results include the system of the Islamic Republic of Iran? In fact, the main question of this research is what are the results of the reflection of the Islamic Revolution of Iran on Yemen. Therefore, this study seeks to first examine the reflection of the Islamic Revolution in Yemen and then explain its results. The method of the present research is qualitative and based on descriptive-analytical and the method of collecting data and information is based on documentary studies, libraries and reputable research and extension science journals and various statistics. -

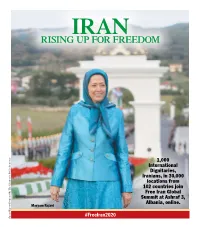

Rising up for Freedom

IRAN RISING UP FOR FREEDOM 1,000 International Dignitaries, Iranians, in 30,000 locations from 102 countries join Free Iran Global Summit at Ashraf 3, Albania, online. Maryam Rajavi #FreeIran2020 Special Report Sponsored The by Alliance Public for Awareness Iranian dissidents rally for regime change in Tehran BY BEN WOLFGANG oppressive government that has ruled Iran from both political parties participating has proven it can’t deliver for its people. tHe WasHInGtOn tImes since the Islamic Revolution of 1979. Leaders represented a who’s who list of American “The Iranian people want change, to of the NCRI, which is comprised of multiple “formers,” including former Sen. Joseph I. have democracy, finally to have human Iran’s theocracy is at the weakest point other organizations, say the council has seen Lieberman of Connecticut, former Penn- rights, to finally have economic wealth, of its four-decade history and facing un- its stature grow to the point that Iranian sylvania Gov. Tom Ridge, former Attorney no more hunger. The will of the people precedented challenges from a courageous officials can no longer deny its influence. General Michael Mukasey, retired Marine is much stronger than any oppressive citizenry hungry for freedom, Iranian dis- The NCRI has many American support- Commandant James T. Conway and others. measure of an Iranian regime,” said Martin sidents and prominent U.S. and European ers, including some with close relationships Several current U.S. officials also delivered Patzelt, a member of German Parliament. politicians said Friday at a major interna- to Mr. Trump, such as former New York remarks, including Sen. -

Tightening the Reins How Khamenei Makes Decisions

MEHDI KHALAJI TIGHTENING THE REINS HOW KHAMENEI MAKES DECISIONS MEHDI KHALAJI TIGHTENING THE REINS HOW KHAMENEI MAKES DECISIONS POLICY FOCUS 126 THE WASHINGTON INSTITUTE FOR NEAR EAST POLICY www.washingtoninstitute.org Policy Focus 126 | March 2014 The opinions expressed in this Policy Focus are those of the author and not necessarily those of The Washington Institute for Near East Policy, its Board of Trustees, or its Board of Advisors. All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including pho- tocopy, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. © 2014 by The Washington Institute for Near East Policy The Washington Institute for Near East Policy 1828 L Street NW, Suite 1050 Washington, DC 20036 Cover: Iran’s Supreme Leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei holds a weapon as he speaks at the University of Tehran. (Reuters/Raheb Homavandi). Design: 1000 Colors CONTENTS Executive Summary | V 1. Introduction | 1 2. Life and Thought of the Leader | 7 3. Khamenei’s Values | 15 4. Khamenei’s Advisors | 20 5. Khamenei vs the Clergy | 27 6. Khamenei vs the President | 34 7. Khamenei vs Political Institutions | 44 8. Khamenei’s Relationship with the IRGC | 52 9. Conclusion | 61 Appendix: Profile of Hassan Rouhani | 65 About the Author | 72 1 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY EVEN UNDER ITS MOST DESPOTIC REGIMES , modern Iran has long been governed with some degree of consensus among elite factions. Leaders have conceded to or co-opted rivals when necessary to maintain their grip on power, and the current regime is no excep- tion. -

Bushehr: Land of Sun and Sea Haley Asks for Cooperate with Riyadh Bushehr Province Is One of the 31 Provinces of Decertifying Iran’S Iran

Tomorrow is ours Today’s Weather Call to prayer time in Isfahan Isfahan Tehran Morning call to prayer : ° ° 05:19:38 24 c 37 c Noon call to prayer : 13:01:16 Ahvaz Evening call to prayer: ° 19:38:02 28 c ° 45 c Qibla Direction Qazvin 17 ° c 37 ° c 18 ° c 34 ° c NasPro-environment e NewspaperFarda Thursday|7September 2017 |No.5491 naslfarda naslefardanews 30007232 WWW.NASLEFARDA.NET Page:23 In The News Tehran Ready to Bushehr: Land of Sun and Sea Haley asks for Cooperate with Riyadh Bushehr province is one of the 31 provinces of decertifying Iran’s Iran. It is in the south of the country, with a long compliance with to Resolve Muslims’ coastline alongside the Persian Gulf. Problems: Zarif With a provincial capital by the same name, JCPOA ranian Foreign Minister Bushehr has nine cities: Bushehr, Dashtestan, Implying the nature of the IMohammad Javad Zarif said the Dashti, Dayyer, Deylam, Jam, Kangan, Genaveh, US administration’s political country is ready to work with all and Tangestan. approach toward nuclear deal Islamic countries, including Saudi Geographically, the province is divided it into with Iran, US Ambassador to Arabia, to help resolve Muslims’ two regions: the plains in the west and southwest, the UN Nikki Haley laid out problems in the Middle East region and the mountainous region in the north and a case for President Donald and the world.“We are ready to northeast. The weather in the former is very warm Trump to step back from the cooperate with Islamic countries and humid, while the latter has a dry and warm Iran nuclear deal. -

Ethics & Critical Thinking in Conservation

his collection of essays brings to focus a moment in the evolution of the & Critical Thinking Ethics Tcomplex decision making processes required when conservators consider the Ethics & treatment of cultural heritage materials. The papers presented here are drawn from two consecutive years of presentations at the American Institute for Conservation of Historic and Artistic Works (AIC) Annual Meeting General Sessions. These Critical were, in 2010, The Conservation Continuum: Examining the Past, Envisioning the Future, and in 2011, Ethos Logos Pathos: Ethical Principles and Critical Thinking in Conservation. Contributors to this thoughtful book include Barbara Appelbaum, Thinking Deborah Bede, Gabriëlle Beentjes, James Janowski, Jane E. Klinger, Frank Matero, Salvador Muñoz Viñas, Bill Wei, and George Wheeler. in Conservation in Conservationin A publication of the American Institute for Conservation of Historic & Artistic Works Edited by Pamela Hatchfield Ethics & Critical Thinking in Conservation Edited by Pamela Hatchfield American Institute for Conservation of Historic & Artistic Works The American Institute for Conservation of Historic & Artistic Works (AIC) promotes the preservation of cultural heritage as a means toward a deeper understanding of our shared humanity—the need to express ourselves through creative achievement in the arts, literature, architecture, and technology. We honor the history and integrity of achievements in the humanities and science through the preservation of cultural materials for future generations. American