DĀNESH: the OU Undergraduate Journal of Iranian Studies

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Beginners Guides to the Religions and Beliefs Islam

Beginners guides to the religions and beliefs Islam Teachers need subject knowledge to teach RE well. There is no substitute for this, and it is part of our professional responsibility. Any RE subject leader might use this set of support materials to help class teachers who are not expert in a religion they are going to teach. The guides to each religion here are very brief – just four or five pages usually, and carefully focused on what a teacher need to be reminded about. They are in danger of being trite or superficial, but perhaps are better than nothing. There is on every religion a wide introductory literature, and all teachers of RE will do their work better if they improve their knowledge by wider reading than is offered here. But perhaps it is worth giving these starting points to busy teachers. Note that no primary teacher needs to know about 6 religions – if you teach one year group, then two or three religions will be part of the syllabus for that year. In general terms, the following guidance points apply to teaching about any religion: 1. Respect. Speak with respect about the faith: any religion with tens of millions of followers is being studied because the people within the faith deserve our respect. 2. Diversity. Talk about ‘some / many /most’ believers, but not about ‘All believers’. Diversity is part of every religion. 3. Neutrality. Leave ‘insider language’ to insiders. A Sikh visitor can say ‘We believe...’ but teachers will do best to say ‘Many Sikhs believe’ or ‘many Christians believe...’ 4. -

Hadith and Its Principles in the Early Days of Islam

HADITH AND ITS PRINCIPLES IN THE EARLY DAYS OF ISLAM A CRITICAL STUDY OF A WESTERN APPROACH FATHIDDIN BEYANOUNI DEPARTMENT OF ARABIC AND ISLAMIC STUDIES UNIVERSITY OF GLASGOW Thesis submitted for the degree of Ph.D. in the Faculty of Arts at the University of Glasgow 1994. © Fathiddin Beyanouni, 1994. ProQuest Number: 11007846 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a com plete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. uest ProQuest 11007846 Published by ProQuest LLC(2018). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States C ode Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. ProQuest LLC. 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106- 1346 M t&e name of &Jla&, Most ©racious, Most iKlercifuI “go take to&at tfje iHessenaer aikes you, an& refrain from to&at tie pro&tfuts you. &nO fear gJtati: for aft is strict in ftunis&ment”. ©Ut. It*. 7. CONTENTS Acknowledgements ......................................................................................................4 Abbreviations................................................................................................................ 5 Key to transliteration....................................................................6 A bstract............................................................................................................................7 -

Rituals and Sacraments

Rituals and Sacraments Rituals, Sacraments (Christian View) By Dr. Thomas Fisch Christians, like their Islamic brothers and sisters, pray to God regularly. Much like Islam, the most important Christian prayer is praise and thanksgiving given to God. Christians pray morning and evening, either alone or with others, and at meals. But among the most important Christian prayers are the community ritual celebrations known as "The Sacraments" [from Latin, meaning "signs"]. Christians also celebrate seasons and festival days [see Feasts and Seasons]. Christians believe that Jesus of Nazareth, who taught throughout Galilee and Judea and who died on a cross, was raised from the dead by God in order to reveal the full extent of God's love for all human beings. Jesus reveals God's saving love through the Christian Scriptures (the New Testament) and through the community of those who believe in him, "the Church," whose lives and whose love for their fellow human beings are meant to be witnesses and signs of the fullness of God's love. Within the community of the Christian Church these important ritual celebrations of worship, the sacraments, take place. Their purpose is to build up the Christian community, and each individual Christian within it, in a way that will make the Church as a whole and all Christians more and more powerful and effective witnesses and heralds of God's love for all people and of God's desire to give everlasting life to all human beings. Each of the sacraments is fundamentally an action of worship and prayer. Ideally, each is celebrated in a community ritual prayer-action in which everyone present participates in worshipping God. -

The IRGC in the Age of Ebrahim Raisi: Decision-Making and Factionalism in Iran’S Revolutionary Guard

The IRGC in the Age of Ebrahim Raisi: Decision-Making and Factionalism in Iran’s Revolutionary Guard SAEID GOLKAR AUGUST 2021 KASRA AARABI Contents Executive Summary 4 The Raisi Administration, the IRGC and the Creation of a New Islamic Government 6 The IRGC as the Foundation of Raisi’s Islamic Government The Clergy and the Guard: An Inseparable Bond 16 No Coup in Sight Upholding Clerical Superiority and Preserving Religious Legitimacy The Importance of Understanding the Guard 21 Shortcomings of Existing Approaches to the IRGC A New Model for Understanding the IRGC’s Intra-elite Factionalism 25 The Economic Vertex The Political Vertex The Security-Intelligence Vertex Charting IRGC Commanders’ Positions on the New Model Shades of Islamism: The Ideological Spectrum in the IRGC Conclusion 32 About the Authors 33 Saeid Golkar Kasra Aarabi Endnotes 34 4 The IRGC in the Age of Ebrahim Raisi Executive Summary “The Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps [IRGC] has excelled in every field it has entered both internationally and domestically, including security, defence, service provision and construction,” declared Ayatollah Ebrahim Raisi, then chief justice of Iran, in a speech to IRGC commanders on 17 March 2021.1 Four months on, Raisi, who assumes Iran’s presidency on 5 August after the country’s June 2021 election, has set his eyes on further empowering the IRGC with key ministerial and bureaucratic positions likely to be awarded to guardsmen under his new government. There is a clear reason for this ambition. Expanding the power of the IRGC serves the interests of both Raisi and his 82-year-old mentor, Ayatollah Ali Khamenei, the supreme leader of the Islamic Republic. -

Zoroastrian Ethics by MA Buch

The Gnekwad Stu<Uc'^ in Rdi/tuii and Plcilu-^oph i/ : /I ZOKOASTRIAN ETHICS IVintod at the Mirfsion Press, Siirat l.y n. K. 8colt, and imblislieil l»y A. G. Wi(l;.'ery the Collej,'e, Baroda. I. V. 1919. ZOROASTHIAN ETHICS By MAGAXLAL A. BUCH, M. A. Fellow of the Seminar for the Comparative Stn<ly of IJelifjioiiP, Barotla, With an Infrnrhicfion hv ALBAN n. WrDGERY, ^f. A. Professor of Philosophy and of the Comparative Study of PiPlii^doiis, Baroda. B A K D A 515604 P n E F A C E The present small volume was undertaken as one subject of study as Fellow in the Seminar for the Comparative Study of Religions established in the College, Baroda, by His Highness the Maharaja Sayaji Eao Gaekwad, K C. S. I. etc. The subject was suggested by Professor Widgery who also guided the author in the plan and in the general working out of the theme. It is his hope that companion volumes on the ethical ideas associated with other religions will shortly be undertaken. Such ethical studies form an important part of the aim which His Highness had in view in establishing the Seminar. The chapter which treats of the religious conceptions is less elaborate than it might well have been, because Dr. Dhalla's masterly volume on Zomasfrirm Theolof/y^ New York, 1914, cannot be dispens- ed with by any genuine student of Zoroastrian- ism, and all important details may be learned from it. It only remains to thank I'rotessor Widgcrv lor writinf,' a L;enoral introduotion and for his continued help thronghont tho process of the work. -

On the Good Faith

On the Good Faith Zoroastrianism is ascribed to the teachings of the legendary prophet Zarathustra and originated in ancient times. It was developed within the area populated by the Iranian peoples, and following the Arab conquest, it formed into a diaspora. In modern Russia it has evolved since the end of the Soviet era. It has become an attractive object of cultural produc- tion due to its association with Oriental philosophies and religions and its rearticulation since the modern era in Europe. The lasting appeal of Zoroastrianism evidenced by centuries of book pub- lishing in Russia was enlivened in the 1990s. A new, religious, and even occult dimension was introduced with the appearance of neo-Zoroastrian groups with their own publications and online websites (dedicated to Zoroastrianism). This study focuses on the intersectional relationships and topical analysis of different Zoroastrian themes in modern Russia. On the Good Faith A Fourfold Discursive Construction of Zoroastrianism in Contemporary Russia Anna Tessmann Anna Tessmann Södertörns högskola SE-141 89 Huddinge [email protected] www.sh.se/publications On the Good Faith A Fourfold Discursive Construction of Zoroastrianism in Contemporary Russia Anna Tessmann Södertörns högskola 2012 Södertörns högskola SE-141 89 Huddinge www.sh.se/publications Cover Image: Anna Tessmann Cover Design: Jonathan Robson Layout: Jonathan Robson & Per Lindblom Printed by E-print, Stockholm 2012 Södertörn Doctoral Dissertations 68 ISSN 1652-7399 ISBN 978-91-86069-50-6 Avhandlingar utgivna vid -

ZOROASTRIANISM Chapter Outline and Unit Summaries I. Introduction

CHAPTER TEN: ZOROASTRIANISM Chapter Outline and Unit Summaries I. Introduction A. Zoroastrianism: One of the World’s Oldest Living Religions B. Possesses Only 250,000 Adherents, Most Living in India C. Zoroastrianism Important because of Influence of Zoroastrianism on Christianity, Islam, Middle Eastern History, and Western Philosophy II. Pre-Zoroastrian Persian Religion A. The Gathas: Hymns of Early Zoroastrianism Provide Clues to Pre- Zoroastrian Persian Religion 1. The Gathas Considered the words of Zoroaster, and are Foundation for all Later Zoroastrian Scriptures 2. The Gathas Disparage Earlier Persian Religions B. The Aryans (Noble Ones): Nomadic Inhabitants of Ancient Persia 1. The Gathas Indicate Aryans Nature Worshippers Venerating Series of Deities (also mentioned in Hindu Vedic literature) a. The Daevas: Gods of Sun, Moon, Earth, Fire, Water b. Higher Gods, Intar the God of War, Asha the God of Truth and Justice, Uruwana a Sky God c. Most Popular God: Mithra, Giver and Benefactor of Cattle, God of Light, Loyalty, Obedience d. Mithra Survives in Zoroastrianism as Judge on Judgment Day 2. Aryans Worship a Supreme High God: Ahura Mazda (The Wise Lord) 3. Aryan Prophets / Reformers: Saoshyants 97 III. The Life of Zoroaster A. Scant Sources of Information about Zoroaster 1. The Gathas Provide Some Clues 2. Greek and Roman Writers (Plato, Pliny, Plutarch) Comment B. Zoroaster (born between 1400 and 1000 B.C.E.) 1. Original Name (Zarathustra Spitama) Indicates Birth into Warrior Clan Connected to Royal Family of Ancient Persia 2. Zoroaster Becomes Priest in His Religion; the Only Founder of a World Religion to be Trained as a Priest 3. -

Harvard Theological Review Zoroastrianism and Judaism

Harvard Theological Review http://journals.cambridge.org/HTR Additional services for Harvard Theological Review: Email alerts: Click here Subscriptions: Click here Commercial reprints: Click here Terms of use : Click here Zoroastrianism and Judaism. George William Carter, Ph.D. The Gorham Press. 1918. Pp. 116. \$2.00. Louis Ginzberg Harvard Theological Review / Volume 13 / Issue 01 / January 1920, pp 89 - 92 DOI: 10.1017/S0017816000012888, Published online: 03 November 2011 Link to this article: http://journals.cambridge.org/ abstract_S0017816000012888 How to cite this article: Louis Ginzberg (1920). Harvard Theological Review, 13, pp 89-92 doi:10.1017/S0017816000012888 Request Permissions : Click here Downloaded from http://journals.cambridge.org/HTR, IP address: 130.60.206.74 on 05 May 2015 BOOK REVIEWS 89 with the same general period and locality. The Habiru are clearly Aramaean nomads who press continually westward, until in the reign of Ahnaton they occupy the whole of Palestine, from the Phoe- nician cities in the north to the district around Jerusalem. All this is in striking harmony with the movements of Hebrew tribes as re- flected in the patriarchal traditions (pp. 82 ff.). That the main body of the Israelites had no part in the migration to Egypt is borne out by the mention of 'Asaru (the district assigned to the tribe of Asher) among the conquests of Sety I (c. 1313 B.C.), and the inclu- sion of Israel in the list of peoples subdued by Mineptah (c. 1222 B.C.). It is possible indeed that Israelite families may have participated in the southward movement of Amurru peoples under the Hyksos domi- nation of Egypt, but the migration proper was confined to Joseph tribes, probably during the flourishing period of the Empire (from the reign of Thutmosi III onwards). -

Football in Iran. National Pride and Regional Claims Christian Bromberger

Football in Iran. National pride and regional claims Christian Bromberger To cite this version: Christian Bromberger. Football in Iran. National pride and regional claims. Soutenir l’équipe na- tionale de football. Enjeux politiques et identitaires , 2016, 978-2-8004-1603-8. hal-01422072 HAL Id: hal-01422072 https://hal-amu.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-01422072 Submitted on 23 Dec 2016 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Christian Bromberger Le football en Iran. Sentiment national et revendications identitaires Le sentiment national est fortement ancré en Iran. On ne peut comprendre ce pays si l’on ne tientpascompte de cette ferveur chauvine, de cette fierté nationale qui s’ancre dans la conscience partagée d’une histoire multimillénaire, fierté qui unit tous les Iraniens, quelle que soit leur tendance politique et qu’ils résident en Iran ou qu’ils soient exilés. Au fil du XXème siècle,le vieil empire multiethnique s’est transformé en un État-nation centralisé renforçant et exacerbant le sentiment national, un sentiment que n’ont pas refroidi les velléités internationales de la révolution islamique et qui a été, au contraire,avivé par la longue guerre contre l’Irak (1980-1988). -

Dynamics of Iranian-Saudi Relations in the Persian Gulf Regional Security Complex (1920-1979) Nima Baghdadi Florida International University, [email protected]

Florida International University FIU Digital Commons FIU Electronic Theses and Dissertations University Graduate School 3-22-2018 Dynamics of Iranian-Saudi Relations in the Persian Gulf Regional Security Complex (1920-1979) Nima Baghdadi Florida International University, [email protected] DOI: 10.25148/etd.FIDC006552 Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.fiu.edu/etd Part of the International Relations Commons, and the Other Political Science Commons Recommended Citation Baghdadi, Nima, "Dynamics of Iranian-Saudi Relations in the Persian Gulf Regional Security Complex (1920-1979)" (2018). FIU Electronic Theses and Dissertations. 3652. https://digitalcommons.fiu.edu/etd/3652 This work is brought to you for free and open access by the University Graduate School at FIU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in FIU Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of FIU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. FLORIDA INTERNATIONAL UNIVERSITY Miami, Florida DYNAMICS OF IRANIAN-SAU DI RELATIONS IN THE P ERSIAN GULF REGIONAL SECURITY COMPLEX (1920-1979) A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in POLITICAL SCIENCE by Nima Baghdadi 2018 To: Dean John F. Stack Steven J. Green School of International Relations and Public Affairs This dissertation, written by Nima Baghdadi, and entitled Dynamics of Iranian-Saudi Relations in the Persian Gulf Regional Security Complex (1920-1979), having been approved in respect to style and intellectual content, is referred to you for judgment. We have read this dissertation and recommend that it be approved. __________________________________ Ralph S. Clem __________________________________ Harry D. -

REIMAGINING INTERFAITH Shayda Sales

With Best Compliments From The Incorportated Trustees Of the Zoroastrian Charity Funds of Hong Kong, Canton & Macao FEZANAJOURNAL www.fezana.org Vol 32 No 3 Fall / Paiz 1387 AY 3756 Z PUBLICATION OF THE FEDERATION OF ZOROASTRIAN ASSOCIATIONS OF NORTH AMERICA - CONTENT- Editor in Chief Dolly Dastoor, editor(@)fezana.org Graphic & Layout Shahrokh Khanizadeh, www.khanizadeh.info 02 Editorial Dolly Dastoor Technical Assistant Coomie Gazdar Consultant Editor Lylah M. Alphonse, lmalphonse(@)gmail.com 03 Message from the Language Editor Douglas Lange, Deenaz Coachbuilder President Cover Design Feroza Fitch, ffitch(@)lexicongraphics.com 04 FEZANA update Publications Chair Behram Pastakia, bpastakia(@)aol.com Marketing Manager Nawaz Merchant, [email protected] Columnists Shazneen Rabadi Gandhi, rabadis(@)gmail.com Teenaz Javat, teenazjavat(@)hotmail.com Page 7 MahrukhMotafram, mahrukhm83(@)gmail.com Copy Editors Vahishta Canteenwalla Yasmin Pavri Nazneen Khumbatta Subscription Managers Arnavaz Sethna, ahsethna(@)yahoo.com Kershaw Khumbatta, Arnavaz Sethna(@)yahoo.com Mehr- Avan – Adar 1387 AY (Fasli) Ardebehesht – Khordad – Tir 1388 AY (Shenhai) Khordad - Tir – Amordad 1388 AY (Kadimi) Mehrdad Aidun. The ceramic stamped ossuary (a depository of the bones of a deceased) with a removable lid, from the 6 - 7th centuries CE, was discovered in Yumalaktepa, near Shahr-i 11 Archeological Findings Sabz, Uzbekistan, in 2012. In the lower right section of the scene, a priest wearing a padam is shown solemnizing a ritual, while holding in 22 Gatha Study Circle his left hand two narrow, long sticks, identified as barsom. The right half of the scene depicts the heavenly judgment at the Chinwad Bridge. 29 In the News The figure holding scales is Rashne, who weighs the good and evil deeds of the deceased, who is shown as a young boy. -

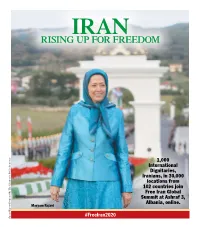

Rising up for Freedom

IRAN RISING UP FOR FREEDOM 1,000 International Dignitaries, Iranians, in 30,000 locations from 102 countries join Free Iran Global Summit at Ashraf 3, Albania, online. Maryam Rajavi #FreeIran2020 Special Report Sponsored The by Alliance Public for Awareness Iranian dissidents rally for regime change in Tehran BY BEN WOLFGANG oppressive government that has ruled Iran from both political parties participating has proven it can’t deliver for its people. tHe WasHInGtOn tImes since the Islamic Revolution of 1979. Leaders represented a who’s who list of American “The Iranian people want change, to of the NCRI, which is comprised of multiple “formers,” including former Sen. Joseph I. have democracy, finally to have human Iran’s theocracy is at the weakest point other organizations, say the council has seen Lieberman of Connecticut, former Penn- rights, to finally have economic wealth, of its four-decade history and facing un- its stature grow to the point that Iranian sylvania Gov. Tom Ridge, former Attorney no more hunger. The will of the people precedented challenges from a courageous officials can no longer deny its influence. General Michael Mukasey, retired Marine is much stronger than any oppressive citizenry hungry for freedom, Iranian dis- The NCRI has many American support- Commandant James T. Conway and others. measure of an Iranian regime,” said Martin sidents and prominent U.S. and European ers, including some with close relationships Several current U.S. officials also delivered Patzelt, a member of German Parliament. politicians said Friday at a major interna- to Mr. Trump, such as former New York remarks, including Sen.