Lesson Plan Chien-Shiung Wu, Chinese Nuclear Physicist

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Tonatory Patterns in Taizhou Wu Tones

TONATORY PATTERNS IN TAIZHOU WU TONES Phil Rose Emeritus Faculty, Australian National University [email protected] ABSTRACT 台州 subgroup of Wu to which Huángyán belongs. The issue has significance within descriptive Recordings of speakers of the Táizhou subgroup of tonetics, tonatory typology and historical linguistics. Wu Chinese are used to acoustically document an Wu dialects – at least the conservative varieties – interaction between tone and phonation first attested show a wide range of tonatory behaviour [11]. One in 1928. One or two of their typically seven or eight finds breathy or ventricular phonation in groups of tones are shown to have what sounds like a mid- tones characterising natural tonal classes of Rhyme glottal-stop, thus demonstrating a new importance for phonotactics and Wu’s complex tone pattern in Wu tonatory typology. Possibly reflecting sandhi. One also finds a single tone characterised by gradual loss, larygealisation appears restricted to the a different non-modal phonation type [12]; or even north and north-west, and is absent in Huángyán two different non-modal phonation types in two dialect where it was first described. A perturbatory tones. However, the Huangyan-type tonation seems model of the larygealisation is tested in an to involve a new variation, with the same phonation experiment determining how much of the complete type in two different tones from the same historical tonal F0 contour can be restored from a few tonal category, thus prompting speculation that it centiseconds of modal F0 at Rhyme onset and offset. developed before the tonal split. The results are used both to acoustically quantify laryngealised tonal F0, with its problematic jitter and 2. -

Official Colours of Chinese Regimes: a Panchronic Philological Study with Historical Accounts of China

TRAMES, 2012, 16(66/61), 3, 237–285 OFFICIAL COLOURS OF CHINESE REGIMES: A PANCHRONIC PHILOLOGICAL STUDY WITH HISTORICAL ACCOUNTS OF CHINA Jingyi Gao Institute of the Estonian Language, University of Tartu, and Tallinn University Abstract. The paper reports a panchronic philological study on the official colours of Chinese regimes. The historical accounts of the Chinese regimes are introduced. The official colours are summarised with philological references of archaic texts. Remarkably, it has been suggested that the official colours of the most ancient regimes should be the three primitive colours: (1) white-yellow, (2) black-grue yellow, and (3) red-yellow, instead of the simple colours. There were inconsistent historical records on the official colours of the most ancient regimes because the composite colour categories had been split. It has solved the historical problem with the linguistic theory of composite colour categories. Besides, it is concluded how the official colours were determined: At first, the official colour might be naturally determined according to the substance of the ruling population. There might be three groups of people in the Far East. (1) The developed hunter gatherers with livestock preferred the white-yellow colour of milk. (2) The farmers preferred the red-yellow colour of sun and fire. (3) The herders preferred the black-grue-yellow colour of water bodies. Later, after the Han-Chinese consolidation, the official colour could be politically determined according to the main property of the five elements in Sino-metaphysics. The red colour has been predominate in China for many reasons. Keywords: colour symbolism, official colours, national colours, five elements, philology, Chinese history, Chinese language, etymology, basic colour terms DOI: 10.3176/tr.2012.3.03 1. -

Oujiang Wu Tones and Acoustic Reconstruction

OUJIANG WU TONES AND ACOUSTIC RECONSTRUCTION PHIL ROSE Linguistics (Arts), Australian National University 1. Introduction We do not expect tones, as phonological phenomena, to vary without limit, but to show similarities, or so-called tonological universals, across varieties (Maddieson 1978). Nevertheless, when one samples tones from different Asian tone languages, or even different dialects, they often show a great variety of pitch shapes. Zhu and Rose (1998) for example demonstrated no less than 25 different tones in four varieties from different sub-groups within the Wu dialects of east central China. (I use the term tone in this paper in a sense analogous to phone, that is, as a constellation of audibly different properties, with pitch predominating but also including length and phonation type, that constitutes observation data for phonological – usually tonemic – analysis.) In exploring the nature of phonological variation in Language, we naturally concentrate on differences. This paper, on the other hand, makes use of how similar tones can be. It looks at variation in tones at seven localities distributed over a fairly small geographical area where the varieties, which belong to the same dialectal sub-group, have been described as homogeneous. Although this study reveals some interesting synchronic linguistic-tonetic variation, the main reason for undertaking it is not typological, but, as befits a festschrift for Harold Koch, historical. As mentioned, the Wu dialects of Chinese are well-known for their tonal complexity. Not only do they exhibit probably the most complex tone sandhi in the world (Rose 1990), but they also show a bewildering variety in their citation tones. -

Autonomy of Chinese Judges: Dynamics of People’S Courts, the Ccp and the Public in Contemporary Judicial Reform

AUTONOMY OF CHINESE JUDGES: DYNAMICS OF PEOPLE’S COURTS, THE CCP AND THE PUBLIC IN CONTEMPORARY JUDICIAL REFORM by YUE LIU LL.B., Jilin University, 2003 LL.M., Jilin University, 2006 A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE AND POSTDOCTORAL STUDIES (Law) THE UNIVERSITY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA (Vancouver) November 2016 © Yue Liu, 2016 Abstract This dissertation is the outcome of author’s observations and empirical research on judicial reform in China from the 1980s to 2015. Focusing on judicial decision making process of judges in Chinese courts, it attempts to answer the following questions: How do the Chinese Communist Party (CCP), the public, and the internal administrative power—three factors essential to Chinese judges’ judicial decision making process— influence the adjudication of individual cases in various periods of judicial reform? How do the increasingly professionalized judges respond to these institutionalized challenges? Moreover, how do the dynamics generated from the interactions among courts, the CCP, and the public shape the norms and institutional building of judges and courts, and affect judicial reform policies in China? This dissertation adopts historical analysis, documentary analysis, and qualitative analysis to seek answers to these questions. It finds that, first, direct influence of the CCP and the public to the judicial behaviours of individual judges is less evident than indirect influence through the administrative oversight in courts’ internal bureaucracy. Second, the relationships between courts, the CCP, and the public are more dynamic in fragmented China. The norms of Chinese judges’ autonomy and institutional changes in courts are constantly shaped by the expectations and compromise of powers of the CCP, the public, and courts. -

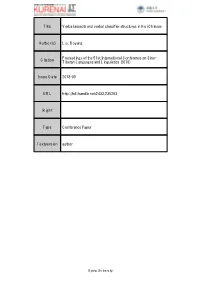

Title Verbal Aspects and Verbal Classifier Structures in Hui Chinese

Title Verbal aspects and verbal classifier structures in Hui Chinese Author(s) Liu, Boyang Proceedings of the 51st International Conference on Sino- Citation Tibetan Languages and Linguistics (2018) Issue Date 2018-09 URL http://hdl.handle.net/2433/235293 Right Type Conference Paper Textversion author Kyoto University Verbal Aspects and Verbal Classifier Structures in Hui Chinese LIU Boyang (EHESS-CRLAO) CONTENT • PART I: Research Purpose • PART II: The definition and classification of VCLs in Sinitic languages – 1. An introduction to Hui Chinese – 2. Previous work on VCLs in Mandarin – 3. A provisional definition and classification of VCLs in Sinitic languages – 4. Lexical aspects indicated by the verb phrase [VERB-VCLP] in Sinitic languages – 5. Relationships between grammatical aspects and the verb phrase [VERB-VCLP- OBJECT] • PART III: Grammatical aspects indicated by special auto-verbal classifier (Auto-VCL) structures in Hui Chinese – 6. The perfective aspect – 7. The imperfective aspect • PART IV: Conclusion PART I: RESEARCH PURPOSE Research Purpose: • Verbal classifiers (VCLs) have been much less studied from a typological perspective than the category of nominal classifiers (NCLs), and even less in the non-Mandarin branches of Sinitic languages, such as the Hui dialects; • In this study, I will introduce relationships between lexical aspects, grammatical aspects and verbal classifier phrases (VCLPs) in Hui Chinese, analyzing the similarities and differences with Standard Mandarin. • Verbal classifier structures in the Hui dialects display a transitional feature compared with Xiang, Gan and Wu, taking auto-verbal classifier (Auto-VCL) structures as examples (auto-VCLs derive from verb reduplicants in the verb phrase [VERB- (‘one’)-VERB]): – Auto-VCLs in the verb phrase [VERB-AUTO VCL] can code the perfective or imperfective aspect in different types of complex sentences in Hui Chinese; – More variety of auto-VCL structures is found in Hui Chinese compared with Xiang and Gan dialects. -

THE MEDIA's INFLUENCE on SUCCESS and FAILURE of DIALECTS: the CASE of CANTONESE and SHAAN'xi DIALECTS Yuhan Mao a Thesis Su

THE MEDIA’S INFLUENCE ON SUCCESS AND FAILURE OF DIALECTS: THE CASE OF CANTONESE AND SHAAN’XI DIALECTS Yuhan Mao A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts (Language and Communication) School of Language and Communication National Institute of Development Administration 2013 ABSTRACT Title of Thesis The Media’s Influence on Success and Failure of Dialects: The Case of Cantonese and Shaan’xi Dialects Author Miss Yuhan Mao Degree Master of Arts in Language and Communication Year 2013 In this thesis the researcher addresses an important set of issues - how language maintenance (LM) between dominant and vernacular varieties of speech (also known as dialects) - are conditioned by increasingly globalized mass media industries. In particular, how the television and film industries (as an outgrowth of the mass media) related to social dialectology help maintain and promote one regional variety of speech over others is examined. These issues and data addressed in the current study have the potential to make a contribution to the current understanding of social dialectology literature - a sub-branch of sociolinguistics - particularly with respect to LM literature. The researcher adopts a multi-method approach (literature review, interviews and observations) to collect and analyze data. The researcher found support to confirm two positive correlations: the correlative relationship between the number of productions of dialectal television series (and films) and the distribution of the dialect in question, as well as the number of dialectal speakers and the maintenance of the dialect under investigation. ACKNOWLEDGMENTS The author would like to express sincere thanks to my advisors and all the people who gave me invaluable suggestions and help. -

A Tonic Dictionary of the Chinese Language in the Canton Dialect Pdf, Epub, Ebook

A TONIC DICTIONARY OF THE CHINESE LANGUAGE IN THE CANTON DIALECT PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Samuel Wells Williams | 868 pages | 01 Aug 2002 | Ganesha Publishing Ltd | 9781862100206 | English, Chinese | Bristol, United Kingdom A Tonic Dictionary of the Chinese Language in the Canton Dialect PDF Book With this information, you can probably understand why it used to be a pet peeve of mine when someone asked me if I was learning Chinese when I was a student. The SensagentBox are offered by sensAgent. Now, I don't know if we can say such words have no Chinese characters per se. In he sailed on the Morrison to Japan. See terms. Item location:. Samuel Wells Williams was a , missionary and from the in the early 19th century. Around , he completed a translation of the Book of Genesis and the Gospel of Matthew into , but the manuscripts were lost in a fire before they could be published. London : Printed by T. Change country: -Select- United States There are 0 items available. Popular Books. Therefore, it will not be discussed in this paper. Download pdf. Are you interested in Mandarin words that aren't written in Hanzi, e. The web service Alexandria is granted from Memodata for the Ebay search. He made two further disc recordings for Linguaphone in and Some characters with multiple pronunciation are commented with meaning, short notes, or usage in each category. Introduction"Sound change, in so far it takes place mechanically, takes place according to laws that admits admit no exceptions. But I think generally those words would either come with a corresponding character, or be fitted to one. -

ISO 639-3 Code Split Request Template

ISO 639-3 Registration Authority Request for Change to ISO 639-3 Language Code Change Request Number: 2019-063 (completed by Registration authority) Date: 2019 Aug 31 Primary Person submitting request: Kirk Miller E-mail address: kirkmiller at gmail dot com Names, affiliations and email addresses of additional supporters of this request: PLEASE NOTE: This completed form will become part of the public record of this change request and the history of the ISO 639-3 code set and will be posted on the ISO 639-3 website. Types of change requests Type of change proposed (check one): 1. Modify reference information for an existing language code element 2. Propose a new macrolanguage or modify a macrolanguage group 3. Retire a language code element from use (duplicate or non-existent) 4. Expand the denotation of a code element through the merging one or more language code elements into it (retiring the latter group of code elements) 5. Split a language code element into two or more new code elements 6. Create a code element for a previously unidentified language For proposing a change to an existing code element, please identify: Affected ISO 639-3 identifier: wuu Associated reference name: Wu Chinese 5. Split a language code element into two or more code elements (a) List the languages into which this code element should be split: Taihu Wu Chinese Taizhou Wu Chinese Wuzhou Wu Chinese (Jinqu Wu) Xuanzhou Wu Chinese Chuqu Wu Chinese (Shangli Wu) Oujiang Wu / Ouyu Chinese The highest priority is Oujiang. (b) Referring to the criteria given above, give the rationale for splitting the existing code element into two or more languages: The varieties of Wu are not mutually intelligible. -

Map by Steve Huffman Data from World Language Mapping System 16

Mandarin Chinese Evenki Oroqen Tuva China Buriat Russian Southern Altai Oroqen Mongolia Buriat Oroqen Russian Evenki Russian Evenki Mongolia Buriat Kalmyk-Oirat Oroqen Kazakh China Buriat Kazakh Evenki Daur Oroqen Tuva Nanai Khakas Evenki Tuva Tuva Nanai Languages of China Mongolia Buriat Tuva Manchu Tuva Daur Nanai Russian Kazakh Kalmyk-Oirat Russian Kalmyk-Oirat Halh Mongolian Manchu Salar Korean Ta tar Kazakh Kalmyk-Oirat Northern UzbekTuva Russian Ta tar Uyghur SalarNorthern Uzbek Ta tar Northern Uzbek Northern Uzbek RussianTa tar Korean Manchu Xibe Northern Uzbek Uyghur Xibe Uyghur Uyghur Peripheral Mongolian Manchu Dungan Dungan Dungan Dungan Peripheral Mongolian Dungan Kalmyk-Oirat Manchu Russian Manchu Manchu Kyrgyz Manchu Manchu Manchu Northern Uzbek Manchu Manchu Manchu Manchu Manchu Korean Kyrgyz Northern Uzbek West Yugur Peripheral Mongolian Ainu Sarikoli West Yugur Manchu Ainu Jinyu Chinese East Yugur Ainu Kyrgyz Ta jik i Sarikoli East Yugur Sarikoli Sarikoli Northern Uzbek Wakhi Wakhi Kalmyk-Oirat Wakhi Kyrgyz Kalmyk-Oirat Wakhi Kyrgyz Ainu Tu Wakhi Wakhi Khowar Tu Wakhi Uyghur Korean Khowar Domaaki Khowar Tu Bonan Bonan Salar Dongxiang Shina Chilisso Kohistani Shina Balti Ladakhi Japanese Northern Pashto Shina Purik Shina Brokskat Amdo Tibetan Northern Hindko Kashmiri Purik Choni Ladakhi Changthang Gujari Kashmiri Pahari-Potwari Gujari Japanese Bhadrawahi Zangskari Kashmiri Baima Ladakhi Pangwali Mandarin Chinese Churahi Dogri Pattani Gahri Japanese Chambeali Tinani Bhattiyali Gaddi Kanashi Tinani Ladakhi Northern Qiang -

ISO 639-3 Code Split Request Template

ISO 639-3 Registration Authority Request for Change to ISO 639-3 Language Code Change Request Number: 2019-065 (completed by Registration authority) Date: August 31, 2019 Primary Person submitting request: Kirk Miller Affiliation: E-mail address: kirkmiller at gmail dot com Names, affiliations and email addresses of additional supporters of this request: Postal address for primary contact person for this request (in general, email correspondence will be used): PLEASE NOTE: This completed form will become part of the public record of this change request and the history of the ISO 639-3 code set and will be posted on the ISO 639-3 website. Types of change requests This form is to be used in requesting changes (whether creation, modification, or deletion) to elements of the ISO 639 Codes for the representation of names of languages — Part 3: Alpha-3 code for comprehensive coverage of languages. The types of changes that are possible are to 1) modify the reference information for an existing code element, 2) propose a new macrolanguage or modify a macrolanguage group; 3) retire a code element from use, including merging its scope of denotation into that of another code element, 4) split an existing code element into two or more new language code elements, or 5) create a new code element for a previously unidentified language variety. Fill out section 1, 2, 3, 4, or 5 below as appropriate, and the final section documenting the sources of your information. The process by which a change is received, reviewed and adopted is summarized on the final page of this form. -

Production and Consumption of Chinese Enamelled Porcelain, C.1728-C.1780

A Thesis Submitted for the Degree of PhD at the University of Warwick Permanent WRAP URL: http://wrap.warwick.ac.uk/91791 Copyright and reuse: This thesis is made available online and is protected by original copyright. Please scroll down to view the document itself. Please refer to the repository record for this item for information to help you to cite it. Our policy information is available from the repository home page. For more information, please contact the WRAP Team at: [email protected] warwick.ac.uk/lib-publications ‘The colours of each piece’: production and consumption of Chinese enamelled porcelain, c.1728-c.1780 Tang Hui A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History University of Warwick, Department of History March 2017 Declaration I, Tang Hui, confirm that this thesis is my own work and has not been submitted for a degree at another university. Cover Illustrations: Upper: Decorating porcelain in enamel colours, Album leaf, Watercolours, c.1750s. Hong Kong Maritime Museum, HKMM2012.0101.0021(detail). Lower: A Canton porcelain shop waiting for foreign customers. Album leaf, Watercolours, c.1750s, Hong Kong Maritime Museum, HKMM2012.0101.0033(detail). Table of Contents Declaration .............................................................................................................................. 2 Table of Contents ..................................................................................................................... i List of Illustrations -

Chinese in Indonesia: a Background Study

DigitalResources Electronic Survey Report 2011-028 ® Chinese in Indonesia: A Background Study Hermanto Lim David Mead Chinese in Indonesia: A Background Study Hermanto Lim and David Mead SIL International® 2011 SIL Electronic Survey Report 2011-028, March 2011 Copyright © 2011 Hermanto Lim, David Mead, and SIL International® All rights reserved 2 Contents Abstract 1 Introduction (by David Mead) 2 Introduction (by Hermanto Lim) 3 How should I address my Chinese neighbor? 3.1 Tionghoa 3.2 Cina 3.3 Teng Lang 3.4 WNI Keturunan 3.5 Nonpribumi 3.6 Chinese 3.7 Summary 4 Old and new Chinese immigrants in the archipelago 4.1 Overview of Chinese immigration 4.2 Peranakan versus Totok 4.3 Characteristics of Peranakan versus Totok 5 Chinese languages and dialects in Indonesia 5.1 Hokkien 5.2 Cantonese 5.3 Hakka 5.4 Teochew 5.5 Hainan 5.6 Hokchiu 5.7 Henghua 5.8 Hokchhia 5.9 Kwongsai 5.10 Chao An 5.11 Luichow 5.12 Shanghai 5.13 Ningpo 5.14 Mandarin 6 Government policy toward Chinese writing and Chinese languages Appendix: Some notes about written Chinese References 3 Abstract In this document we discuss the fourteen major varieties of Chinese which are reported to be spoken in the country of Indonesia, giving particular attention to the five largest communities: Hokkien, Cantonese, Hakka, Teochew, and Hainan. Additional sections discuss terms which have been used in the Indonesian context for referring to people of Chinese descent, overview of Chinese immigration into Indonesia over the previous centuries, and recent government policy toward Chinese languages and Chinese writing.