A Tough Construction Analysis of the Shanghainese “Passive”

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Tonatory Patterns in Taizhou Wu Tones

TONATORY PATTERNS IN TAIZHOU WU TONES Phil Rose Emeritus Faculty, Australian National University [email protected] ABSTRACT 台州 subgroup of Wu to which Huángyán belongs. The issue has significance within descriptive Recordings of speakers of the Táizhou subgroup of tonetics, tonatory typology and historical linguistics. Wu Chinese are used to acoustically document an Wu dialects – at least the conservative varieties – interaction between tone and phonation first attested show a wide range of tonatory behaviour [11]. One in 1928. One or two of their typically seven or eight finds breathy or ventricular phonation in groups of tones are shown to have what sounds like a mid- tones characterising natural tonal classes of Rhyme glottal-stop, thus demonstrating a new importance for phonotactics and Wu’s complex tone pattern in Wu tonatory typology. Possibly reflecting sandhi. One also finds a single tone characterised by gradual loss, larygealisation appears restricted to the a different non-modal phonation type [12]; or even north and north-west, and is absent in Huángyán two different non-modal phonation types in two dialect where it was first described. A perturbatory tones. However, the Huangyan-type tonation seems model of the larygealisation is tested in an to involve a new variation, with the same phonation experiment determining how much of the complete type in two different tones from the same historical tonal F0 contour can be restored from a few tonal category, thus prompting speculation that it centiseconds of modal F0 at Rhyme onset and offset. developed before the tonal split. The results are used both to acoustically quantify laryngealised tonal F0, with its problematic jitter and 2. -

Shanghainese Vowel Merger Reversal Full Title

0 Short title: Shanghainese vowel merger reversal Full title: On the cognitive basis of contact-induced sound change: Vowel merger reversal in Shanghainese Names, affiliations, and email addresses of authors: Yao Yao The Hong Kong Polytechnic University [email protected] Charles B. Chang Boston University [email protected] Address for correspondence: Yao Yao The Hong Kong Polytechnic University Department of Chinese and Bilingual Studies Hung Hom, Kowloon, Hong Kong 1 Short title: Shanghainese vowel merger reversal Full title: On the cognitive basis of contact-induced sound change: Vowel merger reversal in Shanghainese 2 Abstract This study investigated the source and status of a recent sound change in Shanghainese (Wu, Sinitic) that has been attributed to language contact with Mandarin. The change involves two vowels, /e/ and /ɛ/, reported to be merged three decades ago but produced distinctly in contemporary Shanghainese. Results of two production experiments showed that speaker age, language mode (monolingual Shanghainese vs. bilingual Shanghainese-Mandarin), and crosslinguistic phonological similarity all influenced the production of these vowels. These findings provide evidence for language contact as a linguistic means of merger reversal and are consistent with the view that contact phenomena originate from cross-language interaction within the bilingual mind.* Keywords: merger reversal, language contact, bilingual processing, phonological similarity, crosslinguistic influence, Shanghainese, Mandarin. * This research was supported by -

De Sousa Sinitic MSEA

THE FAR SOUTHERN SINITIC LANGUAGES AS PART OF MAINLAND SOUTHEAST ASIA (DRAFT: for MPI MSEA workshop. 21st November 2012 version.) Hilário de Sousa ERC project SINOTYPE — École des hautes études en sciences sociales [email protected]; [email protected] Within the Mainland Southeast Asian (MSEA) linguistic area (e.g. Matisoff 2003; Bisang 2006; Enfield 2005, 2011), some languages are said to be in the core of the language area, while others are said to be periphery. In the core are Mon-Khmer languages like Vietnamese and Khmer, and Kra-Dai languages like Lao and Thai. The core languages generally have: – Lexical tonal and/or phonational contrasts (except that most Khmer dialects lost their phonational contrasts; languages which are primarily tonal often have five or more tonemes); – Analytic morphological profile with many sesquisyllabic or monosyllabic words; – Strong left-headedness, including prepositions and SVO word order. The Sino-Tibetan languages, like Burmese and Mandarin, are said to be periphery to the MSEA linguistic area. The periphery languages have fewer traits that are typical to MSEA. For instance, Burmese is SOV and right-headed in general, but it has some left-headed traits like post-nominal adjectives (‘stative verbs’) and numerals. Mandarin is SVO and has prepositions, but it is otherwise strongly right-headed. These two languages also have fewer lexical tones. This paper aims at discussing some of the phonological and word order typological traits amongst the Sinitic languages, and comparing them with the MSEA typological canon. While none of the Sinitic languages could be considered to be in the core of the MSEA language area, the Far Southern Sinitic languages, namely Yuè, Pínghuà, the Sinitic dialects of Hǎinán and Léizhōu, and perhaps also Hakka in Guǎngdōng (largely corresponding to Chappell (2012, in press)’s ‘Southern Zone’) are less ‘fringe’ than the other Sinitic languages from the point of view of the MSEA linguistic area. -

Official Colours of Chinese Regimes: a Panchronic Philological Study with Historical Accounts of China

TRAMES, 2012, 16(66/61), 3, 237–285 OFFICIAL COLOURS OF CHINESE REGIMES: A PANCHRONIC PHILOLOGICAL STUDY WITH HISTORICAL ACCOUNTS OF CHINA Jingyi Gao Institute of the Estonian Language, University of Tartu, and Tallinn University Abstract. The paper reports a panchronic philological study on the official colours of Chinese regimes. The historical accounts of the Chinese regimes are introduced. The official colours are summarised with philological references of archaic texts. Remarkably, it has been suggested that the official colours of the most ancient regimes should be the three primitive colours: (1) white-yellow, (2) black-grue yellow, and (3) red-yellow, instead of the simple colours. There were inconsistent historical records on the official colours of the most ancient regimes because the composite colour categories had been split. It has solved the historical problem with the linguistic theory of composite colour categories. Besides, it is concluded how the official colours were determined: At first, the official colour might be naturally determined according to the substance of the ruling population. There might be three groups of people in the Far East. (1) The developed hunter gatherers with livestock preferred the white-yellow colour of milk. (2) The farmers preferred the red-yellow colour of sun and fire. (3) The herders preferred the black-grue-yellow colour of water bodies. Later, after the Han-Chinese consolidation, the official colour could be politically determined according to the main property of the five elements in Sino-metaphysics. The red colour has been predominate in China for many reasons. Keywords: colour symbolism, official colours, national colours, five elements, philology, Chinese history, Chinese language, etymology, basic colour terms DOI: 10.3176/tr.2012.3.03 1. -

From Eurocentrism to Sinocentrism: the Case of Disposal Constructions in Sinitic Languages

From Eurocentrism to Sinocentrism: The case of disposal constructions in Sinitic languages Hilary Chappell 1. Introduction 1.1. The issue Although China has a long tradition in the compilation of rhyme dictionar- ies and lexica, it did not develop its own tradition for writing grammars until relatively late.1 In fact, the majority of early grammars on Chinese dialects, which begin to appear in the 17th century, were written by Europe- ans in collaboration with native speakers. For example, the Arte de la len- gua Chiõ Chiu [Grammar of the Chiõ Chiu language] (1620) appears to be one of the earliest grammars of any Sinitic language, representing a koine of urban Southern Min dialects, as spoken at that time (Chappell 2000).2 It was composed by Melchior de Mançano in Manila to assist the Domini- cans’ work of proselytizing to the community of Chinese Sangley traders from southern Fujian. Another major grammar, similarly written by a Do- minican scholar, Francisco Varo, is the Arte de le lengua mandarina [Grammar of the Mandarin language], completed in 1682 while he was living in Funing, and later posthumously published in 1703 in Canton.3 Spanish missionaries, particularly the Dominicans, played a signifi- cant role in Chinese linguistic history as the first to record the grammar and lexicon of vernaculars, create romanization systems and promote the use of the demotic or specially created dialect characters. This is discussed in more detail in van der Loon (1966, 1967). The model they used was the (at that time) famous Latin grammar of Elio Antonio de Nebrija (1444–1522), Introductiones Latinae (1481), and possibly the earliest grammar of a Ro- mance language, Grammatica de la Lengua Castellana (1492) by the same scholar, although according to Peyraube (2001), the reprinted version was not available prior to the 18th century. -

The Phonological Domain of Tone in Chinese: Historical Perspectives

THE PHONOLOGICAL DOMAIN OF TONE IN CHINESE: HISTORICAL PERSPECTIVES by Yichun Dai B. A. Nanjing University, 1982 THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGRFE OF MASTER OF ARTS In the pepartment of Linguistics @ Yichun Dai 1991 SIMON FRASER UNIVERSITY July 1991 All rights reserved. This work may not be reproduced in whole or in part, by photocopy or other means, without permission of the author. APPROVAL NAME: Yichun Dai DEGREE: Master of Arts (Linguistics) TITLE OF THESIS : The Phonological Domain of Tone in Chinese: Historical Perspectives EXAMINING COMMITTEE: Chairman: Dr. R. C. DeArmond ----------- Dr. T. A. Perry, Senior ~aisor Dr. N. J. Lincoln - ................................... J A. Edmondson, Professor, Department of foreign Languages and Linguistics, University of Texas at Arlington, External Examiner PARTIAL COPYR l GHT L l CENSE I hereby grant to Simon Fraser University the right to lend my thesis, project or extended essay (the title of which is shown below) to users of the Simon Fraser University L ibrary, and to make partial or single copies only for such users or in response to a request from the library of any other university, or other educational institution, on its own behalf or for one of its users. I further agree that permission for multiple copying of this work for scholarly purposes may be granted by me or the Dean of Graduate Studies. It is understood that copying or publication of this work for financial gain shall not be allowed without my written permission. Title of Thesis/Project/Extended Essay Author: (signature) (name 1 Abstract This thesis demonstrates how autosegmental licensing theory operates in Chinese. -

LANGUAGE CONTACT and AREAL DIFFUSION in SINITIC LANGUAGES (Pre-Publication Version)

LANGUAGE CONTACT AND AREAL DIFFUSION IN SINITIC LANGUAGES (pre-publication version) Hilary Chappell This analysis includes a description of language contact phenomena such as stratification, hybridization and convergence for Sinitic languages. It also presents typologically unusual grammatical features for Sinitic such as double patient constructions, negative existential constructions and agentive adversative passives, while tracing the development of complementizers and diminutives and demarcating the extent of their use across Sinitic and the Sinospheric zone. Both these kinds of data are then used to explore the issue of the adequacy of the comparative method to model linguistic relationships inside and outside of the Sinitic family. It is argued that any adequate explanation of language family formation and development needs to take into account these different kinds of evidence (or counter-evidence) in modeling genetic relationships. In §1 the application of the comparative method to Chinese is reviewed, closely followed by a brief description of the typological features of Sinitic languages in §2. The main body of this chapter is contained in two final sections: §3 discusses three main outcomes of language contact, while §4 investigates morphosyntactic features that evoke either the North-South divide in Sinitic or areal diffusion of certain features in Southeast and East Asia as opposed to grammaticalization pathways that are crosslinguistically common.i 1. The comparative method and reconstruction of Sinitic In Chinese historical -

Oujiang Wu Tones and Acoustic Reconstruction

OUJIANG WU TONES AND ACOUSTIC RECONSTRUCTION PHIL ROSE Linguistics (Arts), Australian National University 1. Introduction We do not expect tones, as phonological phenomena, to vary without limit, but to show similarities, or so-called tonological universals, across varieties (Maddieson 1978). Nevertheless, when one samples tones from different Asian tone languages, or even different dialects, they often show a great variety of pitch shapes. Zhu and Rose (1998) for example demonstrated no less than 25 different tones in four varieties from different sub-groups within the Wu dialects of east central China. (I use the term tone in this paper in a sense analogous to phone, that is, as a constellation of audibly different properties, with pitch predominating but also including length and phonation type, that constitutes observation data for phonological – usually tonemic – analysis.) In exploring the nature of phonological variation in Language, we naturally concentrate on differences. This paper, on the other hand, makes use of how similar tones can be. It looks at variation in tones at seven localities distributed over a fairly small geographical area where the varieties, which belong to the same dialectal sub-group, have been described as homogeneous. Although this study reveals some interesting synchronic linguistic-tonetic variation, the main reason for undertaking it is not typological, but, as befits a festschrift for Harold Koch, historical. As mentioned, the Wu dialects of Chinese are well-known for their tonal complexity. Not only do they exhibit probably the most complex tone sandhi in the world (Rose 1990), but they also show a bewildering variety in their citation tones. -

Autonomy of Chinese Judges: Dynamics of People’S Courts, the Ccp and the Public in Contemporary Judicial Reform

AUTONOMY OF CHINESE JUDGES: DYNAMICS OF PEOPLE’S COURTS, THE CCP AND THE PUBLIC IN CONTEMPORARY JUDICIAL REFORM by YUE LIU LL.B., Jilin University, 2003 LL.M., Jilin University, 2006 A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE AND POSTDOCTORAL STUDIES (Law) THE UNIVERSITY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA (Vancouver) November 2016 © Yue Liu, 2016 Abstract This dissertation is the outcome of author’s observations and empirical research on judicial reform in China from the 1980s to 2015. Focusing on judicial decision making process of judges in Chinese courts, it attempts to answer the following questions: How do the Chinese Communist Party (CCP), the public, and the internal administrative power—three factors essential to Chinese judges’ judicial decision making process— influence the adjudication of individual cases in various periods of judicial reform? How do the increasingly professionalized judges respond to these institutionalized challenges? Moreover, how do the dynamics generated from the interactions among courts, the CCP, and the public shape the norms and institutional building of judges and courts, and affect judicial reform policies in China? This dissertation adopts historical analysis, documentary analysis, and qualitative analysis to seek answers to these questions. It finds that, first, direct influence of the CCP and the public to the judicial behaviours of individual judges is less evident than indirect influence through the administrative oversight in courts’ internal bureaucracy. Second, the relationships between courts, the CCP, and the public are more dynamic in fragmented China. The norms of Chinese judges’ autonomy and institutional changes in courts are constantly shaped by the expectations and compromise of powers of the CCP, the public, and courts. -

Lesson Plan Chien-Shiung Wu, Chinese Nuclear Physicist

Lesson Plan Chien-Shiung Wu, Chinese Nuclear Physicist Chien-Shiung Wu assembling an electro-static generator at Smith College Physics Laboratory. Photo courtesy of AIP Emilio Segre Visual Archives. Grade Level(s): 9-12 Subject(s): History, Physics In-Class Time: 50-65 minutes Prep Time: 10-15 minutes Materials • A/V equipment • Copies of Chien-Shiung Wu excerpt from The New Dictionary of Scientific Biography (found in the Supplemental Materials) • Copies of Discussion Questions (found in the Supplemental Materials) Prepared by the Center for the History of Physics at AIP 1 Objective In this lesson, students will learn about the life of experimental nuclear physicist Chien-Shiung Wu. Born in China, she became a hugely influential subatomic physicist after immigrating to America in the 1930s. Rather than focusing on her scientific accomplishments (which are discussed in more detail in the AIP Teacher’s Guides “Fair or Unfair: Should These Women Have Won Nobel Prizes” and “Outcasts and Opportunities: The Effects of World War II on the Careers of Female Physicists”), this lesson has students read about Chien-Shiung Wu’s early life, education, and unlikely activism. Introduction Chien-Shiung Wu (C.S. Wu) was born near Shanghai, China on May 31, 1912. She attended the Ming De School in her youth, which her father founded as one of the earliest Chinese schools to admit girls. Ultimately in 1930, she enrolled in the National Central University in Nanjing, where four years later she earned her Bachelor of Science degree in physics at the top of her class. 1 Wu’s time at Nanjing coincided with Japan’s invasion of the northern Chinese province Manchuria and subsequent attempts to destabilize the Chinese government. -

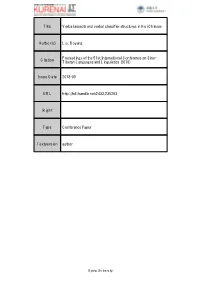

Title Verbal Aspects and Verbal Classifier Structures in Hui Chinese

Title Verbal aspects and verbal classifier structures in Hui Chinese Author(s) Liu, Boyang Proceedings of the 51st International Conference on Sino- Citation Tibetan Languages and Linguistics (2018) Issue Date 2018-09 URL http://hdl.handle.net/2433/235293 Right Type Conference Paper Textversion author Kyoto University Verbal Aspects and Verbal Classifier Structures in Hui Chinese LIU Boyang (EHESS-CRLAO) CONTENT • PART I: Research Purpose • PART II: The definition and classification of VCLs in Sinitic languages – 1. An introduction to Hui Chinese – 2. Previous work on VCLs in Mandarin – 3. A provisional definition and classification of VCLs in Sinitic languages – 4. Lexical aspects indicated by the verb phrase [VERB-VCLP] in Sinitic languages – 5. Relationships between grammatical aspects and the verb phrase [VERB-VCLP- OBJECT] • PART III: Grammatical aspects indicated by special auto-verbal classifier (Auto-VCL) structures in Hui Chinese – 6. The perfective aspect – 7. The imperfective aspect • PART IV: Conclusion PART I: RESEARCH PURPOSE Research Purpose: • Verbal classifiers (VCLs) have been much less studied from a typological perspective than the category of nominal classifiers (NCLs), and even less in the non-Mandarin branches of Sinitic languages, such as the Hui dialects; • In this study, I will introduce relationships between lexical aspects, grammatical aspects and verbal classifier phrases (VCLPs) in Hui Chinese, analyzing the similarities and differences with Standard Mandarin. • Verbal classifier structures in the Hui dialects display a transitional feature compared with Xiang, Gan and Wu, taking auto-verbal classifier (Auto-VCL) structures as examples (auto-VCLs derive from verb reduplicants in the verb phrase [VERB- (‘one’)-VERB]): – Auto-VCLs in the verb phrase [VERB-AUTO VCL] can code the perfective or imperfective aspect in different types of complex sentences in Hui Chinese; – More variety of auto-VCL structures is found in Hui Chinese compared with Xiang and Gan dialects. -

The Social Role of Shanghainese in Shanghai

Robert D. Angus California State University, Fullerton Prestige and the local dialect: 1 The social role of Shanghainese in Shanghai Abstract. Shanghai lies in the Wu dialect area in east central China. Whereas Modern Standard Chinese is the prescribed national standard in instruction, broadcasting, and commerce, a specific variety that descended from Wu is the native language of the city. We are accustomed to finding that local varieties experience a diminution of prestige in such circumstances. The social and historical circumstances of Shanghai, however, uniquely create a situation in which this is not the case. In this paper I will briefly discuss the history of the city and its development, trace social attitudes (and ideas of prestige) on the part of its natives, show how the use of the local variety indexes social status and prestige among residents of the city, and provide evidence that the use of the native dialect of Shanghai is neither transitional nor restricted to the spheres heretofore considered Low in the typical diglossia situation. Introduction When a local, minority language is used alongside a national variety, especially when the national language is upheld as a standard, the local variety is generally seen to suffer in prestige. In a diglossia situation, as outlined by Ferguson in his groundbreaking article, the two varieties are complementarily distributed among social situations, and the prestige variety is identified as the one used in all AHigh@ circumstances. Most familiar, writes Ferguson, is the situation in California Linguistic Notes Volume XXVII No. 2 Fall, 2002 2 which “many speakers speak their local dialect at home or among family or friends of the same dialect area but use the standard language in communicating with speakers of other dialects or on public occasions” (1959:325).