Production and Consumption of Chinese Enamelled Porcelain, C.1728-C.1780

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Tracing the Origin of Blue and White Chinese Porcelain Ordered for the Portuguese Market During the Ming Dynasty Using INAA

Journal of Archaeological Science 40 (2013) 3046e3057 Contents lists available at SciVerse ScienceDirect Journal of Archaeological Science journal homepage: http://www.elsevier.com/locate/jas Tracing the origin of blue and white Chinese Porcelain ordered for the Portuguese market during the Ming dynasty using INAA M. Isabel Dias a,*, M. Isabel Prudêncio a, M.A. Pinto De Matos b, A. Luisa Rodrigues a a Campus Tecnológico e Nuclear/Instituto Superior Técnico, Universidade Técnica de Lisboa, EN 10 (Km 139,7), 2686-953 Sacavém, Portugal b Museu Nacional do Azulejo, Rua da Madre de Deus no 4, 1900-312 Lisboa, Portugal article info abstract Article history: The existing documentary history of Chinese porcelain ordered for the Portuguese market (mainly Ming Received 21 March 2012 dynasty.) is reasonably advanced; nevertheless detailed laboratory analyses able to reveal new aspects Received in revised form like the number and/or diversity of producing centers involved in the trade with Portugal are lacking. 26 February 2013 In this work, the chemical characterization of porcelain fragments collected during recent archaeo- Accepted 3 March 2013 logical excavations from Portugal (Lisbon and Coimbra) was done for provenance issues: identification/ differentiation of Chinese porcelain kilns used. Chemical analysis was performed by instrumental Keywords: neutron activation analysis (INAA) using the Portuguese Research Reactor. Core samples were taken from Ancient Chinese porcelain for Portuguese market the ceramic body avoiding contamination form the surface layers constituents. The results obtained so INAA far point to: (1) the existence of three main chemical-based clusters; and (2) a general attribution of the Chemical composition porcelains studied to southern China kilns; (3) a few samples are specifically attributed to Jingdezhen Ming dynasty and Zhangzhou kiln sites. -

'A Mind to Copy': Inspired by Meissen

‘A Mind to Copy’: Inspired by Meissen Anton Gabszewicz Independent Ceramic Historian, London Figure 1. Sir Charles Hanbury Williams by John Giles Eccardt. 1746 (National Portrait Gallery, London.) 20 he association between Nicholas Sprimont, part owner of the Chelsea Porcelain Manufactory, Sir Everard Fawkener, private sec- retary to William Augustus, Duke of Cumberland, the second son of King George II, and Sir Charles Hanbury Williams, diplomat and Tsometime British Envoy to the Saxon Court at Dresden was one that had far-reaching effects on the development and history of the ceramic industry in England. The well-known and oft cited letter of 9th June 1751 from Han- bury Williams (fig. 1) to his friend Henry Fox at Holland House, Kensington, where his china was stored, sets the scene. Fawkener had asked Hanbury Williams ‘…to send over models for different Pieces from hence, in order to furnish the Undertakers with good designs... But I thought it better and cheaper for the manufacturers to give them leave to take away any of my china from Holland House, and to copy what they like.’ Thus allowing Fawkener ‘… and anybody He brings with him, to see my China & to take away such pieces as they have a mind to Copy.’ The result of this exchange of correspondence and Hanbury Williams’ generous offer led to an almost instant influx of Meissen designs at Chelsea, a tremendous impetus to the nascent porcelain industry that was to influ- ence the course of events across the industry in England. Just in taking a ca- sual look through the products of most English porcelain factories during Figure 2. -

Views of a Porcelain 15

THE INFLUENCE OF GLASS TECHNOLOGY vessels nor to ceramic figurines, but to beads made in imitation of imported glass.10 The original models were ON CHINESE CERAMICS eye-beads of a style produced at numerous sites around the Mediterranean, in Central Asia and also in southern Russia, and current in the Near East since about 1500 Nigel Wood BC.11 A few polychrome glass beads found their way to Research Laboratory for Archaeology and the History of Art, University of Oxford. China in the later Bronze Age, including one example excavated from a Spring and Autumn period (770-476 BC) site in Henan province.12 This particular blue and ONE OF THE MOST IMPORTANT AND ENDURING DIFFER- white eye bead was of a style current in the eastern ences between the ceramics of China and the Near East Mediterranean in the 6th to 3rd century BC and proved lies in the role that glass has played in the establishment to have been coloured by such sophisticated, but of their respective ceramic traditions. In the ceramics of typically Near Eastern, chromophores as calcium- Mesopotamia, Persia, Egypt, and Syria glass technology antimonate-white, cobalt-blue and a copper-turquoise, proved vital for the development of glazed ceramics. while its glass was of the soda-lime type, common in 13 Figure 2. Earthenware jar with weathered glazes. Warring States Following the appearance of glazed stone-based the ancient world. period. Probably 3rd century BC (height: 9.5 cm). The British ceramics in the fourth millennium BC, the first glazes These ‘western’ beads would have been wonders in Museum. -

A Detective Story: Meissen Porcelains Copying East Asian Models. Fakes Or Originals in Their Own Right?

A detective story: Meissen porcelains copying East Asian models. Fakes or originals in their own right? Julia Weber, Keeper of Ceramics at the Bavarian National Museum, Munich he ‘detective story’ I want to tell relates to how the French mer- fact that Saxon porcelain was the first in Europe to be seriously capable of chant Rodolphe Lemaire managed, around 1730, to have accurate competing with imported goods from China and Japan. Indeed, based on their copies of mostly Japanese porcelain made at Meissen and to sell high-quality bodies alone, he appreciated just how easily one might take them them as East Asian originals in Paris. I will then follow the trail of for East Asian originals. This realisation inspired Lemaire to embark on a new Tthe fakes and reveal what became of them in France. Finally, I will return business concept. As 1728 drew to a close, Lemaire travelled to Dresden. He briefly to Dresden to demonstrate that the immediate success of the Saxon bought Meissen porcelains in the local warehouse in the new market place copies on the Parisian art market not only changed how they were regarded and ordered more in the manufactory. In doing this he was much the same in France but also in Saxony itself. as other merchants but Lemaire also played a more ambitious game: in a bold Sometime around 1728, Lemaire, the son of a Parisian family of marchand letter he personally asked Augustus the Strong, Elector of Saxony and of faïencier, became acquainted with Meissen porcelain for the first time whilst Poland, to permit an exclusive agreement with the Meissen manufactory. -

From the Lands of Asia

Education Programs 2 3 TABLE OF CONTENTS Preparing students in advance p. 4 Vocabulary and pronunciation guide pp. 5–8 About the exhibition p. 9 The following thematic sections include selected objects, discussion questions, and additional resources. I. Costumes and Customs pp. 10–12 II. An Ocean of Porcelain pp. 13–15 III. A Thousand Years of Buddhism pp. 16–19 IV. The Magic of Jade pp. 20–23 Artwork reproductions pp. 24–32 4 PREPARING STUDENTS IN ADVANCE We look forward to welcoming your school group to the Museum. Here are a few suggestions for teachers to help to ensure a successful, productive learning experience at the Museum. LOOK, DISCUSS, CREATE Use this resource to lead classroom discussions and related activities prior to the visit. (Suggested activities may also be used after the visit.) REVIEW MUSEUM GUIDELINES For students: • Touch the works of art only with your eyes, never with your hands. • Walk in the museum—do not run. • Use a quiet voice when sharing your ideas. • No flash photography is permitted in special exhibitions or permanent collection galleries. • Write and draw only with pencils—no pens or markers, please. Additional information for teachers: • Please review the bus parking information provided with your tour confirmation. • Backpacks, umbrellas, or other bulky items are not allowed in the galleries. Free parcel check is available. • Seeing-eye dogs and other service animals assisting people with disabilities are the only animals allowed in the Museum. • Unscheduled lecturing to groups is not permitted. • No food, drinks, or water bottles are allowed in any galleries. -

Karbury's Auction House

Karbury's Auction House Antiques Estates & Collection Sale Saturday - September 8, 2018 Antiques Estates & Collection Sale 307: A Chinese Gilt Bronze Buddhist Figure USD 300 - 500 308: A Set of Four Bronze Cups USD 200 - 300 309: A Song Style Jizhou Tortoiseshell-Glazed Tea Bowl USD 1,000 - 2,000 310: A Bronze Snake Sculpture USD 100 - 200 311: A Wood Pillow with Bone Inlaid USD 100 - 200 312: A Carved Ink Stone USD 200 - 300 313: A Stone Carved Head of Buddha USD 100 - 200 314: A Doucai Chicken Cup with Yongzheng Mark USD 500 - 700 Bid Live Online at LiveAuctioneers.com Page 1 Antiques Estates & Collection Sale 315: A Jian Ware Tea Bowl in Silver Hare Fur Streak USD 800 - 1,500 316: A Celadon Glazed Double Gourd Vase USD 400 - 600 317: Three Porcelain Dog Figurines USD 200 - 400 318: A Jun ware flower Pot USD 1,500 - 2,000 319: A Pair of Famille Rose Jars with Cover USD 800 - 1,200 320: A Blanc-De-Chine Figure of Seated Guanyin USD 1,500 - 2,000 321: A Pair of Vintage Porcelain Lamps USD 200 - 300 322: A Chicken Head Spout Ewer USD 800 - 1,200 Bid Live Online at LiveAuctioneers.com Page 2 Antiques Estates & Collection Sale 323: Two sancai figures and a ceramic cat-motif pillow USD 200 - 300 324: A Teadust Glazed Vase with Qianlong Mark USD 500 - 800 325: A Rosewood Tabletop Curio Display Stand USD 300 - 500 326: A Blue and White Celadon Glazed Vase USD 300 - 500 327: A Wucai Dragon Jar with Cover USD 300 - 500 328: A Green and Aubergine-Enameled Yellow-Ground Vase USD 200 - 300 329: A Celadon Square Sectioned Dragon Vase USD 200 - 300 -

Resolving the Incommensurability of Eugenics & the Quantified Self

Eugenics & the Quantified Self Resolving the Incommensurability of Eugenics & the Quantified Self Gabi Schaffzin The “quantified self,” a cultural phenomenon which emerged just before the 2010s, embodies one critical underlying tenet: self-tracking for the purpose of self-improvement through the identification of behavioral and environmental variables critical to one’s physical and psychological makeup. Of course, another project aimed at systematically improving persons through changes to the greater population is eugenics. Importantly, both cultural phenomena are built on the predictive power of correlation and regression—statistical technologies that classify and normalize. Still, a closer look at the late-nineteenth and early-twentieth century eugenic projects and the early-twenty-first century proliferation of quantified self devices reveals an inherent incommensurability between the fundamental tenets underlying each movement. Eugenics, with its emphasis on hereditary physical and psychological traits, precludes the possibility that outside influences may lead to changes in an individual’s bodily or mental makeup. The quantified self, on the other hand, is predicated on the belief that, by tracking the variables associated with one’s activities or environment, one might be able to make adjustments to achieve physical or psychological health. By understanding how the technologies of the two movements work in the context of the predominant form of Foucauldian governmentality and biopower of their respective times, however, the incommensurability between these two movements might in fact be resolved. I'm Gabi Schaffzin from UC San Diego and I'm pursuing my PhD in Art History, Theory, and Criticism with an Art Practice concentration. My work focuses on the designed representation of measured pain in a medical, laboratory, and consumer context. -

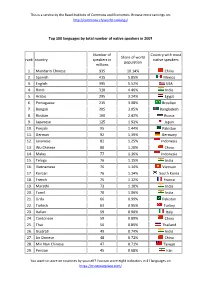

Top 100 Languages by Total Number of Native Speakers in 2007 Rank

This is a service by the Basel Institute of Commons and Economics. Browse more rankings on: http://commons.ch/world-rankings/ Top 100 languages by total number of native speakers in 2007 Number of Country with most Share of world rank country speakers in native speakers population millions 1. Mandarin Chinese 935 10.14% China 2. Spanish 415 5.85% Mexico 3. English 395 5.52% USA 4. Hindi 310 4.46% India 5. Arabic 295 3.24% Egypt 6. Portuguese 215 3.08% Brasilien 7. Bengali 205 3.05% Bangladesh 8. Russian 160 2.42% Russia 9. Japanese 125 1.92% Japan 10. Punjabi 95 1.44% Pakistan 11. German 92 1.39% Germany 12. Javanese 82 1.25% Indonesia 13. Wu Chinese 80 1.20% China 14. Malay 77 1.16% Indonesia 15. Telugu 76 1.15% India 16. Vietnamese 76 1.14% Vietnam 17. Korean 76 1.14% South Korea 18. French 75 1.12% France 19. Marathi 73 1.10% India 20. Tamil 70 1.06% India 21. Urdu 66 0.99% Pakistan 22. Turkish 63 0.95% Turkey 23. Italian 59 0.90% Italy 24. Cantonese 59 0.89% China 25. Thai 56 0.85% Thailand 26. Gujarati 49 0.74% India 27. Jin Chinese 48 0.72% China 28. Min Nan Chinese 47 0.71% Taiwan 29. Persian 45 0.68% Iran You want to score on countries by yourself? You can score eight indicators in 41 languages on https://trustyourplace.com/ This is a service by the Basel Institute of Commons and Economics. -

Cantonese Vs. Mandarin: a Summary

Cantonese vs. Mandarin: A summary JMFT October 21, 2015 This short essay is intended to summarise the similarities and differences between Cantonese and Mandarin. 1 Introduction The large geographical area that is referred to as `China'1 is home to many languages and dialects. Most of these languages are related, and fall under the umbrella term Hanyu (¡£), a term which is usually translated as `Chinese' and spoken of as though it were a unified language. In fact, there are hundreds of dialects and varieties of Chinese, which are not mutually intelligible. With 910 million speakers worldwide2, Mandarin is by far the most common dialect of Chinese. `Mandarin' or `guanhua' originally referred to the language of the mandarins, the government bureaucrats who were based in Beijing. This language was based on the Bejing dialect of Chinese. It was promoted by the Qing dynasty (1644{1912) and later the People's Republic (1949{) as the country's lingua franca, as part of efforts by these governments to establish political unity. Mandarin is now used by most people in China and Taiwan. 3 Mandarin itself consists of many subvarities which are not mutually intelligible. Cantonese (Yuetyu (£) is named after the city Canton, whose name is now transliterated as Guangdong. It is spoken in Hong Kong and Macau (with a combined population of around 8 million), and, owing to these cities' former colonial status, by many overseas Chinese. In the rest of China, Cantonese is relatively rare, but it is still sometimes spoken in Guangzhou. 2 History and etymology It is interesting to note that the Cantonese name for Cantonese, Yuetyu, means `language of the Yuet people'. -

Ming Dynasty Porcelain Plate Laura G

Wonders of Nature and Artifice Art and Art History Fall 2017 Blue-and-White Wonder: Ming Dynasty Porcelain Plate Laura G. Waters '19, Gettysburg College Follow this and additional works at: https://cupola.gettysburg.edu/wonders_exhibit Part of the Ancient, Medieval, Renaissance and Baroque Art and Architecture Commons, Fine Arts Commons, History of Science, Technology, and Medicine Commons, Industrial and Product Design Commons, and the Intellectual History Commons Share feedback about the accessibility of this item. Waters, Laura G., "Blue-and-White Wonder: Ming Dynasty Porcelain Plate" (2017). Wonders of Nature and Artifice. 12. https://cupola.gettysburg.edu/wonders_exhibit/12 This is the author's version of the work. This publication appears in Gettysburg College's institutional repository by permission of the copyright owner for personal use, not for redistribution. Cupola permanent link: https://cupola.gettysburg.edu/wonders_exhibit/12 This open access student research paper is brought to you by The uC pola: Scholarship at Gettysburg College. It has been accepted for inclusion by an authorized administrator of The uC pola. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Blue-and-White Wonder: Ming Dynasty Porcelain Plate Abstract This authentic Ming Dynasty (1368-1644) plate is a prime example of early export porcelain, a luminous substance that enthralled European collectors. The eg nerous gift of oJ yce P. Bishop in honor of her daughter, Kimberly Bishop Connors, Ming Dynasty Blue-and-White Plate is on loan from the Reeves Collection at Washington and Lee University in Lexington, Virginia. The lp ate itself is approximately 7.75 inches (20 cm) in diameter, and appears much deeper from the bottom than it does from the top. -

Language Contact in Nanning: Nanning Pinghua and Nanning Cantonese

20140303 draft of : de Sousa, Hilário. 2015a. Language contact in Nanning: Nanning Pinghua and Nanning Cantonese. In Chappell, Hilary (ed.), Diversity in Sinitic languages, 157–189. Oxford: Oxford University Press. Do not quote or cite this draft. LANGUAGE CONTACT IN NANNING — FROM THE POINT OF VIEW OF NANNING PINGHUA AND NANNING CANTONESE1 Hilário de Sousa Radboud Universiteit Nijmegen, École des hautes études en sciences sociales — ERC SINOTYPE project 1 Various topics discussed in this paper formed the body of talks given at the following conferences: Syntax of the World’s Languages IV, Dynamique du Langage, CNRS & Université Lumière Lyon 2, 2010; Humanities of the Lesser-Known — New Directions in the Descriptions, Documentation, and Typology of Endangered Languages and Musics, Lunds Universitet, 2010; 第五屆漢語方言語法國際研討會 [The Fifth International Conference on the Grammar of Chinese Dialects], 上海大学 Shanghai University, 2010; Southeast Asian Linguistics Society Conference 21, Kasetsart University, 2011; and Workshop on Ecology, Population Movements, and Language Diversity, Université Lumière Lyon 2, 2011. I would like to thank the conference organizers, and all who attended my talks and provided me with valuable comments. I would also like to thank all of my Nanning Pinghua informants, my main informant 梁世華 lɛŋ11 ɬi55wa11/ Liáng Shìhuá in particular, for teaching me their language(s). I have learnt a great deal from all the linguists that I met in Guangxi, 林亦 Lín Yì and 覃鳳餘 Qín Fèngyú of Guangxi University in particular. My colleagues have given me much comments and support; I would like to thank all of them, our director, Prof. Hilary Chappell, in particular. Errors are my own. -

1 the Willow Pattern

The East India Company at Home, 1757-1857 – UCL History The Willow Pattern: Dunham Massey By Francesca D’Antonio Please note that this case study was first published on blogs.ucl.ac.uk/eicah in June 2014. For citation advice, visit: http://blogs.uc.ac.uk/eicah/usingthewebsite. Unlike other ‘objects studies’ featured in the East India Company At Home 1757-1857 project, this case study will focus on a specific ceramic ware pattern rather than a particular item associated with the East India Company (EIC). With particular attention to the contents of Dunham Massey, Greater Manchester, I focus here on the Willow Pattern, a type of blue and white ‘Chinese style’ design, which was created in 1790 at the Caughley Factory in Shropshire. The large-scale production of ceramic wares featuring the same design became possible only in the late eighteenth century after John Sadler and Guy Green patented their method of transfer printing for commercial use in 1756. Willow Pattern wares became increasingly popular in the early nineteenth century, allowing large groups of people access to this design. Despite imitating Chinese wares so that they recalled Chinese hard-stone porcelain body and cobalt blue decorations, these wares remained distinct from them, often attracting lower values and esteem. Although unfashionable now, they should not be merely dismissed as poor imitations by contemporary scholars, but rather need to be recognized for their complexities. To explore and reveal the contradictions and intricacies held within Willow Pattern wares, this case study asks two simple questions. First, what did Willow Pattern wares mean in nineteenth-century Britain? Second, did EIC families—who, as a group, enjoyed privileged access to Chinese porcelain—engage with these imitative wares and if so, how, why and what might their interactions reveal about the household objects? As other scholars have shown, EIC officials’ cultural understandings of China often developed from engagements with the materials they imported, as well as discussions of and visits to China.