Ming Dynasty Porcelain Plate Laura G

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

'A Mind to Copy': Inspired by Meissen

‘A Mind to Copy’: Inspired by Meissen Anton Gabszewicz Independent Ceramic Historian, London Figure 1. Sir Charles Hanbury Williams by John Giles Eccardt. 1746 (National Portrait Gallery, London.) 20 he association between Nicholas Sprimont, part owner of the Chelsea Porcelain Manufactory, Sir Everard Fawkener, private sec- retary to William Augustus, Duke of Cumberland, the second son of King George II, and Sir Charles Hanbury Williams, diplomat and Tsometime British Envoy to the Saxon Court at Dresden was one that had far-reaching effects on the development and history of the ceramic industry in England. The well-known and oft cited letter of 9th June 1751 from Han- bury Williams (fig. 1) to his friend Henry Fox at Holland House, Kensington, where his china was stored, sets the scene. Fawkener had asked Hanbury Williams ‘…to send over models for different Pieces from hence, in order to furnish the Undertakers with good designs... But I thought it better and cheaper for the manufacturers to give them leave to take away any of my china from Holland House, and to copy what they like.’ Thus allowing Fawkener ‘… and anybody He brings with him, to see my China & to take away such pieces as they have a mind to Copy.’ The result of this exchange of correspondence and Hanbury Williams’ generous offer led to an almost instant influx of Meissen designs at Chelsea, a tremendous impetus to the nascent porcelain industry that was to influ- ence the course of events across the industry in England. Just in taking a ca- sual look through the products of most English porcelain factories during Figure 2. -

Karbury's Auction House

Karbury's Auction House Antiques Estates & Collection Sale Saturday - September 8, 2018 Antiques Estates & Collection Sale 307: A Chinese Gilt Bronze Buddhist Figure USD 300 - 500 308: A Set of Four Bronze Cups USD 200 - 300 309: A Song Style Jizhou Tortoiseshell-Glazed Tea Bowl USD 1,000 - 2,000 310: A Bronze Snake Sculpture USD 100 - 200 311: A Wood Pillow with Bone Inlaid USD 100 - 200 312: A Carved Ink Stone USD 200 - 300 313: A Stone Carved Head of Buddha USD 100 - 200 314: A Doucai Chicken Cup with Yongzheng Mark USD 500 - 700 Bid Live Online at LiveAuctioneers.com Page 1 Antiques Estates & Collection Sale 315: A Jian Ware Tea Bowl in Silver Hare Fur Streak USD 800 - 1,500 316: A Celadon Glazed Double Gourd Vase USD 400 - 600 317: Three Porcelain Dog Figurines USD 200 - 400 318: A Jun ware flower Pot USD 1,500 - 2,000 319: A Pair of Famille Rose Jars with Cover USD 800 - 1,200 320: A Blanc-De-Chine Figure of Seated Guanyin USD 1,500 - 2,000 321: A Pair of Vintage Porcelain Lamps USD 200 - 300 322: A Chicken Head Spout Ewer USD 800 - 1,200 Bid Live Online at LiveAuctioneers.com Page 2 Antiques Estates & Collection Sale 323: Two sancai figures and a ceramic cat-motif pillow USD 200 - 300 324: A Teadust Glazed Vase with Qianlong Mark USD 500 - 800 325: A Rosewood Tabletop Curio Display Stand USD 300 - 500 326: A Blue and White Celadon Glazed Vase USD 300 - 500 327: A Wucai Dragon Jar with Cover USD 300 - 500 328: A Green and Aubergine-Enameled Yellow-Ground Vase USD 200 - 300 329: A Celadon Square Sectioned Dragon Vase USD 200 - 300 -

Modern, Elegant and Wonderfully Versatile

MODERN, ELEGANT AND WONDERFULLY VERSATILE. MEISSEN® COSMOPOLITAN CHANGES THE WAY WE THINK ABOUT DINING SERVICES. WWW.MEISSEN.COM 1 AM-000076 TABLEWARE MEISSEN® COSMOPOLITAN STAATLICHE PORZELLAN-MANUFAKTUR MEISSEN GMBH 2 3 ABOUT US Meissen Porcelain Manufactory Meissen porcelain was born out of passion. Augustus the Strong (1670- 1733), Elector of Saxony, zealously pursued the so-called white gold after becoming struck with “Maladie de Porcelaine.” It was for him that alchemist Johann Friedrich Böttger (1682-1719) created the first European porcelain in 1708. At MEISSEN, this storied passion remains the fundament of the manufactory’s masterful works up to this day. More than 300 years of tra- dition and exquisite craftsmanship, unbounded imagination and an avowed dedication to modernity come together to create a timeless aesthetic that can be lived and experienced – every piece handmade in Germany. In 1710, Augustus the Strong decreed the founding of the Meissen porce- lain manufactory, making it the oldest in Europe. The signet of two crossed swords has been the unmistakable trademark of Meissen porcelain since 1722. The swords represent the uncompromising quality, unsurpassed craftsmanship and cultural heritage to which MEISSEN remains committed to this day: from the purest raw material sourced from the manufactory’s own kaolin mine, the world’s largest and oldest trove of moulds, models, patterns and decorations spanning centuries of artistic epochs, to the 10,000 proprietary paint formulas created in the on-site laboratory. And last but not least, they stand for the unsurpassed handicraft, experience and dedication of the manufactory’s artisans, lending every Meissen piece its one-of-a-kind beauty. -

Fabrication Porcelain Slabs

BASIC RECOMMENDATIONS FOR FABRICATING WALKER ZANGER’S SECOLO PORCELAIN SLABS CNC Bridge Saw Cutting Parameters: • Make certain the porcelain slab is completely supported on the flat, level, stable, and thoroughly cleaned bridge saw cutting table. • Use a Segmented Blade - Diameter 400 mm @ 1600 RPM @ 36” /min. We recommend an ADI MTJ64002 - Suitable for straight and 45-degree cuts. • Adjust the water feed directly to where the blade contacts the slab. • Before the fabrication starts, it is important to trim 3/4” from the slab’s four edges to remove any possible stress tension that may be within the slab. (Figure 1 on next page) • Reduce feed rate to 18”/min for the first and last 7” for starting and finishing the cut over the full length of the slab being fabricated. (Figure 2 on next page) • For 45-degree edge cuts reduce feed rate to 24” /min. • Drill sink corners with a 3/8” core bit at 4500 RPM and depth 3/4” /min. • Cut a secondary center sink cut 3” inside the finish cut & remove that center piece first, followed by removing the four 3” strips just inside the new sink edge. (Figure 3 on next page) • Keep at least 2” of distance between the perimeter of the cut-out and the edge of the countertop. • Use Tenax Enhancer Ager to soften the white vertical porcelain edge for under mount sink applications. • For Statuary, Calacata Gold, and Calacata Classic slabs bond mitered edge detail with Tenax Powewrbond in the color Paper White. (Interior & Exterior Applications - Two week lead time) • Some applications may require a supporting backer board material to be adhered to the backs of the slabs. -

PORCELAIN TILE PORCELAIN TILE INDEX Moodboard .02 Color Palette .03 Colors & Sizes

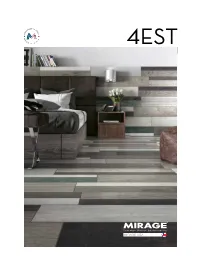

PORCELAIN TILE PORCELAIN TILE INDEX moodboard .02 color palette .03 colors & sizes . 1 8 sizes, finishes and packaging .22 field tile application areas .23 tile performance data .23 theconcept COLLECTION With its unique style, 4est offers an original take on wood: a mix of colors and graphic patterns that move away from the traditional canons of beauty, for a modern, eye-catching mash-up. A porcelain stoneware collection with excellent technical performance, where natural and recycled wood blend together into a mood with a raw yet supremely contemporary flavor, giving rise to intense patterns and colors. 4EST collection is designed in Italy and manufactured in USA Photographed samples are intended to give an approximate idea of the product. Colors and textures shown are not binding and may vary from actual products. Samples can be ordered from Mirage U.S.A. website: www.mirageusa.net/samples inspiredMOODBOARD by paletteCOLOR Available in both warm and cold shades, is embodied by the Curry and Indigo the combination of colors with wood nuances, offering a variety of style options. 2 | | 3 curry ET01 indigo ET02 Photographed samples are intended to give an approximate idea of the product. Colors and textures shown are not binding and may vary from actual products. 4 | curry | 5 FLOOR: curry ET01 8”x40” NAT NOT RECT WALL: scraped HM20 Brick 3”x12” NAT NOT RECT 6 | | 7 curry FLOOR: curry ET01 8”x40” NAT NOT RECT WALL: scraped HM20 Brick 3”x12” NAT NOT RECT 8 | | 9 indigo FLOOR: indigo ET02 8”x40” NAT NOT RECT WALL: maioliche light taupe HM -

Ford Ceramic Arts Columbus, Ohio

The Journal of the American Art Pottery Association, v.14, n. 2, p. 12-14, 1998. © American Art Pottery Association. http://www.aapa.info/Home/tabid/120/Default.aspx http://www.aapa.info/Journal/tabid/56/Default.aspx ISSN: 1098-8920 Ford Ceramic Arts Columbus, Ohio By James L. Murphy For about five years during the late 1930s, the combination of inventive and artistic talent pro- vided by Walter D. Ford (1906-1988) and Paul V. Bogatay (1905-1972), gave life to Ford Ceramic Arts, Inc., a small and little-known Columbus, Ohio, firm specializing in ceramic art and design. The venture, at least in the beginning, was intimately associated with Ohio State University (OSU), from which Ford graduated in 1930 with a degree in Ceramic Engineering, and where Bogatay began his tenure as an instructor of design in 1934. In fact, the first plant, begun in 1936, was actually located on the OSU campus, at 319 West Tenth Avenue, now the site of Ohio State University’s School of Nursing. There two periodic kilns produced “decorated pottery and dinnerware, molded porcelain cameos, and advertising specialties.” Ford was president and ceramic engineer; Norman M. Sullivan, secretary, treasurer, and purchasing agent; Bogatay, art director. Subsequently, the company moved to 4591 North High Street, and Ford's brother, Byron E., became vice-president. Walter, or “Flivver” Ford, as he had been known since high school, was interested primarily in the engineering aspects of the venture, and it was several of his processes for producing photographic images in relief or intaglio on ceramics that distinguished the products of the company. -

1 the Willow Pattern

The East India Company at Home, 1757-1857 – UCL History The Willow Pattern: Dunham Massey By Francesca D’Antonio Please note that this case study was first published on blogs.ucl.ac.uk/eicah in June 2014. For citation advice, visit: http://blogs.uc.ac.uk/eicah/usingthewebsite. Unlike other ‘objects studies’ featured in the East India Company At Home 1757-1857 project, this case study will focus on a specific ceramic ware pattern rather than a particular item associated with the East India Company (EIC). With particular attention to the contents of Dunham Massey, Greater Manchester, I focus here on the Willow Pattern, a type of blue and white ‘Chinese style’ design, which was created in 1790 at the Caughley Factory in Shropshire. The large-scale production of ceramic wares featuring the same design became possible only in the late eighteenth century after John Sadler and Guy Green patented their method of transfer printing for commercial use in 1756. Willow Pattern wares became increasingly popular in the early nineteenth century, allowing large groups of people access to this design. Despite imitating Chinese wares so that they recalled Chinese hard-stone porcelain body and cobalt blue decorations, these wares remained distinct from them, often attracting lower values and esteem. Although unfashionable now, they should not be merely dismissed as poor imitations by contemporary scholars, but rather need to be recognized for their complexities. To explore and reveal the contradictions and intricacies held within Willow Pattern wares, this case study asks two simple questions. First, what did Willow Pattern wares mean in nineteenth-century Britain? Second, did EIC families—who, as a group, enjoyed privileged access to Chinese porcelain—engage with these imitative wares and if so, how, why and what might their interactions reveal about the household objects? As other scholars have shown, EIC officials’ cultural understandings of China often developed from engagements with the materials they imported, as well as discussions of and visits to China. -

China: Qing Dynasty Porcelain and Global Exchange Pre-Visit

China: Qing Dynasty Porcelain and Global Exchange Pre-Visit Share this background information with students before your Distance Learning session. Grade Level: Grades 9-12 Collection: East Asian Art Culture/Region: China, East Asia Subject Area: History and Social Science Activity Type: Distance Learning WHY LOOK AT PLATES AND VASES? When visiting a relative or a fancy restaurant, perhaps you have dined on “fine china.” While today we appreciate porcelain dinnerware for the refinement it can add to an occasion, this conception is founded on centuries of exchange between Asian and Western markets. Chinese porcelain production has a long history of experimentation, innovation, and inspiration resulting in remarkably beautiful examples of form and imagery. At the VMFA, you will examine objects from a small portion of this history — the 18th century during the Qing Dynasty — to expand your understanding of global exchange in this era. Because they were made for trade outside of China, these objects are categorized as export porcelain by collectors and art historians. Review the background information below, and think of a few answers you want to look for when you visit VMFA. QING DYNASTY Emperors, Arts, and Trade Around the end of the 16th century, a Jurchin leader named Nurhaci (1559–1626) brought together various nomadic groups who became known as the Manchus. His forces quickly conquered the area of present-day Manchuria, and his heirs set their sights on China. In 1636 the Manchus chose the new name of Qing, meaning “pure,” to emphasize their intention to purify China by seizing power from the Ming dynasty. -

Page 1 578 a Japanese Porcelain Polychrome Kendi, Kutani, 17Th C

Ordre Designation Estimation Estimation basse haute 551 A Chinese mythological bronze group, 19/20th C. H: 28 cm 250 350 552 A Chinese bronze elongated bottle-shaped vase, Ming Dynasty H.: 31 600 1200 cm 553 A partial gilt seated bronze buddha, Yongzheng mark, 19th C. or earlier 800 1200 H: 39 cm L: 40 cm Condition: good. The gold paint somewhat worn. 554 A Chinese bronze jardiniere on wooden stand, 19/20th C. H.: 32 cm 300 600 555 A Chinese figural bronze incense burner, 17/18th C. H.: 29 cm 1000 1500 556 A Chinese bronze and cloisonne figure of an immortal, 18/19th C. H.: 31 300 600 cm 557 A Chinese bronze figure of an emperor on a throne, 18/19th C. H.: 30 cm 800 1200 Condition: missing a foot on the right bottom side. 558 A bronze figure of Samanthabadra, inlaid with semi-precious stones, 4000 8000 Ming Dynasty H: 28 cm 559 A Chinese gilt bronze seated buddha and a bronze Tara, 18/19th C. H.: 600 1200 14 cm (the tallest) 560 A Chinese bronze tripod incense burner with trigrams, 18/19th C. H.: 350 700 22,3 cm 561 A tall pair of Chinese bronze “Luduan� figures, 18/19th C. H.: 29 1200 1800 cm 562 A tall gilt bronze head of a Boddhisatva with semi-precious stones, Tibet, 1000 1500 17/18th C. H.: 33 cm 563 A dark bronze animal subject group, China, Ming Dynasty, 15-16th C. H.: 1500 2500 25,5 cm 564 A Chinese dragon censer in champlevé enameled bronze, 18/19th C. -

Cincinnati Art Asian Society Virtual November 2020: Asian Ceramics

Cincinnati Art Asian Society Virtual November 2020: Asian Ceramics Though we can't meet in person during the pandemic, we still want to stay connected with you through these online resources that will feed our mutual interest in Asian arts and culture. Until we can meet again, please stay safe and healthy. Essays: East and West: Chinese Export Porcelain https://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/ewpor/hd_ewpor.htm Introduced to Europe in the fourteenth century, Chinese porcelains were regarded as objects of great rarity and luxury. Through twelve examples you’ll see luxury porcelains that appeared in Europe in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries, often mounted in gilt silver, which emphasized their preciousness and transformed them into entirely different objects. The Vibrant Role of Mingqui in Early Chinese Burials https://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/mgqi/hd_mgqi.htm Burial figurines of graceful dancers, mystical beasts, and everyday objects reveal both how people in early China approached death and how they lived. Since people viewed the afterlife as an extension of worldly life, these ceramic figurines, called mingqi or “spirit goods,” disclose details of routine existence and provide insights into belief systems over a thousand-year period. Mingqi were popularized during the formative Han dynasty (206 B.C.–220 A.D.) and endured through the turbulent Six Dynasties period (220–589) and the later reunification of China in the Sui (581–618) and Tang (618–907) dynasties. There are eleven ceramic burial goods (and one limestone) as great examples of mingqui. Indian Pottery https://www.veniceclayartists.com/tag/indian-pottery/ The essay is informative but short. -

Chinese Art the Szekeres Collection

Chinese Art The Szekeres Collection J. J. Lally & Co. oriental art Chinese Art The Szekeres Collection Chinese Art The Szekeres Collection March 13 to 29, 2019 J. J. Lally & Co. oriental art 41 East 57th Street New York, NY 10022 Tel (212) 371-3380 Fax (212) 593-4699 e-mail [email protected] www.jjlally.com Janos Szekeres ANOS Szekeres was a scientist, an When his success in business gave him greater resources for collecting art, he first inventor, an aviator, a businessman and a formed a collection of Post-Impressionist paintings, which he had always loved, but Jfamily man. The outline of his life reads as business affairs brought him back to Asia he once again began to visit the antiques like a classic American success story. Born in shops looking for Chinese art, and soon he had a significant collection of Chinese snuff Hungary in 1914, Janos attended the University bottles. His interest and sophistication grew rapidly and eventually he served on the of Vienna for his graduate studies in chemistry. Board of Directors of the International Chinese Snuff Bottle Society and on the Chinese When war in Europe was imminent he signed Art Collections Committee of the Harvard University Art Museums. A trip to China in on as a seaman on a commercial freighter and, 1982 visiting Chinese art museums, kiln sites and monuments reinforced a wider interest on arrival in New York harbor, “jumped ship.” in Chinese ceramics and works of art. He enlisted in the US Army Air Force in 1941 Janos took great pleasure in collecting. -

Fourteenth-Century Blue-And-White : a Group of Chinese Porcelains in the Topkapu Sarayi Müzesi, Istanbul

SMITHSONIAN INSTITUTION! FREER GALLERY OF ART OCCASIONAL PAPERS VOLUME TWO NUMBER ONE FOURTEENTH-CENTURY BLUE-AND-WHITE A GROUP OF CHINESE PORCELAINS IN THE TOPKAPU SARAYI MUZESI, ISTANBUL By JOHN ALEXANDER POPE WASHINGTON 1952 FREER GALLERY OF ART OCCASIONAL PAPERS The Freer Gallery of Art Occasional Papers, published from time to time, present material pertaining to the cultures represented in the Freer Collection, prepared by members of the Gallery staff. Articles dealing with objects in the Freer Collection and involving original research in Near Eastern or Far Eastern language sources by scholars not associated with the Gallery may be considered for publication. The Freer Gallery of Art Occasional Papers are not sold by subscrip- tion. The price of each number is determined with reference to the cost of publication. = SMITHSONI AN INSTITUTIONS FREER GALLERY OF ART OCCASIONAL PAPERS VOLUME TWO NUMBER ONE FOURTEENTH-CENTURY BLUE-AND-WHITE A GROUP OF CHINESE PORCELAINS IN THE TOPKAPU SARAYI MUZESI, ISTANBUL - By JOHN ALEXANDER POPE Publication 4089 WASHINGTON 1952 BALTIMORE, MS., XT. S. A. CONTENTS Page Introduction 1 The background 1 Acknowledgments 4 Numerical list = 6 Chronological data 7 The Topkapu Sarayi Collection 8 History 8 Scope 18 The early blue-and-white wares 24 The painter's repertory 30 Flora 33 Fauna 40 Miscellaneous 44 Description of plates A-D 49 The argument 50 Descriptions of the pieces as illustrated 53 Appendix I: Checklist 66 II: Locale 69 III : Zimmermann's attributions 72 Bibliography 74 Index 79 iii FOURTEENTH-CENTURY BLUE-AND- WHITE: A GROUP OF CHINESE PORCELAINS IN THE TOPKAPU SARAYI MiiZESI, ISTANBUL By JOHN ALEXANDER POPE Assistant Director, Freer Gallery of Art [With 44 Plates] INTRODUCTION THE BACKGROUND Attempts to assign pre-Ming dates to Chinese porcelains decorated in underglaze cobalt blue are by no means new, but they have never ceased to be troublesome; certainly no general agreement in the matter has been reached beyond the fact that such porcelains do exist.