Porcelain Tableware

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

'A Mind to Copy': Inspired by Meissen

‘A Mind to Copy’: Inspired by Meissen Anton Gabszewicz Independent Ceramic Historian, London Figure 1. Sir Charles Hanbury Williams by John Giles Eccardt. 1746 (National Portrait Gallery, London.) 20 he association between Nicholas Sprimont, part owner of the Chelsea Porcelain Manufactory, Sir Everard Fawkener, private sec- retary to William Augustus, Duke of Cumberland, the second son of King George II, and Sir Charles Hanbury Williams, diplomat and Tsometime British Envoy to the Saxon Court at Dresden was one that had far-reaching effects on the development and history of the ceramic industry in England. The well-known and oft cited letter of 9th June 1751 from Han- bury Williams (fig. 1) to his friend Henry Fox at Holland House, Kensington, where his china was stored, sets the scene. Fawkener had asked Hanbury Williams ‘…to send over models for different Pieces from hence, in order to furnish the Undertakers with good designs... But I thought it better and cheaper for the manufacturers to give them leave to take away any of my china from Holland House, and to copy what they like.’ Thus allowing Fawkener ‘… and anybody He brings with him, to see my China & to take away such pieces as they have a mind to Copy.’ The result of this exchange of correspondence and Hanbury Williams’ generous offer led to an almost instant influx of Meissen designs at Chelsea, a tremendous impetus to the nascent porcelain industry that was to influ- ence the course of events across the industry in England. Just in taking a ca- sual look through the products of most English porcelain factories during Figure 2. -

Fabrication Porcelain Slabs

BASIC RECOMMENDATIONS FOR FABRICATING WALKER ZANGER’S SECOLO PORCELAIN SLABS CNC Bridge Saw Cutting Parameters: • Make certain the porcelain slab is completely supported on the flat, level, stable, and thoroughly cleaned bridge saw cutting table. • Use a Segmented Blade - Diameter 400 mm @ 1600 RPM @ 36” /min. We recommend an ADI MTJ64002 - Suitable for straight and 45-degree cuts. • Adjust the water feed directly to where the blade contacts the slab. • Before the fabrication starts, it is important to trim 3/4” from the slab’s four edges to remove any possible stress tension that may be within the slab. (Figure 1 on next page) • Reduce feed rate to 18”/min for the first and last 7” for starting and finishing the cut over the full length of the slab being fabricated. (Figure 2 on next page) • For 45-degree edge cuts reduce feed rate to 24” /min. • Drill sink corners with a 3/8” core bit at 4500 RPM and depth 3/4” /min. • Cut a secondary center sink cut 3” inside the finish cut & remove that center piece first, followed by removing the four 3” strips just inside the new sink edge. (Figure 3 on next page) • Keep at least 2” of distance between the perimeter of the cut-out and the edge of the countertop. • Use Tenax Enhancer Ager to soften the white vertical porcelain edge for under mount sink applications. • For Statuary, Calacata Gold, and Calacata Classic slabs bond mitered edge detail with Tenax Powewrbond in the color Paper White. (Interior & Exterior Applications - Two week lead time) • Some applications may require a supporting backer board material to be adhered to the backs of the slabs. -

Ming Dynasty Porcelain Plate Laura G

Wonders of Nature and Artifice Art and Art History Fall 2017 Blue-and-White Wonder: Ming Dynasty Porcelain Plate Laura G. Waters '19, Gettysburg College Follow this and additional works at: https://cupola.gettysburg.edu/wonders_exhibit Part of the Ancient, Medieval, Renaissance and Baroque Art and Architecture Commons, Fine Arts Commons, History of Science, Technology, and Medicine Commons, Industrial and Product Design Commons, and the Intellectual History Commons Share feedback about the accessibility of this item. Waters, Laura G., "Blue-and-White Wonder: Ming Dynasty Porcelain Plate" (2017). Wonders of Nature and Artifice. 12. https://cupola.gettysburg.edu/wonders_exhibit/12 This is the author's version of the work. This publication appears in Gettysburg College's institutional repository by permission of the copyright owner for personal use, not for redistribution. Cupola permanent link: https://cupola.gettysburg.edu/wonders_exhibit/12 This open access student research paper is brought to you by The uC pola: Scholarship at Gettysburg College. It has been accepted for inclusion by an authorized administrator of The uC pola. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Blue-and-White Wonder: Ming Dynasty Porcelain Plate Abstract This authentic Ming Dynasty (1368-1644) plate is a prime example of early export porcelain, a luminous substance that enthralled European collectors. The eg nerous gift of oJ yce P. Bishop in honor of her daughter, Kimberly Bishop Connors, Ming Dynasty Blue-and-White Plate is on loan from the Reeves Collection at Washington and Lee University in Lexington, Virginia. The lp ate itself is approximately 7.75 inches (20 cm) in diameter, and appears much deeper from the bottom than it does from the top. -

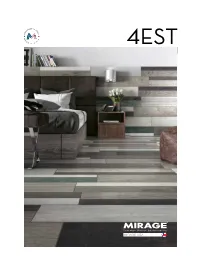

PORCELAIN TILE PORCELAIN TILE INDEX Moodboard .02 Color Palette .03 Colors & Sizes

PORCELAIN TILE PORCELAIN TILE INDEX moodboard .02 color palette .03 colors & sizes . 1 8 sizes, finishes and packaging .22 field tile application areas .23 tile performance data .23 theconcept COLLECTION With its unique style, 4est offers an original take on wood: a mix of colors and graphic patterns that move away from the traditional canons of beauty, for a modern, eye-catching mash-up. A porcelain stoneware collection with excellent technical performance, where natural and recycled wood blend together into a mood with a raw yet supremely contemporary flavor, giving rise to intense patterns and colors. 4EST collection is designed in Italy and manufactured in USA Photographed samples are intended to give an approximate idea of the product. Colors and textures shown are not binding and may vary from actual products. Samples can be ordered from Mirage U.S.A. website: www.mirageusa.net/samples inspiredMOODBOARD by paletteCOLOR Available in both warm and cold shades, is embodied by the Curry and Indigo the combination of colors with wood nuances, offering a variety of style options. 2 | | 3 curry ET01 indigo ET02 Photographed samples are intended to give an approximate idea of the product. Colors and textures shown are not binding and may vary from actual products. 4 | curry | 5 FLOOR: curry ET01 8”x40” NAT NOT RECT WALL: scraped HM20 Brick 3”x12” NAT NOT RECT 6 | | 7 curry FLOOR: curry ET01 8”x40” NAT NOT RECT WALL: scraped HM20 Brick 3”x12” NAT NOT RECT 8 | | 9 indigo FLOOR: indigo ET02 8”x40” NAT NOT RECT WALL: maioliche light taupe HM -

Ford Ceramic Arts Columbus, Ohio

The Journal of the American Art Pottery Association, v.14, n. 2, p. 12-14, 1998. © American Art Pottery Association. http://www.aapa.info/Home/tabid/120/Default.aspx http://www.aapa.info/Journal/tabid/56/Default.aspx ISSN: 1098-8920 Ford Ceramic Arts Columbus, Ohio By James L. Murphy For about five years during the late 1930s, the combination of inventive and artistic talent pro- vided by Walter D. Ford (1906-1988) and Paul V. Bogatay (1905-1972), gave life to Ford Ceramic Arts, Inc., a small and little-known Columbus, Ohio, firm specializing in ceramic art and design. The venture, at least in the beginning, was intimately associated with Ohio State University (OSU), from which Ford graduated in 1930 with a degree in Ceramic Engineering, and where Bogatay began his tenure as an instructor of design in 1934. In fact, the first plant, begun in 1936, was actually located on the OSU campus, at 319 West Tenth Avenue, now the site of Ohio State University’s School of Nursing. There two periodic kilns produced “decorated pottery and dinnerware, molded porcelain cameos, and advertising specialties.” Ford was president and ceramic engineer; Norman M. Sullivan, secretary, treasurer, and purchasing agent; Bogatay, art director. Subsequently, the company moved to 4591 North High Street, and Ford's brother, Byron E., became vice-president. Walter, or “Flivver” Ford, as he had been known since high school, was interested primarily in the engineering aspects of the venture, and it was several of his processes for producing photographic images in relief or intaglio on ceramics that distinguished the products of the company. -

China: Qing Dynasty Porcelain and Global Exchange Pre-Visit

China: Qing Dynasty Porcelain and Global Exchange Pre-Visit Share this background information with students before your Distance Learning session. Grade Level: Grades 9-12 Collection: East Asian Art Culture/Region: China, East Asia Subject Area: History and Social Science Activity Type: Distance Learning WHY LOOK AT PLATES AND VASES? When visiting a relative or a fancy restaurant, perhaps you have dined on “fine china.” While today we appreciate porcelain dinnerware for the refinement it can add to an occasion, this conception is founded on centuries of exchange between Asian and Western markets. Chinese porcelain production has a long history of experimentation, innovation, and inspiration resulting in remarkably beautiful examples of form and imagery. At the VMFA, you will examine objects from a small portion of this history — the 18th century during the Qing Dynasty — to expand your understanding of global exchange in this era. Because they were made for trade outside of China, these objects are categorized as export porcelain by collectors and art historians. Review the background information below, and think of a few answers you want to look for when you visit VMFA. QING DYNASTY Emperors, Arts, and Trade Around the end of the 16th century, a Jurchin leader named Nurhaci (1559–1626) brought together various nomadic groups who became known as the Manchus. His forces quickly conquered the area of present-day Manchuria, and his heirs set their sights on China. In 1636 the Manchus chose the new name of Qing, meaning “pure,” to emphasize their intention to purify China by seizing power from the Ming dynasty. -

64997 Frontier Loriann

[ FRESH TAKE ] Thrown for a Loop factory near his Staffordshire hometown, Stoke-on-Trent. Wedgwood married traditional craftsmanship with A RESILIENT POTTERY COMPANY FACES progressive business practices and contemporary design. TRYING TIMES He employed leading artists, including the sculptor John Flaxman, whose Shield of Achilles is in the Huntington by Kimberly Chrisman-Campbell collection, along with his Wedgwood vase depicting Ulysses at the table of Circe. As sturdy as they were beautiful, Wedgwood products made high-quality earthenware available to the middle classes. his past winter, Waterford Wedgwood found itself teetering on the edge of bankruptcy like a ceramic vase poised to topple from its shelf. As the company struggles A mainstay of bridal registries, the distinctive for survival, visitors to The Tearthenware is equally at home in museums around the world, including The Huntington. Now owned by an Irish firm, the once-venerable pottery manufactory was founded Huntington can appreciate by Englishman Josiah Wedgwood in 1759. As the company struggles for survival, visitors to The Huntington can appre - what a great loss its demise ciate what a great loss its demise would be. A look at the firm’s history reveals that the current crisis is just the most recent would be. of several that Wedgwood has overcome in its 250 years. The story of Wedgwood is one of the great personal and Today, Wedgwood is virtually synonymous with professional triumphs of the 18th century. Born in 1730 into Jasperware, an unglazed vitreous stoneware produced from a family of potters, Josiah Wedgwood started working at the barium sulphate. It is usually pale blue, with separately age of nine as a thrower, a craftsman who shaped pottery on molded white reliefs in the neoclassical style. -

Painting with Overglazes

There is nothing more difficult for a truly creative painter than to paint 5 a rose, because before he can do so he has to first forget all the roses that were Chapter ever painted. —Henri Matisse (1869–1954) Painting with Overglazes Many artists come to china painting with extensive experience in other art forms, particularly oil and watercolor painting. A few come from a ceramic background, seeking a more painterly approach. MOverglazing is a special art form in several ways, and occupies a distinctive niche in the con- tinuum from painting to glazing. Painters will enjoy the depth, luminosity, and permanence of china painting. Potters will delight in a medium that is more like painting than any other ceramic technique, and offers a full range of colors. Both groups will appreciate the fact that the raw colors are almost identical to the fired colors. What makes china painting truly unique is its application onto a glossy surface. This creates spe- cial challenges, but also special possibilities. The material is a powder suspended in a medium, and as such, is adaptable to any of the techniques used with any form of paint or ink. It may even be used dry, like metal enamels. As in all art forms, there is no right or wrong way to use china paint. There are only those meth- ods that work for you. What to Paint On Any fired ceramic object may be decorated with china paint. Whether it’s high- or low-fired, glazed or unglazed, you can china paint it some- how. -

February 16 ROYAL CROWN DERBY CELEBRATES 90 GLORIOUS YEARS of QUEEN ELIZABETH II

February 16 ROYAL CROWN DERBY CELEBRATES 90 GLORIOUS YEARS OF QUEEN ELIZABETH II As the British Monarchy prepare to celebrate the 90th birthday of Queen Elizabeth II (Thursday 21st April 2016) fine bone china perfectionist, Royal Crown Derby is marking this momentous occasion with a beautifully handcrafted commemorative collection, designed by renowned royal specialist, June Branscombe. Hand-crafted in England by Royal Crown Derby’s skilled artisans, in its historic Osmaston Road factory, the collection, which will be available to purchase in April, features five delicate pieces; a 21.5cm Talbot Plate, Loving Cup, Miniature Loving Cup, Covered Trinket Box and Five Petal Tray, each festooned in rich blues and reds and hand-finished in 22-carat gold. Each item features a commemorative backstamp and will be a limited edition of 426 pieces (with the exception of the general release Five Petal Tray), to reflect the fourth month of 1926, when Queen Elizabeth was born. June Branscombe’s inspired designs follow the theme of the family badge of the House of Windsor - the Oak tree - and depicts the sovereign’s crown surrounded by the emblems of the United Kingdom; the Tudor rose of England, the thistle of Scotland, the leek of Wales and the shamrock of Northern Ireland. The centre of the plate carries the Queen’s Cipher – E II R with the Sovereign’s Crown within a cartouche of oak leaves and all items are surrounded by a commemorative inscription, “To Celebrate the Ninetieth Birthday of H.M. Queen Elizabeth II 21st April 2016”, making each item the perfect addition to any royal aficionado’s collection. -

The Introduction of Celadon Production in North China: Technological Characteristics and Diversity of the Earliest Wares

The Introduction of Celadon Production in North China: Technological Characteristics and Diversity of the Earliest Wares Shan Huang*1, Ian C. Freestone1, Yanshi Zhu2, Lihua Shen2 * Corresponding Author: [email protected] 1 Institute of Archaeology, University College London, 31-34 Gordon Square, WC1H 0PY, London, UK 2 Institute of Archaeology, Chinese Academy of Social Sciences, 27 Wangfujing Avenue, 100710, Beijing, China Abstract Celadon, technically a stoneware with a lime-rich glaze, had been produced in South China for more than two millennia before it was first made in the North in the second half of the sixth century. It appears to have been an immediate precursor to white porcelain, which was first produced by northern kilns. The compositions and microstructures of early northern celadons from kilns, residential sites and tombs in Shandong, Hebei and Henan provinces, and dated 550s-618 CE, have been determined by SEM-EDS. The majority of the vessels were made using a low-iron kaolinitic clay, with high alumina (20-29%), as anticipated for northern clays. A small number of celadon vessels from a kiln at Caocun, which produced mainly lead-glazed wares, have lower alumina contents and appear to have originated in the South. It seems possible that these imported vessels were being used by the potters as models on which Caocun wares were based. Consistent differences in major element composition are observed between the products of kilns at Anyang, Xing, Luoyang and Zhaili. Unlike southern celadon glazes, which were prepared as two-component mixtures of vegetal ash and body clay, the northern celadon glazes are three-component, and typically contained an additional siliceous component, probably loess. -

General Condition Terms for Ceramics the Purpose of This Glossary Is To

General Condition terms for Ceramics The purpose of this glossary is to provide you with a common language for the condition of ceramic items. Hardness the hardness of a ceramic is dependent on the type of clay used, its porosity and firing temperature. The following are simples classifications. Greenware Unfired clay articles. Earthenware- A glazed porous ceramic created by low temperature firing. Majolica or maiolica is tin glazed earthenware and overpainted with oxides developed in Majorca. Similar pottery is known in France as Faience and the UK as Deftware. Porcelain- Kaolin based ceramic body that has been fired between 1200oC- 1400°C vitrifying the composition becoming non porous Bisque-unglazed porcelain Flaws Flaws are defects, visible marks or inclusions made during the manufacturing process that should be included in the description. Damage Damage describes defects made through use, handling, cleaning or storage. Damage includes nicks, cracks, scratches, paint wear and crazing. Abrasion – Scuff marks or areas of concentrated scratches, generally caused by rubbing against another item over time. Accretions-build up or deposit of a foreign materials on a surface Efflorescence-white powdery or hard salt deposits that are located on the surface of the ceramic Spalling- loss from the separation of the ceramic layers due salts migrating through the body and glaze Flaking –lifting and separation of the glazing from the ceramic body without complete loss of the insecure area Light scratches - Scratches which do not score the surface of the item. Can be seen but not felt. Deep scratches - Scratches which score the surface of the item and can be felt with a fingernail. -

A Technological Combination of Lead-Glaze And

RESEARCH ARTICLE A technological combination of lead-glaze and calcium-glaze recently found in China: Scientific comparative analysis of glazed ceramics from Shangyu, Zhejiang Province Yue Wang, Yihang Zhou, Zhefeng Yang, Jianfeng CuiID* School of Archaeology and Museology, Peking University, Beijing, China a1111111111 a1111111111 * [email protected] a1111111111 a1111111111 a1111111111 Abstract To study the relationship between the glazed pottery from southern China and the lead- glazed pottery in northern China in the Han Dynasty (202BC-220AD), 34 samples unearthed OPEN ACCESS from Shangyu(上虞), Zhejiang Province have been studied by LA-ICP-AES, SEM/EDS and XRD. The results showed that these samples included the typical lead-glazed pottery, the Citation: Wang Y, Zhou Y, Yang Z, Cui J (2019) A technological combination of lead-glaze and proto-porcelain and the glazed pottery using both lead and calcium as glaze fluxing agents. calcium-glaze recently found in China: Scientific Previously, the lead-glazed pottery type was considered as the main northern products dur- comparative analysis of glazed ceramics from ing the Han dynasty while the calcium-glazed pottery type or the proto-porcelain was the Shangyu, Zhejiang Province. PLoS ONE 14(7): representative of the south of China. However, apart from the two typical types above, a e0219608. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal. pone.0219608 new variety of glaze categorized as the calcium-lead glaze was discovered in the samples from Shangyu. This indicates that there were technology exchanges and amalgamation of Editor: Peter F. Biehl, University at Buffalo - The State University of New York, UNITED STATES lead-glaze and calcium-glaze between the south and the north during the Han Dynasty.