Chinese Pottery Traditions 19

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Multiplicity: Contemporary Ceramic Sculpture' Exhibition Catalog Anne M Giangiulio, University of Texas at El Paso

University of Texas at El Paso From the SelectedWorks of Anne M. Giangiulio 2006 'Multiplicity: Contemporary Ceramic Sculpture' Exhibition Catalog Anne M Giangiulio, University of Texas at El Paso Available at: https://works.bepress.com/anne_giangiulio/32/ Contemporary Ceramic Sculpture Organized by the Stanlee and Gerald Rubin Center for the Visual Arts at the University of Texas at El Paso This publication accompanies the exhibition Multiplicity: Contemporary Ceramic Sculpture which was organized by the Stanlee and Gerald Rubin Center for the Visual Arts at the University of Texas at El Paso and co-curated by Kate Bonansinga and Vincent Burke. Published by The University of Texas at El Paso El Paso, TX 79968 www.utep.edu/arts Copyright 2006 by the authors, the artists and the University of Texas at El Paso. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced in any manner without permission from the University of Texas at El Paso. Exhibition Itinerary Portland Art Center Portland, OR March 2-April 22, 2006 Stanlee and Gerald Rubin Center for the Visual Arts Contemporary Ceramic Sculpture The University of Texas at El Paso El Paso, TX June 29-September 23, 2006 San Angelo Museum of Fine Arts San Angelo, TX April 20-June 24, 2007 Landmark Arts Texas Tech University Lubbock, TX July 6-August 17, 2007 Southwest School of Art and Craft San Antonio, TX September 6-November 7, 2007 The exhibition and its associated programming in El Paso have been generously supported in part by the Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts and the Texas Commission on the Arts. -

'A Mind to Copy': Inspired by Meissen

‘A Mind to Copy’: Inspired by Meissen Anton Gabszewicz Independent Ceramic Historian, London Figure 1. Sir Charles Hanbury Williams by John Giles Eccardt. 1746 (National Portrait Gallery, London.) 20 he association between Nicholas Sprimont, part owner of the Chelsea Porcelain Manufactory, Sir Everard Fawkener, private sec- retary to William Augustus, Duke of Cumberland, the second son of King George II, and Sir Charles Hanbury Williams, diplomat and Tsometime British Envoy to the Saxon Court at Dresden was one that had far-reaching effects on the development and history of the ceramic industry in England. The well-known and oft cited letter of 9th June 1751 from Han- bury Williams (fig. 1) to his friend Henry Fox at Holland House, Kensington, where his china was stored, sets the scene. Fawkener had asked Hanbury Williams ‘…to send over models for different Pieces from hence, in order to furnish the Undertakers with good designs... But I thought it better and cheaper for the manufacturers to give them leave to take away any of my china from Holland House, and to copy what they like.’ Thus allowing Fawkener ‘… and anybody He brings with him, to see my China & to take away such pieces as they have a mind to Copy.’ The result of this exchange of correspondence and Hanbury Williams’ generous offer led to an almost instant influx of Meissen designs at Chelsea, a tremendous impetus to the nascent porcelain industry that was to influ- ence the course of events across the industry in England. Just in taking a ca- sual look through the products of most English porcelain factories during Figure 2. -

Tactile Digital: an Exploration of Merging Ceramic Art and Industrial Design

INTERNATIONAL CONFERENCE ON ENGINEERING AND PRODUCT DESIGN EDUCATION 8 & 9 SEPTEMBER 2016, AALBORG UNIVERSITY, DENMARK TACTILE DIGITAL: AN EXPLORATION OF MERGING CERAMIC ART AND INDUSTRIAL DESIGN Dosun SHIN1 and Samuel CHUNG2 1Industrial Design, Arizona State University 2Ceramic Art, Arizona State University ABSTRACT This paper presents a pilot study that highlights collaboration between ceramic art and industrial design. The study is focused on developing a ceramic lamp that can be mass-produced and marketed as a design artefact. There are two ultimate goals of the study: first, to establish an iterative process of collaboration between ceramic art and industrial design through an example of manufactured design artefact and second to expand transdisciplinary and collaborative knowledge. Keywords: Trans-disciplinary collaboration, emerging design technology, ceramic art, industrial design. 1 INTRODUCTION The proposed project emphasizes collaboration between disciplines of ceramic art and industrial design to create a ceramic lamp that can be mass-produced and marketed as a design artefact. It addresses issues related to disciplinary challenges involved in the process and use of prototyping techniques that make this project unique. There are two ultimate goals of the project. First is to establish an iterative process of collaboration between ceramic art and industrial design through an example of manufactured 3D ceramic lamp. The second goal is to develop a transdisciplinary ceramic design course for Arizona State University students. The eventual intent is also to share generated knowledge with scholars from academia and industry through various conferences, academic, and technical platforms. In the following, we will first discuss theoretical perspectives about collaboration between ceramic art and industrial design to highlight positives and negatives of disciplinary associations. -

Fabrication Porcelain Slabs

BASIC RECOMMENDATIONS FOR FABRICATING WALKER ZANGER’S SECOLO PORCELAIN SLABS CNC Bridge Saw Cutting Parameters: • Make certain the porcelain slab is completely supported on the flat, level, stable, and thoroughly cleaned bridge saw cutting table. • Use a Segmented Blade - Diameter 400 mm @ 1600 RPM @ 36” /min. We recommend an ADI MTJ64002 - Suitable for straight and 45-degree cuts. • Adjust the water feed directly to where the blade contacts the slab. • Before the fabrication starts, it is important to trim 3/4” from the slab’s four edges to remove any possible stress tension that may be within the slab. (Figure 1 on next page) • Reduce feed rate to 18”/min for the first and last 7” for starting and finishing the cut over the full length of the slab being fabricated. (Figure 2 on next page) • For 45-degree edge cuts reduce feed rate to 24” /min. • Drill sink corners with a 3/8” core bit at 4500 RPM and depth 3/4” /min. • Cut a secondary center sink cut 3” inside the finish cut & remove that center piece first, followed by removing the four 3” strips just inside the new sink edge. (Figure 3 on next page) • Keep at least 2” of distance between the perimeter of the cut-out and the edge of the countertop. • Use Tenax Enhancer Ager to soften the white vertical porcelain edge for under mount sink applications. • For Statuary, Calacata Gold, and Calacata Classic slabs bond mitered edge detail with Tenax Powewrbond in the color Paper White. (Interior & Exterior Applications - Two week lead time) • Some applications may require a supporting backer board material to be adhered to the backs of the slabs. -

9. Ceramic Arts

Profile No.: 38 NIC Code: 23933 CEREMIC ARTS 1. INTRODUCTION: Ceramic art is art made from ceramic materials, including clay. It may take forms including art ware, tile, figurines, sculpture, and tableware. Ceramic art is one of the arts, particularly the visual arts. Of these, it is one of the plastic arts. While some ceramics are considered fine art, some are considered to be decorative, industrial or applied art objects. Ceramics may also be considered artifacts in archaeology. Ceramic art can be made by one person or by a group of people. In a pottery or ceramic factory, a group of people design, manufacture and decorate the art ware. Products from a pottery are sometimes referred to as "art pottery".[1] In a one-person pottery studio, ceramists or potters produce studio pottery. Most traditional ceramic products were made from clay (or clay mixed with other materials), shaped and subjected to heat, and tableware and decorative ceramics are generally still made this way. In modern ceramic engineering usage, ceramics is the art and science of making objects from inorganic, non-metallic materials by the action of heat. It excludes glass and mosaic made from glass tesserae. There is a long history of ceramic art in almost all developed cultures, and often ceramic objects are all the artistic evidence left from vanished cultures. Elements of ceramic art, upon which different degrees of emphasis have been placed at different times, are the shape of the object, its decoration by painting, carving and other methods, and the glazing found on most ceramics. 2. -

Cambridge University Press 978-1-108-49995-8 — the City of Blue and White Anne Gerritsen Index More Information

Cambridge University Press 978-1-108-49995-8 — The City of Blue and White Anne Gerritsen Index More Information 321 Index Note: Page numbers in bold refer to fi gures, and those in italics refer to maps. Abbasid Caliphate (750–1258), trade in, 1 – 2 introduction of, 15 Abu- Lughod, Janet, 44 – 46 , 45 , 47 , 55 Jingdezhen emergence of, 61 , 68 Ackerman- Lieberman, Phillip, 59 Jingdezhen global production of, 5 Africa, porcelain trade in, 59 in Joseon Korea, 125 , 125 , 126 animal patterns, 198 Kessler on dating of, 64 in Jizhou ceramics, 82 – 83 , 93 – 94 , 95 Linjiang kilns and, 102 – 103 see also deer ; dragon in ritual texts, 127 – 128 archaeologists, on porcelains, 6 , 117 in shard market, 3 – 5 , 16 , 1 7 archaeology, 6 , 12 – 13 , 34 , 52 , 82 – 83 , 106 underglaze painting of, 67 Cizhou ware ceramics, 32 – 33 Yu a n d y n a s t y a n d , 6 6 Ding ware ceramics, 24 , 32 – 33 bluish- white glaze, of qingbai ceramics, 40 Fengzhuang storehouse, 21 – 22 ‘Book of Ceramics’, see Taoshu hoards, 72 bottle Hutian kilns, 49 , 264n54 gourd- shaped, 196 – 197 , 196 , 198 , 214 Jizhou ware, 93 , 97 in shard market, 3 – 5 Linjiang kiln site, 102 – 103 tall- necked porcelain, 198 , 199 , maritime, 12 – 13 , 52 – 55 , 127 – 128 204 – 205 , 215 qingbai ceramics, 52 bowl, 172 shard market, 1 , 16 , 1 7 fi sh, 228 – 230 S i n a n s h i p w r e c k , 5 2 – 5 5 glaze patterns for, 35 – 36 Western Xia dynasty, 51 Jizhou ceramics dated, 95 , 96 , 97 Yonghe kilns, 76 , 77 w i t h luanbai glaze, 47 – 48 , 48 Ardabil collection, 205 in shard market, 3 – 5 art history, of porcelains, 6 see also tea bowls ‘Assorted Jottings of Shi Yushan’ Shi Yushan Brandt, George, 64 bieji (Shi Runzhang), 101 Brankston, A. -

Ming Dynasty Porcelain Plate Laura G

Wonders of Nature and Artifice Art and Art History Fall 2017 Blue-and-White Wonder: Ming Dynasty Porcelain Plate Laura G. Waters '19, Gettysburg College Follow this and additional works at: https://cupola.gettysburg.edu/wonders_exhibit Part of the Ancient, Medieval, Renaissance and Baroque Art and Architecture Commons, Fine Arts Commons, History of Science, Technology, and Medicine Commons, Industrial and Product Design Commons, and the Intellectual History Commons Share feedback about the accessibility of this item. Waters, Laura G., "Blue-and-White Wonder: Ming Dynasty Porcelain Plate" (2017). Wonders of Nature and Artifice. 12. https://cupola.gettysburg.edu/wonders_exhibit/12 This is the author's version of the work. This publication appears in Gettysburg College's institutional repository by permission of the copyright owner for personal use, not for redistribution. Cupola permanent link: https://cupola.gettysburg.edu/wonders_exhibit/12 This open access student research paper is brought to you by The uC pola: Scholarship at Gettysburg College. It has been accepted for inclusion by an authorized administrator of The uC pola. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Blue-and-White Wonder: Ming Dynasty Porcelain Plate Abstract This authentic Ming Dynasty (1368-1644) plate is a prime example of early export porcelain, a luminous substance that enthralled European collectors. The eg nerous gift of oJ yce P. Bishop in honor of her daughter, Kimberly Bishop Connors, Ming Dynasty Blue-and-White Plate is on loan from the Reeves Collection at Washington and Lee University in Lexington, Virginia. The lp ate itself is approximately 7.75 inches (20 cm) in diameter, and appears much deeper from the bottom than it does from the top. -

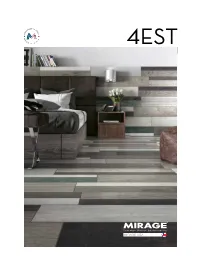

PORCELAIN TILE PORCELAIN TILE INDEX Moodboard .02 Color Palette .03 Colors & Sizes

PORCELAIN TILE PORCELAIN TILE INDEX moodboard .02 color palette .03 colors & sizes . 1 8 sizes, finishes and packaging .22 field tile application areas .23 tile performance data .23 theconcept COLLECTION With its unique style, 4est offers an original take on wood: a mix of colors and graphic patterns that move away from the traditional canons of beauty, for a modern, eye-catching mash-up. A porcelain stoneware collection with excellent technical performance, where natural and recycled wood blend together into a mood with a raw yet supremely contemporary flavor, giving rise to intense patterns and colors. 4EST collection is designed in Italy and manufactured in USA Photographed samples are intended to give an approximate idea of the product. Colors and textures shown are not binding and may vary from actual products. Samples can be ordered from Mirage U.S.A. website: www.mirageusa.net/samples inspiredMOODBOARD by paletteCOLOR Available in both warm and cold shades, is embodied by the Curry and Indigo the combination of colors with wood nuances, offering a variety of style options. 2 | | 3 curry ET01 indigo ET02 Photographed samples are intended to give an approximate idea of the product. Colors and textures shown are not binding and may vary from actual products. 4 | curry | 5 FLOOR: curry ET01 8”x40” NAT NOT RECT WALL: scraped HM20 Brick 3”x12” NAT NOT RECT 6 | | 7 curry FLOOR: curry ET01 8”x40” NAT NOT RECT WALL: scraped HM20 Brick 3”x12” NAT NOT RECT 8 | | 9 indigo FLOOR: indigo ET02 8”x40” NAT NOT RECT WALL: maioliche light taupe HM -

World Bank Document

Document of The World Bank FOR OFFICIAL USE ONLY Public Disclosure Authorized Report No: 42 124-CN PROJECT APPRAISAL DOCUMENT ON A PROPOSED LOAN Public Disclosure Authorized IN THE AMOUNT OF US$lOO MILLION TO THE PEOPLE’S REPUBLIC OF CHINA FOR A JIANGXI SHIHUTANG NAVIGATION AND HYDROPOWER COMPLEX PROJECT Public Disclosure Authorized August 14,2008 China and Mongolia Sustainable Development Unit Sustainable Development Department East Asia and Pacific Region This document has a restricted distribution and may be used by recipients only in the performance of their official duties. Its contents may not otherwise be disclosed without World Bank authorization. Public Disclosure Authorized CURRENCY EQUIVALENTS (Exchange Rate Effective January 28,2008) CurrencyUnit = RMB RMB1 = US$O.1389 US$1 = RMB7.2 FISCAL YEAR January 1 - December 31 ABBREVIATIONS AND ACRONYMS cccc China Communications Construction Company CDM Clean Development Mechanism CFU Carbon Finance Unit CGC China Guodian Corporation CPS Country Partnership Strategy CQS Selection Based on Consultants’ Qualifications DA Designated Account DP Displaced Person DSP Dam Safety Panel DWTIdwt Deadweight Tons EA Environmental Assessment EIA Environmental Impact Assessment EIRR Economic Internal Rate of Return EMP Environment Management Plan ENPV Economic Net Present Value EPP Emergency Preparedness Plan FM Financial Management FMS Financial Management Specialist FS Feasibility Study FSL Fixed Spread Loan FSR Feasibility Study Report FYP Five-Year Plan GDP Gross Domestic Product GOC Government -

Ford Ceramic Arts Columbus, Ohio

The Journal of the American Art Pottery Association, v.14, n. 2, p. 12-14, 1998. © American Art Pottery Association. http://www.aapa.info/Home/tabid/120/Default.aspx http://www.aapa.info/Journal/tabid/56/Default.aspx ISSN: 1098-8920 Ford Ceramic Arts Columbus, Ohio By James L. Murphy For about five years during the late 1930s, the combination of inventive and artistic talent pro- vided by Walter D. Ford (1906-1988) and Paul V. Bogatay (1905-1972), gave life to Ford Ceramic Arts, Inc., a small and little-known Columbus, Ohio, firm specializing in ceramic art and design. The venture, at least in the beginning, was intimately associated with Ohio State University (OSU), from which Ford graduated in 1930 with a degree in Ceramic Engineering, and where Bogatay began his tenure as an instructor of design in 1934. In fact, the first plant, begun in 1936, was actually located on the OSU campus, at 319 West Tenth Avenue, now the site of Ohio State University’s School of Nursing. There two periodic kilns produced “decorated pottery and dinnerware, molded porcelain cameos, and advertising specialties.” Ford was president and ceramic engineer; Norman M. Sullivan, secretary, treasurer, and purchasing agent; Bogatay, art director. Subsequently, the company moved to 4591 North High Street, and Ford's brother, Byron E., became vice-president. Walter, or “Flivver” Ford, as he had been known since high school, was interested primarily in the engineering aspects of the venture, and it was several of his processes for producing photographic images in relief or intaglio on ceramics that distinguished the products of the company. -

WHITE IRONSTONE NOTES VOLUME 3 No

WHITE IRONSTONE NOTES VOLUME 3 No. 2 FALL 1996 By Bev & Ernie Dieringer three sons, probably Joseph, The famous architect Mies van was the master designer of the der Rohe said, “God is in the superb body shapes that won a details.” God must have been in prize at the Crystal Palace rare form in the guise of the Exhibition in 1851. master carver who designed the Jewett said in his 1883 book handles and finials for the The Ceramic Art of Great Mayer Brothers’ Classic Gothic Britain, “Joseph died prema- registered in 1847. On page 44 turely through excessive study in Wetherbee’s collector’s guide, and application of his art. He there is an overview of the and his brothers introduced Mayer’s Gothic. However, we many improvements in the man- are going to indulge ourselves ufacture of pottery, including a and perhaps explain in words stoneware of highly vitreous and pictures, why we lovingly quality. This stoneware was collect this shape. capable of whithstanding varia- On this page, photos show tions of temperature which details of handles on the under- occurred in the brewing of tea.” trays of three T. J. & J. Mayer For this profile we couldn’t soup tureens. Top: Classic find enough of any one T. J. & J. Octagon. Middle: Mayer’s Mayer body shape, so we chose Long Octagon. Bottom: Prize a group of four shapes, includ- Bloom. ing the two beautiful octagon Elijah Mayer, patriarch of a dinner set shapes, the Classic famous family of master potters, Gothic tea and bath sets and worked in the last quarter of the Prize Bloom. -

Of the Chinese Bronze

READ ONLY/NO DOWNLOAD Ar chaeolo gy of the Archaeology of the Chinese Bronze Age is a synthesis of recent Chinese archaeological work on the second millennium BCE—the period Ch associated with China’s first dynasties and East Asia’s first “states.” With a inese focus on early China’s great metropolitan centers in the Central Plains Archaeology and their hinterlands, this work attempts to contextualize them within Br their wider zones of interaction from the Yangtze to the edge of the onze of the Chinese Bronze Age Mongolian steppe, and from the Yellow Sea to the Tibetan plateau and the Gansu corridor. Analyzing the complexity of early Chinese culture Ag From Erlitou to Anyang history, and the variety and development of its urban formations, e Roderick Campbell explores East Asia’s divergent developmental paths and re-examines its deep past to contribute to a more nuanced understanding of China’s Early Bronze Age. Campbell On the front cover: Zun in the shape of a water buffalo, Huadong Tomb 54 ( image courtesy of the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences, Institute for Archaeology). MONOGRAPH 79 COTSEN INSTITUTE OF ARCHAEOLOGY PRESS Roderick B. Campbell READ ONLY/NO DOWNLOAD Archaeology of the Chinese Bronze Age From Erlitou to Anyang Roderick B. Campbell READ ONLY/NO DOWNLOAD Cotsen Institute of Archaeology Press Monographs Contributions in Field Research and Current Issues in Archaeological Method and Theory Monograph 78 Monograph 77 Monograph 76 Visions of Tiwanaku Advances in Titicaca Basin The Dead Tell Tales Alexei Vranich and Charles Archaeology–2 María Cecilia Lozada and Stanish (eds.) Alexei Vranich and Abigail R.