1 the Willow Pattern

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Tracing the Origin of Blue and White Chinese Porcelain Ordered for the Portuguese Market During the Ming Dynasty Using INAA

Journal of Archaeological Science 40 (2013) 3046e3057 Contents lists available at SciVerse ScienceDirect Journal of Archaeological Science journal homepage: http://www.elsevier.com/locate/jas Tracing the origin of blue and white Chinese Porcelain ordered for the Portuguese market during the Ming dynasty using INAA M. Isabel Dias a,*, M. Isabel Prudêncio a, M.A. Pinto De Matos b, A. Luisa Rodrigues a a Campus Tecnológico e Nuclear/Instituto Superior Técnico, Universidade Técnica de Lisboa, EN 10 (Km 139,7), 2686-953 Sacavém, Portugal b Museu Nacional do Azulejo, Rua da Madre de Deus no 4, 1900-312 Lisboa, Portugal article info abstract Article history: The existing documentary history of Chinese porcelain ordered for the Portuguese market (mainly Ming Received 21 March 2012 dynasty.) is reasonably advanced; nevertheless detailed laboratory analyses able to reveal new aspects Received in revised form like the number and/or diversity of producing centers involved in the trade with Portugal are lacking. 26 February 2013 In this work, the chemical characterization of porcelain fragments collected during recent archaeo- Accepted 3 March 2013 logical excavations from Portugal (Lisbon and Coimbra) was done for provenance issues: identification/ differentiation of Chinese porcelain kilns used. Chemical analysis was performed by instrumental Keywords: neutron activation analysis (INAA) using the Portuguese Research Reactor. Core samples were taken from Ancient Chinese porcelain for Portuguese market the ceramic body avoiding contamination form the surface layers constituents. The results obtained so INAA far point to: (1) the existence of three main chemical-based clusters; and (2) a general attribution of the Chemical composition porcelains studied to southern China kilns; (3) a few samples are specifically attributed to Jingdezhen Ming dynasty and Zhangzhou kiln sites. -

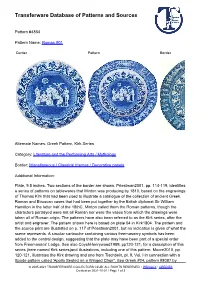

Transferware Database of Patterns and Sources

Transferware Database of Patterns and Sources Pattern #4864 Pattern Name: Roman #01 Center Pattern Border Alternate Names: Greek Pattern, Kirk Series Category: Literature and the Performing Arts / Mythology Border: Miscellaneous / Classical themes / Decorative panels Additional Information: Plate, 9.5 inches. Two sections of the border are shown. Priestman2001, pp. 114-119, identifies a series of patterns on tablewares that Minton was producing by 1810, based on the engravings of Thomas Kirk that had been used to illustrate a catalogue of the collection of ancient Greek, Roman and Etruscan vases that had been put together by the British diplomat Sir William Hamilton in the latter half of the 18thC. Minton called them the Roman patterns, though the characters portrayed were not all Roman nor were the vases from which the drawings were taken all of Roman origin. The patterns have also been referred to as the Kirk series, after the artist and engraver. The pattern shown here is based on plate 54 in Kirk1804. The pattern and the source print are illustrated on p. 117 of Priestman2001, but no indication is given of what the scene represents. A circular cartouche containing various freemasonry symbols has been added to the central design, suggesting that the plate may have been part of a special order from Freemasons' Lodge. See also CoyshHenrywood1989, pp120-121, for a description of this series (here named Kirk series)and illustrations, including one of this pattern. Moore2010, pp. 120-121, illustrates the Kirk drawing and one from Tischbein, pl. 9, Vol. I in connection with a Spode pattern called 'Apollo Seated on a Winged Chair". -

Views of a Porcelain 15

THE INFLUENCE OF GLASS TECHNOLOGY vessels nor to ceramic figurines, but to beads made in imitation of imported glass.10 The original models were ON CHINESE CERAMICS eye-beads of a style produced at numerous sites around the Mediterranean, in Central Asia and also in southern Russia, and current in the Near East since about 1500 Nigel Wood BC.11 A few polychrome glass beads found their way to Research Laboratory for Archaeology and the History of Art, University of Oxford. China in the later Bronze Age, including one example excavated from a Spring and Autumn period (770-476 BC) site in Henan province.12 This particular blue and ONE OF THE MOST IMPORTANT AND ENDURING DIFFER- white eye bead was of a style current in the eastern ences between the ceramics of China and the Near East Mediterranean in the 6th to 3rd century BC and proved lies in the role that glass has played in the establishment to have been coloured by such sophisticated, but of their respective ceramic traditions. In the ceramics of typically Near Eastern, chromophores as calcium- Mesopotamia, Persia, Egypt, and Syria glass technology antimonate-white, cobalt-blue and a copper-turquoise, proved vital for the development of glazed ceramics. while its glass was of the soda-lime type, common in 13 Figure 2. Earthenware jar with weathered glazes. Warring States Following the appearance of glazed stone-based the ancient world. period. Probably 3rd century BC (height: 9.5 cm). The British ceramics in the fourth millennium BC, the first glazes These ‘western’ beads would have been wonders in Museum. -

Asian Art at Christie's Fine Chinese Ceramics & Works Of

PRESS RELEASE | L O N D O N FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE | 24 O C T O B E R 2 0 1 8 Asian Art at Christie’s Fine Chinese Ceramics & Works of Art Including The Soame Jenyns Collection of Japanese and Chinese Art London, November 2018 London – On 6 November 2018, Christie’s Fine Chinese Ceramics & Works of Art auction will present an array of rare works of exceptional quality and with important provenance, many offered to the market for the first time in decades. The season will be highlighted by exquisite imperial ceramics, fine jade carvings, Buddhist art, huanghuali furniture, paintings from celebrated modern Chinese artists, along with works of art from a number of important collections, including The Soame Jenyns Collection of Japanese and Chinese Art. The works will be on view and open to the public from 2 to 5 November. The auction will be led by a moonflask, Bianhu, Yongzheng six-character seal mark in underglaze blue and of the period (1725-1735) (estimate on request). This magnificent flask is exceptionally large, and takes both its A Rare Large Ming-Style Blue and form and decoration from vessels made in the early 15th century. The White Moonflask, Bianhu, Yongzheng six-character seal mark Yongzheng Emperor was a keen antiquarian and a significant number of in underglaze blue and of the objects produced for his court were made in the antique style, particularly period (1725-1735) blue and white porcelain, and so their style was often adopted for imperial Estimate on request Yongzheng wares in the 18th century. -

Ming Dynasty Porcelain Plate Laura G

Wonders of Nature and Artifice Art and Art History Fall 2017 Blue-and-White Wonder: Ming Dynasty Porcelain Plate Laura G. Waters '19, Gettysburg College Follow this and additional works at: https://cupola.gettysburg.edu/wonders_exhibit Part of the Ancient, Medieval, Renaissance and Baroque Art and Architecture Commons, Fine Arts Commons, History of Science, Technology, and Medicine Commons, Industrial and Product Design Commons, and the Intellectual History Commons Share feedback about the accessibility of this item. Waters, Laura G., "Blue-and-White Wonder: Ming Dynasty Porcelain Plate" (2017). Wonders of Nature and Artifice. 12. https://cupola.gettysburg.edu/wonders_exhibit/12 This is the author's version of the work. This publication appears in Gettysburg College's institutional repository by permission of the copyright owner for personal use, not for redistribution. Cupola permanent link: https://cupola.gettysburg.edu/wonders_exhibit/12 This open access student research paper is brought to you by The uC pola: Scholarship at Gettysburg College. It has been accepted for inclusion by an authorized administrator of The uC pola. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Blue-and-White Wonder: Ming Dynasty Porcelain Plate Abstract This authentic Ming Dynasty (1368-1644) plate is a prime example of early export porcelain, a luminous substance that enthralled European collectors. The eg nerous gift of oJ yce P. Bishop in honor of her daughter, Kimberly Bishop Connors, Ming Dynasty Blue-and-White Plate is on loan from the Reeves Collection at Washington and Lee University in Lexington, Virginia. The lp ate itself is approximately 7.75 inches (20 cm) in diameter, and appears much deeper from the bottom than it does from the top. -

Chinese Ceramics in the Late Tang Dynasty

44 Chinese Ceramics in the Late Tang Dynasty Regina Krahl The first half of the Tang dynasty (618–907) was a most prosperous period for the Chinese empire. The capital Chang’an (modern Xi’an) in Shaanxi province was a magnet for international traders, who brought goods from all over Asia; the court and the country’s aristocracy were enjoying a life of luxury. The streets of Chang’an were crowded with foreigners from distant places—Central Asian, Near Eastern, and African—and with camel caravans laden with exotic produce. Courtiers played polo on thoroughbred horses, went on hunts with falconers and elegant hounds, and congregated over wine while being entertained by foreign orchestras and dancers, both male and female. Court ladies in robes of silk brocade, with jewelry and fancy shoes, spent their time playing board games on dainty tables and talking to pet parrots, their faces made up and their hair dressed into elaborate coiffures. This is the picture of Tang court life portrayed in colorful tomb pottery, created at great expense for lavish burials. By the seventh century the manufacture of sophisticated pottery replicas of men, beasts, and utensils had become a huge industry and the most important use of ceramic material in China (apart from tilework). Such earthenware pottery, relatively easy and cheap to produce since the necessary raw materials were widely available and firing temperatures relatively low (around 1,000 degrees C), was unfit for everyday use; its cold- painted pigments were unstable and its lead-bearing glazes poisonous. Yet it was perfect for creating a dazzling display at funeral ceremonies (fig. -

Phase Two Phase

Phase One 2012 2013 2014 2015 Phase Two 2016 2017 2018 2019 2020 BB B SU B BB NU BB BB Further Thoughts on Earthy Materials B MA RD Abaration Topographies of the Obsolete Receipt of Funding from Material Memory: Kunsthaus Hamburg Initial visit to Spode by KHiB staff discussion Visningsrommet USF in Bergen BB Plymouth College of Art Norwegian Artistic …When People Get to the The Post-Industrial with the British Ceramic Biennial BB End There’s Always the Brick Landscape as site for Cont(R)act earth Research Council BB Launch of website Gråsten, Denmark Creative Practice BB First Central China International BB NT topographies.khib.no Newcastle University BB Ceramics Biennale, Putting It at Stake SH BB Factory, Neil Brownsword Developing A Research Inquiry Partner Institution visits Henan Museum RIAN Design Museum, Sweden BB BB B Research Group meetings in all institutions Blås & Knåda, Stockholm into the Haptic Use of Clay as a Dancing in the Boardroom Cause and Effect Many a Slip Obsolescence and Renewal Project blog launch to map out sites for Phase Two National Centre for Craft and Design, Therapeutic Assistant Presentation of project to Museum of Contemporary Art, Marsden Woo, London NT SH m2 Gallery, London internal KHiB staff Sleaford 4th International Conference for Research BB MA NU NT RD SH Detroit Returns group in Gestalt Psychotherapy, Santiago, Chile NT SH BB MA NU NT RD SH Residency 6 NT NT SH AirSpace Gallery, Digging through Dirt: Archaeology re-turning Residency 2 Topographies of the Obsolete BB Retreat Stoke-on-Trent Topographies of the Obsolete Past, Present, Precious and Unwanted BB Participant artist reflections and discussion BB published Stoke-on-Trent BB SU B with selected artists and students. -

WHITE IRONSTONE NOTES VOLUME 3 No

WHITE IRONSTONE NOTES VOLUME 3 No. 2 FALL 1996 By Bev & Ernie Dieringer three sons, probably Joseph, The famous architect Mies van was the master designer of the der Rohe said, “God is in the superb body shapes that won a details.” God must have been in prize at the Crystal Palace rare form in the guise of the Exhibition in 1851. master carver who designed the Jewett said in his 1883 book handles and finials for the The Ceramic Art of Great Mayer Brothers’ Classic Gothic Britain, “Joseph died prema- registered in 1847. On page 44 turely through excessive study in Wetherbee’s collector’s guide, and application of his art. He there is an overview of the and his brothers introduced Mayer’s Gothic. However, we many improvements in the man- are going to indulge ourselves ufacture of pottery, including a and perhaps explain in words stoneware of highly vitreous and pictures, why we lovingly quality. This stoneware was collect this shape. capable of whithstanding varia- On this page, photos show tions of temperature which details of handles on the under- occurred in the brewing of tea.” trays of three T. J. & J. Mayer For this profile we couldn’t soup tureens. Top: Classic find enough of any one T. J. & J. Octagon. Middle: Mayer’s Mayer body shape, so we chose Long Octagon. Bottom: Prize a group of four shapes, includ- Bloom. ing the two beautiful octagon Elijah Mayer, patriarch of a dinner set shapes, the Classic famous family of master potters, Gothic tea and bath sets and worked in the last quarter of the Prize Bloom. -

N C C Newc Coun Counc Jo Castle Ncil a Cil St Oint C E-Und Nd S Tatem

Newcastle-under-Lyme Borough Council and Stoke-on-Trent City Council Statement of Community Involvement Joint Consultation Report July 2015 Table of Contents Introduction Page 3 Regulations Page 3 Consultation Page 3 How was the consultation on Page 3 the Draft Joint SCI undertaken and who was consulted Main issues raised in Page 7 consultation responses on Draft Joint SCI Main changes made to the Page 8 Draft Joint SCI Appendices Page 12 Appendix 1 Copy of Joint Page 12 Press Release Appendix 2 Summary list of Page 14 who was consulted on the Draft SCI Appendix 3 Draft SCI Page 31 Consultation Response Form Appendix 4 Table of Page 36 Representations, officer response and proposed changes 2 Introduction This Joint Consultation Report sets out how the consultation on the Draft Newcastle-under- Lyme Borough Council and Stoke-on-Trent City Council Statement of Community Involvement (SCI) was undertaken, who was consulted, a summary of main issues raised in the consultation responses and a summary of how these issues have been considered. The SCI was adopted by Newcastle-under-Lyme Borough Council on the 15th July 2015 and by Stoke-on-Trent City Council on the 9th July 2015. Prior to adoption, Newcastle-under-Lyme Borough Council and Stoke-on-Trent City Council respective committees and Cabinets have considered the documents. Newcastle-under- Lyme Borough Council’s Planning Committee considered a report on the consultation responses and suggested changes to the SCI on the 3RD June 2015 and recommended a grammatical change at paragraph 2.9 (replacing the word which with who) and this was reported to DMPG on the 9th June 2015. -

China: Qing Dynasty Porcelain and Global Exchange Pre-Visit

China: Qing Dynasty Porcelain and Global Exchange Pre-Visit Share this background information with students before your Distance Learning session. Grade Level: Grades 9-12 Collection: East Asian Art Culture/Region: China, East Asia Subject Area: History and Social Science Activity Type: Distance Learning WHY LOOK AT PLATES AND VASES? When visiting a relative or a fancy restaurant, perhaps you have dined on “fine china.” While today we appreciate porcelain dinnerware for the refinement it can add to an occasion, this conception is founded on centuries of exchange between Asian and Western markets. Chinese porcelain production has a long history of experimentation, innovation, and inspiration resulting in remarkably beautiful examples of form and imagery. At the VMFA, you will examine objects from a small portion of this history — the 18th century during the Qing Dynasty — to expand your understanding of global exchange in this era. Because they were made for trade outside of China, these objects are categorized as export porcelain by collectors and art historians. Review the background information below, and think of a few answers you want to look for when you visit VMFA. QING DYNASTY Emperors, Arts, and Trade Around the end of the 16th century, a Jurchin leader named Nurhaci (1559–1626) brought together various nomadic groups who became known as the Manchus. His forces quickly conquered the area of present-day Manchuria, and his heirs set their sights on China. In 1636 the Manchus chose the new name of Qing, meaning “pure,” to emphasize their intention to purify China by seizing power from the Ming dynasty. -

Stoke-On-Trent (Uk) Policy Brief #4 • Liveability

STOKE-ON-TRENT (UK) POLICY BRIEF #4 • LIVEABILITY EXECUTIVE SUMMARY This policy brief showcases a successful initiative to improve urban liveability in a shrinking city through repurposing its historical heritage. It shows how old industrial buildings could be used to accommodate new creative arts entrepreneurs and host high profile cultural events. The brief focusses on Spode Works, a 10-acre bone china pottery and homewares production site located in Stoke-on-Trent – a medium-size polycentric industrial city in central England1, coping with population loss. Building on local knowledge and stakeholders’ experiences of using the Spode site after the factory’s closure in 2009, this brief demonstrates how a shrinking city can challenge a negative stereotype, raise its profile, and improve attractiveness by generating new creative arts and culture dynamics from within the effectively repurposed old industrial assets. The key lesson learnt is that to enhance liveability one should not drive it down to specific concerns like housing, jobs, or leisure. Urban liveability is about the dynamism and wider significance of a place. These qualities can be improved by a visionary local authority, enthusiastic civil society, and risk-taking private sector partners, all committed to urban regeneration and raising the city profile through the development of local creative capacity for impactful events and knowledge exchange. INTRODUCTION Over the last two decades, Stoke-on-Trent actors have undertaken a series of initiatives aimed at making the city more attractive and liveable, including improvements in the social and private sector housing provision, tourist infrastructure developments, and civic-led creative arts projects. The local art and culture community and other stakeholders have acknowledged the city’s untapped potential for creativity and innovation. -

Page 1 578 a Japanese Porcelain Polychrome Kendi, Kutani, 17Th C

Ordre Designation Estimation Estimation basse haute 551 A Chinese mythological bronze group, 19/20th C. H: 28 cm 250 350 552 A Chinese bronze elongated bottle-shaped vase, Ming Dynasty H.: 31 600 1200 cm 553 A partial gilt seated bronze buddha, Yongzheng mark, 19th C. or earlier 800 1200 H: 39 cm L: 40 cm Condition: good. The gold paint somewhat worn. 554 A Chinese bronze jardiniere on wooden stand, 19/20th C. H.: 32 cm 300 600 555 A Chinese figural bronze incense burner, 17/18th C. H.: 29 cm 1000 1500 556 A Chinese bronze and cloisonne figure of an immortal, 18/19th C. H.: 31 300 600 cm 557 A Chinese bronze figure of an emperor on a throne, 18/19th C. H.: 30 cm 800 1200 Condition: missing a foot on the right bottom side. 558 A bronze figure of Samanthabadra, inlaid with semi-precious stones, 4000 8000 Ming Dynasty H: 28 cm 559 A Chinese gilt bronze seated buddha and a bronze Tara, 18/19th C. H.: 600 1200 14 cm (the tallest) 560 A Chinese bronze tripod incense burner with trigrams, 18/19th C. H.: 350 700 22,3 cm 561 A tall pair of Chinese bronze “Luduan� figures, 18/19th C. H.: 29 1200 1800 cm 562 A tall gilt bronze head of a Boddhisatva with semi-precious stones, Tibet, 1000 1500 17/18th C. H.: 33 cm 563 A dark bronze animal subject group, China, Ming Dynasty, 15-16th C. H.: 1500 2500 25,5 cm 564 A Chinese dragon censer in champlevé enameled bronze, 18/19th C.