From the Zhou to Qing Dynasties)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Eastern Zhou Dynasty \(770 – 221BC\)

Eastern Zhou Dynasty (770 – 221BC) The long period during which the Zhou nominally ruled China is divided into two parts: the Western Zhou, covering the years from the conquest in c. 1050BC to the move of the capital from Xi’an to Luoyang in 771BC, and the Eastern Zhou, during which China was subdivided into many small states fro 770BC to the ascendancy of the Qin kingdom in 221BC. The Eastern Zhou period is traditionally divided into two: the Spring and Autumn period (770 – 475BC) and the period of the Warring States (475 – 221BC). These names are taken from contemporary historical documents which describe the periods in question. After the conquest of Xi’an by the Quanrong, the Zhou established their capital at Luoyang. No longer did they control their territory as undisputed kings, but now ruled alongside a number of other equally or more powerful rulers. In the centre and the north, the state of Jin was dominant, while the states of Yan and Qi occupied the present-day provinces of Hebei and Shandong repectively. Jin disintegrated in the fifth century BC, and three states, Han, Wei and Zhao, assumed its territory. In the west the Qin succeeded to the mantle of the Zhou, and in the south the state of Chu dominated the Yanzi basin. During the sixth and fifth centuries BC, Chu threatened and then swallowed up the small eastern states of Wu and Yue, as well as states such as Zeng on its northern boundary. Although for much of the period Chu was a successful and dominant power, in due course it fell in 223BC before the might of Qin, its rulers fleeing eastwards to Anhui province. -

Kūnqǔ in Practice: a Case Study

KŪNQǓ IN PRACTICE: A CASE STUDY A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE DIVISION OF THE UNIVERSITY OF HAWAI‘I AT MĀNOA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY IN THEATRE OCTOBER 2019 By Ju-Hua Wei Dissertation Committee: Elizabeth A. Wichmann-Walczak, Chairperson Lurana Donnels O’Malley Kirstin A. Pauka Cathryn H. Clayton Shana J. Brown Keywords: kunqu, kunju, opera, performance, text, music, creation, practice, Wei Liangfu © 2019, Ju-Hua Wei ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I wish to express my gratitude to the individuals who helped me in completion of my dissertation and on my journey of exploring the world of theatre and music: Shén Fúqìng 沈福庆 (1933-2013), for being a thoughtful teacher and a father figure. He taught me the spirit of jīngjù and demonstrated the ultimate fine art of jīngjù music and singing. He was an inspiration to all of us who learned from him. And to his spouse, Zhāng Qìnglán 张庆兰, for her motherly love during my jīngjù research in Nánjīng 南京. Sūn Jiàn’ān 孙建安, for being a great mentor to me, bringing me along on all occasions, introducing me to the production team which initiated the project for my dissertation, attending the kūnqǔ performances in which he was involved, meeting his kūnqǔ expert friends, listening to his music lessons, and more; anything which he thought might benefit my understanding of all aspects of kūnqǔ. I am grateful for all his support and his profound knowledge of kūnqǔ music composition. Wichmann-Walczak, Elizabeth, for her years of endeavor producing jīngjù productions in the US. -

Archaeological Observation on the Exploration of Chu Capitals

Archaeological Observation on the Exploration of Chu Capitals Wang Hongxing Key words: Chu Capitals Danyang Ying Chenying Shouying According to accurate historical documents, the capi- In view of the recent research on the civilization pro- tals of Chu State include Danyang 丹阳 of the early stage, cess of the middle reach of Yangtze River, we may infer Ying 郢 of the middle stage and Chenying 陈郢 and that Danyang ought to be a central settlement among a Shouying 寿郢 of the late stage. Archaeologically group of settlements not far away from Jingshan 荆山 speaking, Chenying and Shouying are traceable while with rice as the main crop. No matter whether there are the locations of Danyang and Yingdu 郢都 are still any remains of fosses around the central settlement, its oblivious and scholars differ on this issue. Since Chu area must be larger than ordinary sites and be of higher capitals are the political, economical and cultural cen- scale and have public amenities such as large buildings ters of Chu State, the research on Chu capitals directly or altars. The site ought to have definite functional sec- affects further study of Chu culture. tions and the cemetery ought to be divided into that of Based on previous research, I intend to summarize the aristocracy and the plebeians. The relevant docu- the exploration of Danyang, Yingdu and Shouying in ments and the unearthed inscriptions on tortoise shells recent years, review the insufficiency of the former re- from Zhouyuan 周原 saying “the viscount of Chu search and current methods and advance some personal (actually the ruler of Chu) came to inform” indicate that opinion on the locations of Chu capitals and later explo- Zhou had frequent contact and exchange with Chu. -

The Web That Has No Weaver

THE WEB THAT HAS NO WEAVER Understanding Chinese Medicine “The Web That Has No Weaver opens the great door of understanding to the profoundness of Chinese medicine.” —People’s Daily, Beijing, China “The Web That Has No Weaver with its manifold merits … is a successful introduction to Chinese medicine. We recommend it to our colleagues in China.” —Chinese Journal of Integrated Traditional and Chinese Medicine, Beijing, China “Ted Kaptchuk’s book [has] something for practically everyone . Kaptchuk, himself an extraordinary combination of elements, is a thinker whose writing is more accessible than that of Joseph Needham or Manfred Porkert with no less scholarship. There is more here to think about, chew over, ponder or reflect upon than you are liable to find elsewhere. This may sound like a rave review: it is.” —Journal of Traditional Acupuncture “The Web That Has No Weaver is an encyclopedia of how to tell from the Eastern perspective ‘what is wrong.’” —Larry Dossey, author of Space, Time, and Medicine “Valuable as a compendium of traditional Chinese medical doctrine.” —Joseph Needham, author of Science and Civilization in China “The only approximation for authenticity is The Barefoot Doctor’s Manual, and this will take readers much further.” —The Kirkus Reviews “Kaptchuk has become a lyricist for the art of healing. And the more he tells us about traditional Chinese medicine, the more clearly we see the link between philosophy, art, and the physician’s craft.” —Houston Chronicle “Ted Kaptchuk’s book was inspirational in the development of my acupuncture practice and gave me a deep understanding of traditional Chinese medicine. -

Local Authority in the Han Dynasty: Focus on the Sanlao

Local Authority in the Han Dynasty: Focus on the Sanlao Jiandong CHEN 㱩ڎ暒 School of International Studies Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences University of Technology Sydney Australia A thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Technology Sydney Sydney, Australia 2018 Certificate of Original Authorship I certify that the work in this thesis has not previously been submitted for a degree nor has it been submitted as part of requirements for a degree except as fully acknowledged within the text. I also certify that the thesis has been written by me. Any help that I have received in my research work and the preparation of the thesis itself has been acknowledged. In addition, I certify that all information sources and literature used are indicated in the thesis. This thesis is the result of a research candidature conducted with another University as part of a collaborative Doctoral degree. Production Note: Signature of Student: Signature removed prior to publication. Date: 30/10/2018 ii Acknowledgements The completion of the thesis would not have been possible without the help and support of many people. Firstly, I would like to express my sincere gratitude to my supervisor, Associate Professor Jingqing Yang for his continuous support during my PhD study. Many thanks for providing me with the opportunity to study at the University of Technology Sydney. His patience, motivation and immense knowledge guided me throughout the time of my research. I cannot imagine having a better supervisor and mentor for my PhD study. Besides my supervisor, I would like to thank the rest of my thesis committee: Associate Professor Chongyi Feng and Associate Professor Shirley Chan, for their insightful comments and encouragement; and also for their challenging questions which incited me to widen my research and view things from various perspectives. -

Transmission of Han Pictorial Motifs Into the Western Periphery: Fuxi and Nüwa in the Wei-Jin Mural Tombs in the Hexi Corridor*8

DOI: 10.4312/as.2019.7.2.47-86 47 Transmission of Han Pictorial Motifs into the Western Periphery: Fuxi and Nüwa in the Wei-Jin Mural Tombs in the Hexi Corridor*8 ∗∗ Nataša VAMPELJ SUHADOLNIK 9 Abstract This paper examines the ways in which Fuxi and Nüwa were depicted inside the mu- ral tombs of the Wei-Jin dynasties along the Hexi Corridor as compared to their Han counterparts from the Central Plains. Pursuing typological, stylistic, and iconographic approaches, it investigates how the western periphery inherited the knowledge of the divine pair and further discusses the transition of the iconographic and stylistic design of both deities from the Han (206 BCE–220 CE) to the Wei and Western Jin dynasties (220–316). Furthermore, examining the origins of the migrants on the basis of historical records, it also attempts to discuss the possible regional connections and migration from different parts of the Chinese central territory to the western periphery. On the basis of these approaches, it reveals that the depiction of Fuxi and Nüwa in Gansu area was modelled on the Shandong regional pattern and further evolved into a unique pattern formed by an iconographic conglomeration of all attributes and other physical characteristics. Accordingly, the Shandong region style not only spread to surrounding areas in the central Chinese territory but even to the more remote border regions, where it became the model for funerary art motifs. Key Words: Fuxi, Nüwa, the sun, the moon, a try square, a pair of compasses, Han Dynasty, Wei-Jin period, Shandong, migration Prenos slikovnih motivov na zahodno periferijo: Fuxi in Nüwa v grobnicah s poslikavo iz obdobja Wei Jin na območju prehoda Hexi Izvleček Pričujoči prispevek v primerjalni perspektivi obravnava upodobitev Fuxija in Nüwe v grobnicah s poslikavo iz časa dinastij Wei in Zahodni Jin (220–316) iz province Gansu * The author acknowledges the financial support of the Slovenian Research Agency (ARRS) in the framework of the research core funding Asian languages and Cultures (P6-0243). -

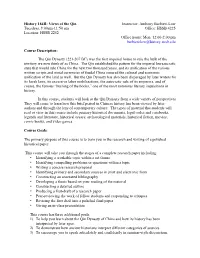

Views of the Qin Instructor: Anthony Barbieri-Low Tuesdays, 9:00Am-11:50 Am Office: HSSB 4225 Location: HSSB 2252 Office Hours: Mon

History 184R: Views of the Qin Instructor: Anthony Barbieri-Low Tuesdays, 9:00am-11:50 am Office: HSSB 4225 Location: HSSB 2252 Office hours: Mon. 12:00-2:00 pm [email protected] Course Description: The Qin Dynasty (221-207 BC) was the first imperial house to rule the bulk of the territory we now think of as China. The Qin established the pattern for the imperial bureaucratic state that would rule China for the next two thousand years, and its unification of the various written scripts and metal currencies of feudal China ensured the cultural and economic unification of the land as well. But the Qin Dynasty has also been disparaged by later writers for its harsh laws, its excessive labor mobilizations, the autocratic rule of its emperors, and of course, the famous “burning of the books,” one of the most notorious literary inquisitions in history. In this course, students will look at the Qin Dynasty from a wide variety of perspectives. They will come to learn how this brief period in Chinese history has been viewed by later authors and through the lens of contemporary culture. The types of material that students will read or view in this course include primary historical documents, legal codes and casebooks, legends and literature, historical essays, archaeological materials, historical fiction, movies, comic books, and video games. Course Goals: The primary purpose of this course is to train you in the research and writing of a polished historical paper. This course will take you through the stages of a complete research paper -

The Role of Experts and Scholars in Community Conflict Resolution: A

Negotiation and Conflict Management Research The Role of Experts and Scholars in Community Conflict Resolution: A Comparative Analysis of Two Cases in China Lihua Yang School of Government, Peking University, Beijing, China Keywords Abstract case study, cross-culture, community conflict resolution, In this article, I draw from two case studies to explore the role of experts experts, scholars, trust chain. and scholars (ES), as a special third party, in community conflict resolu- tion in contemporary China. Findings include that local ES are more Correspondence likely to play the roles as leaders, organizers of farmers, and as agents of Lihua Yang, School of government. Nonlocal ES are more likely to play the roles as information Government, The Leo KoGuan providers and as pure self-interest pursuers. This study also reveals that, Building, Peking University, No. 5 Yiheyuan Road, Beijing although their knowledge and information are important, knowledge and 100871, China; e-mails: information are only preconditions for ES’s participation. Their social [email protected]; capital–rather than the knowledge and information they possess–differen- [email protected]. tiates the effectiveness of their participation in governance and the facili- tation of community conflict resolution. Local ES with high social capital doi: 10.1111/ncmr.12134 are more effective in governance and facilitating community conflict res- olution than nonlocal ES without high social capital. Introduction Conflicts are one of the key issues challenging social governance. Among the studies on conflict, the research on community conflict resolution in social governance is definitely an important subject (e.g., Amy, 1987; Avruch, Black, & Scimecca, 1991; Cairns, 1992; Dukes, 2004; Emerson, Orr, Keyes, & McKinght, 2009; Jeong, 2008; Kriesberg, 1998; Magid, 1967; Pruitt & Kim, 2004; Rabbie, 1994; Stephen- son & Pops, 1989; Zubek, Pruitt, McGillicuddy, Peirce, & Syna, 1992). -

Chapter Three – the Zhou Dynasty and the Warring States

CHAPTER THREE – THE ZHOU DYNASTY AND THE WARRING STATES THE OVERTHROW OF THE SHANG As our archaeological record has proven, outside of Shang territory there existed a myriad of other kingdoms and peoples – some were allied to the Shang, others were hostile. Between the Shang capital at Anyang and the territory of the Qiang peoples, was a kingdom named Zhou. A nomadic peoples who spoke an early form of the Tibetan language, the Qiang tribes were often at war with the Shang kingdom. Serving as a buffer zone against the Qiang, this frontier kingdom of Zhou shared much of the Shang’s material culture, such as its bronze work. In 1045 BCE, however, the Zhou noble family of Ji rebelled against and overthrew the Shang rulers at Anyang. In doing so, they laid the foundations for the Zhou dynasty, China’s third. In classical Chinese history, three key figures are involved in the overthrow of the Shang. They are King Wen, who originally expanded the Zhou realm, his son King Wu, who conquered the Shang, and King Wu’s brother, known as the duke of Zhou, who secured Zhou authority while serving as regent for King Wu’s heir. The deeds of these three men are recorded in China’s earliest transmitted text, The Book of Documents.The text portrays the Shang kings as corrupt and decadent, with the Zhou victory recorded as a result of their justice and virtue. The Zhou kings shifted the Shang system of religious worship away from Di, who was a personified supreme first ancestor figure and towards Tian, which was Heaven itself. -

The Later Han Empire (25-220CE) & Its Northwestern Frontier

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations 2012 Dynamics of Disintegration: The Later Han Empire (25-220CE) & Its Northwestern Frontier Wai Kit Wicky Tse University of Pennsylvania, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations Part of the Asian History Commons, Asian Studies Commons, and the Military History Commons Recommended Citation Tse, Wai Kit Wicky, "Dynamics of Disintegration: The Later Han Empire (25-220CE) & Its Northwestern Frontier" (2012). Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations. 589. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/589 This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/589 For more information, please contact [email protected]. Dynamics of Disintegration: The Later Han Empire (25-220CE) & Its Northwestern Frontier Abstract As a frontier region of the Qin-Han (221BCE-220CE) empire, the northwest was a new territory to the Chinese realm. Until the Later Han (25-220CE) times, some portions of the northwestern region had only been part of imperial soil for one hundred years. Its coalescence into the Chinese empire was a product of long-term expansion and conquest, which arguably defined the egionr 's military nature. Furthermore, in the harsh natural environment of the region, only tough people could survive, and unsurprisingly, the region fostered vigorous warriors. Mixed culture and multi-ethnicity featured prominently in this highly militarized frontier society, which contrasted sharply with the imperial center that promoted unified cultural values and stood in the way of a greater degree of transregional integration. As this project shows, it was the northwesterners who went through a process of political peripheralization during the Later Han times played a harbinger role of the disintegration of the empire and eventually led to the breakdown of the early imperial system in Chinese history. -

Do Not Kill the Goose That Lays Golden Eggs: the Reasons of the Deficiencies in China’S Intellectual Property Rights Protection

DO NOT KILL THE GOOSE THAT LAYS GOLDEN EGGS: THE REASONS OF THE DEFICIENCIES IN CHINA’S INTELLECTUAL PROPERTY RIGHTS PROTECTION XIUYI ZHENG MPhil University of York Law March 2015 Abstract China’s intellectual property protection, which has been considered weak and discussed for decades, is playing an increasingly significant role in global trading. In the past decades, China has made great strikes in its intellectual property rights (IPR) protection, while its performance is still not satisfactory, especially in the eyes of developed countries. Before taking any further coercive strategies, both developed countries and China should look into the reasons of the deficiencies in China’s IPR protection so that measures could be taken more efficiently. This thesis will focus on the detailed history of the development of China’s IPR protection with a historical method, thus justifying the theory that late start and slow development are the main two reasons of the deficiencies in China’s IPR system. The concept of IPR did not exist in China until the end of 19th century due to the influence of Confucianism. The weak awareness of IPR lasted till now. From the day that western forces brought the idea of IPR into China to the establishment of a genuine protection system, China experienced a violent social turbulence with many changes in regimes and guiding ideologies. Meanwhile, Chinese government was continuously in the dilemma: whether they should pursuit a better IPR protection system or learn advanced knowledge and technologies from developed countries. All these factors slowed down the development of IPR in China. -

The Birth of Chinese Feminism Columbia & Ko, Eds

& liu e-yin zHen (1886–1920?) was a theo- ko Hrist who figured centrally in the birth , karl of Chinese feminism. Unlike her contem- , poraries, she was concerned less with China’s eds fate as a nation and more with the relation- . , ship among patriarchy, imperialism, capi- talism, and gender subjugation as global historical problems. This volume, the first translation and study of He-Yin’s work in English, critically reconstructs early twenti- eth-century Chinese feminist thought in a transnational context by juxtaposing He-Yin The Bir Zhen’s writing against works by two better- known male interlocutors of her time. The editors begin with a detailed analysis of He-Yin Zhen’s life and thought. They then present annotated translations of six of her major essays, as well as two foundational “The Birth of Chinese Feminism not only sheds light T on the unique vision of a remarkable turn-of- tracts by her male contemporaries, Jin h of Chinese the century radical thinker but also, in so Tianhe (1874–1947) and Liang Qichao doing, provides a fresh lens through which to (1873–1929), to which He-Yin’s work examine one of the most fascinating and com- responds and with which it engages. Jin, a poet and educator, and Liang, a philosopher e plex junctures in modern Chinese history.” Theory in Transnational ssential Texts Amy— Dooling, author of Women’s Literary and journalist, understood feminism as a Feminism in Twentieth-Century China paternalistic cause that liberals like them- selves should defend. He-Yin presents an “This magnificent volume opens up a past and alternative conception that draws upon anar- conjures a future.