Proquest Dissertations

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Post-Soviet Political Party Development in Russia: Obstacles to Democratic Consolidation

POST-SOVIET POLITICAL PARTY DEVELOPMENT IN RUSSIA: OBSTACLES TO DEMOCRATIC CONSOLIDATION Evguenia Lenkevitch Bachelor of Arts (Honours), SFU 2005 THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS In the Department of Political Science O Evguenia Lenkevitch 2007 SIMON FRASER UNIVERSITY 2007 All rights reserved. This work may not be reproduced in whole or in part, by photocopy or other means, without permission of the author. APPROVAL Name: Evguenia Lenkevitch Degree: Master of Arts, Department of Political Science Title of Thesis: Post-Soviet Political Party Development in Russia: Obstacles to Democratic Consolidation Examining Committee: Chair: Dr. Lynda Erickson, Professor Department of Political Science Dr. Lenard Cohen, Professor Senior Supervisor Department of Political Science Dr. Alexander Moens, Professor Supervisor Department of Political Science Dr. llya Vinkovetsky, Assistant Professor External Examiner Department of History Date DefendedlApproved: August loth,2007 The author, whose copyright is declared on the title page of this work, has granted to Simon Fraser University the right to lend this thesis, project or extended essay to users of the Simon Fraser University Library, and to make partial or single copies only for such users or in response to a request from the library of any other university, or other educational institution, on its own behalf or for one of its users. The author has further granted permission to Simon Fraser University to keep or make a digital copy for use in its circulating collection (currently available to the public at the 'Institutional Repository" link of the SFU Library website <www.lib.sfu.ca> at: <http://ir.lib.sfu.ca/handle/1892/112>) and, without changing the content, to translate the thesis/project or extended essays, if technically possible, to any medium or format for the purpose of preservation of the digital work. -

Network Map of Knowledge And

Humphry Davy George Grosz Patrick Galvin August Wilhelm von Hofmann Mervyn Gotsman Peter Blake Willa Cather Norman Vincent Peale Hans Holbein the Elder David Bomberg Hans Lewy Mark Ryden Juan Gris Ian Stevenson Charles Coleman (English painter) Mauritz de Haas David Drake Donald E. Westlake John Morton Blum Yehuda Amichai Stephen Smale Bernd and Hilla Becher Vitsentzos Kornaros Maxfield Parrish L. Sprague de Camp Derek Jarman Baron Carl von Rokitansky John LaFarge Richard Francis Burton Jamie Hewlett George Sterling Sergei Winogradsky Federico Halbherr Jean-Léon Gérôme William M. Bass Roy Lichtenstein Jacob Isaakszoon van Ruisdael Tony Cliff Julia Margaret Cameron Arnold Sommerfeld Adrian Willaert Olga Arsenievna Oleinik LeMoine Fitzgerald Christian Krohg Wilfred Thesiger Jean-Joseph Benjamin-Constant Eva Hesse `Abd Allah ibn `Abbas Him Mark Lai Clark Ashton Smith Clint Eastwood Therkel Mathiassen Bettie Page Frank DuMond Peter Whittle Salvador Espriu Gaetano Fichera William Cubley Jean Tinguely Amado Nervo Sarat Chandra Chattopadhyay Ferdinand Hodler Françoise Sagan Dave Meltzer Anton Julius Carlson Bela Cikoš Sesija John Cleese Kan Nyunt Charlotte Lamb Benjamin Silliman Howard Hendricks Jim Russell (cartoonist) Kate Chopin Gary Becker Harvey Kurtzman Michel Tapié John C. Maxwell Stan Pitt Henry Lawson Gustave Boulanger Wayne Shorter Irshad Kamil Joseph Greenberg Dungeons & Dragons Serbian epic poetry Adrian Ludwig Richter Eliseu Visconti Albert Maignan Syed Nazeer Husain Hakushu Kitahara Lim Cheng Hoe David Brin Bernard Ogilvie Dodge Star Wars Karel Capek Hudson River School Alfred Hitchcock Vladimir Colin Robert Kroetsch Shah Abdul Latif Bhittai Stephen Sondheim Robert Ludlum Frank Frazetta Walter Tevis Sax Rohmer Rafael Sabatini Ralph Nader Manon Gropius Aristide Maillol Ed Roth Jonathan Dordick Abdur Razzaq (Professor) John W. -

A Precarious Peace 1 Michael Mcfaul Domestic Politics in the Making of Russian Foreign Policy

A Precarious Peace 1 Michael McFaul Domestic Politics in the Making of Russian Foreign Policy I Throughout the his- tory of the modem world, domestic regime change-be it democratization, automatization, decolonization, decommunization, federal dissolution, coups, or revolutions-has often triggered international conflict and war. When a regime changes, decaying institutions from the ancien regime compete with new rules of the game to shape political competition in ambiguous ways. This uncertain context provides opportunities for political actors, both new and old, to pursue new strategies for achieving their objectives, including belligerent policies against both domestic and international foes. In desperation, losers from regime change may resort to violence to maintain their former privileges. Such internal conflicts become international wars when these interest groups who benefited from the old order call upon their allies to intervene on their behalf or strike out against their enemies as a means to shore up their domestic legitimacy. In the name of democracy, independence, the revolution, or the nation, the beneficiaries of regime change also can resort to violence against both domestic and international opponents to secure their new gains. The protracted regime transformation under way in Russia seems like a probable precipitant of international conflict. Over the last decade, old political institutions have collapsed while new democratic institutions have yet to be consolidated. Concurrently, political figures, organizations, and interest groups that benefited from the old Soviet order have incurred heavy losses in the new Russian polity. The new, ambiguous institutional context also has allowed militant, imperialist political entrepreneurs to assume salient roles in Russian politics. -

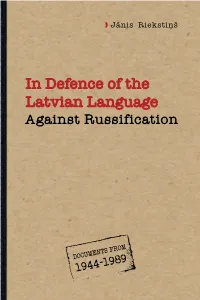

In Defence of the Latvian Language Against Russification. Documents from 1944-1989

the Jānis Riekstiņš of Language Defence In Latvian Against Russification Jānis Riekstiņš In Defence of the Latvian Language Against Russification Jānis Riekstiņš In Defence of the Latvian Language Against Russification The Latvian Language Agency Jānis Riekstiņš In Defence of the Latvian Language Against Russification Riga Latviešu valodas aģentūra / The Latvian Language Agency 2012 UDK 811.174’ 272(474.3)(093) De 167 Jānis Riekstiņš In Defence of the Latvian Language Against Russification 1944–1989 Documents In Defence of the Latvian Language Against Russification. 1944–1989. Documents. Compiled and translated from the Russian by J. Riekstiņš. Introduction by Prof. Uldis Ozoliņš, foreword by J. Riekstiņš. Managing editor D. Liepa. Riga: LVA, 2012. 160 pages. Managing editor Dr. Dite Liepa Literary editor P. Cedriņš Reviewer Dr. Dzintra Hirša Documents utilized are from the Latvian State Archive collection of LCP CC records (PA-101. fonds), LCP Central Control and Auditing Committee (PA-2160), the LSSR Council of Ministers (270. fonds), LSSR Supreme Council (290. fonds), the Riga City Executive Committee (1400. fonds), as well as documents from collections of other institutions, that verify the Soviet policies in Latvian SSR. Many of these documents are published for the first time. Cover design and layout: Vanda Voiciša © LVA, 2012 © Jānis Riekstiņš, compiler, translator from the Russian language, foreword author © Uldis Ozoliņš, foreword author © Vanda Voiciša, “Idea lex”, cover design and layout ISBN 978-9984-815-77-0 Table of Contents Introduction: the struggle for the status of the Latvian language during the Soviet occupation 1944 to 1989 ............ 6 Foreword by J. Riekstiņš ........................................18 Section 1 Decisions and materials on the acquisition of the Latvian language .........................21 Section 2 Decisions on learning Russian. -

Reform and Human Rights the Gorbachev Record

100TH-CONGRESS HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES [ 1023 REFORM AND HUMAN RIGHTS THE GORBACHEV RECORD REPORT SUBMITTED TO THE CONGRESS OF THE UNITED STATES BY THE COMMISSION ON SECURITY AND COOPERATION IN EUROPE MAY 1988 Printed for the use of the Commission on Security and Cooperation in Europe U.S. GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE WASHINGTON: 1988 84-979 = For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, Congressional Sales Office U.S. Government Printing Office, Washington, DC 20402 COMMISSION ON SECURITY AND COOPERATION IN EUROPE STENY H. HOYER, Maryland, Chairman DENNIS DeCONCINI, Arizona, Cochairman DANTE B. FASCELL, Florida FRANK LAUTENBERG, New Jersey EDWARD J. MARKEY, Massachusetts TIMOTHY WIRTH, Colorado BILL RICHARDSON, New Mexico WYCHE FOWLER, Georgia EDWARD FEIGHAN, Ohio HARRY REED, Nevada DON RITTER, Pennslyvania ALFONSE M. D'AMATO, New York CHRISTOPHER H. SMITH, New Jersey JOHN HEINZ, Pennsylvania JACK F. KEMP, New York JAMES McCLURE, Idaho JOHN EDWARD PORTER, Illinois MALCOLM WALLOP, Wyoming EXECUTIvR BRANCH HON. RICHARD SCHIFIER, Department of State Vacancy, Department of Defense Vacancy, Department of Commerce Samuel G. Wise, Staff Director Mary Sue Hafner, Deputy Staff Director and General Counsel Jane S. Fisher, Senior Staff Consultant Michael Amitay, Staff Assistant Catherine Cosman, Staff Assistant Orest Deychakiwsky, Staff Assistant Josh Dorosin, Staff Assistant John Finerty, Staff Assistant Robert Hand, Staff Assistant Gina M. Harner, Administrative Assistant Judy Ingram, Staff Assistant Jesse L. Jacobs, Staff Assistant Judi Kerns, Ofrice Manager Ronald McNamara, Staff Assistant Michael Ochs, Staff Assistant Spencer Oliver, Consultant Erika B. Schlager, Staff Assistant Thomas Warner, Pinting Clerk (11) CONTENTS Page Summary Letter of Transmittal .................... V........................................V Reform and Human Rights: The Gorbachev Record ................................................ -

A Survey of Groups, Individuals, Strategies and Prospects the Russia Studies Centre at the Henry Jackson Society

The Russian Opposition: A Survey of Groups, Individuals, Strategies and Prospects The Russia Studies Centre at the Henry Jackson Society By Julia Pettengill Foreword by Chris Bryant MP 1 First published in 2012 by The Henry Jackson Society The Henry Jackson Society 8th Floor – Parker Tower, 43-49 Parker Street, London, WC2B 5PS Tel: 020 7340 4520 www.henryjacksonsociety.org © The Henry Jackson Society, 2012 All rights reserved The views expressed in this publication are those of the author and are not necessarily indicative of those of The Henry Jackson Society or its directors Designed by Genium, www.geniumcreative.com ISBN 978-1-909035-01-0 2 About The Henry Jackson Society The Henry Jackson Society: A cross-partisan, British think-tank. Our founders and supporters are united by a common interest in fostering a strong British, European and American commitment towards freedom, liberty, constitutional democracy, human rights, governmental and institutional reform and a robust foreign, security and defence policy and transatlantic alliance. The Henry Jackson Society is a company limited by guarantee registered in England and Wales under company number 07465741 and a charity registered in England and Wales under registered charity number 1140489. For more information about Henry Jackson Society activities, our research programme and public events please see www.henryjacksonsociety.org. 3 CONTENTS Foreword by Chris Bryant MP 5 About the Author 6 About the Russia Studies Centre 6 Acknowledgements 6 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 8 INTRODUCTION 11 CHAPTER -

PERSA Working Paper No. 37

Planning the Soviet Defense Industry: the Late 1920s and 1930s Andrei Markevich Moscow State University PERSA Working Paper No. 37 Political Department of Economics Economy Research in Soviet Archives Version: 7 November 2004 Available from www.warwick.ac.uk/go/persa. Planning the Soviet Defense Industry: the Late 1920s and 1930s* Andrei Markevich† Open Lyceum, All Russian External Multi-Disciplinary School, Moscow State University Abstract The paper describes the procedures for planning the Soviet defense industry in the interwar period and analyses its limitations. Three features differentiated the planning of the defense industry from that of the civilian economy. First, the supply of national defense in the broadest sense had high priority and received the close attention of the country’s top leadership. Second, the process of military and economic planning for defense that created the context of defense industry plans had a strongly forward-looking character and generated increasing demands through the interwar years. Third, the detailed planning of defense industry was carried on simultaneously in two separate bureaucracies, a military hierarchy preoccupied with formulating demands and an industrial hierarchy the task of which was to organize supply; planners made strenuous efforts to reconcile supplies and demands in the defense industry, and met with limited success. * This paper contributes to research on the political economy of the Soviet Union under Stalin funded by the Hoover Institution (principal investigator, Paul Gregory). † Thanks to Paul Gregory and Mark Harrison for advice and comments; I am responsible for remaining errors. Please address communications to Andrei Markevich care of [email protected]. -

Pro Hockey... Said

INSIDE:• Ukraine restricts imports of used cars — page 2. • Profiles of candidates for the Verkhovna Rada — page 3. • Wrap-up of Ukraine’s participation in the Winter Olympics — page 9. Published by the Ukrainian National Association Inc., a fraternal non-profit association Vol. LXVI HE KRAINIANNo. 9 THE UKRAINIAN WEEKLY SUNDAY, MARCH 1, 1998 EEKLY$1.25/$2 in Ukraine DemjanjukT regainsU U.S. citizenship Ukraine andW Russia initial by Roma Hadzewycz Trawniki findings.” economic cooperation pact He cited a November 1993 ruling in the PARSIPPANY, N.J. — John Demjanjuk extradition portion of the Demjanjuk case, by Roman Woronowycz countries,” said the Russian prime minis- has regained his U.S. citizenship, thanks to in which the 6th Circuit Court of Appeals Kyiv Press Bureau ter. a February 20 ruling by a federal judge who held that “the OSI attorneys acted with reversed Demjanjuk’s 1981 denaturaliza- Prime Minister Pustovoitenko said the reckless disregard for the truth and for the KYIV — Ukraine and Russia agreed pact addresses a wide array of aspects of tion, citing fraud on the part of U.S. govern- government’s obligation to take no steps to a 10-year comprehensive economic ment prosecutors. economic cooperation, including “cooper- that prevent an adversary from presenting cooperation pact on February 20 that ation in broadening trade markets, draft- Judge Paul R. Matia of the U.S. District his case fully and fairly. This was fraud on they hope will more than double trade Court for the Northern District of Ohio, ing of proposals to set up transnational the court in the circumstances of this case between the two neighbors by 2007. -

Gabinete Adjunto De Crisis KGB Guerra Fría

Gabinete Adjunto de Crisis KGB Guerra Fría 12 DE MARZO DE 1947 [email protected] Manual de Procedimientos COSMUN 2020 Manual de Procedimientos GAC Presidente: Gregorio Noreña Vice-Presidente: Ilana Garza 1. Página de portada 2. Cartas de la mesa 2.1. Carta del presidente 2.2. Carta del vice presidente 3. ¿Qué es un GAC? (Composición) 3.1. Gabinetes 3.2. Sala de crisis 3.3. Funcionamiento 4. Historia 4.1. Creación de la KGB 4.2. La KGB en el bloque socialista 4.3. Esctructura 5. La Guerra Fría 5.1. Introducción 5.2. Antecedentes históricos 5.3. Información general 5.4. Guerras subsidiarias 5.5. Final de la guerra 6. Situación Actual 6.1. (1947) 7. Cargos 7.1. Presidente del consejo de ministros de la Unión Soviética 2 7.2. Presidente del presidium del Soviet Supremo 7.3. Primer viceprimer ministro de la Unión Soviética (3) 7.4. Secretario general del partido comunista de la Unión Soviética 7.5. Director de la KGB 7.6. Ministro de relaciones exteriores de la Unión Soviética 7.7. Embajador de la Unión Soviética a los Estados Unidos 7.8. Representante permanente de la Unión Soviética ante las Naciones Unidas 7.9. Ministro de justicia de la Unión Soviética 8. Personajes importantes 8.1. Iósif Stalin 8.2. Nikita Jrushchov 8.3. Leonid Brézhnev 8.4. Nikolái Bulganin 8.5. Vasili Mitrojin 8.6. Albrecht Dittrich/Jack Barsky 8.7. Andrei Zhdanov 8.8. Mijail Gorbachov 8.9. Aleksei Kosyguin 8.10. Nikolai Podgorni 8.11. Konstantin Chernenko 8.12. -

Participants List for OECD Global Forum on Biotechnology

Participants List for OECD Global Forum on Biotechnology 12/11/2012 Ms. Johanna ADAMI M.D. Professor, Director and Head of Health Division Swedish Governmental Agency for Innovation Systems (Vinnova) Sweden Ms. Maarja ADOJAAN Chief Expert Research Policy Department Ministry of Education and Research (EDU) Estonia Mr. Aldo ALDAMA Mexican Delegate to the DAC Development, Employment, Health and Social Affairs Permanent Delegation of Mexico to the OECD France Ms. Jacqueline ALLAN Senior Policy Analyst (Biotechnology and Nanotechnology) STI/STP OECD Ms. Agnes ALLANSDOTTIR University of Siena Italy Mr. Alessandro ALLEGRA Bioethics United Nations Educational Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) France Mr. Mark BALE Deputy Director Health Science & Bioethics Department of Health United Kingdom Mr. Alexandre BARTSEV Consultant France Ms. Marie-Ange BAUCHER Policy Analyst (Nanotechnology) STI/STP OECD Ms. Dorothée BENOIT BROWAEYS Déléguée générale VivAgora France Ms. Isabella BERETTA Scientific Advisor International Cooperation State Secretariat for Education and Research SER Switzerland Mr. Steinar BERGSETH The Knowledge Based Bioeconomy Research Council Norway (RCN) Norway Miss Margo BERNELIN PhD Candidate Law Department Law department Univeristé Paris Ouest France Mr. Christopher BERRY Press and Communications Officer ESRC Genomics Policy and Research Forum Edinburgh United Kingdom Mr. Öyvind Johan BJÖRKMANN Senior Advisor Ministry of Trade and Industry Norway Mr. Roeland BOSCH Chief Economist Directorate Biobased Economy Ministry of Economic Affairs, Agriculture and Innovation Netherlands Mrs. Cecilia CERREDO- Secretariat WILLIAMSON STI/STP OECD France Ms. Claudio CHIAROLLA Research Fellow IDDRI France Mr. Yong-Kyung CHOE Director Bio-Therapeutics Res. Inst. Korea Research Institute of Bioscience & Biotechnology (KRIBB) Republic of Korea Mr. Michael CHRISTIANSEN Section Head Clinical Biochemistry, Immunology and Genetics Statens Serum Institut Denmark Ms. -

2 Explaining Political Transformation in the Soviet Union

Notes 2 Explaining Political Transformation in the Soviet Union 1‘O programme sotsial’nogo razvitiia sela’, Pravda (13 April 1989), 2. 2 Judith Pallot, ‘Rural Depopulation and the Restoration of the Russian Village under Gorbachev’, Soviet Studies, vol. 42, no. 4 (1990), 655–74. 3 Michael Cox, ed., Rethinking the Soviet Collapse: Sovietology, the Death of Communism and the New Russia (London: Pinter, 1998). 4 For a more nuanced account of the literature than space here allows see George Breslauer, ‘In Defense of Sovietology’, Post-Soviet Affairs, vol. 8, no. 3 (1992), 197–238. 5 Carl J. Friedrich and Zbigniew Brzezinski, Totalitarian Dictatorship and Autocracy (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1956) and the 2nd edition, revised by Friedrich (1965); Leonard Schapiro, Totalitarianism (London: Macmillan – now Palgrave Macmillan, 1972); Robert Borrowes, ‘Totalitarianism: the Revised Standard Version’, World Politics, XXI, no. 2 ( January 1969), 272–94; Carl. J. Friedrich, Michael Curtis, and Benjamin J. Barber, Totalitarianism in Perspective: Three Views (London: Pall Mall Press, 1969). 6 The most eloquent representative of the application of pluralist ideas to the Soviet Union was Jerry Hough with his notion of ‘institutional pluralism’. Jerry Hough, ‘The Soviet System: Petrification or Pluralism’, in The Soviet Union and Social Science Theory (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1977). Although Hough later came to disown this term, it received the qualified support of a number of other scholars: Peter Solomon, Soviet Criminologists and Criminal Policy: Specialists in Policy Making (London: Macmillan – now Palgrave Macmillan, 1978) and Stephen Fortescue, The Communist Party and Soviet Science (Basingstoke: Macmillan (now Palgrave Macmillan) in association with the Centre for Russian and East European Studies, University of Birmingham, 1986). -

Torn: the Story of a Lithuanian Migrant

Torn: the story of a Lithuanian migrant By Grazina Pranauskas MA, Faculty of Arts, Deakin University, Geelong. BA (Hons), Faculty of Arts, Deakin University, Geelong. BA, Major Studies in Journalism Studies and Literary Studies, Faculty of Arts, Deakin University, Geelong. BMus. in Choral Conducting, Conservatorium of Music, Vilnius, Lithuania. Submitted in fulfillment of the requirements for the Doctor of Philosophy, College of Arts, Victoria University, Melbourne, 24 November 2014. Abstract This doctorate consists of two parts: a novel Torn and the exegesis: Writing the migrant story: nostalgia, identity and belonging. The novel and theoretical exegesis are intended to complement each other in capturing the 20th century Lithuanian historical and political circumstances that led to Lithuanian emigration to Australia. In my novel and exegesis, my intention has been to explore how the experiences of Lithuanian refugees and migrants differ, especially in relation to nostalgia, identity and belonging, depending on the time and circumstances of their arrival in Australia. Lithuanians came to Australia from the same place geographically, but from a different place in terms of history and politics. My novel is a creative representation of the Lithuanian migrants’ experience in the diaspora. It is set in the 1980s and 90s when the political, socio-economic and cultural environment radically shifted under Mikhail Gorbachev’s policy of perestroika (restructure). Daina, a theatre producer from Soviet Lithuania, comes to Australia to look after her great-uncle, Algis. As a postwar Lithuanian refugee, settled here since the 1940s, Algis has strong views about his Soviet-occupied homeland and its people. He lets Daina know that he hates anything associated with Russia and Russians who, in his opinion, were responsible for killings and deportations of Lithuanians during the war.