Application of Semantic Technology to Define Names for Fungi by Nathan Wilson1, Kathryn M

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Toxic Fungi of Western North America

Toxic Fungi of Western North America by Thomas J. Duffy, MD Published by MykoWeb (www.mykoweb.com) March, 2008 (Web) August, 2008 (PDF) 2 Toxic Fungi of Western North America Copyright © 2008 by Thomas J. Duffy & Michael G. Wood Toxic Fungi of Western North America 3 Contents Introductory Material ........................................................................................... 7 Dedication ............................................................................................................... 7 Preface .................................................................................................................... 7 Acknowledgements ................................................................................................. 7 An Introduction to Mushrooms & Mushroom Poisoning .............................. 9 Introduction and collection of specimens .............................................................. 9 General overview of mushroom poisonings ......................................................... 10 Ecology and general anatomy of fungi ................................................................ 11 Description and habitat of Amanita phalloides and Amanita ocreata .............. 14 History of Amanita ocreata and Amanita phalloides in the West ..................... 18 The classical history of Amanita phalloides and related species ....................... 20 Mushroom poisoning case registry ...................................................................... 21 “Look-Alike” mushrooms ..................................................................................... -

MUSHROOMS of the OTTAWA NATIONAL FOREST Compiled By

MUSHROOMS OF THE OTTAWA NATIONAL FOREST Compiled by Dana L. Richter, School of Forest Resources and Environmental Science, Michigan Technological University, Houghton, MI for Ottawa National Forest, Ironwood, MI March, 2011 Introduction There are many thousands of fungi in the Ottawa National Forest filling every possible niche imaginable. A remarkable feature of the fungi is that they are ubiquitous! The mushroom is the large spore-producing structure made by certain fungi. Only a relatively small number of all the fungi in the Ottawa forest ecosystem make mushrooms. Some are distinctive and easily identifiable, while others are cryptic and require microscopic and chemical analyses to accurately name. This is a list of some of the most common and obvious mushrooms that can be found in the Ottawa National Forest, including a few that are uncommon or relatively rare. The mushrooms considered here are within the phyla Ascomycetes – the morel and cup fungi, and Basidiomycetes – the toadstool and shelf-like fungi. There are perhaps 2000 to 3000 mushrooms in the Ottawa, and this is simply a guess, since many species have yet to be discovered or named. This number is based on lists of fungi compiled in areas such as the Huron Mountains of northern Michigan (Richter 2008) and in the state of Wisconsin (Parker 2006). The list contains 227 species from several authoritative sources and from the author’s experience teaching, studying and collecting mushrooms in the northern Great Lakes States for the past thirty years. Although comments on edibility of certain species are given, the author neither endorses nor encourages the eating of wild mushrooms except with extreme caution and with the awareness that some mushrooms may cause life-threatening illness or even death. -

Fall 2012 Species List Annex October 2012 Lummi Island Foray Species List

MushRumors The Newsletter of the Northwest Mushroomers Association Volume 23, Issue 2 Summer - Fall, 2012 Record 88 Days Without Measurable Precipitation Defines Northwest Washington’s 2012 Mushroom Season As June had faded into the first week of July, after a second consecutive year of far above average rainfall, no one could have anticipated that by the end of the second week of July we would see virtually no more rain until October 13th, only days before the Northwest Mushroomer’s Association annual Fall Mushroom Show. The early part of the season had offered up bumper crops of the prince (Agaricus augustus), and, a bit later, similar Photo by Jack Waytz quantities of the sulphur shelf (Laetiporus coniferarum). There were also some anomalous fruitings, which seemed completely inexplicable, such as matsutake mushrooms found in June and an exquisite fruiting of Boletus edulis var. grand edulis in Mt. Vernon at the end of the first week of July, under birch, (Pictured on page 2 of this letter) and Erin Moore ran across the king at the Nooksack in Deming, under western hemlock! As was the case last year, there was a very robust fruiting of lobster mushrooms in advance of the rains. It would seem that they need little, or no moisture at all, to have significant flushes. Apparently, a combination of other conditions, which remain hidden from the 3 princes, 3 pounds! mushroom hunters, herald their awakening. The effects of the sudden drought were predictably profound on the mycological landscape. I ventured out to Baker Lake on September 30th, and to my dismay, the luxuriant carpet of moss which normally supports a myriad of Photo by Jack Waytz species had the feel of astro turf, and I found not a single mushroom there, of any species. -

Catalogue of Fungus Fair

Oakland Museum, 6-7 December 2003 Mycological Society of San Francisco Catalogue of Fungus Fair Introduction ......................................................................................................................2 History ..............................................................................................................................3 Statistics ...........................................................................................................................4 Total collections (excluding "sp.") Numbers of species by multiplicity of collections (excluding "sp.") Numbers of taxa by genus (excluding "sp.") Common names ................................................................................................................6 New names or names not recently recorded .................................................................7 Numbers of field labels from tables Species found - listed by name .......................................................................................8 Species found - listed by multiplicity on forays ..........................................................13 Forays ranked by numbers of species .........................................................................16 Larger forays ranked by proportion of unique species ...............................................17 Species found - by county and by foray ......................................................................18 Field and Display Label examples ................................................................................27 -

SOMA Speaker: Catharine Adams March 17 at the Sonoma County Farm Bureau “How the Death Cap Mushroom Conquered the World”

SOMANEWS From the Sonoma County Mycological Association VOLUME 28: 7 MARCH 2016 SOMA Speaker: Catharine Adams March 17 At the Sonoma County Farm Bureau “How the Death Cap Mushroom Conquered the World” Cat Adams is interested in how chemical ecology in- fluences interactions between plants and fungi. For her PhD in Tom Bruns’ lab, Cat is studying the inva- sive ectomycorrhizal fungus, Amanita phalloides. The death cap mushroom kills more people than any oth- er mushroom, but how the deadly amatoxins influ- ence its invasion remains unexplored. Previously, Cat earned her M.A. with Anne Pringle at Harvard University. Her thesis examined fungal pathogens of the wild Bolivian chili pepper, Capsi- cum chacoense, and how the fungi evolved tolerance to spice. With the Joint Genome Institute, she is now sequencing the genome of one fungal isolate, a Pho- mopsis species, to better understand the novel en- zymes these fungi wield to outwit their plant host. She also collaborates with a group in China, study- loides, was an invasive species, and why we should ing how arbuscular mycorrhizae can help crop plants care. She’ll then tell you about 10 years of research at avoid toxic effects from pollution. Their first paper is Pt Reyes National Seashore examining how Amanita published in Chemosphere. phalloides spreads. Lastly, Cat will outline her ongo- At the SOMA meeting, Cat will explain how scientists ing work to determine the ecological role of Phalloi- determined the death cap mushroom, Amanita phal- des’ toxins, and will present her preliminary findings. NEED EMERGENCY MUSHROOM POISONING ID? After seeking medical attention, contact Darvin DeShazer for identification at (707) 829- 0596. -

Monograph of Chroogomphus (Gomphidiaceae) 1

This file was created by scanning the printed publication. Errors identified by the software have been corrected; however, some errors may remain. MONOGRAPH OF CHROOGOMPHUS (GOMPHIDIACEAE) 1 ORSON K. MILLER, }R.2 (WITH 6 FIGURES) The study of the interesting agaric family, Gomphidiaceae, was un dertaken in 1958. Since that time collections have been made and examined from Idaho, Washington, Oregon, Montana, and the Upper and Lower Peninsulas of Michigan. Collections from New Hampshire failed to yield any specimens in this genus. All but three of the North American species have been studied from fresh material. In addition, the help of Dave Largent in sending fresh material via air mail from California is acknowledged. A large number of collections of dried material were examined at the University of Michigan Herbarium. Notes and photographs at the University of Michigan Herbarium by C. H. Kauffman and A. H. Smith were made available and invaluable assistance was given by Dr. Smith during the course of this study. I am also indebted to the curators of the following herbaria for the loan of or permission to study material which greatly aided in this study: Naturhistoriska Riksmuseet, Stockholm, Sweden; New York State Mu seum, Albany; New York Botanical Garden; Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew; and the Farlow Herbarium, Harvard University. Singer (1949, 1951, 1962) includes two genera in the Gomphidiaceae, namely Gomphidius and Cystogomphus. C:,,stogomphus is a monotypic genus. The remaining species in the family are classified under three subgenera within Gomphidius. These are Chroogomphus, Laricogom phus, and Gomphidius. Smith and Dreisinger ( 1954) found that a number of species in Gomphidius contain amyloid (dark blue to violet) tramal hyphae when mounted in Melzer's solution. -

Systematics of the Genus Rhizopogon Inferred from Nuclear Ribosomal DNA Large Subunit and Internal Transcribed Spacer Sequences

AN ABSTRACT OF THE THESIS OF Lisa C. Grubisha for the degree of Master of Science in Botany and Plant Pathology presented on June 22, 1998. Title: Systematics of the Genus Rhizopogon Inferred from Nuclear Ribosomal DNA Large Subunit and Internal Transcribed Spacer Sequences. Abstract approved Redacted for Privacy Joseph W. Spatafora Rhizopogon is a hypogeous fungal genus that forms ectomycorrhizae with genera of the Pinaceae. The greatest number and species of Rhizopogon are found in coniferous forests of the Pacific Northwestern United States, where members of the Pinaceae are also concentrated. Rhizopogon spp. are host-specific primarily with Pinus spp. and Pseudotsuga spp. and thus are an important component of these forest ecosystems. Rhizopogon includes over 100 species; however, the systematics of Rhizopogon have not been well understood. Currently the genus is placed in the Boletales, an order of ectomycorrhizal fungi that are primarily epigeous and have a tubular hymenium. Suillus is a stipitate genus closely related to Rhizopogon that is also in the Boletales and host specific with Pinaceae.I examined the relationship of Rhizopogon to Suillus and other genera in the Boletales. Infrageneric relationships in Rhizopogon were also investigated to test current taxonomic hypotheses and species concepts. Through phylogenetic analyses of large subunit and internal transcribed spacer nuclear ribosomal DNA sequences, I found that Rhizopogon and Suillus formed distinct monophyletic groups. Rhizopogon was composed of four distinct groups; sections Amylopogon and Villosuli were strongly supported monophyletic groups. Section Rhizopogon was not monophyletic, and formed two distinct clades. Section Fulviglebae formed a strongly supported group within section Villosuli. -

The Ecology of the Macrofungi

THE ECOLOGY OF THE MACROFUNGI AT THE LANPHERE-CHRISTENSEN DUNES PRESERVE, ARCATA, CALIFORNIA by Sue Sweet Van Hook A Thesis Presented to The Faculty of Humboldt State University In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts December, 1985 THE ECOLOGY OF THE MACROFUNGI AT THE LANPHERE-CHRISTENSEN DUNES PRESERVE ARCATA, CALIFORNIA by Sue Sweet Van Hook We certify that we have read this study and that it conforms to acceptable standards of scholarly presentation and is fully adequate, in scope and quality, as a thesis for the degree of Master of Arts. Major Professor V 1 Y Approved by the Graduate Dean Acknowledgements I wish to thank Dr. David L. Largent, my major professor and mentor, for years of excellent guidance and encouragement in the field of mycology; the members of my graduate committee, Drs. Dennis Anderson, Francis Meredith, and Richard Hurley, for their critical review of the thesis; mycologists, Dr. Orson K. Miller, Dr. Joseph F. Ammirati, and Dr. Harry D. Theirs, for their verification of species identifications; Hortense M. Lanphere for the background material on the fungi at the preserve and for her supportive correspondence; Marjorie Moore for data entry and graphics; The Nature Conservancy, for permitting the study at the Lanphere-Cristensen Dunes Preserve; and my family for their labor, love and patience. Table of Contents Page I. Introduction A. Literature review 1 B. Objectives 5 II. The Study Area A. Location 6 B. Geology 6 C. Climate 8 D. Plant Communities 9 III. Methods and Materials A. Areas studied 10 B. Plots within areas 16 C. -

Chroogomphus Vinicolor • Chroogomphus Rutilus • Chroogomphus Ochraceus

Application of Semantic Technology to Define Names for Fungi Nathan Wilson Tuesday, July 17, 12 Who am I? • Naturalist • Mycologist • Software Professional • Director of Biodiversity Informatics for EOL • Director of the MBL Center for Library and Informatics Tuesday, July 17, 12 Mushroom Observer http://mushroomobserver.org/ Tuesday, July 17, 12 Linnaeus, We Have a Problem! • Cryptic Species • Paraphyletic & Polyphyletic Groups • Convergent Evolution • Changing Circumscriptions Tuesday, July 17, 12 Cryptic Species Tuesday, July 17, 12 Who spiked the pine? Tuesday, July 17, 12 Candidates • Pine Spike • Chroogomphus vinicolor • Chroogomphus rutilus • Chroogomphus ochraceus Tuesday, July 17, 12 Chroogomphus vinicolor Tuesday, July 17, 12 Para/Polyphyly Tuesday, July 17, 12 What’s white or red and spicy!? © Nathan Wilson © Dimitar Bojantchev © Oluna & Adolf Ceska Tuesday, July 17, 12 Convergent Evolution Tuesday, July 17, 12 Who likes truffles? © Noah Siegel © Mary Smiley © Daniel B. Wheeler © Nathan Wilson © Oluna & Adolf Ceska Tuesday, July 17, 12 Gasteromycetes anyone? © Nathan Wilson © Noah Siegel Tuesday, July 17, 12 Changing Circumscriptions Tuesday, July 17, 12 Definition of a Scientific Name Reference Latin name Type Circumscription Cap: 2-10cm wide; usually overlapping or in a row or a rosette; kidney shaped, also described as fan shaped, sometimes fused laterally; can be flat to wavy; multicolored concentric zoning on the upper surface; zones alternate between Tuesday, July 17, 12 Definition of a Scientific Name Reference Latin name Type -

Hericium Ramosum - Comb’S Tooth Fungi

2005 No. 4 Hericium ramosum - comb’s tooth fungi This year we have been featuring the finalists of the “Pick a Wild Mushroom, Alberta!” project. Although the winner was the Leccinum boreale all the finalists are excellent edibles which show the variety of mushroom shapes common in Alberta. If all you learned were these three finalists and the ever popular morel you would have a useable harvest every year. The taste and medicinal qualities of each is very different so you not only have variety in shape and location but in taste and value as well. If you learn about various edible species and hunt for harvest you will become a mycophagist. Although you won’t need four years of university to get this designation, you will find that over the lifetime of learning about and harvesting mushroom you will put in more time than the average Hericium ramosum is a delicately flavoured fungi that is easily recognized and has medicinal university student and probably properties as well. Photo courtesy: Loretta Puckrin. enjoy it much more. edible as well. With their white moments of rapt viewing before the Although often shy and hard fruiting bodies against the dark picking begins. People to find, this delicious fungus family trunks of trees, this fungus is knowledgeable in the medicinal is a favourite of new mushroom easily spotted and often produces pickers as all the ‘look alikes’ are (The Hericium ...continued on page 3) FEATURE PRESIDENT’S PAST EVENTS NAMA FORAY & UPCOMING MUSHROOM MESSAGE Lambert Creek ... pg 5 CONFERENCE EVENTS The Hericium It has been a .. -

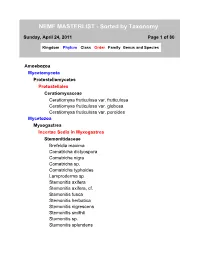

NEMF MASTERLIST - Sorted by Taxonomy

NEMF MASTERLIST - Sorted by Taxonomy Sunday, April 24, 2011 Page 1 of 80 Kingdom Phylum Class Order Family Genus and Species Amoebozoa Mycetomycota Protosteliomycetes Protosteliales Ceratiomyxaceae Ceratiomyxa fruticulosa var. fruticulosa Ceratiomyxa fruticulosa var. globosa Ceratiomyxa fruticulosa var. poroides Mycetozoa Myxogastrea Incertae Sedis in Myxogastrea Stemonitidaceae Brefeldia maxima Comatricha dictyospora Comatricha nigra Comatricha sp. Comatricha typhoides Lamproderma sp. Stemonitis axifera Stemonitis axifera, cf. Stemonitis fusca Stemonitis herbatica Stemonitis nigrescens Stemonitis smithii Stemonitis sp. Stemonitis splendens Fungus Ascomycota Ascomycetes Boliniales Boliniaceae Camarops petersii Capnodiales Capnodiaceae Capnodium tiliae Diaporthales Valsaceae Cryphonectria parasitica Valsaria peckii Elaphomycetales Elaphomycetaceae Elaphomyces granulatus Elaphomyces muricatus Elaphomyces sp. Erysiphales Erysiphaceae Erysiphe polygoni Microsphaera alni Microsphaera alphitoides Microsphaera penicillata Uncinula sp. Halosphaeriales Halosphaeriaceae Cerioporiopsis pannocintus Hysteriales Hysteriaceae Glonium stellatum Hysterium angustatum Micothyriales Microthyriaceae Microthyrium sp. Mycocaliciales Mycocaliciaceae Phaeocalicium polyporaeum Ostropales Graphidaceae Graphis scripta Stictidaceae Cryptodiscus sp. 1 Peltigerales Collemataceae Leptogium cyanescens Peltigeraceae Peltigera canina Peltigera evansiana Peltigera horizontalis Peltigera membranacea Peltigera praetextala Pertusariales Icmadophilaceae Dibaeis baeomyces Pezizales -

Anthony Lakes Fungi Forays: 2011 Wallowa-Whitman National Forest Interagency Special Status and Sensitive Species Program Final Report, October 28, 2011

Figure 1 Anthony Lakes Fungi Forays: 2011 Wallowa-Whitman National Forest Interagency Special Status and Sensitive Species Program Final Report, October 28, 2011 Jenifer Ferriel Wallowa-Whitman National Forest, 1550 Dewey Ave., Baker City, OR 541-523-1362, [email protected] Introduction The 2011 surveys at Anthony Lakes in the Elkhorn Mountains northwest of Baker City, Oregon were a continuation of Brooks’ 2009 ISSSSP project. The 2009 project hosted a fall foray in a volunteer partnership with Southern Idaho Mycological Association at Anthony Lakes, in addition to developing a working list of potentially rare fungi for the Blue Mountain Area, including any available information on the ecology and occurrences of the rare or under- collected fungi. The 2009 working list was developed with the idea that after adequate field investigation, some of the species might be recommended to be added to the ORBIC list. The reason for multiple forays in the same area was to add more species to the overall species list for the Anthony Lakes area, possibly detecting some of the species on the 2009 working list of rare or under-collected species. Multi-year, multi-season surveys span a greater range of climatic conditions and are recommended to increase the probability of detecting resident fungi (USDA USFS and USDI BLM, 2008), hence the early summer and fall forays in 2011. The 2011 project consisted of early summer and fall forays, using the same volunteer cooperator in the same vicinity as the 2009 fall foray. The goals of the 2011 surveys were to continue the field investigations initiated in 2009, increase the number of species found in the area, continue to collect information on the ecology of fungi in the Elkhorn Mountains, and continue the relationship between SIMA volunteers and the Wallowa-Whitman National Forest.