16Moretti V2 Ch16 274-294.Qxd

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

La Fuerza Del Sino Romántico En Don Álvaro, Hernani Y Antony

LA FUERZA DEL SINO ROMÁNTICO EN DON ÁLVARO, HERNANI Y ANTONY M.a Mercedes Guirao Silvente Correo electrónico: [email protected] Resumen Muchos críticos románticos se esforzaron en alejar Don Álvaro o la fuerza del sino de los dos dramas franceses que le sirvieron de modelos indirectos: Hernani de Victor Hugo y Antony de Alexandre Dumas, por considerarlos corruptos e inmorales. Pero no hay que olvidar que la obra de Rivas fue gestada en Francia, durante el exilio del autor; en pleno contacto con la revolución liberal y romántica en Europa. Este artículo pretende, a través de un estudio comparativo entre estos tres dramas fundamentales del Romanticismo europeo, demostrar su estrecha relación. Las tres obras sorprenden por la fuerza de ese destino nefasto, causante de desgracia y muerte, que está directamente vinculado con la schicksalstragödie alemana y evidencian la superación de la vieja y rígida frontera entre Orden y Caos; entre lo Apolíneo y lo Dionisíaco. Palabras clave: drama romántico, Don Álvaro o la fuerza del sino, Hernani, Antony. THE FORCE OF THE ROMANTIC FATE IN DON ÁLVARO, HERNANI AND ANTONY Abstract 237 Many romantic critics strove to separate Don Álvaro or the force of the fate from the two French dramas which served as indirect models: Victor Hugo’s Hernani and Alexandre Dumas’ Antony, for considering them corrupt and immoral. But it should not be forgotten that Rivas’ play was conceived in France, during the exile of the author; in full contact with the liberal and romantic revolution in Europe. This article aims, through a comparative study of these three fundamental dramas of European romanticism, to demonstrate their close relationship. -

› Le Roi S' Amuse ‹ Und › Rigoletto

GIUSEPPE VERDI RIGOLETTO OPER IN DREI AUFZÜGEN LIBRETTO VON NACH DEM DRAMA ›LE ROI S’AMUSE FRANCESCO MARIA PIAVE VON VICTOR HUGO ‹ PREMIERE 28. JUNI 2015 MUSIKALISCHE LEITUNG: SYLVAIN CAMBRELING REGIE: JOSSI WIELER, SERGIO MORABITO BÜHNE: BERT NEUMANN KOSTÜME: NINA VON MECHOW LICHT: LOTHAR BAUMGARTE CHOR: JOHANNES KNECHT ← HANDLUNG › LE ROI S’ AMUSE ‹ UND › RIGOLETTO ‹ – DRAMATURGIE DES BÜHNENRAUMS BRUNO FORMENT 16 Wir befinden uns am Stadtrand Mantuas im 16. Jahrhundert, am »öden Ufer des Mincio«. Im »halbverfallenen« Haus des Auftragskillers Sparafucile ereignet sich tief in der Nacht ein Drama. Im Parterre stimmt der Herzog von Mantua ein Loblied auf die Reize Maddalenas, der Schwester des Hausherrn, an (»Bella figlia dell’amore« – »Schöne Tochter der Liebe«); ihr Lachen gibt ihm Antwort (»Ah! Ah! rido ben di core« – »Ha, ha, ich lache recht von Herzen«). Vor der Ein- gangstür belauscht Gilda die Unterhaltung. Die Treulosigkeit des Herzogs stürzt sie in Verzweiflung: Sie glaubte sich von ihm geliebt (»Ah così parlar d’amore / a me pur l’infame ho udito« – »Ach, so habe ich den Schändlichen auch zu mir von Liebe sprechen hören«). Gildas Vater, der Hofnarr Rigoletto, will sie mit dem Versprechen trösten, sie zu rächen (»Taci, il piangere non vale« – »Schweig, Weinen nützt nichts«). Wie wir wissen, ist sein Racheplan die Ursache einer grauenvollen Verwechslung, die Gildas Tod herbeiführen wird. Das Quartett »Un dì, se ben rammentomi« (»Einst, wenn ich mich recht erinnere«) im dritten Akt von Rigoletto (1851) gilt als ein Höhepunkt von Verdis Ensemble- kunst: In mitreißender Vereinigung von musikalischer Dramatik und Theater- spiel verleiht es den Absichten und Gefühlen von vier Individuen simultan Aus- druck. -

John Dewey, Maria Montessori, and Objectivist Educational Philosophy During the Postwar Years

73 Historical Studies in Education / Revue d’histoire de l’éducation ARTICLES / ARTICLES “The Ayn Rand School for Tots”: John Dewey, Maria Montessori, and Objectivist Educational Philosophy during the Postwar Years Jason Reid ABSTRACT Objectivism, the libertarian philosophy established by Ayn Rand during the postwar years, has attracted a great deal of attention from philosophers, political scientists, economists, and English professors alike in recent years, but has not received much notice from historians with an interest in education. This article will address that problem by discussing how Rand and her followers established a philosophy of education during the 1960s and 1970s that was based, in part, on vilifying the so-called collectivist ideas of John Dewey and lionizing the so-called individualist ideas of Maria Montessori. Unfortunately, the narrative that emerged during this time seriously misrepresented the ideas of both Dewey and Montessori, resulting in a some- what distorted view of both educators. RÉSUMÉ L’objectivisme, philosophie libertaire conçue par Ayn Rand dans la période de l’après-guerre, a suscitée beaucoup d’attention de la part des philosophes, politologues, économistes et profes- seurs de littérature anglaise, mais rien de tel chez les historiens de l’éducation. Cet article cor- rige cette lacune, en montrant comment durant les années 1960 et 1970 Rand et ses partisans ont établi une philosophie de l’éducation qui s’appuyait, en partie, sur la diffamation des idées prétendues collectivistes de John Dewey et l’idolâtrie de l’individualisme de Maria Montessori. Malheureusement, leurs travaux ont donné une fausse image des idées de Dewey et Montessori et conséquemment ont déformé les théories ces deux éducateurs. -

Comprachicos John Boynton Kaiser

Journal of Criminal Law and Criminology Volume 4 | Issue 2 Article 8 1913 Comprachicos John Boynton Kaiser Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarlycommons.law.northwestern.edu/jclc Part of the Criminal Law Commons, Criminology Commons, and the Criminology and Criminal Justice Commons Recommended Citation John Boynton Kaiser, Comprachicos, 4 J. Am. Inst. Crim. L. & Criminology 247 (May 1913 to March 1914) This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Northwestern University School of Law Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Criminal Law and Criminology by an authorized editor of Northwestern University School of Law Scholarly Commons. THE COMPRACHICOS. JVOE BOYNTON KAISER.' The fertile brain of Victor Hugo-novelist, dramatist, poet, states- man, and sociologist-has given the world numerous studies in criminal sociology which, for human interest, will ever remain classic. Less classic and less well known than many of these studies, yet strangely combining fact and fiction is the second of the two preliminary chapters to L'Homma. Qui Bit wherein Hugo describes at length a people whom he calls by the Spanish compound word Comprachicos, signifying child-buyers. It is a chronicle of crimes and punishments in which strange history is written and cruel and forgotten laws recall to mind ages long since past. Much condensed, though freely employing his own language, Hugo's description of the Comprachicos is given here; the language of no other will suffice. The Comprachicos, or Comprapequefios, were a hideous and nondescript association of wanderers, famous in the 17th century, forgotten in the 18th, unheard of in the 19th. -

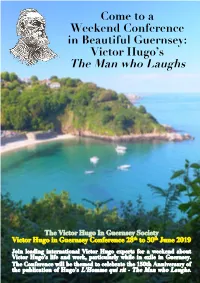

Victor Hugo's the Man Who Laughs

Come to a Weekend Conference in Beautiful Guernsey: Victor Hugo’s The Man who Laughs The Victor Hugo In Guernsey Society Victor Hugo in Guernsey Conference 28th to 30th June 2019 Join leading international Victor Hugo experts for a weekend about Victor Hugo’s life and work, particularly while in exile in Guernsey. The Conference will be themed to celebrate the 150th Anniversary of the publication of Hugo’s L’Homme qui rit - The Man who Laughs. th Victor Hugo Saturday 29 June In Guernsey 9:00 CONFERENCE registration in the Harry Bound Room at Les Côtils Centre. 2019 9:30 BEAUTIFUL INSIDE & OUT, by GÉRARD AUDINET ‘Beautiful inside and out.’ Does the soul have a face? We are all familiar A with the concept of ‘inner beauty,’ but how do artists approach the problem of Conference with L’Homme Qui Rit depicting it? This illustrated talk will reflect on the representations of ugliness Supported by the Guernsey 28th to 30th June and beauty in later arts and media of Victor Hugo’s ‘The Man who Laughs.’ Arts The Victor Hugo In Guernsey Society Commission 10:30 Break for discussion, Coffee or tea. The Victor Hugo In Guernsey Society 11:00 JUSTICE IN THE MAN WHO LAUGHS, by MYRIAM ROMAN Victor Hugo in Guernsey 2019 Conference The representation of justice in ‘The Man who Laughs’ passes through a series of 28th to 30th June 2019 images and myths. The singularity of this novel seems to be to ask the last question of a possible divine injustice through a series of metaphors that project, on the PROGRAMME cosmos, terrifying images of the process and the punishment. -

Les Mis Education Background.Indd

ABOUT VICTOR HUGO Victor was an excellent student who During the next 15 years he excelled in mathematics, physics, produced six plays, four volumes philosophy, French literature, Latin, of verse, and the romantic historical and Greek. He won fi rst place in a novel The Hunchback of Notre national poetry contest when he was 17. Dame, establishing his reputation as As a teenager, he fell in love with the greatest writer in France. a neighbour’s daughter, Adele Foucher. However, his mother In 1831, Adele Hugo became discouraged the romance, believing romantically involved with a well that her son should marry into a known critic and good friend of fi ner family. When his mother died Victor’s named Sainte-Beuve. Victor in 1821, Victor refused to accept became involved with the actress fi nancial help from his father. He Juliette Drouet, who became his lived in abject poverty for a year, but mistress in 1833. Supported by a then won a pension of 1,000 francs small pension from Hugo, Drouet a year from Louis XVIII for his fi rst became his unpaid secretary and volume of verse. Barely out of his travelling companion for the next teens, Hugo became a hero to the fi fty years. common people as well as a favourite of heads of state. Throughout his After losing one of his daughters lifetime, he played a major role in in a drowning accident and VICTOR HUGO’S enormously France’s political evolution from experiencing the failure of his successful career covered most of dictatorship to democracy. -

‚Ernani' Und ‚Hernani'

ULRICH SCHULZ-BUSCHHAUS Das Aufsatzwerk Institut für Romanistik | Karl-Franzens-Universität Graz Permalink: http://gams.uni-graz.at/o:usb-065-156 ‚Ernani‘ und ‚Hernani‘ Zum ‚Familialismus‘ der verdischen Oper Nicht immer, aber häufig handelt es sich bei Opernlibretti um gewissermaßen potenzierte Übersetzungen, die einerseits den Abstand zwischen verschiedenen Nationalliteraturen, andererseits jenen zwischen verschiedenen Genera überwinden müssen. Deshalb sind sie noch weniger als einfache Übersetzungen allein nach dem Kriterium der ‚Treue‘ zum Original zu bewerten: ja die Gestalt der ‚belle infidèle‘ kann hier durchaus zur Regel werden, und je treuloser sich der Übersetzungstext von seiner dramatischen oder (seltener) romanesken Vorlage entfernt, um so schöner fällt oft das ‚Gesamtkunstwerk‘ aus, an dem das Libretto als bloße Komponente neben anderen Anteil hat. Opernlibretti mit den literarischen Werken, durch die sie inspiriert wurden, zu vergleichen, bildet daher im allgemeinen eine Übung von begrenztem Erkenntniswert, zumal wenn die Wahrnehmung 1 der unvermeidlichen Differenzen unter dem Gesichtspunkt ästhetischer Defekte erfolgt. Allzu verschiedenartig wirken die semiotischen Prämissen der Vergleichsgrößen. als daß ihr von vornherein evidenter Kontrast wirklich spezifische Auskünfte versprechen könnte. Nur wo in Sonderfällen Libretto und Vorlage, Übersetzungstext und übersetzter Text, historisch wie generisch nahe beieinander liegen, mag man aus dem konstrastiven Vergleich die Kennzeichnung von Merkmalen gewinnen, welche einem Blick auf das jeweilige Einzelwerk nicht ohne weiteres manifest werden. Sonderfälle solcher Art sind etwa jene Verdischen Opern, die sich der Sujets von mehr oder weniger rezenten romantischen Dramen bedienen. Dabei denke ich in erster Linie an die Stoffe, die Verdi und sein venezianischer Librettist Francesco Maria Piave dem Theater Victor Hugos entlehnt haben. Hier bleibt zunächst die historische Distanz – zwischen Hernani (1830) und Ernani (1844), Le Roi s’amuse (1832) und Rigoletto (1851) – verhältnismäßig gering. -

How Do You Solve a Problem Like Cosette? Femininity and the Changing Face of Victor Hugo’S Alouette

Stephens, B 2019 How Do You Solve a Problem Like Cosette? Femininity and the Changing Face of Victor Hugo’s Alouette. Modern Languages Open, 2019(1): 5 pp. 1–28. DOI: https://doi.org/10.3828/mlo.v0i0.253 ARTICLE How Do You Solve a Problem Like Cosette? Femininity and the Changing Face of Victor Hugo’s Alouette Bradley Stephens University of Bristol, GB [email protected] This article opens a new dialogue between French literature, gender studies, and adaptation studies by examining the conception and reception of the character of Cosette from Victor Hugo’s bestseller Les Misérables (1862). Adaptation studies has increasingly theorized the comparative rather than simply evaluative use of fidelity, in part encouraged by the ongoing push beyond the customary adaptive media of film. However, there has been little development of this methodology to ask how the relationship between literary works and their adaptations might help to nuance – if not revise – the masculinist notoriety of canonical male writers such as Hugo. Cosette provides an apt test case. She is the modern face of Les Misérables thanks to the hugely popular Boublil and Schönberg musical version (1985) and its trademark logo, which is based on Émile Bayard’s wistful 1879 illustration of her. Cosette’s poster-child status is deeply problematic but has never been explored. Her objectification as the ingenuous alouette (‘lark’) and her rags-to-riches tale tout a conservatism that is at once in line with Hugo’s patri- archal renown as a grand homme and yet at odds with Les Misérables’s reputation for progressive ideals. -

Views of 1 If E Str U~Gl Ing for Expression

TYPES OF HEROINES IN THID ~RENCH ROMANTIC DRAMA: A COMPARISON WITH THE H~ROINES OF RACINE AND CORNEILLE • .A Thesis Presented for the Degree of Master of Arts BY Della Roggers Maidox, B. A. -- - . - - ... - - -- --.. - - ....... ·- ~ ;.: ~ ;~;~;-~~~.~-:~ - - - - - - - - -- - - - .. ... .. - THE OHIO-STATE UNIVERSITY -- 19 :20 BIBLIOGRAPHY I. French Sources Histoire da la Langue et ]e la Litterature Fran9aise Vols. IV, V, and VII Petit de Julleville. Drama Ancien, Drame Moderne Emile Faguet. Les 3rands Maitres du XVII~ Siecle, Vol V, IDmile Faguet. Histoire de la Litterature Fran9aise Brunetiere. Le Mouvement Litt~raire ju XIX! Sihcle t'ellissier. Le Rialisme iu Ro~a~ti3me Pellissier. Histoire ie la Litterature Fran9aise Abr Y..1 A11 Uc et Crou z;et Les Epoques iu Theatre Fran9ais• Bruneti~re~ Les Jranis Eorivains 'ran9ais~~Raoine .Justave Larroumet. " II " " Boilea11 Lanson. Histoire iu Romantisme Th6o~hile Gautier. ld(es et Doctrines Litteraires du XrII' Siecle Vial et Denise. n " II II " XIX ' ti Vial et Denise. Histoire de la Litt~rature Fran9aise, Vols.II,III " " " " " Lanson. Portraits Litteraires, Vol I Sainte-Beuve. CauserEes de Lunii Sainte-Beuve. De La Poesie Dramatique, Belles Lettres, Vol. VII Diderot. L'Art Poetique Boi l'eau. Racine et Victor Hugo P. Stapfer. La Poetique de Racine Robert. Les Granis IDcrivains Fran9ais--Alex. Dumas,P~re Parigot. II. English Sources Rousseau and Romanticism Irving Babbitt. Literature of the French Renaissance, Vols. I and II Tilley. Annals of the· French Stage, Vols. II ani III Hawkins. The Romantic Revolt Vaughan. The Romantic Triumph Omond. Studies in Hugo's Dramatic Characters Bruner. Main Currents of Nineteenth Century Literature, Vol.III Brandes~ History of English Romanticism in the Nineteenth Century Beers. -

Works of Victor Hugo Volume 5

// S^i^* ^EUNHARDT declaiming "the battle of HEKNANI" BEFOUE the bust of victor HUGO. • « Ilernani, Frontispiece. ^ DRAMATIC WORKS ,,OF VICTOR^'* HUCau c * TBANSLATED BY FREDERICK L. SLOUS, AND MRS. NEWTON CROSLAND, Author of " llie Diamond Wedding, and other Poems," " Hubert Freeth's Prosperity ^^ ** Stories of the City of London^'' etc. HERNANI. THE KING'S DIVERSION. RUY BLAS. PROFUSELY ILLUSTRATED WITH ELEGANT WOOD ENGRAVINGS, -TTOTSTiJ^hajE: T7-. -1 NEW YORK: P. F. COLLIER, PUBLISHER. .M.... s/-. '-z;- CONTENTS. Hbrnani, translated by Mrs. Newton Crosland 21 The King's Diversion, translated by Fred'k L. Slous . 165 Buy Bias, translated by Mrs. Newton Crosland 267 411580 EDITOR'S PREFACE. S the Translator of "Hernani'' and "Ruy Bias," I may be permitted to offer a few remarks on the three great dramas which are now presented in an English form to the English-speaking public. Each of these works is preceded by the Author's Preface, which perhaps exhausts all that had to be said of the play which follows—from his own original point of view. It is curious to contrast the confident egotism, the frequent self-assertion, and the indignation at repression which mark the prefaces to '' Hernani " and ^' Le Roi s'Amuse " with the calm dignity of the very fine dramatic criticism which intro- duces the reader to "RuyBlas." But when the last-named tragedy was produced, Victor Hugo's fame was established and his literary position secure; he no longer had need to assert himself, for if a few enemies still remained, their voices were but as the buzzing of flies about a giant. -

The “Voix D'or”

in Silent Cinema New Findings and Perspectives edited by Monica Dall’Asta, Victoria Duckett, lucia Tralli RESEARCHING WOMEN IN SILENT CINEMA NEW FINDINGS AND PERSPECTIVES Edited by: Monica Dall’Asta Victoria Duckett Lucia Tralli Women and Screen Cultures Series editors: Monica Dall’Asta, Victoria Duckett ISSN 2283-6462 Women and Screen Cultures is a series of experimental digital books aimed to promote research and knowledge on the contribution of women to the cultural history of screen media. Published by the Department of the Arts at the University of Bologna, it is issued under the conditions of both open publishing and blind peer review. It will host collections, monographs, translations of open source archive materials, illustrated volumes, transcripts of conferences, and more. Proposals are welcomed for both disciplinary and multi-disciplinary contributions in the fields of film history and theory, television and media studies, visual studies, photography and new media. http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0/us/ # 1 Researching Women in Silent Cinema: New Findings and Perspectives Edited by: Monica Dall’Asta, Victoria Duckett, Lucia Tralli ISBN 9788898010103 2013. Published by the Department of Arts, University of Bologna in association with the Victorian College of the Arts, University of Melbourne and Women and Film History International Graphic design: Lucia Tralli 3 Researching Women in Silent Cinema: New Findings and Perspectives Peer Review Statement This publication has been edited through a blind peer review process. Papers from the Sixth Women and the Silent Screen Conference (University of Bologna, 2010), a biennial event sponsored by Women and Film History International, were read by the editors and then submitted to at least one anonymous reviewer. -

Notre Dame De Paris, by Victor Marie Hugo

Notre Dame de Paris Victor Marie Hugo The Harvard Classics Shelf of Fiction, Vol. XII. Selected by Charles William Eliot Copyright © 2001 Bartleby.com, Inc. Bibliographic Record Contents . Biographical Note Criticisms and Interpretations I. By Frank T. Marzials II. By Andrew Lang III. By G. L. Strachey List of Characters Author’s Preface to the Edition of 1831 Book I I. The Great Hall II. Pierre Gringoire III. The Cardinal IV. Master Jacques Coppenole V. Quasimodo VI. Esmeralda Book II I. From Scylla to Charybdis II. The Place de Grève III. Besos Para Golpes IV. The Mishaps Consequent on Following a Pretty Woman through the Streets at Night V. Sequel of the Mishap VI. The Broken Pitcher VII. A Wedding Night Book III I. Notre Dame II. A Bird’s-Eye View of Paris Book IV I. Charitable Souls II. Claude Frollo III. Immanis Pecoris Custos, Immanior Ipse IV. The Dog and His Master V. Further Particulars of Claude Frollo VI. Unpopularity Book V I. The Abbot of St.-Martin’s II. This Will Destroy That Book VI I. An Impartial Glance at the Ancient Magistracy II. The Rat-Hole III. The Story of a Wheaten Cake IV. A Tear for a Drop of Water V. End of the Wheaten Cake Book VII I. Showing the Danger of Confiding One’s Secret to a Goat II. Showing That a Priest and a Philosopher Are Not the Same III. The Bells IV. Fate V. The Two Men in Black VI. Of the Result of Launching a String of Seven Oaths in a Public Square VII.