How Do You Solve a Problem Like Cosette? Femininity and the Changing Face of Victor Hugo’S Alouette

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

La Fuerza Del Sino Romántico En Don Álvaro, Hernani Y Antony

LA FUERZA DEL SINO ROMÁNTICO EN DON ÁLVARO, HERNANI Y ANTONY M.a Mercedes Guirao Silvente Correo electrónico: [email protected] Resumen Muchos críticos románticos se esforzaron en alejar Don Álvaro o la fuerza del sino de los dos dramas franceses que le sirvieron de modelos indirectos: Hernani de Victor Hugo y Antony de Alexandre Dumas, por considerarlos corruptos e inmorales. Pero no hay que olvidar que la obra de Rivas fue gestada en Francia, durante el exilio del autor; en pleno contacto con la revolución liberal y romántica en Europa. Este artículo pretende, a través de un estudio comparativo entre estos tres dramas fundamentales del Romanticismo europeo, demostrar su estrecha relación. Las tres obras sorprenden por la fuerza de ese destino nefasto, causante de desgracia y muerte, que está directamente vinculado con la schicksalstragödie alemana y evidencian la superación de la vieja y rígida frontera entre Orden y Caos; entre lo Apolíneo y lo Dionisíaco. Palabras clave: drama romántico, Don Álvaro o la fuerza del sino, Hernani, Antony. THE FORCE OF THE ROMANTIC FATE IN DON ÁLVARO, HERNANI AND ANTONY Abstract 237 Many romantic critics strove to separate Don Álvaro or the force of the fate from the two French dramas which served as indirect models: Victor Hugo’s Hernani and Alexandre Dumas’ Antony, for considering them corrupt and immoral. But it should not be forgotten that Rivas’ play was conceived in France, during the exile of the author; in full contact with the liberal and romantic revolution in Europe. This article aims, through a comparative study of these three fundamental dramas of European romanticism, to demonstrate their close relationship. -

Les Mis Education Study Guide.Indd

And remember The truth that once was spoken, To love another person Is to see the face of God. THE CHARACTERS QUESTIONS / • In the end, what does Jean society who have lost their DISCUSSION IDEAS Valjean prove with his life? humanity and become brutes. Are there people in our society • Javert is a watchdog of the legal who fi t this description? • What is Hugo’s view of human process. He applies the letter nature? Is it naturally good, of the law to every lawbreaker, • Compare Marius as a romantic fl awed by original sin, or without exception. Should he hero with the romantic heroes of somewhere between the two? have applied other standards to a other books, plays or poems of man like Jean Valjean? the romantic period. • Describe how Hugo uses his characters to describe his view • Today, many believe, like Javert, • What would Eponine’s life have of human nature. How does that no mercy should be shown been like if she had not been each character represent another to criminals. Do you agree with killed at the barricade? facet of Hugo’s view? this? Why? • Although they are only on stage • Discuss Hugo’s undying belief • What does Javert say about his a brief time, both Fantine and that man can become perfect. past that is a clue to his nature? Gavroche have vital roles to How does Jean Valjean’s life play in Les Misérables and a illustrate this belief? • What fi nally destroys Javert? deep impact on the audience. Hugo says he is “an owl forced What makes them such powerful to gaze with an eagle.” What characters? What do they have does this mean? in common? Name some other • Discuss the Thénardiers as characters from literature that individuals living in a savage appear for a short time, but have a lasting impact. -

Jean Valjean, After Spending Nineteen Years in Jail and in the Galleys For

Les Miserables by Victor Hugo – A Summary (summary from http://education.yahoo.com/homework_help/cliffsnotes/les_miserables/4.html) Jean Valjean, after spending nineteen years in jail and in the galleys for stealing a loaf of bread to feed his starving family (and for several attempts to escape) is finally released, but his past keeps haunting him. At Digne, he is repeatedly refused shelter for the night. Only the saintly bishop, Monseigneur Myriel, welcomes him. Valjean repays his host's hospitality by stealing his silverware. When the police bring him back, the bishop protects his errant guest by pretending that the silverware is a gift. With a pious lie, he convinces them that the convict has promised to reform. After one more theft, Jean Valjean does indeed repent. Under the name of M. Madeleine he starts a factory and brings prosperity to the town of Montreuil. Alone and burdened with an illegitimate child, Fantine is on the way back to her hometown of Montreuil, to find a job. On the road, she entrusts her daughter to an innkeeper and his wife, the Thénardiers. In Montreuil, Fantine finds a job in Madeleine's (Valjean’s) factory and attains a modicum of prosperity. Unfortunately she is fired after it is discovered that she has an illegitimate child. At the same time, she must meet increasing financial demands by the Thénardiers. Defeated by her difficulties, Fantine turns to prostitution. Tormented by a local idler, she causes a disturbance and is arrested by Inspector Javert. Only Madeleine's (Valjean’s) forceful intervention keeps her out of jail. -

Les Mis, Lyrics

LES MISERABLES Herbert Kretzmer (DISC ONE) ACT ONE 1. PROLOGUE (WORK SONG) CHAIN GANG Look down, look down Don't look 'em in the eye Look down, look down You're here until you die. The sun is strong It's hot as hell below Look down, look down There's twenty years to go. I've done no wrong Sweet Jesus, hear my prayer Look down, look down Sweet Jesus doesn't care I know she'll wait I know that she'll be true Look down, look down They've all forgotten you When I get free You won't see me 'Ere for dust Look down, look down Don't look 'em in the eye. !! Les Miserables!!Page 2 How long, 0 Lord, Before you let me die? Look down, look down You'll always be a slave Look down, look down, You're standing in your grave. JAVERT Now bring me prisoner 24601 Your time is up And your parole's begun You know what that means, VALJEAN Yes, it means I'm free. JAVERT No! It means You get Your yellow ticket-of-leave You are a thief. VALJEAN I stole a loaf of bread. JAVERT You robbed a house. VALJEAN I broke a window pane. My sister's child was close to death And we were starving. !! Les Miserables!!Page 3 JAVERT You will starve again Unless you learn the meaning of the law. VALJEAN I know the meaning of those 19 years A slave of the law. JAVERT Five years for what you did The rest because you tried to run Yes, 24601. -

Les Miserables Audition Pack Stanwell Senior Musical Rehearsals

Les Miserables Audition Pack Stanwell Senior Musical Rehearsals: September – December 2019 Show dates: Monday 16th –Thursday 20th December 2019 Contents Audition Dates Important information Character information Audition Material Recall Material We are really looking forward to the auditions, good luck! The Auditions In the audition, you will sing in groups. If you would like to be a member of chorus, you will not be asked to sing alone Week Day/Date Time Who? Where? 2 Mon 9th Sept 3-5pm BOYS Auditorium 2 Wed 11th 3-5pm GIRLS Auditorium Sept 2 Thurs 12th 3-5pm Little COSETTE & GAVROCHE Auditorium Sept AUDITIONS (Open to year 8/9 pupils who attend junior choir) 3 Mon 16th 3-5.30 RECALL 1 Auditorium Sept 3 Wed 18th 3-5.30 RECALL 2 Auditorium Sept 3 Thurs 19th 3-4 DANCE AUDITIONS Auditorium Sept Dancers must do a group singing audition Audition Material (more info later in this pack) BOYS You may pick any of the below songs to sing in your audition. Chorus member (Drink with me) Enjorlas (Red and Black) Jean Val Jean (Soliloquy) Javert (Stars) Marius (Empty Chairs) Thenardier (Master of the House) Gavroche (Little People) Bishop (Prologue) GIRLS Chorus member/Eponine (On My Own) Mrs Thenardier (Master of the House ) Fantine (I dreamed a dream) Cosette (In my life) Little Cosette (Castle on a Cloud) Please note that Senior Choir rehearsals will take place on a Friday, we do expect pupils in the school musicals to take part in the school choirs. Important Information Rehearsals are as follows: Monday – small groups & principals Wednesday – whole cast Thursday – solos/duets You must be available for the important rehearsals & shows below. -

Lesmis-Program-Apr30

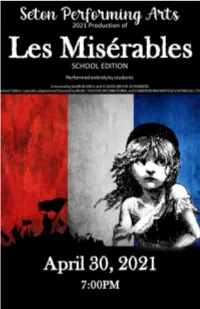

Seton Performing Arts Production of Les Misérables School Edition Performed entirely by students A musical by ALAIN BOUBLIL and CLAUDE-MICHEL SCHÖNBERG Based on the novel by VICTOR HUGO Music by CLAUDE-MICHEL SCHÖNBERG Lyrics by HERBERT KRETZMER Original French text by ALAIN BOUBLIL and JEAN-MARC NATEL Additional materials by JAMES FENTON Adapted by TREVOR NUNN and JOHN CAIRD Original Orchestrations by JOHN CAMERON New Orchestrations by CHRISTOPHER JAHNKE, STEPHEN METCALFE and STEPHEN BROOKER Originally Produced by CAMERON MACKINTOSH School Edition specially adapted and licensed by MUSIC THEATRE INTERNATIONAL and CAMERON MACKINTOSH (OVERSEAS) LTD LES MISERABLES SCHOOL EDITION is presented by arrangement with Music Theatre International (MTI). All authorized performance materials are also supplied by MTI. www.mtishows.com Please be advised, in Act II the show contains loud bangs and flashing red lights. Any video and/or audio recording of this production is strictly prohibited. The Cast (In Order of Appearance) Jean Valjean ........................................................................... Adam Ackerman Javert .............................................................................................. Atticus Fauci Bishop of Digne ................................................................. Mr. Rich Vollmer Factory Foreman ...................................................................... Fisher Sullivan Fantine ................................................................................. Samara DeSouza Bamatabois -

Dark Knight's War on Terrorism

The Dark Knight's War on Terrorism John Ip* I. INTRODUCTION Terrorism and counterterrorism have long been staple subjects of Hollywood films. This trend has only become more pronounced since the attacks of September 11, 2001, and the resulting increase in public concern and interest about these subjects.! In a short period of time, Hollywood action films and thrillers have come to reflect the cultural zeitgeist of the war on terrorism. 2 This essay discusses one of those films, Christopher Nolan's The Dark Knight,3 as an allegorical story about post-9/11 counterterrorism. Being an allegory, the film is considerably subtler than legendary comic book creator Frank Miller's proposed story about Batman defending Gotham City from terrorist attacks by al Qaeda.4 Nevertheless, the parallels between the film's depiction of counterterrorism and the war on terrorism are unmistakable. While a blockbuster film is not the most obvious starting point for a discussion about the war on terrorism, it is nonetheless instructive to see what The Dark Knight, a piece of popular culture, has to say about law and justice in the context of post-9/11 terrorism and counterterrorism.5 Indeed, as scholars of law and popular culture such as Lawrence Friedman have argued, popular culture has something to tell us about society's norms: "In society, there are general ideas about right and wrong, about good and bad; these are templates out of which legal norms are cut, and they are also ingredients from which song- and script-writers craft their themes and plots."6 Faculty of Law, University of Auckland. -

The Evolution of Batman and His Audiences

Georgia State University ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University English Theses Department of English 12-2009 Static, Yet Fluctuating: The Evolution of Batman and His Audiences Perry Dupre Dantzler Georgia State University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/english_theses Part of the English Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation Dantzler, Perry Dupre, "Static, Yet Fluctuating: The Evolution of Batman and His Audiences." Thesis, Georgia State University, 2009. https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/english_theses/73 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Department of English at ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. It has been accepted for inclusion in English Theses by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. STATIC, YET FLUCTUATING: THE EVOLUTION OF BATMAN AND HIS AUDIENCES by PERRY DUPRE DANTZLER Under the Direction of H. Calvin Thomas ABSTRACT The Batman media franchise (comics, movies, novels, television, and cartoons) is unique because no other form of written or visual texts has as many artists, audiences, and forms of expression. Understanding the various artists and audiences and what Batman means to them is to understand changing trends and thinking in American culture. The character of Batman has developed into a symbol with relevant characteristics that develop and evolve with each new story and new author. The Batman canon has become so large and contains so many different audiences that it has become a franchise that can morph to fit any group of viewers/readers. Our understanding of Batman and the many readings of him gives us insight into ourselves as a culture in our particular place in history. -

The Worlds of Rigoletto: Verdiâ•Žs Development of the Title Role in Rigoletto

Florida State University Libraries Electronic Theses, Treatises and Dissertations The Graduate School 2008 The Worlds of Rigoletto Verdi's Development of the Title Role in Rigoletto Mark D. Walters Follow this and additional works at the FSU Digital Library. For more information, please contact [email protected] THE FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF MUSIC THE WORLDS OF RIGOLETTO VERDI’S DEVELOPMENT OF THE TITLE ROLE IN RIGOLETTO By MARK D. WALTERS A Treatise submitted to the College of Music in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Music Degree Awarded: Spring Semester, 2008 The members of the Committee approve the Treatise of Mark D. Walters defended on September 25, 2007. Douglas Fisher Professor Directing Treatise Svetla Slaveva-Griffin Outside Committee Member Stanford Olsen Committee Member The Office of Graduate Studies has verified and approved the above named committee members. ii I would like to dedicate this treatise to my parents, Dennis and Ruth Ann Walters, who have continually supported me throughout my academic and performing careers. iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to express my gratitude to Professor Douglas Fisher, who guided me through the development of this treatise. As I was working on this project, I found that I needed to raise my levels of score analysis and analytical thinking. Without Professor Fisher’s patience and guidance this would have been very difficult. I would like to convey my appreciation to Professor Stanford Olsen, whose intuitive understanding of musical style at the highest levels and ability to communicate that understanding has been a major factor in elevating my own abilities as a teacher and as a performer. -

Pierre LAFORGUE : "Bug Jargal, Ou De La Difficulté D'écrire En Style Blanc"

Retour Pierre Laforgue : Bug Jargal ou de la difficulté d'écrire en "style blanc" Communication au Groupe Hugo du 17 juin 1989. Ce texte peut être téléchargé au format pdf Mais, qu'est-ce que c'est donc un Noir ? Et d'abord, c'est de quelle couleur ? Jean Genet Il s'agit ici de montrer comment se fait l'inscription de l'idéologie dans le texte, comment dans les contradictions et les confusions du texte s'opère, ou ne s'opère pas, un processus de conceptualisation, d'appropriation et de transformation du réel historique et politique, comment enfin c'est l'écriture elle-même qui produit sa propre idéologie, et non le contraire. Autrement dit, je pose qu'il est impossible d'entreprendre la lecture, de l'idéologie d'un texte sans prendre en compte d'abord les modalités de sa production, en l'occurrence sa scripturalité. De là un refus clair et avoué, celui de porter a priori un jugement idéologique auquel on soumettrait la lisibilité du texte, un tel jugement n'étant pas pertinent puisqu'il méconnaîtrait le travail de l'écriture qui, lui, pour le coup, est fondamentalement idéologique. Un tel travail, Bug-Jargal1 dans ses deux versions de 1820 et de 1825-1826 permet d'en voir les implications, tant les différences d'ordre idéologique entre la nouvelle et le roman sont importantes. L'intrigue n'a pas changé, Bug- Jargal meurt toujours à la fin, et de manière générale les ajouts se présentent comme des intercalations qui ne viennent pas modifier la trame d'ensemble. -

Les Misérables School Edition Parts Chart MUSIC THEATRE INTERNATIONAL

Les Misérables School Edition Parts Chart MUSIC THEATRE INTERNATIONAL SCENE Characters ACT I 1 Prologue Convict 1 Convict 2 Convict 3 Convict 4 Convict 5 Javert Valjean Farmer Laborer Bishop Constable 1 Constable 2 The Chain Gang Constables Laborers Sister, Servant Onlookers 2 End of the Day Foreman Worker 1 Worker 2 Woman Girl 1 Girl 2 Girl 3 Girl 4 Girl 5 Fantine Valjean Chorus - the poor Chorus - the workers Women 3 I Dreamed a Dream Fantine 4 The Docks Sailor 1 Sailor 2 Sailor 3 Old Woman (hair) Pimp Whore 1 Whore 2 Whore 3 Prostitutes Bamatbois Javert Constables (nonsing) 2 Bystanders (nonsing) Valjean 5 The Cart Crash Valjean Cart scene to courtroom Onlooker 1 Onlooker 2 Onlooker 3 Onlooker 4 Fauchelevant Javert Bystanders (nonsing) 6 Fantine's Death Fantine Valjean Javert Nuns (nonsing) Les Misérables School Edition Parts Chart MUSIC THEATRE INTERNATIONAL SCENE Characters 7 Little Cosette Young Cosette Madame Thenardier Young Eponine (nonsing) 8 The Innkeeper's Song Thenardier Madame Thenardier Customers 9 The Bargain Valjean Thenardier Madame Thenardier Young Cosette (nons) 10 The Beggars Gavroche Marius Enjolras Solo Urchin Beggars Students Thenardier family 11 The Robbery Madame Thenardier Marius Eponine Thenardier Valjean Javert Thenardier family Beggars Cosette Valjean Constables 12 Stars Javert Gavroche Eponine Marius 13 The ABC Café Combferre Feuilly Courfeyrac Enjolras Joly Grantaire Gavroche Students 14 The People's Song Enjolras Combferre Feuilly Students Chorus 15 Rue Plumet Cosette Valjean Marius Eponine 16 A Heart Full -

Agape Love and Les Mis

Agape Love and Les Mis Prepared by Veronica Burchard Lesson Overview Lesson Details In this unit, students learn about agape or Subject area(s): English, Film, Religion, Living sacrificial love by viewing, discussing, and as a Disciple of Jesus Christ in Society, writing about the film (or play) Les Miserables, Responding to the Call of Jesus Christ , Social based on the novel by Victor Hugo. I used the Justice Tom Hooper film starring Hugh Jackman and Anne Hathaway. Grade Level: High School Since the film is long and can be hard to follow, Resource Type: Close Reading/Reflection, we watched it in short bursts, pausing to clarify Discussion Guide, Video characters and situations however needed. After each viewing session we spent several Special Learners days talking about the plot, characters, settings, This resource was developed with the following and so forth. My main goal was to make sure special learners in mind: they understood what was happening in each scene, and how each scene related to the Traditional Classroom whole. We would also listen to the songs Homeschooled Students together. This lesson desribes the process we followed and includes a unit assessment with a character quote matching exercise, reflection questions, and two essay questions. The author of this lesson shared it with other educators within the Sophia Institute for Teachers Catholic Curriculum Exchange. Find more resources and share your own at https://www.SophiaInstituteforTeachers.org. Lesson Plan In this unit, students learn about agape or sacrificial love by viewing, discussing, and writing about the film (or play) Les Miserables, based on the novel by Victor Hugo.