Lachende Angst

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

John Dewey, Maria Montessori, and Objectivist Educational Philosophy During the Postwar Years

73 Historical Studies in Education / Revue d’histoire de l’éducation ARTICLES / ARTICLES “The Ayn Rand School for Tots”: John Dewey, Maria Montessori, and Objectivist Educational Philosophy during the Postwar Years Jason Reid ABSTRACT Objectivism, the libertarian philosophy established by Ayn Rand during the postwar years, has attracted a great deal of attention from philosophers, political scientists, economists, and English professors alike in recent years, but has not received much notice from historians with an interest in education. This article will address that problem by discussing how Rand and her followers established a philosophy of education during the 1960s and 1970s that was based, in part, on vilifying the so-called collectivist ideas of John Dewey and lionizing the so-called individualist ideas of Maria Montessori. Unfortunately, the narrative that emerged during this time seriously misrepresented the ideas of both Dewey and Montessori, resulting in a some- what distorted view of both educators. RÉSUMÉ L’objectivisme, philosophie libertaire conçue par Ayn Rand dans la période de l’après-guerre, a suscitée beaucoup d’attention de la part des philosophes, politologues, économistes et profes- seurs de littérature anglaise, mais rien de tel chez les historiens de l’éducation. Cet article cor- rige cette lacune, en montrant comment durant les années 1960 et 1970 Rand et ses partisans ont établi une philosophie de l’éducation qui s’appuyait, en partie, sur la diffamation des idées prétendues collectivistes de John Dewey et l’idolâtrie de l’individualisme de Maria Montessori. Malheureusement, leurs travaux ont donné une fausse image des idées de Dewey et Montessori et conséquemment ont déformé les théories ces deux éducateurs. -

Comprachicos John Boynton Kaiser

Journal of Criminal Law and Criminology Volume 4 | Issue 2 Article 8 1913 Comprachicos John Boynton Kaiser Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarlycommons.law.northwestern.edu/jclc Part of the Criminal Law Commons, Criminology Commons, and the Criminology and Criminal Justice Commons Recommended Citation John Boynton Kaiser, Comprachicos, 4 J. Am. Inst. Crim. L. & Criminology 247 (May 1913 to March 1914) This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Northwestern University School of Law Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Criminal Law and Criminology by an authorized editor of Northwestern University School of Law Scholarly Commons. THE COMPRACHICOS. JVOE BOYNTON KAISER.' The fertile brain of Victor Hugo-novelist, dramatist, poet, states- man, and sociologist-has given the world numerous studies in criminal sociology which, for human interest, will ever remain classic. Less classic and less well known than many of these studies, yet strangely combining fact and fiction is the second of the two preliminary chapters to L'Homma. Qui Bit wherein Hugo describes at length a people whom he calls by the Spanish compound word Comprachicos, signifying child-buyers. It is a chronicle of crimes and punishments in which strange history is written and cruel and forgotten laws recall to mind ages long since past. Much condensed, though freely employing his own language, Hugo's description of the Comprachicos is given here; the language of no other will suffice. The Comprachicos, or Comprapequefios, were a hideous and nondescript association of wanderers, famous in the 17th century, forgotten in the 18th, unheard of in the 19th. -

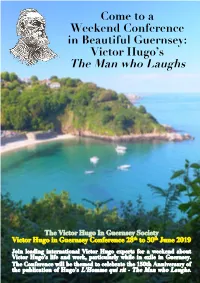

Victor Hugo's the Man Who Laughs

Come to a Weekend Conference in Beautiful Guernsey: Victor Hugo’s The Man who Laughs The Victor Hugo In Guernsey Society Victor Hugo in Guernsey Conference 28th to 30th June 2019 Join leading international Victor Hugo experts for a weekend about Victor Hugo’s life and work, particularly while in exile in Guernsey. The Conference will be themed to celebrate the 150th Anniversary of the publication of Hugo’s L’Homme qui rit - The Man who Laughs. th Victor Hugo Saturday 29 June In Guernsey 9:00 CONFERENCE registration in the Harry Bound Room at Les Côtils Centre. 2019 9:30 BEAUTIFUL INSIDE & OUT, by GÉRARD AUDINET ‘Beautiful inside and out.’ Does the soul have a face? We are all familiar A with the concept of ‘inner beauty,’ but how do artists approach the problem of Conference with L’Homme Qui Rit depicting it? This illustrated talk will reflect on the representations of ugliness Supported by the Guernsey 28th to 30th June and beauty in later arts and media of Victor Hugo’s ‘The Man who Laughs.’ Arts The Victor Hugo In Guernsey Society Commission 10:30 Break for discussion, Coffee or tea. The Victor Hugo In Guernsey Society 11:00 JUSTICE IN THE MAN WHO LAUGHS, by MYRIAM ROMAN Victor Hugo in Guernsey 2019 Conference The representation of justice in ‘The Man who Laughs’ passes through a series of 28th to 30th June 2019 images and myths. The singularity of this novel seems to be to ask the last question of a possible divine injustice through a series of metaphors that project, on the PROGRAMME cosmos, terrifying images of the process and the punishment. -

George Eliot 2019 Paper Abstracts

Francois d'Albert-Durade, ‘Mary Ann Evans’ (1880-81), courtesy of the Herbert Art Gallery and Museum, Coventry GEORGE ELIOT 2019: AN INTERNATIONAL BICENTENARY CONFERENCE 17-19 July 2019, College Court, University of Leicester ABSTRACTS @ge2019conf #ge2019conf PANEL ABSTRACTS WEDNESDAY 17 JULY PANEL A (14.30-16.00) A1: George Eliot’s Philosophical Practices (Oak 1) Panel Abstract: This panel will consider the practices through which Eliot engaged with philosophy over the course of her career. It will investigate the ways in which Eliot explored philosophical texts and ideas. It will also investigate how she approached philosophical problems, as a philosophical thinker in her own right. Our focus will be on her habits, methods, and modes of inquiry. We will ask how Eliot’s particular approaches to thinking, reading, translating, notetaking, reviewing, fiction writing, and verse writing shaped how she understood and undertook philosophy. We will explore the significance of her experiments with form, style, and genre for her philosophical thinking. And we will consider how she drew upon all these practices of engagement to enable her readers to think philosophically too. Our three papers will address different aspects of Eliot’s philosophical practices, focusing on her dialectical thinking, her translating, and her notetaking respectively, but they also will be complementary, and we will begin the panel with a brief introduction, in which we will suggest why thinking about practice is key to thinking about Eliot’s engagement with philosophy more broadly. Isobel Armstrong (Birkbeck), ‘George Eliot: Hegel Internalised’ It is clear, when we see the early and quite clumsy attempts of G H Lewes to assimilate Hegelian thinking in the 1840s, that Hegel represented to him a new form of knowledge, comparable to the way people grappled with the new knowledges of the twentieth century, Freud and Marx. -

French Romanticism and Victor Hugo Fabio Calzolari1

MFU CONNEXION, 4(2) || page 140 A Laugh that Hides Sadness: French Romanticism and Victor Hugo Fabio Calzolari1 “O come and love Thou art the soul, I am the heart.” (2004: 409) Romanticism (also known as Romantic era) was a cultural movement originated in Europe (starting in the 17th century with the German “Sturm und 2 3 Drang ”) that exalted (mostly polarized) feelings as loci of aesthetic (αίσθησιs) experience. In France, this multifocal movement (embodied in literature, visual, science and social studies) promoted spirituality over rationality, unpredictability 4 against order, distancing itself from the previous “Siècle des Lumières ”. The 1 English instructor at Chiang Rai Rajabhat University, Chiang Rai, Thailand, E-mail: [email protected] 2 It was a German philosophical and artistic phenomenon. See “Sturm und Drang” by Alan Leidner (1992), published by Bloomsbury Academic 3 Aesthetic (Αισθητική) was a part of Greek philosophy that studies the notion of beauty. In 1750, Alexander Gottlieb Baumgarten gave the word a new usage (modern one), enlarging the studies of beauty itself to an analysis that engulfed a notion of human knowledge based on sensation. Beauty was relegated to a minor part of a spectrum that structures perceived reality on an emotional base. 4 The Age of enlighten was a European philosophical movement that prioritized logic and rationality over sensations. MFU CONNEXION, 4(2) || page 141 Romantic era framed a literary turnover where boundaries are blurred by juxtapositions of styles and narrative structures. During this era, societies started promoting autonomous national thrusts and reciprocal cultural independence; this momentum was noteworthy expressed by J.G. -

Disability Ecology: Re-Materializing U.S

Disability Ecology: Re-Materializing U.S. Fiction from 1890-1940 By Joshua Kupetz A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (English Language and Literature) in the University of Michigan 2016 Doctoral Committee: Professor June Howard, Co-Chair Professor David T. Mitchell, Co-Chair, George Washington University Professor Tobin A. Siebers (Chair, Deceased) Professor Paul N. Edwards Emeritus Professor Alan Wald Professor Patricia Yaeger (Deceased) If cows and horses or lions had hands and could draw, then horses would draw the forms of gods like horses, cows like cows, making their bodies similar in shape to their own. Xenophanes © Jonathan Joshua Kupetz 2016 Dedication For Shana, Edith, and Oscar ii Acknowledgements I first learned of disability studies from K. Wendy Moffat, my mentor and colleague in the Department of English at Dickinson College, who brought to my attention the conference “Disability Studies and the University” hosted by Emory University in 2004. At that conference, I was introduced to a discipline that has changed my life’s path. I was also introduced to Tobin Siebers, my late mentor and dissertation chair. If not for Wendy’s encouragement, I would not have met Tobin; if not for meeting Tobin, I would not have applied to Michigan; if not for Michigan, I would have missed the great pleasure of working with passionate and engaged professors like Lucy Hartley, John Whittier-Ferguson, Gabrielle Hecht, and Robert Adams, as well as the brilliant colleague-comrades Jina Kim, Jenny Kohn, and Liz Rodrigues. And if not for stockpiling years of Tobin’s stern encouragement—typically prompted by Jill Greenblatt Siebers, his wife—I may not have finished this project after losing both Patsy Yaeger and him. -

The Narcissist on Instagram: Epigrams and Observations the First Book by Sam Vaknin, Ph.D

The Narcissist on Instagram: Epigrams and Observations The First Book by Sam Vaknin, Ph.D. Professor of Psychology Southern Federal University, Rostov-on-Don, Russian Federation and SIAS-CIAPS Centre for International Advanced Professional Studies (SIAS Outreach) The author is NOT a Mental Health Practitioner The book is based on interviews since 1996 with 2000 people diagnosed with Narcissistic and Antisocial Personality Disorders (narcissists and psychopaths) and with thousands of family members, friends, therapists, and colleagues. Editing and Design: Lidija Rangelovska A Narcissus Publications Imprint Prague & Haifa 2021 © 2017-21 Copyright Narcissus Publications All rights reserved. This book, or any part thereof, may not be used or reproduced in any manner without written permission from: Sam Vaknin – write to: [email protected] To get FREE updates of this book JOIN the Narcissism Study List. To JOIN, visit our Web sites: http://www.narcissistic-abuse.com/narclist.html or http://groups.yahoo.com/group/narcissisticabuse Visit the Author's Web site http://www.narcissistic-abuse.com Facebook http://www.facebook.com/samvaknin http://www.facebook.com/narcissismwithvaknin YouTube channel http://www.youtube.com/samvaknin Instagram https://www.instagram.com/vakninsamnarcissist/ (archive) https://www.instagram.com/narcissismwithvaknin/ Buy other books and video lectures about pathological narcissism and relationships with abusive narcissists and psychopaths here: http://www.narcissistic-abuse.com/thebook.html Buy Kindle books here: http://www.amazon.com/s/ref=ntt_athr_dp_sr_1?_encoding=UTF8&field-author=Sam%20Vaknin&search-alias=digital- text&sort=relevancerank C O N T E N T S Throughout this book click on blue-lettered text to navigate to different chapters or to access online resources I. -

Blindness As Metaphor Naomi Schor

Blindness as Metaphor Naomi Schor differences: A Journal of Feminist Cultural Studies, Volume 11, Number 2, Summer 1999, pp. 76-105 (Article) Published by Duke University Press For additional information about this article https://muse.jhu.edu/article/9603 Access provided by University of Athens (or National and Kapodistrian Univ. of Athens) (14 Sep 2017 18:59 GMT) NAOMI SCHOR Blindness as Metaphor There is a casual cruelty, an offhanded thoughtlessness, about metaphors of illness. As Susan Sontag demonstrated some years ago, illness constitutes a special category of metaphor; to speak of cancer as just another word for what the dictionary defines as “a source of evil and anguish” is to massively deny the reality of mutilating surgery, chemotherapy, hair loss, pain, and hospice care, but also, and more importantly, to freight an already onerous diagnosis with the crippling stigma of an unspeakable disease.1 Sontag’s main concern in writing her influential essay was in fact double: on the one hand, to dispel what she calls variously “metaphorical thinking” (3) and “the trappings of meta- phor” (5) that surround cancer; on the other, to debunk what she describes as myth, or what we might call by analogy, “mythical thinking.” Just how metaphor and myth mutually inform each other is never spelled out in Illness as Metaphor; they are used interchangeably—although metaphor is granted a special status in light of its rhetorical antecedents. The impetus that drives Sontag’s essay is not so much, as she makes explicit in her more recent sequel and companion essay, “AIDS and its Metaphors,” the idealistic desire to contribute to cultural transformation, as the more d – i – f – f – e – r – e – n – c – e – s : A Journal of Feminist Cultural Studies 11.2 (1999) differences 77 urgent therapeutic goal of changing the prospects of those who are diagnosed with those fearsome diseases of our modern and postmodern time, cancer and AIDS; for the misuse of metaphor and the proliferation of myth can, in Sontag’s view, prove fatal. -

Montessori: Now More Than Ever Dr Annette M

Montessori: Now More Than Ever Dr Annette M. Haines is the Director of Training for the Montessori Training By Dr Annette Haines Center of St. Louis. Dr Haines is an internationally recognised lecturer, examiner, and trainer for AMI. She has been involved in the field of Montessori education since 1972 and has extensive background in the Children’s House classroom. Dr Haines holds both AMI Primary and Elementary Diplomas. Additionally, she has a Bachelor of Arts degree in English literature, a masters degree in education, and a doctorate in education with research focused on concentration and normalisation within the Montessori prepared environment. She currently chairs the AMI 2007 Scientific Pedagogy Committee and is a member of the Issue 1 Executive Committee of the AMI Board. Like everything in the universe, the human child is created in when they cannot have the special activity that nature imposes on accordance with the ordered power of nature. The template is ‘a the human personality in order to grow well. According to Maria very delicate and great thing which must be cared for. It is like a Montessori, all the disordered psychic movements of children come psychic embryo.’1 All the organs of the body develop in the embryo from two sources in the beginning: mental starvation and lack of in the womb so delicately, yet so prearranged, that scientists can activity. now describe physical changes in the foetus day by day. Nature defends this physical development by providing a special protective Now it seems unthinkable that today, in this modern information growing place. -

Der JOKER – Personifiziertes Chaos Und Medienübergreifender Superschurke“

DIPLOMARBEIT Titel der Diplomarbeit „Der JOKER – personifiziertes Chaos und medienübergreifender Superschurke“ Die intermediale Figurenentwicklung des Comicschurken Joker vom gezeichneten zum bewegten Bild. Verfasserin Doris Rainalter angestrebter akademischer Grad Magistra der Philosophie (Mag.phil.) Wien, 2013 Studienkennzahl lt. Studienblatt: A 317 Studienrichtung lt. Studienblatt: Theater,- Film- und Medienwissenschaft Betreuer: Doz. Dr. Clemens K. Stepina Danksagung Ich möchte mich bei meiner gesamten Familie, insbesondere aber bei meinen Eltern Ingrid und Guido Rainalter für die langjährige Unterstützung während meines Studiums bedanken. Ohne Eure Liebe, Geduld, Hilfe und die aufmunternden Worte, die mich in Zeiten der Unsicherheit wieder aufgebaut haben, wären viele Hürden ungemeistert geblieben. Besonderer Dank gilt auch meinem Betreuer Dr. Clemens Stepina, der mich durch seine Vorschläge und Ideen bei der Themenausarbeitung von Anfang an unterstützt und mir die Zeit gegeben hat, die diese Arbeit bis zu ihrer Vollendung brauchte. Einen Dank auch an einige besonders wichtige Freundinnen, die mir immer mit Rat und Tat zur Seite gestanden sind und mich aufgebaut haben, ging es mit der Arbeit auch noch so langsam voran: Simone, Jenny, Karin, Claudia, Maria, Michi, Angelika, Monika, Kora, Melanie, Martina, Eva, Julia, Eveliene, Adrienn und Iris. Ich danke euch. i Inhaltsverzeichnis EINLEITUNG ................................................................................................................................................. -

The Comprachicos

Ayn Rand The Comprachicos I The comprachicos, or comprapequeños, were a strange and hideous nomadic association, famous in the seventeenth century, forgotten in the eighteenth, unknown today … Comprachicos, as well as comprapequeños, is a compound Spanish word that means “child-buyers.” The comprachicos traded in children. They bought them and sold them. They did not steal them. The kidnapping of children is a different industry. And what did they make of these children? Monsters. Why monsters? To laugh. The people need laughter; so do the kings. Cities require side-show freaks or clowns; palaces require jesters … To succeed in producing a freak, one must get hold of him early. A dwarf must be started when he is small … Hence, an art. There were educators. They took a man and turned him into a miscarriage; they took a face and made a muzzle. They stunted growth; they mangled features. This artificial production of teratological cases had its own rules. It was a whole science. Imagine an inverted orthopedics. Where God had put a straight glance, this art put a squint. Where God had put harmony, they put deformity. Where God had put perfection, they brought back a botched attempt. And, in the eyes of connoisseurs, it is the botched that was perfect … The practice of degrading man leads one to the practice of deforming him. Deformity completes the task of political suppression … The comprachicos had a talent, to disfigure, that made them valuable in politics. To disfigure is better than to kill. There was the iron mask, but that is an awkward means. -

16Moretti V2 Ch16 274-294.Qxd

COPYRIGHT NOTICE: Edited by Franco Moretti: The Novel, Volume 2: Forms and Themes is published by Princeton University Press and copyrighted, © 2006, by Princeton University Press. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form by any electronic or mechanical means (including photocopying, recording, or information storage and retrieval) without permission in writing from the publisher, except for reading and browsing via the World Wide Web. Users are not permitted to mount this file on any network servers. Follow links Class Use and other Permissions. For more information, send email to: [email protected] UMBERTO ECO Excess and History in Hugo’s Ninety-three In 1902, a small review, L’Hermitage, asked two hundred French writers who their favorite poet was. André Gide replied, “Hugo, hélas!” Gide would have to go to great lengths in the years to come to explain his state ment.1 In the present essay I am not particularly interested in this episode, since Gide was speaking of Hugo the poet, but his cry (of pain? disappoint ment? begrudging admiration?) weighs heavily on the shoulders of anyone who has ever been invited to judge Hugo the novelist—or even the author of a single novel. Such is the case with this revisitation of Ninety-three. Alas (hélas!), however many shortcomings in the novel one can list and analyze, starting with its oratorical incontinence, the same defects appear splendid when we begin to delve into the wound with our scalpel. Like a worshiper of Bach and his disembodied, almost mental architecture, who discovers that Beethoven has achieved mightier tones than many more tem perate harpsichords ever could—why fight the urge to surrender? Who could be immune to the power of the Fifth or Ninth Symphony? Was Hugo the greatest French novelist of his century? With good reason you might prefer Stendhal, Balzac, or Flaubert.