The Comprachicos

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Conference Programme Guernsey 28-30 June 2019 Organised by the Victor Hugo in Guernsey Society

IN GUERNSEY CONFERENCE 2019 Conference Programme Guernsey 28-30 June 2019 Organised by The Victor Hugo in Guernsey Society Supported by the Guernsey Arts André Gill illustration for L’Eclipse, 25 April 1869, from the Gérard Pouchain collection. from the Gérard Pouchain April 1869, 25 L’Eclipse, André Gill illustration for Commission About The Victor Hugo In Guernsey Society Welcome from The Victor Hugo In Guernsey Society Victor Hugo wrote many of his greatest works on The Victor Hugo in Guernsey Society welcomes you to its 3rd In~ a letter to his publisher, Lacroix, in December the island of Guernsey, a small British dependency Victor Hugo in Guernsey conference. This weekend in the 1868, after he had announced the publication of 20 miles off the coast of France. Hugo was in exile, but island of Hugo’s exile will focus on the novel Hugo published a new work by Hugo which he characterised as a Roman despite his grief for his family and his homeland he was 150 years ago in 1869, L’Homme qui rit, (The Man who Laughs), historique, the famous novelist wrote: inspired by the beauty of the rocky landscape and seas written on Guernsey and set in England. Our sister island of “When I paint history I make my historical characters that surrounded him to produce magnificent novels – Alderney plays a pivotal part in the narrative, and even our old do only what they have done or could do, their characters including Les Misérables, and Les Travailleurs de la mer – Norman law finds its way into the text. -

Lundi 1 Avril 2019 : *Victor Hugo Est Un Des Personnages Illustres Qui

Lundi 1er avril 2019 : *Victor Hugo est un des personnages illustres qui ont fait l’objet de pochoirs disséminés dans le 5e arrondissement de Paris et réalisés par Christian Guémy alias C215, artiste urbain. Leur localisation est indiquée sur un plan disponible à l’entrée du Panthéon ou à la Mairie du 5e. Ces portraits sont exposés depuis le 10 juillet et jusqu’à juin 2019. Celui de Hugo se trouve, Carine Fréard l’a repéré, en venant du boulevard St-Michel, rue Soufflot, 100 m environ après avoir croisé la rue Saint-Jacques, sur le trottoir de gauche. *10h à 12h 30 et 14h à 17h 30 : L’Invisible au Visible mêlé, exposition inédite de dessins de Hugo à la Maison Vacquerie-Musée Victor Hugo, Rives-en-Seine (Villequier), Du 9 mars au 26 mai, tous les jours sauf le mardi et le dimanche matin ; 14h à 17h 30 le dimanche. *10h 30 à 17h 30 : Exposition « La Poésie sans mots » (du 15 mars au 15 avril) à la Bibliothèque du 1er étage et Exposition permanente, Maison natale de Victor Hugo, 140 Grande Rue, sauf le mardi : Rez-de chaussée - « Hugo bisontin ? » (hommages des Bisontins à l’auteur et liens tissés par lui avec sa ville natale) -; 1er étage - « L’homme engagé » (exposition permanente) ; quatre thématiques et leurs prolongements aujourd’hui : la liberté d’expression (partenaire : Reporters sans frontières); misère- égalité-justice (partenaire : ATD Quart Monde pour la lutte contre la misère) ; l’enfance et l’éducation, dans la chambre natale (partenaire : Unicef pour les droits de l’enfant) ; liberté des peuples, dans le salon de la rue de Clichy, où Hugo a reçu quantité d’invités de 1874 à 1878, donné par Alice et Edouard Lockroy à la ville de Besançon (partenaire : Amnesty International) ; cave voûtée - salle Gavroche, espace pour l’action culturelle – projections, conférences, expositions temporaires, lectures, petites mises en scène théâtrales ou musicales – capable d’accueillir 65 personnes . -

THE MAN WHO LAUGHS / 1927 (O Homem Que Ri)

CINEMATECA PORTUGUESA-MUSEU DO CINEMA REVISITAR OS GRANDES GÉNEROS - A COMÉDIA (PARTE III): O RISO 2 de dezembro de 2020 THE MAN WHO LAUGHS / 1927 (O Homem Que Ri) um filme de Paul Leni Realização: Paul Leni / Argumento: J. Grubb Alexander, segundo o romance “L’ Homme Qui Rit” de Victor Hugo, adaptado por Bela Sekely / Fotografia: Gilbert Warrenton / Direcção Artística: Charles D. Hall, Joseph Wright, Thomas F. O’Neill / Figurinos: David Cox, Vera West / Montagem: Maurice Pivar, Edward Cahn / Conselheiro Técnico: Professor R.H. Newlands / Intérpretes: Conrad Veidt (Gwynplaine), Mary Philbin (Dea), Olga Baclanova (Duquesa Josiana), Josephine Crowell (Rainha Anne), George Siegmann (Dr. Hardquannnone), Brandon Hurst (Barkilphedro, o bobo), Sam De Grasse (Rei James), Stuart Holmes (Lord Dirry-Noir), Cesare Gravina (Ursus), Nick De Ruiz (Wapentake), Edgar Norton (Lord Alto Conselheiro), Torben Meyer (“Comprachicos”), Julius Molnar Jr. (Gwynplaine, em criança), Charles Puffy, Frank Puglia, Jack Goodrich, Carmen Costello, Zimbo (Homo, o cão-lobo) Produção: Carl Laemmle (Universal) / Cópia: 35mm, preto e branco, mudo com intertítulos em inglês, legendado eletronicamente em português, 132 minutos, a 22 imagens por segundo / Estreia Mundial: Cinema Central, Nova Iorque, em 27 de Abril de 1928 / Estreia em Portugal: Condes, em 21 de Janeiro de 1930. Acompanhamento ao piano por João Paulo Esteves da Silva _____________________________ Se Paul Leni não tivesse sido um grande realizador, bastaria o trabalho como “cenógrafo” para lhe reservar um lugar na história do cinema, à semelhança de um Mitchell Leisen, um William Cameron Menzies, um Lazare Meerson, num estilo de trabalho cuja tradição ainda hoje se encontra num Dean Tavoularis, por exemplo. -

DOSSIER DE PRESSE Carl Laemmle Présente SYNOPSIS

DOSSIER DE PRESSE Carl Laemmle présente SYNOPSIS En Angleterre, à la fin du XVIIe siècle, le roi Jacques se débarrasse de son ennemi, Conrad Veidt dans le Lord Clancharlie, et vend son jeune fils, Gwynplaine, aux trafiquants d’enfants qui le défigurent. Le garçon s’enfuit et sauve du froid un bébé aveugle, Dea. Tous les deux sont recueillis par Ursus, un forain. Gwynplaine, baptisé « L’Homme qui rit », devient un célèbre comédien ambulant. Le bouffon Barkilphedro découvre L’HOMME son ascendance noble et la dévoile à la reine Anne, qui a succédé au roi Jacques. QUI RIT The Man Who Laughs un film de Paul Leni États-Unis – 1928 – 116 min – visa n°106196 AU CINÉMA LE 9 OCTOBRE à l’occasion du 150ème anniversaire du roman de Victor Hugo EN RESTAURATION 4K Nouvelle orchestration musicale : The Berklee Silent Film Orchestra DISTRIBUTION : PRESSE : MARY-X DISTRIBUTION SF EVENTS cnc n°4438 Tél. : 07 60 29 18 10 308 rue de Charenton 75012 Paris [email protected] Tel. : 01 71 24 23 04 / 06 84 86 40 70 [email protected] NOTES DE PRODUCTION Au début des années 20, le Studio Universal sous la direction de Carl Laemmle Sr connaît deux gros succès avec des films historiques à costumes, Notre-Dame-de- Paris de Wallace Worsley (1923), déjà adapté de Victor Hugo et Le Fantôme de l’Opéra de Rupert Julian (1925) d’après Gaston Leroux. Les deux films avaient pour star Lon Chaney. Universal décide de continuer le filon avec L’Homme qui rit. La pré-production commence en mai 1927. -

By Victor Hugo P

BRUSSELS COMMEMORATES 150 YEARS of ‘LES MISÉRABLES’ SIZED FOR VICTOR HUGO PRESS KIT CONTENTS Brussels commemorates 150 years of ‘Les Misérables’ by Victor Hugo p. 3 On the programme p. 4 Speech by the Ambassador of France in Belgium p. 5 I. Les Misérables, Victor Hugo and Brussels: a strong connection p. 6 II. Walk : in the footsteps of Victor Hugo p. 8 III. Book : In the footsteps of Victor Hugo between Brussels and Paris p. 12 IV. Brusselicious, gastronomic banquet : les Misérables p. 13 V. Events «Les Misérables : 150th anniversary» • Gastronomy p. 15 • Exhibitions p. 15 • Conferences p. 17 • Film p. 19 • Theater p. 20 • Guided tours p. 21 Contacts p. 23 Attachment P. 24 BRUsseLS COMMEMORAtes 150 YEARS Of ‘Les MisÉRABLes’ BY ViCTOR HUGO LES MISÉRABLES IS ONE OF THE GREATEST CLASSICS OF WORLD LITERATURE. THE MASTERPIECE BY VICTOR HUGO ALSO REMAINS VERY POPULAR THANKS TO THE MUSICAL VERSION AND THE MANY MOVIES. Over thirty films have been made of ‘Les Miserables’ and Tom Hooper (The King’s Speech) is currently shooting a new version with a top cast. In March, it is exactly 150 years since ‘Les Misérables’ by Victor Hugo was published. Not in Paris as is often assumed, but in Brussels. The first theatrical performance of ‘Les Misérables’, an adaptation of the book by his son Charles, also took place in Brussels. In addition to these two premieres of ‘Les Misérables’, Brussels played a crucial role in Victor Hugo’s life and his career as a writer and thinker. Closely related to Hugo’s connection with Brussels is also his call for a United States of Europe. -

John Dewey, Maria Montessori, and Objectivist Educational Philosophy During the Postwar Years

73 Historical Studies in Education / Revue d’histoire de l’éducation ARTICLES / ARTICLES “The Ayn Rand School for Tots”: John Dewey, Maria Montessori, and Objectivist Educational Philosophy during the Postwar Years Jason Reid ABSTRACT Objectivism, the libertarian philosophy established by Ayn Rand during the postwar years, has attracted a great deal of attention from philosophers, political scientists, economists, and English professors alike in recent years, but has not received much notice from historians with an interest in education. This article will address that problem by discussing how Rand and her followers established a philosophy of education during the 1960s and 1970s that was based, in part, on vilifying the so-called collectivist ideas of John Dewey and lionizing the so-called individualist ideas of Maria Montessori. Unfortunately, the narrative that emerged during this time seriously misrepresented the ideas of both Dewey and Montessori, resulting in a some- what distorted view of both educators. RÉSUMÉ L’objectivisme, philosophie libertaire conçue par Ayn Rand dans la période de l’après-guerre, a suscitée beaucoup d’attention de la part des philosophes, politologues, économistes et profes- seurs de littérature anglaise, mais rien de tel chez les historiens de l’éducation. Cet article cor- rige cette lacune, en montrant comment durant les années 1960 et 1970 Rand et ses partisans ont établi une philosophie de l’éducation qui s’appuyait, en partie, sur la diffamation des idées prétendues collectivistes de John Dewey et l’idolâtrie de l’individualisme de Maria Montessori. Malheureusement, leurs travaux ont donné une fausse image des idées de Dewey et Montessori et conséquemment ont déformé les théories ces deux éducateurs. -

Comprachicos John Boynton Kaiser

Journal of Criminal Law and Criminology Volume 4 | Issue 2 Article 8 1913 Comprachicos John Boynton Kaiser Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarlycommons.law.northwestern.edu/jclc Part of the Criminal Law Commons, Criminology Commons, and the Criminology and Criminal Justice Commons Recommended Citation John Boynton Kaiser, Comprachicos, 4 J. Am. Inst. Crim. L. & Criminology 247 (May 1913 to March 1914) This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Northwestern University School of Law Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Criminal Law and Criminology by an authorized editor of Northwestern University School of Law Scholarly Commons. THE COMPRACHICOS. JVOE BOYNTON KAISER.' The fertile brain of Victor Hugo-novelist, dramatist, poet, states- man, and sociologist-has given the world numerous studies in criminal sociology which, for human interest, will ever remain classic. Less classic and less well known than many of these studies, yet strangely combining fact and fiction is the second of the two preliminary chapters to L'Homma. Qui Bit wherein Hugo describes at length a people whom he calls by the Spanish compound word Comprachicos, signifying child-buyers. It is a chronicle of crimes and punishments in which strange history is written and cruel and forgotten laws recall to mind ages long since past. Much condensed, though freely employing his own language, Hugo's description of the Comprachicos is given here; the language of no other will suffice. The Comprachicos, or Comprapequefios, were a hideous and nondescript association of wanderers, famous in the 17th century, forgotten in the 18th, unheard of in the 19th. -

Victor Hugo's the Man Who Laughs

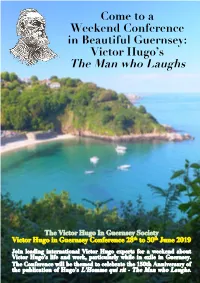

Come to a Weekend Conference in Beautiful Guernsey: Victor Hugo’s The Man who Laughs The Victor Hugo In Guernsey Society Victor Hugo in Guernsey Conference 28th to 30th June 2019 Join leading international Victor Hugo experts for a weekend about Victor Hugo’s life and work, particularly while in exile in Guernsey. The Conference will be themed to celebrate the 150th Anniversary of the publication of Hugo’s L’Homme qui rit - The Man who Laughs. th Victor Hugo Saturday 29 June In Guernsey 9:00 CONFERENCE registration in the Harry Bound Room at Les Côtils Centre. 2019 9:30 BEAUTIFUL INSIDE & OUT, by GÉRARD AUDINET ‘Beautiful inside and out.’ Does the soul have a face? We are all familiar A with the concept of ‘inner beauty,’ but how do artists approach the problem of Conference with L’Homme Qui Rit depicting it? This illustrated talk will reflect on the representations of ugliness Supported by the Guernsey 28th to 30th June and beauty in later arts and media of Victor Hugo’s ‘The Man who Laughs.’ Arts The Victor Hugo In Guernsey Society Commission 10:30 Break for discussion, Coffee or tea. The Victor Hugo In Guernsey Society 11:00 JUSTICE IN THE MAN WHO LAUGHS, by MYRIAM ROMAN Victor Hugo in Guernsey 2019 Conference The representation of justice in ‘The Man who Laughs’ passes through a series of 28th to 30th June 2019 images and myths. The singularity of this novel seems to be to ask the last question of a possible divine injustice through a series of metaphors that project, on the PROGRAMME cosmos, terrifying images of the process and the punishment. -

Polifonia, Cuiabá-MT, V. 23, Nº 34, Jul-Dez., 2016

polifoniaeISSN 22376844 Romantismo e imaginário hugoano. Volubilidade do “Homem que ri” nas artes visuais Romanticism and the hugolian imaginary. The volubility of The man who laughs in visual arts El romantismo y el imaginario de Victor Hugo. La volubilidad de El hombre que ríe en las artes visuales Junia Barreto Universidade de Brasília Resumo O imaginário hugoano é permeado pela figura onírica do caos, que se traduz em excesso, estranhamento, totalidade; elementos que compõem a estética romântica. Excesso e desordem expressos na desfiguração do L’homme qui rit, imagem do caos, figura do amontoamento da massa, mas une force qui va. Texto de tonalidade ímpar, carrega em suas releituras contemporâneas − no romance gráfico ou no cinema − a extemporaneidade ao período romântico e, na expressão do verbo, traço e imagens, o que as une ao romantismo francês, em sua mutabilidade e multiplicidade de sentidos. Da palavra ampla do monstro irrompe a volúpia que desorganiza os sentidos e os gêneros, aproximando e distanciando a estética hugoana do protótipo romântico. Palavras-chave: imaginário hugoano, L’homme qui rit, artes visuais. Abstract The oneiric image of chaos permeates Hugo’s imaginary, translated into excess, strangeness and totality, elements that integrate the romantic aesthetics. Excess and disorder are expressed in the disfigurement of The man who laughs, an image of chaos and accumulation of masses, but “a force that moves”. That text has a unique tone, and its contemporary filmic and graphic novel re-readings are marked by extemporaneous romantic elements, so that they relate to French romanticism in its mutability and multiplicity of senses through words, traces and images. -

Hugo, Baudelaire, Camus, and the Death Penalty

UC Irvine FlashPoints Title Capital Letters: Hugo, Baudelaire, Camus, and the Death Penalty Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/0r30h8pt ISBN 9780810141537 Author Morisi, Eve Publication Date 2020 Peer reviewed eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California Capital Letters The FlashPoints series is devoted to books that consider literature beyond strictly national and disciplinary frameworks, and that are distinguished both by their historical grounding and by their theoretical and conceptual strength. Our books engage theory without losing touch with history and work historically without falling into uncritical positivism. FlashPoints aims for a broad audience within the humanities and the social sciences concerned with moments of cultural emergence and transformation. In a Benjaminian mode, FlashPoints is interested in how liter- ature contributes to forming new constellations of culture and history and in how such formations function critically and politically in the present. Series titles are available online at http://escholarship.org/uc/flashpoints. series editors: Ali Behdad (Comparative Literature and English, UCLA), Edi- tor Emeritus; Judith Butler (Rhetoric and Comparative Literature, UC Berkeley), Editor Emerita; Michelle Clayton (Hispanic Studies and Comparative Literature, Brown University); Edward Dimendberg (Film and Media Studies, Visual Studies, and European Languages and Studies, UC Irvine), Founding Editor; Catherine Gallagher (English, UC Berkeley), Editor Emerita; Nouri Gana (Comparative Lit- erature and Near Eastern Languages and Cultures, UCLA); Susan Gillman (Lit- erature, UC Santa Cruz), Coordinator; Jody Greene (Literature, UC Santa Cruz); Richard Terdiman (Literature, UC Santa Cruz), Founding Editor A complete list of titles begins on p. 267. Capital Letters Hugo, Baudelaire, Camus, and the Death Penalty Ève Morisi northwestern university press | evanston, illinois Northwestern University Press www.nupress.northwestern.edu Copyright © 2020 by Northwestern University Press. -

2017 Film Writings by Roderick Heath @ Ferdy on Films

2017 Film Writings by Roderick Heath @ Ferdy On Films © Text by Roderick Heath. All rights reserved. Contents: Page La La Land (2016) 2 Waxworks (Das Wachsfigurenkabinett, 1924) / The Man Who Laughs (1928) 10 The Manchurian Candidate (1962) 23 Remorques (1941) 35 Shoot the Piano Player (Tirez sur les Pianiste, 1960) 45 Fellini ∙ Satyricon (1969) 54 The Silence of the Lambs (1991) 64 Pink Narcissus (1971) 75 Alien: Covenant (2017) 85 Live and Let Die (1973) / The Spy Who Loved Me (1977) / For Your Eyes Only (1981) 94 T2 Trainspotting (2017) 104 Song To Song (2017) 113 The Lost City of Z (2016) 121 Dunkirk (2017) 130 The Immortal Story (Histoire Immortelle; TV, 1968) 139 Le Samouraï (1967) 162 The Shout (1978) 174 The Ladies Man (1961) 172 Baby Driver (2017) 182 Me, You, Him, Her (Je, Tu, Il, Elle, 1974) / All Night Long (Toute Une Nuit, 1982) 191 The Mummy’s Hand (1940) / The Mummy’s Tomb (1942) / The Mummy’s Ghost (1944) / The Mummy’s Curse (1944) 204 The White Reindeer (Valkoinen Peura, 1953) 223 The Velvet Vampire (1971) 237 Night of the Demon (aka Curse of the Demon, 1957) 245 The Shining (1980) 258 Murder on the Orient Express (2017) 277 Justice League (2017) 287 The Shape of Water (2017) 294 The Disaster Artist (2017) 305 Star Wars: The Last Jedi (2017) 314 2017 Film Writings by Roderick Heath for Ferdy On Films La La Land (2016) Director/Screenwriter: Damien Chazelle By Roderick Heath A clogged LA freeway on a winter‘s day, ―Another Day of Sun,‖ cars backed up for miles on either side. -

Batman the Man Who Laughs Pdf Ebook by Ed Brubaker

Download Batman The Man Who Laughs pdf ebook by Ed Brubaker You're readind a review Batman The Man Who Laughs ebook. To get able to download Batman The Man Who Laughs you need to fill in the form and provide your personal information. Book available on iOS, Android, PC & Mac. Gather your favorite ebooks in your digital library. * *Please Note: We cannot guarantee the availability of this file on an database site. Book Details: Original title: Batman: The Man Who Laughs 144 pages Publisher: DC Comics; 40614th edition (February 3, 2009) Language: English ISBN-10: 9781401216269 ISBN-13: 978-1401216269 ASIN: 1401216269 Product Dimensions:6.7 x 0.2 x 10.2 inches File Format: PDF File Size: 11928 kB Description: Witness Batmans first encounter with The Joker in this volume collecting the graphic novel BATMAN: THE MAN WHO LAUGHS, by Ed Brubaker and Doug Mahnke! This collection also includes DETECTIVE COMICS #784-786, a murder mystery tale guest-starring Green Lantern Alan Scott.... Review: Ed Brubaker takes on Batmans Clown Prince of Crime with another old school style foe the Made of Wood killer in this wonderful Batman comic.NOTE: This is actually two stories with Brubakers take on The Jokers origin story, which is very similar in concept to Alan Moores The Killing Joke, with the difference being the motivations of The Joker. Brubaker... Ebook File Tags: man who laughs pdf, green lantern pdf, made of wood pdf, killing joke pdf, alan scott pdf, dark knight pdf, golden age pdf, joker story pdf, jim gordon pdf, graphic novel pdf, bruce wayne