Tribes of the Montana: an Introduction

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mapa Etnolingüístico Del Perú*

Rev Peru Med Exp Salud Publica. 2010; 27(2): 288-91. SECCIÓN ESPECIAL MAPA ETNOLINGÜÍSTICO DEL PERÚ* Instituto Nacional de Desarrollo de Pueblos Andinos, Amazónicos y Afroperuanos (INDEPA)1 RESUMEN Para brindar una adecuada atención de salud con enfoque intercultural es necesario que el personal de salud conozca la diversidad etnolingüística del Perú, por ello presentamos gráficamente 76 etnias que pertenecen a 16 familias etnolingüísticas y su distribución geográfica en el país. Palabras clave: Población indígena; Grupos étnicos; Diversidad cultural; Peru (fuente: DeCS BIREME). ETHNOLINGUISTIC MAP OF PERU ABSTRACT To provide adequate health care with an intercultural approach is necessary for the health care personnel know the Peruvian ethnolinguistic diversity, so we present 76 ethnic groups that belong to 16 ethnolinguistic families and their geographical distribution on a map of Peru. Key words: Indigenous population; Ethnic groups; Cultural diversity; Peru (source: MeSH NLM). La Constitución Política del Perú 1993 en su Capítulo nativas y hablantes de lenguas indígenas a nivel nacional I sobre los derechos fundamentales de la persona en base al II Censo de Comunidades Indígenas de la humana reconoce que todo peruano tiene derecho a su Amazonía Peruana 2007 y Censos Nacionales 2007: XI identidad étnico-cultural. Pero cuales son las identidades de Población y VI de Vivienda; y también los datos de étnicas culturales y lingüísticas que existen en el país. COfOPRI sobre comunidades campesinas. Para cumplir con este mandato constitucional -

1347871* Cerd/C/Per/18-21

United Nations CERD/C/PER/18-21 International Convention on Distr.: General 25 October 2013 the Elimination of All Forms English of Racial Discrimination Original: Spanish Committee on the Elimination of Racial Discrimination Reports submitted by States parties under article 9 of the Convention Combined eighteenth to twenty-first periodic reports of States parties due in 2012 Peru*, ** [23 April 2013] * This document contains the eighteenth to the twenty-first periodic reports of Peru, due on 29 October 2012. For the fourteenth to the seventeenth periodic reports and the summary records of the meetings at which the Committee considered those reports, see documents CERD/C/PER/14-17 and CERD/C/SR.1934, 1935, 1963 and 1964. ** The present document is being issued without formal editing. GE.13-47871 (EXT) *1347871* CERD/C/PER/18-21 Contents Paragraphs Page I. Introduction............................................................................................................. 1–8 3 II. Information relating to the articles of the Convention ............................................ 9–246 5 Article 1 of the Convention..................................................................................... 9–46 5 A. Definition of racial discrimination in domestic legislation............................. 9–20 5 B. Special measures on behalf of groups of individuals protected by the Convention 21–24 7 C. Ethnic diversity in Peru .................................................................................. 25–46 8 Article 2 of the Convention.................................................................................... -

Sacha Runa Research Foundatior

u-Cultural Survival inc. and Sacha Runa Research Foundatior ART, KNOWLEDGE AND HEALTH Dorothea S. Whitten and Norman E. Whitten, Jr. January 1985 17 r.ultural Survival is a non-profit organization founded in 1972. It is concerned with the fate of eth.. nic minorities and indigenous people throughout the world. Some of these groups face physical ex tinction, for they are seen as impediments to 'development' or 'progress'. For others the destruction is more subtle. If they are not annihilated or swallowed up by the governing majority, they are often decimated by newly introduced diseases and denied their self-determination. They normally are deprived of their lands and their means of livelihood and forced 'o adapt to a dominant society, whose language they may not speak, without possessing the educational, technical, or other skills necessary to make such an adaptation. They therefore are likely to experience permanent poverty, political marginality and cultural alienation. Cultural Survival is thus concerned with human rights issues related to economic development. The organization searches for alternative solutions and works to put those solutions into effect. This involves documenting the destructive aspects of certain types of development and describing alter native, culturally sensitive development projects. Publications, such as the Newsletter and the Special Reports, as well as this Occasional Paper series, are designed to satisfy this need. All papers are intended for a general public as well as for specialized readers, in the hope that the reports will provide basic information as well as research documents for professional work. Cultural Survival's quarterly Newsletter, first published in 1976, documents urgent problems fac ing ethnic minorities and indigenous peoples throughout the world, and publicizes violent infringe ments of human rights as well as more subtle but equally disruptive processes. -

The Corrientes River Case: Indigenous People's

THE CORRIENTES RIVER CASE: INDIGENOUS PEOPLE'S MOBILIZATION IN RESPONSE TO OIL DEVELOPMENT IN THE PERUVIAN AMAZON by GRACIELA MARIA MERCEDES LU A THESIS Presented to the Department of International Studies and the Graduate School of the University of Oregon in partial fulfillment ofthe requirements for the degree of Master of Arts December 2009 ---------------- ii "The Corrientes River Case: Indigenous People's Mobilization in Response to Oil Development in the Peruvian Amazon," a thesis prepared by Graciela Marfa Mercedes Lu in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Master of Arts degree in the Department of International Studies. This thesis has been approved and accepted by: lT.. hiS man.u...s. c. ript .has been approved by the advisor and committee named~ _be'oV\l __~!1_d _~Y--'3:~c~_ard Linton, Dean of the Graduate Scho~I_.. ~ Date Committee in Charge: Derrick Hindery, Chair Anita M. Weiss Carlos Aguirre Accepted by: III © 2009 Graciela Marfa Mercedes Lu IV An Abstract of the Thesis of Graciela M. Lu for the degree of Master of Arts in the Department of International Studies to be taken December 2009 Title: THE CORRIENTES RIVER CASE: INDIGENOUS PEOPLE'S MOBILIZATION IN RESPONSE TO OIL DEVELOPMENT IN THE PERUVIAN AMAZON Approved: Derrick Hindery Economic models applied in Latin America tend to prioritize economic growth heavily based on extractive industries and a power distribution model that affects social equity and respect for human rights. This thesis advances our understanding of the social, political and environmental concerns that influenced the formation of a movement among the Achuar people, in response to oil exploitation activities in the Peruvian Amazon. -

State of the World's Indigenous Peoples

5th Volume State of the World’s Indigenous Peoples Photo: Fabian Amaru Muenala Fabian Photo: Rights to Lands, Territories and Resources Acknowledgements The preparation of the State of the World’s Indigenous Peoples: Rights to Lands, Territories and Resources has been a collaborative effort. The Indigenous Peoples and Development Branch/ Secretariat of the Permanent Forum on Indigenous Issues within the Division for Inclusive Social Development of the Department of Economic and Social Affairs of the United Nations Secretariat oversaw the preparation of the publication. The thematic chapters were written by Mattias Åhrén, Cathal Doyle, Jérémie Gilbert, Naomi Lanoi Leleto, and Prabindra Shakya. Special acknowledge- ment also goes to the editor, Terri Lore, as well as the United Nations Graphic Design Unit of the Department of Global Communications. ST/ESA/375 Department of Economic and Social Affairs Division for Inclusive Social Development Indigenous Peoples and Development Branch/ Secretariat of the Permanent Forum on Indigenous Issues 5TH Volume Rights to Lands, Territories and Resources United Nations New York, 2021 Department of Economic and Social Affairs The Department of Economic and Social Affairs of the United Nations Secretariat is a vital interface between global policies in the economic, social and environmental spheres and national action. The Department works in three main interlinked areas: (i) it compiles, generates and analyses a wide range of economic, social and environ- mental data and information on which States Members of the United Nations draw to review common problems and to take stock of policy options; (ii) it facilitates the negotiations of Member States in many intergovernmental bodies on joint courses of action to address ongoing or emerging global challenges; and (iii) it advises interested Governments on ways and means of translating policy frameworks developed in United Nations conferences and summits into programmes at the country level and, through technical assistance, helps build national capacities. -

Years in the Abanico Del Pastaza - Why We Are Here Stop Theto Degradation of the Planet’S Natural Environment and to Build a Nature

LESSONS LEARNED years10 in + the Abanico del Pastaza Nature, cultures and challenges in the Northern Peruvian Amazon In the Abanico del Pastaza, the largest wetland complex in the Peruvian Amazon, some of the most successful and encouraging conservation stories were written. But, at the same time, these were also some of the toughest and most complex in terms of efforts and sacrifices by its people, in order to restore and safeguard the vital link between the health of the surrounding nature and their own. This short review of stories and lessons, which aims to share the example of the Achuar, Quechua, Kandozi and their kindred peoples with the rest of the world, is dedicated to them. When, in the late nineties, the PREFACE WWF team ventured into the © DIEGO PÉREZ / WWF vast complex of wetlands surrounding the Pastaza river, they did not realize that what they thought to be a “traditional” two-year project would become one of their longest interventions, including major challenges and innovations, both in Peru and in the Amazon basin. The small team, mainly made up of biologists and field technicians, aspired to technically support the creation of a natural protected area to guarantee the conservation of the high local natural diversity, which is also the basis to one of the highest rates of fishing productivity in the Amazon. Soon it became clear that this would not be a routine experience but, on the contrary, it would mark a sort of revolution in the way WWF Patricia León Melgar had addressed conservation in the Amazon until then. -

Annual Report 2015 Annual Report Download

Literacy & Evangelism INTERNATIONAL “...in his word I put my hope.” PSALM 130:5 NIV THE MISSION Literacy & Evangelism International (LEI) equips the Church to share the message of Jesus Christ through the gift of reading. THE STRATEGY We develop Bible-content materials to teach basic reading in local languages and conversational English. We train church leaders and missionaries to use LEI materials for evangelism, discipleship and church planting. We develop partnerships that expand the mission of LEI. “...in his word I put my hope.” PSALM 130:5 NIV 2015 Annual Report 1 MESSAGE FROM THE PRESIDENT: Sid Rice Dear LEI Shareholders: “I wait for the LORD, my whole being waits, and in His word I put my hope.” (Psalm 130:5 NIV) I resonate with the words of the psalmist and, like you, have the privilege of daily reading the words in which we place our hope. However, a billion non-readers around the globe are not able to read for themselves the hope found in the scriptures. Literacy and Evangelism International (LEI) missionaries and global partners continue to open the eyes of non-readers that they too may read of the hope found in God’s word. I am encouraged by Christopher, an eleven- year-old from the Democratic Republic of Congo, who shared, before he could read and write he was “feeling as if I didn’t even exist.” Now, after learning to read using an LEI basic reader, he shares, “God has opened my memory.” Learning to read has given Christopher a new hope. Christopher is not alone; he is one of over twenty thousand new Bible readers created in 2014 through the ministry of LEI. -

Pueblos Indígenas De La Amazonía Peruana

PUEBLOS INDÍGENAS DE LA AMAZONÍA PERUANA Pedro Mayor Aparicio Richard Bodmer PUEBLOS INDÍGENAS DE LA AMAZONÍA PERUANA Pedro Mayor Aparicio Richard E. Bodmer Iquitos – Perú Esta obra ha sido realizada con el apoyo de: FUNDAMAZONÍA © Pedro Mayor Aparicio Pueblos Indígenas de la Amazonía Peruana Fotografías: Biblioteca Amazónica de Iquitos, Centro Teológico de la Amazonía, Carlos Mora, Claudia Ríos, Giuseppe Gagliardi, Cristina López Wong, Jaime Razuri, FORMABIAP, Instituto Lingüístico de Verano y Pedro Mayor Aparicio Revisión de contenidos: Joaquín García (Centro de Estudios Teológicos de la Amazonía) y Manuel Cornejo (Centro Amazónico de Antropología y Aplicación Práctica) Diagramación: Alva Isern Catalao Portada: Composición de fotos de diferentes grupos étnicos de la Amazonía peruana Edición: Centro de Estudios Teológicos de la Amazonía (CETA) Putumayo 355 – Telefs.: 24-1487 / 23-3190 1ra edición, julio del 2009 I.S.B.N.: 978-612-00-0069-4 Código de barras: 9 786120 000694 Hecho el Depósito Legal en la Biblioteca Nacional del Perú: 2009-06504 Pueblos Indígenas de la Amazonía Peruana Autores: Pedro Mayor Aparicio, PhD. Departamento de Sanidad y Anatomía Animales. Universidad Autónoma de Barcelona, España. [email protected] Richard E. Bodmer, PhD. Durrell Institute of Conservation and Ecology (DICE) Department of Anthropology. University of Kent. Canterbury, Kent, United Kingdom [email protected] “Las Naciones Unidas establece que hemos estado sometidos a la opresión, exclusión, marginación, explotación, asimilación forzosa y represión. Se debería incluir en esa definición que nosotros somos felices y vivimos en un territorio inmensamente maravilloso en el que se encuentra nuestro futuro, nuestras leyes y nuestra cosmovisión. Solamente queremos que se entienda cómo hemos conseguido vivir durante tantos años sin ser destruidos. -

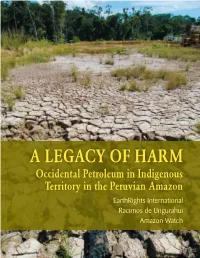

A Legacy of Harm

A LEGACY OF HARM Occidental Petroleum in Indigenous Territory in the Peruvian Amazon EarthRights International Racimos de Ungurahui Amazon Watch EarthRights International • Racimos de Ungurahui • Amazon Watch A LEGACY OF HARM Occidental Petroleum in Indigenous Territory in the Peruvian Amazon “[Oxy] said there wasn’t anything wrong, that the river and the animals and fish were fine. Oxy . didn’t warn us about anything, and this was when Oxy was contaminating our area. Oxy said, ‘we’re just extracting petroleum, we’re not contaminating.’ And so we got no support from Oxy . How am I going to survive? Where am I going to hunt? I want help. How am I going to raise my children?” — Man from Antioquía, May 2006 ABOUT the AUthorS EarthRights International (ERI) is a nonprofit, nongovernmental organization that combines the power of law and the power of people in defense of human rights and the environment. We focus our work at the intersection of human rights and the environment, which we define as earth rights. We specialize in fact-finding, legal actions against perpetrators of earth rights abuses, training for grassroots and community leaders, and advocacy campaigns. Through these strategies, ERI seeks to end earth rights abuses and promote and protect earth rights. ERI has offices in Thailand and Washington, DC. Racimos de Ungurahui is a nonprofit, nongovernmental organization based in Lima, Peru that was founded in 1995 with the mission to contribute to the strengthening and development of the human rights of indigenous Amazonian peoples. Racimos works with the social movement representing the indigenous Amazonian peoples of Peru to strengthen the internal capacity and external capacity of these communities within the context of their multiethnic and multicultural society. -

World Bank Document

IPPI 6 May 2002 STRATEGY TO INCLUDE INDIGENOUS COMMUNITIES IN THE RURAL EDUCATION PROJECT PERU: Rural Education and Teacher Development Project Public Disclosure Authorized I. BACKGROUND 1. LEGAL FRAMEWORK The Peruvian legal framework includes the right of indigenous peoples to education in various legal instances. Peruvian norms in this respect are included in the political constitution of the nation, the General Education Act, the Primary Education Regulations and the recent regulations creating in the National Inter-cultural Bilingual Education Directorate and its Consultative Council. Article 2, ofPeru's Political Constitution mentions that all individuals have the right to preserve their ethnic and cultural identity; that the Peruvian state recognizes and protects ethnic and cultural plurality in the nation; that bilingual and inter-cultural education must be fostered, recognizing each area's characteristics while preserving the various cultural and language manifestations. Public Disclosure Authorized Peru has signedILO'S 169 Agreement(ratified in 1993) recognizing the right of indigenous boys and girls to learn to read and write in their own language, and preserve and develop it. It also recognizes the right of indigenous peoples to be asked about state measures aimed at accomplishing these goals. Likewise, Peru has signed theUniversal Declaration of Human Right4 article 26 of which establishes that educatioii will have as its objective to achieve full individual development, and to strengthen respect for human rights and fundamental -

Uses, Cultural Significance, and Management of Peatlands in The

1 Uses, cultural significance, and management of peatlands in the Peruvian Amazon: 2 implications for conservation 3 Christopher Schulz a, Manuel Martín Brañas b, Cecilia Núñez Pérez b, Margarita Del Águila 4 Villacorta b, Nina Laurie c, Ian T. Lawson c, Katherine H. Roucoux c 5 a Department of Geography, University of Cambridge, Downing Place, Cambridge CB2 3EN, 6 United Kingdom 7 b Amazonian Cultural Diversity and Economy Research Programme, Peruvian Amazon Research 8 Institute (IIAP), Av. José A. Quiñones km 2.5, Iquitos, Peru 9 c School of Geography and Sustainable Development, University of St Andrews, Irvine Building, 10 North Street, St Andrews KY16 9AL, United Kingdom 11 12 Corresponding author: 13 Christopher Schulz ([email protected]) 14 Department of Geography, University of Cambridge, Downing Place, Cambridge CB2 3EN, 15 United Kingdom 16 17 E-mail addresses co-authors: 18 Manuel Martín Brañas: [email protected] 19 Cecilia Núñez Pérez: [email protected] 20 Margarita Del Águila Villacorta: [email protected] 21 Nina Laurie: [email protected] 22 Ian T. Lawson: [email protected] 23 Katherine H. Roucoux: [email protected] 24 25 Acknowledgements 26 The authors would like to thank the communities of Nueva York and Nueva Unión, Loreto, Peru, 27 for agreeing to participate in this research. Further thanks are due to Sam Staddon and Mary 28 Menton for advice on community benefits, Michael Gilmore on participatory mapping, Harry 29 Walker on doing research in Urarina communities, Greta Dargie on peat and peatland 30 characteristics, Eurídice Honorio Coronado, Tim Baker, Jhon del Aguila Pasquel, and Ricardo 31 Zárate on the ecology of the area, and Althea Davies for comments on an earlier version of this 32 manuscript. -

Music, Plants, and Medicine: Lamista Shamanism in the Age of Internationalization

MUSIC, PLANTS, AND MEDICINE: LAMISTA SHAMANISM IN THE AGE OF INTERNATIONALIZATION By CHRISTINA MARIA CALLICOTT A DISSERTATION PRESENTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF THE UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA 2020 © 2020 Christina Maria Callicott In honor of don Leovijildo Ríos Torrejón, who prayed hard over me for three nights and doused me with cigarette smoke, scented waters, and cologne. In so doing, his faith overcame my skepticism and enabled me to salvage my year of fieldwork that, up to that point, had gone terribly awry. In 2019, don Leo vanished into the ethers, never to be seen again. This work is also dedicated to the wonderful women, both Kichwa and mestiza, who took such good care of me during my time in Peru: Maya Arce, Chabu Mendoza, Mama Rosario Tuanama Amasifuen, and my dear friend Neci. ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This dissertation would not have been possible without the kindness and generosity of the Kichwa people of San Martín. I am especially indebted to the people of Yaku Shutuna Rumi, who welcomed me into their homes and lives with great love and affection, and who gave me the run of their community during my stay in El Dorado. I am also grateful to the people of Wayku, who entertained my unannounced visits and inscrutable questioning, as well as the people of the many other communities who so graciously received me and my colleagues for our brief visits. I have received support and encouragement from a great many people during the eight years that it has taken to complete this project.