Usaid/Peru 118/119 Tropical Forest and Biodiversity Analysis

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Lima Junin Pasco Ica Ancash Huanuco Huancavelica Callao Callao Huanuco Cerro De Pasco

/" /" /" /" /" /" /" /" /" /" 78C°U0E'0N"WCA DEL RÍO CULEBRAS 77°0'0"W 76°0'0"W CUENCA DEL RÍO ALTO MARAÑON HUANUCO Colombia CUENCA DEL RÍO HUARMEY /" Ecuador CUENCA DEL RÍO SANTA 10°0'0"S 10°0'0"S TUMBES LORETO HUANUCO PIURA AMAZONAS Brasil LAMBAYEQUECAJAMARCA ANCASH SAN MARTIN LA LICBEURTAED NCA DEL RÍO PACHITEA CUENCA DEL RÍO FORTALEZA ANCASH Peru HUANUCO UCAYALI PASCO COPA ") JUNIN CALLAOLIMA CUENCA DEL RÍO PATIVILCA CUENCA DEL RÍO ALTO HUALLAGA MADRE DE DIOS CAJATAMBO HUANCAVELICA ") CUSCO AYACUCHOAPURIMAC ICA PUNO HUANCAPON ") Bolivia MANAS ") AREQUIPA GORGOR ") MOQUEGUA OYON PARAMONGA ") CERRO DE PASCOPASCO ") PATIVILCA TACNA ") /" Ubicación de la Región Lima BARRANCA AMBAR Chile ") ") SUPE PUERTOSUPE ANDAJES ") ") CAUJUL") PACHANGARA ") ") CUENCA DEL RÍO SUPE NAVAN ") COCHAMARCA ") CUENCA DEL R")ÍO HUAURA ") ")PACCHO SANTA LEONOR 11°0'0"S VEGUETA 11°0'0"S ") LEONCIO PRADO HUAURA ") CUENCA DEL RÍO PERENE ") HUALM")AY ") H")UACHO CALETA DE CARQUIN") SANTA MARIA SAYAN ") PACARAOS IHUARI VEINTISIETE DE NOVIEMBR")E N ") ") ")STA.CRUZ DE ANDAMARCA LAMPIAN ATAVILLOS ALTO ") ") ") CUENCA DEL RÍO CHANCAY - HUARAL ATAVILLOS BAJO ") SUMBILCA HUAROS ") ") CANTA JUNIN ") HUARAL HUAMANTANGA ") ") ") SAN BUENAVENTURA LACHAQUI AUCALLAMA ") CHANCAY") ") CUENCA DEL RÍO MANTARO CUENCA DEL RÍO CH")ILLON ARAHUAY LA")R")AOS ") CARAMPOMAHUANZA STA.ROSA DE QUIVES ") ") CHICLA HUACHUPAMPA ") ") SAN ANTONIO ") SAN PEDRO DE CASTA SAN MATEO ANCON ") ") ") SANTA ROSA ") LIMA ") PUENTE PIEDRACARABAYLLO MATUCANA ") ") CUENCA DEL RÍO RIMAC ") SAN MATEO DE OTAO -

United Nati Ons Limited

UNITED NATI ONS LIMITED ECONOMIC vcn.«A.29 MujrT^H« June 1967 ENGLISH SOCIA*tY1fHlinH|tfmtltlHHimmilllHmtm*llttlfHIHlHimHmittMlllHlnmHmiHhtmumL COUNCIL n ^^ «mawi, «wo» ECONOMIC COMMISSION FOR LATIN AMERICA Santiago, Chile THE INDUSTRIAL DEVELOPMENT OF PERU prepared by the Government of Peru and submitted by the secretariat of the Economic Commission for Latin America Note: This document has been distributed in Spanish for the United Nations International Symposium on Industrial Development, Athens, 29 Novetnberwl9 December 1967, as document ID/CONF,l/R.B.P./3/Add. 13. EXPLANATORY NOTE Resolution 250 (XI) of 14 May 1965, adopted by the Economic Commission for Latin America (ECLA) at its eleventh session, requested the Latin American Governments "to prepare national studies on the present status of their respective industrialization processes for presentation at the regional symposium". With a view to facilitating the task of the officials responsible for the national studies, the ECLA secretariat prepared a guide which was also intended to ensure a certain amount of uniformity in the presentation of the studies with due regard for the specific conditions obtaining in each country. Studies of the industrial development of fourteen countries were submitted to the Latin American Symposium on Industrial Development, held in Santiago, Chile, from 14 to 25 March 1966, under the joint sponsorship of ECLA and the Centre for Industrial Development, and the Symposium requested ECLA to ask the Latin American Governments "to revise, complete and bring up to date the papers presented to the Symposium". The work of editing, revising and expanding the national monographs was completed by the end of 1966 and furthermore, two new studies were prepared. -

Relación De Agencias Que Atenderán De Lunes a Viernes De 8:30 A. M. a 5:30 P

Relación de Agencias que atenderán de lunes a viernes de 8:30 a. m. a 5:30 p. m. y sábados de 9 a. m. a 1 p. m. (con excepción de la Ag. Desaguadero, que no atiende sábados) DPTO. PROVINCIA DISTRITO NOMBRE DIRECCIÓN Avenida Luzuriaga N° 669 - 673 Mz. A Conjunto Comercial Ancash Huaraz Huaraz Huaraz Lote 09 Ancash Santa Chimbote Chimbote Avenida José Gálvez N° 245-250 Arequipa Arequipa Arequipa Arequipa Calle Nicolás de Piérola N°110 -112 Arequipa Arequipa Arequipa Rivero Calle Rivero N° 107 Arequipa Arequipa Cayma Periférica Arequipa Avenida Cayma N° 618 Arequipa Arequipa José Luis Bustamante y Rivero Bustamante y Rivero Avenida Daniel Alcides Carrión N° 217A-217B Arequipa Arequipa Miraflores Miraflores Avenida Mariscal Castilla N° 618 Arequipa Camaná Camaná Camaná Jirón 28 de Julio N° 167 (Boulevard) Ayacucho Huamanga Ayacucho Ayacucho Jirón 28 de Julio N° 167 Cajamarca Cajamarca Cajamarca Cajamarca Jirón Pisagua N° 552 Cusco Cusco Cusco Cusco Esquina Avenida El Sol con Almagro s/n Cusco Cusco Wanchaq Wanchaq Avenida Tomasa Ttito Condemaita 1207 Huancavelica Huancavelica Huancavelica Huancavelica Jirón Francisco de Angulo 286 Huánuco Huánuco Huánuco Huánuco Jirón 28 de Julio N° 1061 Huánuco Leoncio Prado Rupa Rupa Tingo María Avenida Antonio Raymondi N° 179 Ica Chincha Chincha Alta Chincha Jirón Mariscal Sucre N° 141 Ica Ica Ica Ica Avenida Graú N° 161 Ica Pisco Pisco Pisco Calle San Francisco N° 155-161-167 Junín Huancayo Chilca Chilca Avenida 9 De Diciembre N° 590 Junín Huancayo El Tambo Huancayo Jirón Santiago Norero N° 462 Junín Huancayo Huancayo Periférica Huancayo Calle Real N° 517 La Libertad Trujillo Trujillo Trujillo Avenida Diego de Almagro N° 297 La Libertad Trujillo Trujillo Periférica Trujillo Avenida Manuel Vera Enríquez N° 476-480 Avenida Victor Larco Herrera N° 1243 Urbanización La La Libertad Trujillo Victor Larco Herrera Victor Larco Merced Lambayeque Chiclayo Chiclayo Chiclayo Esquina Elías Aguirre con L. -

The Prosopis Juliflora - Prosopis Pallida Complex: a Monograph

DFID DFID Natural Resources Systems Programme The Prosopis juliflora - Prosopis pallida Complex: A Monograph NM Pasiecznik With contributions from P Felker, PJC Harris, LN Harsh, G Cruz JC Tewari, K Cadoret and LJ Maldonado HDRA - the organic organisation The Prosopis juliflora - Prosopis pallida Complex: A Monograph NM Pasiecznik With contributions from P Felker, PJC Harris, LN Harsh, G Cruz JC Tewari, K Cadoret and LJ Maldonado HDRA Coventry UK 2001 organic organisation i The Prosopis juliflora - Prosopis pallida Complex: A Monograph Correct citation Pasiecznik, N.M., Felker, P., Harris, P.J.C., Harsh, L.N., Cruz, G., Tewari, J.C., Cadoret, K. and Maldonado, L.J. (2001) The Prosopis juliflora - Prosopis pallida Complex: A Monograph. HDRA, Coventry, UK. pp.172. ISBN: 0 905343 30 1 Associated publications Cadoret, K., Pasiecznik, N.M. and Harris, P.J.C. (2000) The Genus Prosopis: A Reference Database (Version 1.0): CD ROM. HDRA, Coventry, UK. ISBN 0 905343 28 X. Tewari, J.C., Harris, P.J.C, Harsh, L.N., Cadoret, K. and Pasiecznik, N.M. (2000) Managing Prosopis juliflora (Vilayati babul): A Technical Manual. CAZRI, Jodhpur, India and HDRA, Coventry, UK. 96p. ISBN 0 905343 27 1. This publication is an output from a research project funded by the United Kingdom Department for International Development (DFID) for the benefit of developing countries. The views expressed are not necessarily those of DFID. (R7295) Forestry Research Programme. Copies of this, and associated publications are available free to people and organisations in countries eligible for UK aid, and at cost price to others. Copyright restrictions exist on the reproduction of all or part of the monograph. -

New Age Tourism and Evangelicalism in the 'Last

NEGOTIATING EVANGELICALISM AND NEW AGE TOURISM THROUGH QUECHUA ONTOLOGIES IN CUZCO, PERU by Guillermo Salas Carreño A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Anthropology) in The University of Michigan 2012 Doctoral Committee: Professor Bruce Mannheim, Chair Professor Judith T. Irvine Professor Paul C. Johnson Professor Webb Keane Professor Marisol de la Cadena, University of California Davis © Guillermo Salas Carreño All rights reserved 2012 To Stéphanie ii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This dissertation was able to arrive to its final shape thanks to the support of many throughout its development. First of all I would like to thank the people of the community of Hapu (Paucartambo, Cuzco) who allowed me to stay at their community, participate in their daily life and in their festivities. Many thanks also to those who showed notable patience as well as engagement with a visitor who asked strange and absurd questions in a far from perfect Quechua. Because of the University of Michigan’s Institutional Review Board’s regulations I find myself unable to fully disclose their names. Given their public position of authority that allows me to mention them directly, I deeply thank the directive board of the community through its then president Francisco Apasa and the vice president José Machacca. Beyond the authorities, I particularly want to thank my compadres don Luis and doña Martina, Fabian and Viviana, José and María, Tomas and Florencia, and Francisco and Epifania for the many hours spent in their homes and their fields, sharing their food and daily tasks, and for their kindness in guiding me in Hapu, allowing me to participate in their daily life and answering my many questions. -

Project Appraisal Document (For CEO Endorsement)

THE WORLD BANK/IFC/M.I.G.A. OFFICE MEMORANDUM DATE: December 19, 2000 TO: Mr. Mohamed El-Ashry, CEO/Chairman, GEF FROM: Lars Vidaeus, GEF Executive Coordinator EXTENSION: 34188 SUBJECT: Peru – Indigenous Management of Natural Protected Areas in the Peruvian Amazon Final GEF CEO Endorsement 1. Please find attached the electronic file of the Project Appraisal Document (PAD) for the above-mentioned project for review prior to circulation Council and your final endorsement. This project was approved for Work Program entry at the May 1999 Council meeting under streamlined Council review procedures. 2. The PAD is fully consistent with the objectives and content of the proposal endorsed by Council as part of the May 1999 Work Program. Minor changes regarding implementation emphasis, clustering of components, and financing plan have been introduced during final project preparation and appraisal. Information on these minor modifications, and how GEFSEC, STAP and Council comments received at Work Program entry have been addressed, are outlined below. Implementation Emphasis 3. As conceived at the time of Work Program entry, the project was going to support the creation and management of four new protected areas (Santiago-Comaina, Gueppi and Alto Purus, El Sira) with the participation of indigenous organizations. A fifth area, Pacaya- Samiria, had already been created as a National Reserve, and was to receive project support for improved management, as part of the Government’s effort to place 10% of the Peruvian Amazon under protection. Following Council approval of the Project Brief in May 1999, GOP demonstrated its commitment to project objectives by establishing three new Reserved Zones (Santiago-Comaina, Gueppi and Alto Purus), surpassing the 10% target. -

A Case Study on the Potential of the Multipurpose Prosopis Tree

23 Underutilised crops for famine and poverty alleviation: a case study on the potential of the multipurpose Prosopis tree N.M. Pasiecznik, S.K. Choge, A.B. Rosenfeld and P.J.C. Harris In its native Latin America, the Prosopis tree (also known as Mesquite) has multiple uses as a fuel wood, timber, charcoal, animal fodder and human food. It is also highly drought-resistant, growing under conditions where little else will survive. For this reason, it has been introduced as a pioneer species into the drylands of Africa and Asia over the last two centuries as a means of reclaiming desert lands. However, the knowledge of its uses was not transferred with it, and left in an unmanaged state it has developed into a highly invasive species, where it encroaches on farm land as an impenetrable, thorny thicket. Attempts to eradicate it are proving costly and largely unsuccessful. In 2006, the problem of Prosopis was hitting the headlines on an almost weekly basis in Kenya. Yet amidst calls for its eradication, a pioneering team from the Kenya Forestry Research Institute (KEFRI) and HDRA’s International Programme set out to demonstrate its positive uses. Through a pilot training and capacity building programme in two villages in Baringo District, people living with this tree learned for the first time how to manage and use it to their benefit, both for food security and income generation. Results showed that the pods, milled to flour, would provide a crucial, nutritious food supplement in these famine-prone desert margins. The pods were also used or sold as animal fodder, with the first international order coming from South Africa by the end of the year. -

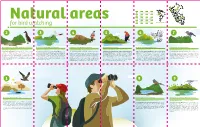

For Bird Watching Areas Additional Information South America

2 9 7 3 4 NPA - Natural Protected Area Peru Habitat 5 6 Best time for birdwatching 1 8 Naturalfor bird watching areas Additional information South America 2 3 4 5 6 7 Los Manglares de Tumbes National Sanctuary Pacaya Samiria National Reserve Pomac Forest Historic Sanctuary Manu National Park Tambopata National Reserve Alto Mayo Protected Forest Bare-throated tiger heron Tigrisoma mexicanum Jabiru Jabiru mycteria Peruvian plantcuer Phytotoma raimondii Andean cock-of-the-rock Rupicola peruvianus Harpy eagle Harpia harpyja Ash-throated antwren Herpsilochmus parkeri Very close to the city of Tumbes, on the northern border of Peru, you will find As the water level starts to decrease in the Amazon lowlands, you will The adventure begins with a visit to the carob trees in the Pomac On the Manu road, between Acjanaco and Tono, and near the famous After a boat trip from Puerto Maldonado and a walk through the Located north of the Alto Mayo rainforest, in an area known as an environment surrounded by mangroves; tall and leafy trees that have given be able to see a great variety of mollusks, amphibians, and birds. The forest. In this 5887-hectare equatorial dry forest you will find a huge Tres Cruces Viewpoint, you will find one of the most famous members of jungle, you will reach a captivating territory with a wealth of flora and Chuquillantas or La Llantería, a mountain ridge can be found. This area the place its name: Los Manglares de Tumbes National Sanctuary. You will visit Pacaya Samiria National Reserve, with a surface area of 2,080,000 carob tree of more than 500 years old, to which the locals aribute the cotingo family: the Andean cock-of-the-rock, which is one of the fauna species. -

A Reappraisal of Phylogenetic Relationships Among Auchenipterid Catfishes of the Subfamily Centromochlinae and Diagnosis of Its Genera (Teleostei: Siluriformes)

ISSN 0097-3157 PROCEEDINGS OF THE ACADEMY OF NATURAL SCIENCES OF PHILADELPHIA 167: 85-146 2020 A reappraisal of phylogenetic relationships among auchenipterid catfishes of the subfamily Centromochlinae and diagnosis of its genera (Teleostei: Siluriformes) LUISA MARIA SARMENTO-SOARES Programa de Pós-Graduação em Biologia Animal, Universidade Federal do Espírito Santo. Prédio Bárbara Weinberg, Campus de Goiabeiras, 29043-900, Vitória, ES, Brasil. http://orcid.org/0000-0002-8621-1794 Laboratório de Ictiologia, Universidade Estadual de Feira de Santana. Av. Transnordestina s/no., Novo Horizonte, 44036-900, Feira de Santana, BA, Brasil Instituto Nossos Riachos, INR, Estrada de Itacoatiara, 356 c4, 24348-095, Niterói, RJ. www.nossosriachos.net E-mail: [email protected] RONALDO FERNANDO MARTINS-PINHEIRO Instituto Nossos Riachos, INR, Estrada de Itacoatiara, 356 c4, 24348-095, Niterói, RJ. www.nossosriachos.net E-mail: [email protected] ABSTRACT.—A hypothesis of phylogenetic relationships is presented for species of the South American catfish subfamily Centromochlinae (Auchenipteridae) based on parsimony analysis of 133 morphological characters in 47 potential ingroup taxa and one outgroup taxon. Of the 48 species previously considered valid in the subfamily, only one, Centromochlus steindachneri, was not evaluated in the present study. The phylogenetic analysis generated two most parsimonious trees, each with 202 steps, that support the monophyly of Centromochlinae composed of five valid genera: Glanidium, Gephyromochlus, Gelanoglanis, Centromochlus and Tatia. Although those five genera form a clade sister to the monotypic Pseudotatia, we exclude Pseudotatia from Centromochlinae. The parsimony analysis placed Glanidium (six species) as the sister group to all other species of Centromochlinae. Gephyromochlus contained a single species, Gephyromochlus leopardus, that is sister to the clade Gelanoglanis (five species) + Centromochlus (eight species). -

Sacha Runa Research Foundatior

u-Cultural Survival inc. and Sacha Runa Research Foundatior ART, KNOWLEDGE AND HEALTH Dorothea S. Whitten and Norman E. Whitten, Jr. January 1985 17 r.ultural Survival is a non-profit organization founded in 1972. It is concerned with the fate of eth.. nic minorities and indigenous people throughout the world. Some of these groups face physical ex tinction, for they are seen as impediments to 'development' or 'progress'. For others the destruction is more subtle. If they are not annihilated or swallowed up by the governing majority, they are often decimated by newly introduced diseases and denied their self-determination. They normally are deprived of their lands and their means of livelihood and forced 'o adapt to a dominant society, whose language they may not speak, without possessing the educational, technical, or other skills necessary to make such an adaptation. They therefore are likely to experience permanent poverty, political marginality and cultural alienation. Cultural Survival is thus concerned with human rights issues related to economic development. The organization searches for alternative solutions and works to put those solutions into effect. This involves documenting the destructive aspects of certain types of development and describing alter native, culturally sensitive development projects. Publications, such as the Newsletter and the Special Reports, as well as this Occasional Paper series, are designed to satisfy this need. All papers are intended for a general public as well as for specialized readers, in the hope that the reports will provide basic information as well as research documents for professional work. Cultural Survival's quarterly Newsletter, first published in 1976, documents urgent problems fac ing ethnic minorities and indigenous peoples throughout the world, and publicizes violent infringe ments of human rights as well as more subtle but equally disruptive processes. -

Global Models of Ant Diversity Suggest Regions Where New Discoveries Are Most Likely Are Under Disproportionate Deforestation Threat

Global models of ant diversity suggest regions where new discoveries are most likely are under disproportionate deforestation threat Benoit Guénard1, Michael D. Weiser, and Robert R. Dunn Department of Biology and the Keck Center for Behavioral Biology, North Carolina State University, Raleigh, NC 27695 Edited* by Edward O. Wilson, Harvard University, Cambridge, MA, and approved March 23, 2012 (received for review August 24, 2011) Most of the described and probably undescribed species on Earth As for other taxa, richness decreased with latitude (e.g., refs. 13 are insects. Global models of species diversity rarely focus on and 14) (Fig. 1) and there were also strong regional effects on the insects and none attempt to address unknown, undescribed magnitude of diversity. African regions were less diverse than diversity. We assembled a database representing about 13,000 would be expected given their latitude (or climate), the reverse of records for ant generic distribution from over 350 regions that the pattern observed for termites (15, 16) and terrestrial mammals cover much of the globe. Based on two models of diversity and (17), although similar to that for vascular plants (5, 18). The 53 endemicity, we identified regions where our knowledge of ant endemic genera were found almost exclusively in tropical regions diversity is most limited, regions we have called “hotspots of dis- that were diverse more generally, with four interesting exceptions covery.” A priori, such regions might be expected to be remote in North Africa, Armenia, Azerbaijan, and South Korea (Fig. 2). and untouched. Instead, we found that the hotspots of discovery Both overall generic diversity and endemic diversity showed are also the regions in which biodiversity is the most threatened a peak in the Oriental region, especially in Borneo, and were also by habitat destruction. -

Evolution of Agroforestry As a Modern Science

Chapter 2 Evolution of Agroforestry as a Modern Science Jagdish C. Dagar and Vindhya P. Tewari Abstract Agroforestry is as old as agriculture itself. Many of the anecdotal agro- forestry practices, which are time tested and evolved through traditional indigenous knowledge, are still being followed in different agroecological zones. The tradi- tional knowledge and the underlying ecological principles concerning indigenous agroforestry systems around the world have been successfully used in designing the improved systems. Many of them such as improved fallows, homegardens, and park systems have evolved as modern agroforestry systems. During past four decades, agroforestry has come of age and begun to attract the attention of the international scientific community, primarily as a means for sustaining agricultural productivity in marginal lands and solving the second-generation problems such as secondary salinization due to waterlogging and contamination of water resources due to the use of excess nitrogen fertilizers and pesticides. Research efforts have shown that most of the degraded areas including saline, waterlogged, and perturbation ecolo- gies like mine spoils and coastal degraded mangrove areas can be made productive by adopting suitable agroforestry techniques involving highly remunerative compo- nents such as plantation-based farming systems, high-value medicinal and aromatic plants, livestock, fishery, poultry, forest and fruit trees, and vegetables. New con- cepts such as integrated farming systems and urban and peri-urban agroforestry have emerged. Consequently, the knowledge base of agroforestry is being expanded at a rapid pace as illustrated by the increasing number and quality of scientific pub- lications of various forms on different aspects of agroforestry. It is both a challenge and an opportunity to scientific community working in this interdisciplinary field.