POPULATION MOBILITY and MIGRANT-VILLAGE TIES a Case Study of Two Villages in East Java by Tukiran a Thesis Submitted in Partial

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Teuku Mohammad Hasan (Sumatra), Soetardjo Kartohadikoesoemo (Jawa Barat), R

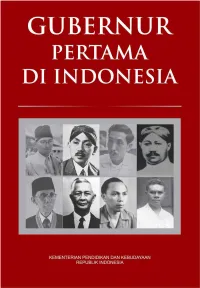

GUBERNUR PERTAMA DI INDONESIA GUBERNUR PERTAMA DI INDONESIA KEMENTERIAN PENDIDIKAN DAN KEBUDAYAAN REPUBLIK INDONESIA GUBERNUR PERTAMA DI INDONESIA PENGARAH Hilmar Farid (Direktur Jenderal Kebudayaan) Triana Wulandari (Direktur Sejarah) NARASUMBER Suharja, Mohammad Iskandar, Mirwan Andan EDITOR Mukhlis PaEni, Kasijanto Sastrodinomo PEMBACA UTAMA Anhar Gonggong, Susanto Zuhdi, Triana Wulandari PENULIS Andi Lili Evita, Helen, Hendi Johari, I Gusti Agung Ayu Ratih Linda Sunarti, Martin Sitompul, Raisa Kamila, Taufik Ahmad SEKRETARIAT DAN PRODUKSI Tirmizi, Isak Purba, Bariyo, Haryanto Maemunah, Dwi Artiningsih Budi Harjo Sayoga, Esti Warastika, Martina Safitry, Dirga Fawakih TATA LETAK DAN GRAFIS Rawan Kurniawan, M Abduh Husain PENERBIT: Direktorat Sejarah Direktorat Jenderal Kebudayaan Kementerian Pendidikan dan Kebudayaan Jalan Jenderal Sudirman, Senayan Jakarta 10270 Tlp/Fax: 021-572504 2017 ISBN: 978-602-1289-72-3 SAMBUTAN Direktur Sejarah Dalam sejarah perjalanan bangsa, Indonesia telah melahirkan banyak tokoh yang kiprah dan pemikirannya tetap hidup, menginspirasi dan relevan hingga kini. Mereka adalah para tokoh yang dengan gigih berjuang menegakkan kedaulatan bangsa. Kisah perjuangan mereka penting untuk dicatat dan diabadikan sebagai bahan inspirasi generasi bangsa kini, dan akan datang, agar generasi bangsa yang tumbuh kelak tidak hanya cerdas, tetapi juga berkarakter. Oleh karena itu, dalam upaya mengabadikan nilai-nilai inspiratif para tokoh pahlawan tersebut Direktorat Sejarah, Direktorat Jenderal Kebudayaan, Kementerian Pendidikan dan Kebudayaan menyelenggarakan kegiatan penulisan sejarah pahlawan nasional. Kisah pahlawan nasional secara umum telah banyak ditulis. Namun penulisan kisah pahlawan nasional kali ini akan menekankan peranan tokoh gubernur pertama Republik Indonesia yang menjabat pasca proklamasi kemerdekaan Indonesia. Para tokoh tersebut adalah Teuku Mohammad Hasan (Sumatra), Soetardjo Kartohadikoesoemo (Jawa Barat), R. Pandji Soeroso (Jawa Tengah), R. -

RIVALITAS ELIT BANGSAWAN DENGAN KELOMPOK TERDIDIK PADA MASA REVOLUSI: Analisis Terhadap Pergulatan Nasionalisme Lokal Di Sulawesi Selatan Menuju NKRI

SEMINAR NASIONAL “Pendidikan Ilmu-Ilmu Sosial Membentuk Karakter Bangsa Dalam Rangka Daya Saing Global” Kerjasama: Fakultas Ilmu Sosial Universitas Negeri Makassar dan Himpunan Sarjana Pendidikan Ilmu-ilmu Sosial Indonesia Grand Clarion Hotel, Makassar, 29 Oktober 2016 RIVALITAS ELIT BANGSAWAN DENGAN KELOMPOK TERDIDIK PADA MASA REVOLUSI: Analisis Terhadap Pergulatan Nasionalisme Lokal di Sulawesi Selatan menuju NKRI Najamuddin Fakultas Ilmu Sosial, Universitas Negeri Makassar ABSTRAK Stratifikasi sosial masyarakat Bugis-Makassar telah memberikan posisi istimewa terhadap kaum bangsawan sebagai elit strategis dari kelompok masyarakat lainnya dalam struktur sosial, dan sebagai pemimpin puncak dalam struktur politik atau struktur kekuasaan. Sementara elit terdidik muncul sebagai elit kedua dalam struktur sosial nasyarakat yang turut berpengaruh dalam dinamika politik lokal di masa revolusi. Ketika kelompok terdidik tampil dalam Pergerakan Nasional di Sulawesi Selatan bersama elit bangsawan, politik kolonial Belanda berhasil mempolarisasi keduanya menjadi bagian yang terpisah menjadi konflik di awal kemerdekaan RI. Kedua kelompok elit tersebut kemudian memilih jalannya masing masing dalam proses perjuangan. Konflik tersebut akhirnya banyak berpengaruh terhadap kelanjutan revolusi di Sulawesi Selatan dan sepanjang berdirinya Negara Indonesia Timur (NIT) hingga menyatakan diri bergabung dengan RI dalan negara kesatuan. Kata kunci: Rivalitas Elit, Bangsawan, Kelompok Terdidik PENDAHULUAN Persiapan menjelang kemerdekaan RI di Sulawesi Selatan -

I I I I 1 I I I I I I I I I I I I

I I ±1 I I 1 I ENVIRONMENTAL HEALTH PROJECT I I I I I I I I I I Picpnrcd [u:. ENVIRONMENTAL HEALTH DIVISION I OFFICE OF HEALTH AND NUTRITION USAit) CLTltL: ~~il [‘J~)LJ~I[iL’!), ~ C!!i~~T~i~[;iL: 1 I GLJ~LJL; L: G)ui~:!P:uq::n~s,FILM SL:upn: rUiL) I ~ tu. U S AL MC~F Ii ‘L t I Liut Ici! u’ \ L I t ~ii f 202.2_936U_13031 I - - -- - - ---I I ENVIRONMENTAL HEALTH PROJECT WASH Reprint: Field Report No. 387 Survey of Pnvate-Sector Participation in Selected Cities in Indonesia J. Woodcock M. Maulana LIBRA~Y R. Thabrani INTERNATIONAL RFFERENCE CfrNT~Ø FOR COMMUNITY WATER SUPPLY ANØ SANITATlONd~ber1993 Co-Sponsored by USAI D/Indonesia Office of Private Enterprise Development, Urban Policy Division (PED/UPD) and the PURSE Steering Committee, composed of BAPPENAS, the Ministry of Home Affairs and -t~~~f Public Works LIBRARYc ~WA~skî~to~ 39g CENTRE FOR OOMMUNI 1 y WA UE~ ~-L’~ AND SAM ATflN ~C) 1 PC U-3’~ ~ 2U.~09AD T;~ 1(~(070) 81 1911 ext. 1411142 1f~J ~ Environmental Health Project Contract No. HRN-5994-C-0O-3036-00, Project No 936-5994 is sponsored by the Bureau for Global Programs, Field Support and Research Office of Health and Nutntion U.S. Agency for International Development Washington, DC 20523 WASH and EHP With the launching of the United Nations International Drinking Water Supply and Sanitation Decade in 1979, the United States Agency for International Development (USAI D) decided to augment and streamline its technical assistance capability in water and sanitation and, in 1980, funded the Water and Sanitation for Health Project (WASH). -

Daftar Arsip Statis Foto Kementerian Penerangan RI : Wilayah DKI Jakarta 1950 1 11 1950.08.15 Sidang BP

ISI INFORMASI ARSIP FOTO BIDANG POLITIK DAN PEMERINTAHAN KURUN KEGIATAN / NO. POSITIF/ NO ISI INFORMASI UKURAN FOTOGRAFER KETERANGAN WAKTU PERISTIWA NEGATIF 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 1 1950.08.15 Sidang Pertama Ketua DPR Sartono sedang membuka sidang pertama Dewan 50001 5R v. Eeden Dewan Perwakilan Perwakilan Rakyat, duduk di sebelahnya, Menteri Rakyat Penerangan M.A. Pellaupessy. 2 Presiden Soekarno menyampaikan pidato di depan Anggota 50003 5R v. Eeden DPR di Gedung Parlemen RIS. [Long Shot Suasana sidang gabungan antara Parlemen RI dan RIS di Jakarta. Dalam rapat tersebut Presiden Soekarno membacakan piagam terbentuknya NKRI dan disetujui oleh anggota sidang.] 3 Presiden Soekarno keluar dari Gedung DPR setelah 50005 5R v. Eeden menghadiri sidang pertama DPR. 4 Perdana Menteri Mohammad Natsir sedang bercakap-cakap 50006 5R v. Eeden dengan Menteri Dalam Negeri Mr. Assaat (berpeci) setelah sidang DPR di Gedung DPR. 5 Lima orang Anggota DPR sedang berunding bersama di 50007 5R v. Eeden sebuah ruangan di Gedung DPR, setelah sidang pertama DPR. 6 Ketua Sementara DPR Dr. Radjiman Wedyodiningrat sedang 50008 5R v. Eeden membuka sidang pertama DPR, di sebelah kanannya duduk Sekretaris. 7 Ketua Sementara DPR Dr. Radjiman Wedyodiningrat sedang 50009 5R v. Eeden membuka sidang pertama DPR, di sebelah kirinya duduk Ketua DPR Mr. Sartono. 8 Suasana ruangan pada saat sidang pertama DPR Negara 50010 5R v. Eeden Kesatuan. 9 [1950.08.15] Sidang BP. KNIP Suasana sidang Badan Pekerja Komite Nasional Indonesia 5R Moh. Irsjad 50021 Pusat (BP. KNIP) di Yogyakarta. 10 Presiden Soekarno sedang berpidato sidang BP. KNIP di 5R 50034 Yogyakarta. -

Proklamasi Dan Dilema Republik Di Indonesia Timur

Seminar Nasional “Proklamasi Kemerdekaan RI di 8 Wilayah” PROKLAMASI DAN DILEMA REPUBLIK DI INDONESIA TIMUR Abd. Rahman Hamid Jurusan Sejarah Univ. Hasanuddin - Makassar Prolog O Proklamasi kemerdekaan 17-8-’45 PPKI menetapkan 8 propinsi (19-8-’45) O Perundingan Linggajati (Maret 1946) wilayah RI: Jawa, Madura, dan Sumatera O Proklamasi terbentuknya NKRI 17-8-’50 O Proklamasi sbg “tonggak” atau “terminal sejarah” Dinamika Lokal sebelum Proklamasi O Gerakan Merah Putih di Sulawesi (tengah) Februari 1942: Gorontalo, Toli-toli, Luwuk, dan Ampana (Poso) O Alih kuasa pemerintahan (sementara), dari Jepang kepada (di) Palu, Poso, Gorontalo. Tapi, tidak di Minahasa. O Sulawesi tenggara bendara merah putih dan lagu Indonesia Raya di distrik Gu (Buton) bersama bendera dan lagu Jepang. Menjelang Proklamasi O Akhir tahun 1944, Bung Karno, Mr. Ahmad Subardjo, dan Mr. Summanang (tiba) di Makassar untuk mempersiapkan kemerdekaan. Bendera merah putih dikibarkan. O Tetapi, kemudian diturunkan oleh Jepang Memberikan motivasi/harapan akan merdekaan O 1 Agustus ‘45, merah putih di Irian (kampung Harapan Jaya) oleh: Marcus Kasiepo, Frans Kasiepo, dll Proklamasi dan Tindak Lanjutnya OProklamasi 17-8-45 di Jakarta ORatulangi bersama Andi Pangerang Pettarani, Andi Sultan Dg. Raja, dan Andi Zainal Abidin ke Jakarta (10-8- ’45). OTerbentuk 8 propinsi, al. Sulawesi (Ratulangi) dan Maluku (Latuharhary). Mendukung Republik (Maluku) O Latuharhary sulit kembali, lalu membentuk pemerintahan di Jakarta (kmd Yogyakarta). Membuka kantor perwakilan di Jawa dan Sumatera membimbing sekitar 30.000 penduduk Maluku di sana. O Perserikatan Pemuda Ambon di Jawa berjuang “membela dan mempertahankan pemerintahan Republik” Semarak Kemerdekaan O Minahasa, merah putih dikibarkan 22 Agustus ‘45 O Pelaut Buton mengibarkan merah putih sepanjang route pelayaran (Sumatera-Jawa-Buton). -

BAB IV LAPORAN HASIL PENELITIAN A. Gambaran Singkat Lokasi Penelitian 1. Sejarah Fakultas Tarbiyah Dan Keguruan Keinginan Untuk

BAB IV LAPORAN HASIL PENELITIAN A. Gambaran Singkat Lokasi Penelitian 1. Sejarah Fakultas Tarbiyah Dan Keguruan Keinginan untuk mendirikan Fakultas Tarbiyah IAIN Antasari Banjarmasin pada dasarnya sudah lama direncanakan oleh tokoh-tokoh pendidikan di Banjarmasin, apalagi dengan semakin banyaknya alumnus dari lembaga pendidikan setingkat SMTA, baik yang berstatus negeri maupun yang swasta, yang ingin melanjutkan pendidikannya ke jenjang yang lebih tinggi atau perguruan tinggi. Di samping itu, kenyataan menunjukkan bahwa guru-guru agama yang berpendidikan tinggi masih sangat langka, baik di sekolah lanjutan pertama (SMP dan MTs) maupun di sekolah lanjutan atas (SMA dan Aliyah). Begitu pula dengan calon-calon dosen baik di IAIN Antasari sendiri maupun di perguruan tinggi umum lainnya dirasakan masih sangat kurang. Kenyataan tersebut ditambah lagi bahwa IAIN Antasari yang berpusat di kota Banjarmasin hanya mempunyai satu fakultas, yaitu Fakultas Syari’ah, sedang Fakultas Tarbiyah sendiri saat itu hanya ada di Barabai sebagai cabang dari IAIN Antasari di Banjarmasin, di samping Fakultas Ushuluddin yang berada di Amuntai. Berdasarkan kenyataan di atas, H. Zafry Zamzam sebagai Rektor IAIN Antasari pada waktu itu merasa perlu agar di Banjarmasin sendiri didirikan pula Fakultas Tarbiyah. Di samping fakultas tersebut dapat melengkapi kekurangan fakultas di IAIN Antasari Banjarmasin, juga diharapkan 50 51 mampu menyahuti berbagai aspirasi dari masyarakat kota Banjarmasin dan sekitarnya yang berkembang saat itu. Pada tanggal 22 September 1965, rektor IAIN Antasari mengeluarkan surat keputusan Nomor 14/BR/IV/1965 tentang pembukaan Fakultas Tarbiyah IAIN Antasari di Banjarmasin. Terbitnya SK Rektor tersebut, juga punya kaitan erat dengan adanya penyerahan Fakultas Publisistik UNISAN (Universitas Islam Kali-mantan) di Banjarmasin untuk dijadikan Fakultas Tarbiyah Banjarmasin. -

Pasang Surut Polarisasi Elit Di Dalam Etnis Bugis Dan Makassar

ISSN : 2302-7517, Vol. 06, No. 02 PASANG SURUT POLARISASI ELIT DI DALAM ETNIS BUGIS DAN MAKASSAR Tidal Polarization in Elite Ethnic and Makassar Bugis Imam Mujahidin Fahmid*), Arya Hadi Dharmawan, Lala M. Kolopaking, Darmawan Salman Departemen Sains Komunikasi dan Pengembangan Masyarakat *) Email : [email protected] Diterima 20 Juni 2011/ Disetujui 11 September 2012 ABSTRACT In the traditional phase, elite ethnic Bugis and Makassar together to develop the concept of political symbols. Symbolic political tradition was contained in a manuscript imaginative; Tomanurung and Kalompoang. A concept to legitimize the authority of the ruler. Socially, the concept Tomanurung then translated by the elite and the masses as a pattern of relationships which are mutually protect; patron-client. In the course of the Bugis and Makassar politics, increasingly weakened Tomanurung concept, beginning with the Islamic presence in the Palace of Gowa, and increasing political desire of the rulers of the kingdom. Seizure of territory and political polarization between ethnic Bugis and Makassar continue escalate, culminating in the 17th century, when the VOC and the White-Bone Palakka of Gowa empire conquered. Since the victory of the Sultanate of Gowa VOC, ethnic Bugis became the dominant ethnic formal power structure. The role of ethnic Bugis somewhat reduced when turning hostile kingdom VOC Bone in 1905. Then the power structure dominated by the palace of Gowa back to the initial phase of the independence of Indonesia. Medieval Old Order until the beginning of reform, ethnic Bugis returned carrying power. Now, through direct election leaders (governors) directly (in the era of regional autonomy), power stage in South Sulawesi, Makassar ethnic recaptured by Gowa. -

At the Time of Sukarno's Visit to Makassar on April 30,1945, the Day After the Emperor's Birthday, an Announcement Was Made

At the time of Sukarno's visit to Makassar on April 30,1945, the day after the Emperor's birthday, an announcement was made that the nationalists' anthem and the flying of their flag had received official Japanese approval. Taken outside the residence of the Naval Governor (front row, left to right): Dr. G. S. Ratulangie, from Manado; Admiral Maeda; Ichiki, in charge of Naval Civil Administration; Mitsuhashi, Naval Area Governor; Sukarno; Tadjuddin Noor; A. Subardjo; (back row) Hayashi Kenichi, who coordinated espionage in prewar Indies and Navy propaganda during the war, and after the war became a novelist; Captain Yanagihara Masuzo, Chief of Political Bureau; Nishijima; Sumanang; Yoshizumi. Photo supplied by Nishijima at time of interview. The Loveday Exchange, A ustralia, 1 9 4 2 : The Japanese N aval Spies Return To Java Greg Poulgrain When Nishijima Shigetada visited Jakarta in 1991, he was greeted as an historical hero. His first arrival there in 1937 had been under the auspices of Japanese Naval Intelligence. With a background in Tokyo of university studies in German language and an early interest in international affairs, particularly the war in China, Nishijima had been recruited by Naval Intelligence to increase Japanese influence in the Nanyang, the region of the Southern Seas. Six months before his arrival in July of 1937, parliamentary debate in Japan had focused on possible Japanese colonization of Netherlands New Guinea. This unexplored territory covered half of the world's largest tropical island—so large that it equaled the combined area of the four main islands of Japan. Advancing Japanese aspirations in the Nanyang, in commerce or in discussions regarding colonization, caused file Dutch govern ment in Batavia to upgrade its surveillance of all who promoted Indonesian nationalism among the colonial subjects. -

Appendix I TRANSLATERY LIST Surah Al-Alaq Verse 1-5 Indonesia Bacalah Dengan (Menyebut) Nama Tuhanmu Yang Menciptakan, Dia Te

Appendix I TRANSLATERY LIST Surah Al-Alaq verse 1-5 Indonesia English Bacalah dengan Recite in the name of (menyebut) nama your Lord who created – Tuhanmu yang menciptakan, Dia telah menciptakan created man from a clot manusia dari 'Alaq, of congealed blood Bacalah, dan Recite, and your Lord is Tuhanmulah yang the most Generous – paling Pemurah, Yang mengajar manusia Who taught by the pen – dengan pena, Dia mengajarkan Taught man what he did kepada manusia apa not know. yang belum diketahuinya Appendix II Reading Test Choose the best answer with marked (X)! Passage One A MISNAMING Mistakes begin with its very name. until recently it was called Mohammedanism by the West, which is not only in accurate but offensive. It is in accurate, Muslims say, because Mohammad didn’t create this religion; God did. Mohammad was merely God’s mouthpiece beyond this the tittle is offensive because it conveys the impression that Islam focuses on a man rather than on God. To name Christianity after Christ is appropriate, they say, for Christians believe that Christ was God. But to call Islam Mohammedanism is like calling Christianity St. Paulism. The proper name of this religion is Islam. Derived from the root s-l-m, which means primarily “peace” but in a secondary sense “Surrender”, its full connotation is “the peace that comes when one’s life is surrendered to God.” Answer the Questions! 1. What is “Mohammedanism” ? a. Mistakes that made by west in called Islam b. The new religion that brought by west c. Another name of Islam d. Muhammad’s religion 2. -

Persaingan Elit Bangsawan Dengan Kelompok Terdidik Pada Masa Revolusi Di Sulawesi Selatan

PERSAINGAN ELIT BANGSAWAN DENGAN KELOMPOK TERDIDIK PADA MASA REVOLUSI DI SULAWESI SELATAN Najamuddin (Dosen Pendidikan Sejarah-FIS Universitas Negeri Makassar) Email: [email protected] ABSTRAK Penelitian ini bertujuan untuk: (1) Mengetahui latar belakang munculnya elit bangsawan dan kelompok terdidik, (2) Mengungkapkan Konflik antara elit bangsawan dengan kelompok terdidik yang berimplikasi pada peran keduanya di Masa Revolusi di Sulawesi Selatan. Metode penelitian yang digunakan dalam penelitian ini adalah metode penelitian sejarah. Tahapan dalam penelitiannya yaitu pemilihan topik, mengumpulkan sumber, kritik sumber, interpretasi, dan historiografi. Hasil penelitian menunjukkan bahwa Stratifikasi sosial masyarakat Bugis-Makassar telah memberikan posisi istimewa terhadap kaum bangsawan sebagai elit strategis dari kelompok masyarakat lainnya dalam struktur sosial, dan sebagai pemimpin puncak dalam struktur politik atau struktur kekuasaan. Ketika elit terdidik tampil dalam Pergerakan Nasional di Sulawesi Selatan bersama elit bangsawan, politik kolonial Belanda berhasil mempolarisasi keduanya menjadi bagian yang terpisah menjadi konflik di awal kemerdekaan RI. Kata Kunci: Elit Bangsawan, Kelompok Terdidik, dan Revolusi di Sulawesi Selatan ABSTRACT This study aims to: (1) Knowing the background of aristocratic elite and educated group, (2) Disclose Conflicts between the aristocratic elite educated group that has implications for the role of both in the Revolution in South Sulawesi. The research method used on this research is history research method. Steps on this research are selecting topic, collecting sources, sources critism, interpreting, and historiography. The results showed that the social stratification of society Bugis- Makassar has given a privileged position against the nobility as a strategic elites of other communities in the social structure, and as a top leader in the political structure or structures of power. -

Culture and Privilege in Capitalist Asia

Downloaded from <arielheryanto.wordpress.com> 6 The years of living luxuriously Identity politics of Indonesia’s new rich Ariel Heryanto Until recently, there were only two quick answers in Indonesia to the question of who constituted the rich. They were unequivocally Westerners and the Chinese. Occasionally one would include top government officials in the list, but at a tier lower than the previous two. Now there can be more diverse answers to the same question, with some hesitation and necessary qualifications. Before 1990 there were more or less fixed stereotypes of Westerners, the Chinese, and top government officials in Indonesian popular culture. Now their public images have undergone significant changes. What follows is an examination of those changes. Obviously economic factors feature in the multiple causes, and diverse directions of these changes. Some consideration of the economic dimension is imperative. However, the bulk of this discussion is more a cultural analysis of economic power, than an economic analysis of cultures. This chapter is therefore about cultural constructions of the rich, which may or may not come close to facts about the economically rich. Westerners and Chinese who personify the rich in Indonesian popular knowledge are cultural constructs. They are fictional. But like most fictional figures, they are neither totally misleading, nor fabricated from pure fantasy.1 Like most fictional works, the popular cultural construction of Westerners and Chinese profiles in Indonesia conveys an important message; and so does the reconstruction of Indonesia’s new rich in the 1990s. The qualifier ‘new’ in the designation of the new rich refers primarily to the first half of the 1990s which is marked by significant prosperity and changes to social identities and relations. -

Perjuangan Tanpa Revolusi: Perspektif Baru Dalam Memahami Kekerasan Periode Revolusi Di Indonesia Timur 1945-1950

PERJUANGAN TANPA REVOLUSI: PERSPEKTIF BARU DALAM MEMAHAMI KEKERASAN PERIODE REVOLUSI DI INDONESIA TIMUR 1945-1950 STRUGGLE WITHOUT REVOLUTION: A NEW PERSPECTIVE IN UNDERSTANDING VIOLENCE OF REVOLUTION PERIOD IN INDONESIA TIMUR 1945-1950 Burhaman Djunedding Fakultas Keguruan dan Ilmu Pendidikan Universitas Pejuang Republik Indonesia Makassar Kampus B. Jalan Baruga Raya Antang Makassar, Sulawesi Selatan 90234 Email: [email protected] Naskah diterima tanggal 27 Agustus 2019, Naskah direvisi tanggal 2 September 2019, Naskah disetujui tanggal 2 Oktober 2019 Abstrak Kajian ini menunjukkan pengalaman masa revolusi di Indonesia Timur yang sangat berbeda dengan pengalaman daerah-daerah lainnya di Indonesia, terutama Jawa dan Sumatera. Di kedua wilayah tersebut, pola perjuangan melawan Belanda adalah perjuangan heroik dengan menggunakan senjata, sebaliknya di Indonesia Timur pola perjuangannya memakai sarana politik yaitu pola perjuangan tanpa revolusi, bahkan karena kondisi sosial, politik dan keamanan yang berbeda maka di kalangan para “pejuang revolusi” di Indonesia Timur akhirnya juga memiliki perbedaan strategi. Meskipun sama-sama merasa republiken, kaum gerilya berjuang dengan bergerilya di pedalaman, sedangkan para politisi yang berada di kota berjuang melalui parlemen di Negara Indonesia Timur (NIT). Penelitian ini menggunakan metode kepustakaan dalam memahami revolusi di Indonesia Timur. Tahapan pertama yang dilakukan adalah penelusuran pustaka guna menelusuri literatur-literatur yang berkaitan dengan kajian ini. Penelusuran literatur