VU Research Portal

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Integration and Conflict in Indonesia's Spice Islands

Volume 15 | Issue 11 | Number 4 | Article ID 5045 | Jun 01, 2017 The Asia-Pacific Journal | Japan Focus Integration and Conflict in Indonesia’s Spice Islands David Adam Stott Tucked away in a remote corner of eastern violence, in 1999 Maluku was divided into two Indonesia, between the much larger islands of provinces – Maluku and North Maluku - but this New Guinea and Sulawesi, lies Maluku, a small paper refers to both provinces combined as archipelago that over the last millennia has ‘Maluku’ unless stated otherwise. been disproportionately influential in world history. Largely unknown outside of Indonesia Given the scale of violence in Indonesia after today, Maluku is the modern name for the Suharto’s fall in May 1998, the country’s Moluccas, the fabled Spice Islands that were continuing viability as a nation state was the only place where nutmeg and cloves grew questioned. During this period, the spectre of in the fifteenth century. Christopher Columbus Balkanization was raised regularly in both had set out to find the Moluccas but mistakenly academic circles and mainstream media as the happened upon a hitherto unknown continent country struggled to cope with economic between Europe and Asia, and Moluccan spices reverse, terrorism, separatist campaigns and later became the raison d’etre for the European communal conflict in the post-Suharto presence in the Indonesian archipelago. The transition. With Yugoslavia’s violent breakup Dutch East India Company Company (VOC; fresh in memory, and not long after the demise Verenigde Oost-indische Compagnie) was of the Soviet Union, Indonesia was portrayed as established to control the lucrative spice trade, the next patchwork state that would implode. -

GENERAL MEETING ~SSEMBLY Friday, 26 November 1954, at 3 P.M

United N ation..'i FIRST COMMIITEE, 730tb GENERAL MEETING ~SSEMBLY Friday, 26 November 1954, at 3 p.m. NINTH SESSION Official Records New York CONTENTS The motion was adopted by 25 votes to 2, with 3 Page abstentions. l.genda item 61: The meeting was suspended at 3.50 p.m. and resumed The question of \Vest Irian (West New Guinea) (con- at 4.20 p.m. tinued) . 417 Mr. Johnson (Canada), Vice-Chairman, took the Chair. Chairman: Mr. Francisco URRUTIA (Colombia). 8. Mr. MUNRO (New Zealand) described the rea "ons why his delegation had been unable to support the inscription of the item on the agenda. Previous United Nations consideration of the question had been AGENDA ITEM 61 in another organ and another context. Although a prima facie case for competence might exist, the new circumstances of the item required consideration of rhe question of West Irian (West New Guinea) the desirability of its inscription on practical as well (A/2694, A/C.l/L.l09) (continued) as legal grounds. After listening to the debate and considering the only draft resolution (AjC.1/L.109) Sayed ABOU-TALEB (Yemen) felt that there before the Committee, his delegation doubted whether .'as no doubt as to the competence of the United any useful purpose would be served by the considera htions to discuss the question of \Vest Irian. The tion of the item. vorld was fortunate to be able to bring such issues 9. New Zealand was intervening in the debate to efore the United Nations and thereby avert further place on record both its friendly feelings towards eterioration in international relations. -

Sultan Zainal Abidin Syah: from the Kingdomcontents of Tidore to the Republic of Indonesia Foreword

TAWARIKH:TAWARIKH: Journal Journal of Historicalof Historical Studies Studies,, VolumeVolume 12(1), 11(2), October April 2020 2020 Volume 11(2), April 2020 p-ISSN 2085-0980, e-ISSN 2685-2284 ABDUL HARIS FATGEHIPON & SATRIONO PRIYO UTOMO Sultan Zainal Abidin Syah: From the KingdomContents of Tidore to the Republic of Indonesia Foreword. [ii] JOHANABSTRACT: WAHYUDI This paper& M. DIEN– using MAJID, the qualitative approach, historical method, and literature review The– discussesHajj in Indonesia Zainal Abidin and Brunei Syah as Darussalam the first Governor in XIX of – WestXX AD: Irian and, at the same time, as Sultan of A ComparisonTidore in North Study Maluku,. [91-102] Indonesia. The results of this study indicate that the political process of the West Irian struggle will not have an important influence in the Indonesian revolution without the MOHAMMADfirmness of the IMAM Tidore FARISI Sultanate, & ARY namely PURWANTININGSIH Sultan Zainal Abidin, Syah. The assertion given by Sultan TheZainal September Abidin 30 Syahth Movement in rejecting and the Aftermath results of in the Indonesian KMB (Konferensi Collective Meja Memory Bundar or Round Table andConference) Revolution: in A 1949, Lesson because for the the Nation KMB. [103-128]sought to separate West Irian from Indonesian territory. The appointment of Zainal Abidin Syah as Sultan took place in Denpasar, Bali, in 1946, and his MARYcoronation O. ESERE, was carried out a year later in January 1947 in Soa Sio, Tidore. Zainal Abidin Syah was Historicalas the first Overview Governor of ofGuidance West Irian, and which Counselling was installed Practices on 23 inrd NigeriaSeptember. [129-142] 1956. Ali Sastroamidjojo’s Cabinet formed the Province of West Irian, whose capital was located in Soa Sio. -

INDONESIA 1942–1950 Praise For

WILLIAM J. RUST THE MASK of NEUTRALITY THE UNITED STATES AND D E COL O NIZ ATIO N IN INDONESIA 1942–1950 Praise for The Mask of Neutrality: The United States and Decolonization in Indonesia, 1942–1950 “William Rust once again reminds us that we can find no better guide to the labyrinthine origins of America’s tragic entanglements in Southeast Asia. Deeply researched in a broad spectrum of archives and uncovering a range of hitherto little known or even unknown intelligence activities, The Mask of Neutrality explores the twists and turns of the US posture toward the decolonization of Indonesia with insight, nuance, and historical sensibility. A sobering account, it will remain the go-to history for years to come.” ¾ Richard Immerman, Temple University “William Rust likes to say he prefers origin stories. The Mask of Neutrality is just that¾for the nation of Indonesia, emerging from its centuries as a Dutch colony. In a history eerily similar to that of Vietnam¾and, where the author shows us, Dean Rusk had a ringside seat and ought to have learned the lessons¾nationalists have gained the heart of the nation, but Dutch colonialists negotiate insincerely, then fight, to change that. Rust delivers a deep tale of World War II anxieties, inter-allied intrigues, American doubts and internal squabbles, CIA machinations. Its predecessor agency, the OSS, even resorts to kidnapping in order to recruit agents. This is a splendid account, a detailed diplomatic history, and an eye-opening peek at a significant piece of history. Everyone interested in America’s role in the world should read The Mask of Neutrality.” ¾ John Prados, author of Safe for Democracy: The Secret Wars of the CIA “William Rust has done it again. -

From Paradise Lost to Promised Land: Christianity and the Rise of West

School of History & Politics & Centre for Asia Pacific Social Transformation Studies (CAPSTRANS) University of Wollongong From Paradise Lost to Promised Land Christianity and the Rise of West Papuan Nationalism Susanna Grazia Rizzo A Thesis submitted for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy (History) of the University of Wollongong 2004 “Religion (…) constitutes the universal horizon and foundation of the nation’s existence. It is in terms of religion that a nation defines what it considers to be true”. G. W. F. Hegel, Lectures on the of Philosophy of World History. Abstract In 1953 Aarne Koskinen’s book, The Missionary Influence as a Political Factor in the Pacific Islands, appeared on the shelves of the academic world, adding further fuel to the longstanding debate in anthropological and historical studies regarding the role and effects of missionary activity in colonial settings. Koskinen’s finding supported the general view amongst anthropologists and historians that missionary activity had a negative impact on non-Western populations, wiping away their cultural templates and disrupting their socio-economic and political systems. This attitude towards mission activity assumes that the contemporary non-Western world is the product of the ‘West’, and that what the ‘Rest’ believes and how it lives, its social, economic and political systems, as well as its values and beliefs, have derived from or have been implanted by the ‘West’. This postulate has led to the denial of the agency of non-Western or colonial people, deeming them as ‘history-less’ and ‘nation-less’: as an entity devoid of identity. But is this postulate true? Have the non-Western populations really been passive recipients of Western commodities, ideas and values? This dissertation examines the role that Christianity, the ideology of the West, the religion whose values underlies the semantics and structures of modernisation, has played in the genesis and rise of West Papuan nationalism. -

The Making of Middle Indonesia Verhandelingen Van Het Koninklijk Instituut Voor Taal-, Land- En Volkenkunde

The Making of Middle Indonesia Verhandelingen van het Koninklijk Instituut voor Taal-, Land- en Volkenkunde Edited by Rosemarijn Hoefte KITLV, Leiden Henk Schulte Nordholt KITLV, Leiden Editorial Board Michael Laffan Princeton University Adrian Vickers Sydney University Anna Tsing University of California Santa Cruz VOLUME 293 Power and Place in Southeast Asia Edited by Gerry van Klinken (KITLV) Edward Aspinall (Australian National University) VOLUME 5 The titles published in this series are listed at brill.com/vki The Making of Middle Indonesia Middle Classes in Kupang Town, 1930s–1980s By Gerry van Klinken LEIDEN • BOSTON 2014 This is an open access title distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution‐ Noncommercial 3.0 Unported (CC‐BY‐NC 3.0) License, which permits any non‐commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited. The realization of this publication was made possible by the support of KITLV (Royal Netherlands Institute of Southeast Asian and Caribbean Studies). Cover illustration: PKI provincial Deputy Secretary Samuel Piry in Waingapu, about 1964 (photo courtesy Mr. Ratu Piry, Waingapu). Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Klinken, Geert Arend van. The Making of middle Indonesia : middle classes in Kupang town, 1930s-1980s / by Gerry van Klinken. pages cm. -- (Verhandelingen van het Koninklijk Instituut voor Taal-, Land- en Volkenkunde, ISSN 1572-1892; volume 293) Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-90-04-26508-0 (hardback : acid-free paper) -- ISBN 978-90-04-26542-4 (e-book) 1. Middle class--Indonesia--Kupang (Nusa Tenggara Timur) 2. City and town life--Indonesia--Kupang (Nusa Tenggara Timur) 3. -

Ritual and Reflexes of Lost Sovereignty in Sikka, a Regency of Flores in Eastern Indonesia

E.D. LEWIS Ritual and reflexes of lost sovereignty in Sikka, a regency of Flores in eastern Indonesia In 1993 some among the Sikkanese population of the town of Maumere on the north coast of Flores in eastern Indonesia attended a ritual to reconcile the members of two branches of the family of the rajas of Sikka, a dynasty that had once ruled the district.1 The two branches had fallen out over differences in opinion about the last succession to the office of raja a few years before the end of the rajadom in the late 1950s. A description of the ritual, which was conducted in an urban rather than a village setting, and an analysis of the performance demonstrate much about the persistence of elements of the old Sikkanese religion in modern Sikkanese society. The contemporary Sikkanese are Christians and the regency of Sikka is part of the modern Indonesian nation-state. Thus the performance of a ritual of the old Sikkanese religion in urban Maumere is sufficiently interesting to merit attention. But when seen in relation to events that unfolded during the final years of the rajadom of Sikka, the ritual reveals the continuing importance of ideas about Sikka’s past sovereignty in contemporary Sikkanese affairs and suggests that conceptions of polity, rulership, and the idea of Sikkanese sovereignty are still in force two generations after the era of Sikkanese political sovereignty ended. 1 This essay was conceived while I was a visitor at the Institutt for Sosialantropologi of the University of Bergen, Norway, from 15 January to 15 July 2004, and was completed in draft during a season of fieldwork on Flores in January–February 2005. -

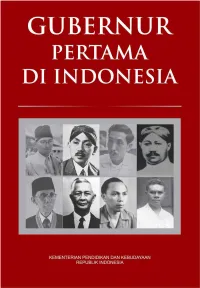

Teuku Mohammad Hasan (Sumatra), Soetardjo Kartohadikoesoemo (Jawa Barat), R

GUBERNUR PERTAMA DI INDONESIA GUBERNUR PERTAMA DI INDONESIA KEMENTERIAN PENDIDIKAN DAN KEBUDAYAAN REPUBLIK INDONESIA GUBERNUR PERTAMA DI INDONESIA PENGARAH Hilmar Farid (Direktur Jenderal Kebudayaan) Triana Wulandari (Direktur Sejarah) NARASUMBER Suharja, Mohammad Iskandar, Mirwan Andan EDITOR Mukhlis PaEni, Kasijanto Sastrodinomo PEMBACA UTAMA Anhar Gonggong, Susanto Zuhdi, Triana Wulandari PENULIS Andi Lili Evita, Helen, Hendi Johari, I Gusti Agung Ayu Ratih Linda Sunarti, Martin Sitompul, Raisa Kamila, Taufik Ahmad SEKRETARIAT DAN PRODUKSI Tirmizi, Isak Purba, Bariyo, Haryanto Maemunah, Dwi Artiningsih Budi Harjo Sayoga, Esti Warastika, Martina Safitry, Dirga Fawakih TATA LETAK DAN GRAFIS Rawan Kurniawan, M Abduh Husain PENERBIT: Direktorat Sejarah Direktorat Jenderal Kebudayaan Kementerian Pendidikan dan Kebudayaan Jalan Jenderal Sudirman, Senayan Jakarta 10270 Tlp/Fax: 021-572504 2017 ISBN: 978-602-1289-72-3 SAMBUTAN Direktur Sejarah Dalam sejarah perjalanan bangsa, Indonesia telah melahirkan banyak tokoh yang kiprah dan pemikirannya tetap hidup, menginspirasi dan relevan hingga kini. Mereka adalah para tokoh yang dengan gigih berjuang menegakkan kedaulatan bangsa. Kisah perjuangan mereka penting untuk dicatat dan diabadikan sebagai bahan inspirasi generasi bangsa kini, dan akan datang, agar generasi bangsa yang tumbuh kelak tidak hanya cerdas, tetapi juga berkarakter. Oleh karena itu, dalam upaya mengabadikan nilai-nilai inspiratif para tokoh pahlawan tersebut Direktorat Sejarah, Direktorat Jenderal Kebudayaan, Kementerian Pendidikan dan Kebudayaan menyelenggarakan kegiatan penulisan sejarah pahlawan nasional. Kisah pahlawan nasional secara umum telah banyak ditulis. Namun penulisan kisah pahlawan nasional kali ini akan menekankan peranan tokoh gubernur pertama Republik Indonesia yang menjabat pasca proklamasi kemerdekaan Indonesia. Para tokoh tersebut adalah Teuku Mohammad Hasan (Sumatra), Soetardjo Kartohadikoesoemo (Jawa Barat), R. Pandji Soeroso (Jawa Tengah), R. -

The Indonesian Struggle for Independence 1945 – 1949

The Indonesian struggle for Independence 1945 – 1949 Excessive violence examined University of Amsterdam Bastiaan van den Akker Student number: 11305061 MA Holocaust and Genocide Studies Date: 28-01-2021 Supervisor: Prof. Dr. Ugur Ümit Üngör Second Reader: Dr. Hinke Piersma Abstract The pursuit of a free Indonesian state was already present during Dutch rule. The Japanese occupation and subsequent years ensured that this pursuit could become a reality. This thesis examines the last 4 years of the Indonesian struggle for independence between 1945 and 1949. Excessive violence prevailed during these years, both the Indonesians and the Dutch refused to relinquish hegemony on the archipelago resulting in around 160,000 casualties. The Dutch tried to forget the war of Indonesian Independence in the following years. However, whistleblowers went public in the 1960’s, resulting in further examination into the excessive violence. Eventually, the Netherlands seems to have come to terms with its own past since the first formal apologies by a Dutch representative have been made in 2005. King Willem-Alexander made a formal apology on behalf of the Crown in 2020. However, high- school education is still lacking in educating students on these sensitive topics. This thesis also discusses the postwar years and the public debate on excessive violence committed by both sides. The goal of this thesis is to inform the public of the excessive violence committed by Dutch and Indonesian soldiers during the Indonesian struggle for Independence. 1 Index Introduction -

The Dutch Strategic and Operational Approach in the Indonesian War of Independence, 1945– 1949

Scientia Militaria, South African Journal of Military Studies, Vol 46, Nr 2, 2018. doi: 10.5787/46-2-1237 THE DUTCH STRATEGIC AND OPERATIONAL APPROACH IN THE INDONESIAN WAR OF INDEPENDENCE, 1945– 1949 Leopold Scholtz1 North-West University Abstract The Indonesian War of Independence (1945–1949) and the Dutch attempt to combat the insurgency campaign by the Indonesian nationalists provides an excellent case study of how not to conduct a counter-insurgency war. In this article, it is reasoned that the Dutch security strategic objective – a smokescreen of autonomy while keeping hold of political power – was unrealistic. Their military strategic approach was very deficient. They approached the war with a conventional war mind- set, thinking that if they could merely reoccupy the whole archipelago and take the nationalist leaders prisoner, that it would guarantee victory. They also mistreated the indigenous population badly, including several mass murders and other war crimes, and ensured that the population turned against them. There was little coordination between the civilian and military authorities. Two conventional mobile operations, while conducted professionally, actually enlarged the territory to be pacified and weakened the Dutch hold on the country. By early 1949, it was clear that the Dutch had lost the war, mainly because the Dutch made a series of crucial mistakes, such as not attempting to win the hearts and minds of the local population. In addition, the implacable opposition by the United States made their war effort futile. Keywords: Indonesian War of Independence, Netherlands, insurgency, counter- insurgency, police actions, strategy, operations, tactics, Dutch army Introduction Analyses of counter-insurgency operations mostly concentrate on the well- known conflicts – the French and Americans in Vietnam, the British in Malaya and Kenya, the French in Algeria, the Portuguese in Angola and Mozambique, the Ian Smith government in Rhodesia, the South Africans in Namibia, et cetera. -

Splitting, Splitting and Splitting Again a Brief History of the Development of Regional Government in Indonesia Since Independence

Bijdragen tot de Taal-, Land- en Volkenkunde Vol. 167, no. 1 (2011), pp. 31-59 URL: http://www.kitlv-journals.nl/index.php/btlv URN:NBN:NL:UI:10-1-100898 Copyright: content is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 3. -

Rijksuniversiteit Groningen

Decolonization and the Military: the Case of the Netherlands A Study in Political Reaction Rob Kroes, University of Amsterdam I Introduction *) When taken together, title and subtitle of this paper may seem to suggest, but certainly are not meant to implicate, that only m ilitary circles are apt to engage in right-wing political activism. On the contrary, this paper tries to indicate what specific groups within the armed forces of the Netherlands had an interest in opposing Indonesian independence, and what strategic alliances they engaged in with right- w in g c ivilian circles. In that sense, the subject of the paper is rather “underground” civil-military relations, as they exist alongside the level of institutionalized civil- m ilitary relations. Our analysis starts from a systematic theoretical perspective which, on the one hand, is intended to specify our expectations as to what interest groups within and without the m ilitary tended to align in opposing Indonesian independence and, on the other hand, to broadly characterize the options open to such coalitions for influencing the course of events either in the Netherlands or in the Dutch East Indies. II The theoretical perspective In two separate papers2) a process model of conflict and radicalism has been developed and further specified to serve as a basis for the study of m ilitary intervention in domestic politics. The model, although social-psychological in its emphasis on the *) I want to express my gratitude to the following persons who have been willing to respond to my request to discuss the role of the military during the Indonesian crisis: Messrs.