Rijksuniversiteit Groningen

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Integration and Conflict in Indonesia's Spice Islands

Volume 15 | Issue 11 | Number 4 | Article ID 5045 | Jun 01, 2017 The Asia-Pacific Journal | Japan Focus Integration and Conflict in Indonesia’s Spice Islands David Adam Stott Tucked away in a remote corner of eastern violence, in 1999 Maluku was divided into two Indonesia, between the much larger islands of provinces – Maluku and North Maluku - but this New Guinea and Sulawesi, lies Maluku, a small paper refers to both provinces combined as archipelago that over the last millennia has ‘Maluku’ unless stated otherwise. been disproportionately influential in world history. Largely unknown outside of Indonesia Given the scale of violence in Indonesia after today, Maluku is the modern name for the Suharto’s fall in May 1998, the country’s Moluccas, the fabled Spice Islands that were continuing viability as a nation state was the only place where nutmeg and cloves grew questioned. During this period, the spectre of in the fifteenth century. Christopher Columbus Balkanization was raised regularly in both had set out to find the Moluccas but mistakenly academic circles and mainstream media as the happened upon a hitherto unknown continent country struggled to cope with economic between Europe and Asia, and Moluccan spices reverse, terrorism, separatist campaigns and later became the raison d’etre for the European communal conflict in the post-Suharto presence in the Indonesian archipelago. The transition. With Yugoslavia’s violent breakup Dutch East India Company Company (VOC; fresh in memory, and not long after the demise Verenigde Oost-indische Compagnie) was of the Soviet Union, Indonesia was portrayed as established to control the lucrative spice trade, the next patchwork state that would implode. -

GENERAL MEETING ~SSEMBLY Friday, 26 November 1954, at 3 P.M

United N ation..'i FIRST COMMIITEE, 730tb GENERAL MEETING ~SSEMBLY Friday, 26 November 1954, at 3 p.m. NINTH SESSION Official Records New York CONTENTS The motion was adopted by 25 votes to 2, with 3 Page abstentions. l.genda item 61: The meeting was suspended at 3.50 p.m. and resumed The question of \Vest Irian (West New Guinea) (con- at 4.20 p.m. tinued) . 417 Mr. Johnson (Canada), Vice-Chairman, took the Chair. Chairman: Mr. Francisco URRUTIA (Colombia). 8. Mr. MUNRO (New Zealand) described the rea "ons why his delegation had been unable to support the inscription of the item on the agenda. Previous United Nations consideration of the question had been AGENDA ITEM 61 in another organ and another context. Although a prima facie case for competence might exist, the new circumstances of the item required consideration of rhe question of West Irian (West New Guinea) the desirability of its inscription on practical as well (A/2694, A/C.l/L.l09) (continued) as legal grounds. After listening to the debate and considering the only draft resolution (AjC.1/L.109) Sayed ABOU-TALEB (Yemen) felt that there before the Committee, his delegation doubted whether .'as no doubt as to the competence of the United any useful purpose would be served by the considera htions to discuss the question of \Vest Irian. The tion of the item. vorld was fortunate to be able to bring such issues 9. New Zealand was intervening in the debate to efore the United Nations and thereby avert further place on record both its friendly feelings towards eterioration in international relations. -

Sultan Zainal Abidin Syah: from the Kingdomcontents of Tidore to the Republic of Indonesia Foreword

TAWARIKH:TAWARIKH: Journal Journal of Historicalof Historical Studies Studies,, VolumeVolume 12(1), 11(2), October April 2020 2020 Volume 11(2), April 2020 p-ISSN 2085-0980, e-ISSN 2685-2284 ABDUL HARIS FATGEHIPON & SATRIONO PRIYO UTOMO Sultan Zainal Abidin Syah: From the KingdomContents of Tidore to the Republic of Indonesia Foreword. [ii] JOHANABSTRACT: WAHYUDI This paper& M. DIEN– using MAJID, the qualitative approach, historical method, and literature review The– discussesHajj in Indonesia Zainal Abidin and Brunei Syah as Darussalam the first Governor in XIX of – WestXX AD: Irian and, at the same time, as Sultan of A ComparisonTidore in North Study Maluku,. [91-102] Indonesia. The results of this study indicate that the political process of the West Irian struggle will not have an important influence in the Indonesian revolution without the MOHAMMADfirmness of the IMAM Tidore FARISI Sultanate, & ARY namely PURWANTININGSIH Sultan Zainal Abidin, Syah. The assertion given by Sultan TheZainal September Abidin 30 Syahth Movement in rejecting and the Aftermath results of in the Indonesian KMB (Konferensi Collective Meja Memory Bundar or Round Table andConference) Revolution: in A 1949, Lesson because for the the Nation KMB. [103-128]sought to separate West Irian from Indonesian territory. The appointment of Zainal Abidin Syah as Sultan took place in Denpasar, Bali, in 1946, and his MARYcoronation O. ESERE, was carried out a year later in January 1947 in Soa Sio, Tidore. Zainal Abidin Syah was Historicalas the first Overview Governor of ofGuidance West Irian, and which Counselling was installed Practices on 23 inrd NigeriaSeptember. [129-142] 1956. Ali Sastroamidjojo’s Cabinet formed the Province of West Irian, whose capital was located in Soa Sio. -

The Making of Middle Indonesia Verhandelingen Van Het Koninklijk Instituut Voor Taal-, Land- En Volkenkunde

The Making of Middle Indonesia Verhandelingen van het Koninklijk Instituut voor Taal-, Land- en Volkenkunde Edited by Rosemarijn Hoefte KITLV, Leiden Henk Schulte Nordholt KITLV, Leiden Editorial Board Michael Laffan Princeton University Adrian Vickers Sydney University Anna Tsing University of California Santa Cruz VOLUME 293 Power and Place in Southeast Asia Edited by Gerry van Klinken (KITLV) Edward Aspinall (Australian National University) VOLUME 5 The titles published in this series are listed at brill.com/vki The Making of Middle Indonesia Middle Classes in Kupang Town, 1930s–1980s By Gerry van Klinken LEIDEN • BOSTON 2014 This is an open access title distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution‐ Noncommercial 3.0 Unported (CC‐BY‐NC 3.0) License, which permits any non‐commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited. The realization of this publication was made possible by the support of KITLV (Royal Netherlands Institute of Southeast Asian and Caribbean Studies). Cover illustration: PKI provincial Deputy Secretary Samuel Piry in Waingapu, about 1964 (photo courtesy Mr. Ratu Piry, Waingapu). Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Klinken, Geert Arend van. The Making of middle Indonesia : middle classes in Kupang town, 1930s-1980s / by Gerry van Klinken. pages cm. -- (Verhandelingen van het Koninklijk Instituut voor Taal-, Land- en Volkenkunde, ISSN 1572-1892; volume 293) Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-90-04-26508-0 (hardback : acid-free paper) -- ISBN 978-90-04-26542-4 (e-book) 1. Middle class--Indonesia--Kupang (Nusa Tenggara Timur) 2. City and town life--Indonesia--Kupang (Nusa Tenggara Timur) 3. -

The Indonesian Struggle for Independence 1945 – 1949

The Indonesian struggle for Independence 1945 – 1949 Excessive violence examined University of Amsterdam Bastiaan van den Akker Student number: 11305061 MA Holocaust and Genocide Studies Date: 28-01-2021 Supervisor: Prof. Dr. Ugur Ümit Üngör Second Reader: Dr. Hinke Piersma Abstract The pursuit of a free Indonesian state was already present during Dutch rule. The Japanese occupation and subsequent years ensured that this pursuit could become a reality. This thesis examines the last 4 years of the Indonesian struggle for independence between 1945 and 1949. Excessive violence prevailed during these years, both the Indonesians and the Dutch refused to relinquish hegemony on the archipelago resulting in around 160,000 casualties. The Dutch tried to forget the war of Indonesian Independence in the following years. However, whistleblowers went public in the 1960’s, resulting in further examination into the excessive violence. Eventually, the Netherlands seems to have come to terms with its own past since the first formal apologies by a Dutch representative have been made in 2005. King Willem-Alexander made a formal apology on behalf of the Crown in 2020. However, high- school education is still lacking in educating students on these sensitive topics. This thesis also discusses the postwar years and the public debate on excessive violence committed by both sides. The goal of this thesis is to inform the public of the excessive violence committed by Dutch and Indonesian soldiers during the Indonesian struggle for Independence. 1 Index Introduction -

Splitting, Splitting and Splitting Again a Brief History of the Development of Regional Government in Indonesia Since Independence

Bijdragen tot de Taal-, Land- en Volkenkunde Vol. 167, no. 1 (2011), pp. 31-59 URL: http://www.kitlv-journals.nl/index.php/btlv URN:NBN:NL:UI:10-1-100898 Copyright: content is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 3. -

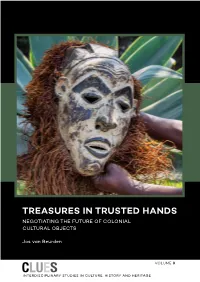

Treasures in Trusted Hands

Van Beurden Van TREASURES IN TRUSTED HANDS This pioneering study charts the one-way traffic of cultural “A monumental work of and historical objects during five centuries of European high quality.” colonialism. It presents abundant examples of disappeared Dr. Guido Gryseels colonial objects and systematises these into war booty, (Director-General of the Royal confiscations by missionaries and contestable acquisitions Museum for Central Africa in by private persons and other categories. Former colonies Tervuren) consider this as a historical injustice that has not been undone. Former colonial powers have kept most of the objects in their custody. In the 1970s the Netherlands and Belgium “This is a very com- HANDS TRUSTED IN TREASURES returned objects to their former colonies Indonesia and mendable treatise which DR Congo; but their number was considerably smaller than has painstakingly and what had been asked for. Nigeria’s requests for the return of with detachment ex- plored the emotive issue some Benin objects, confiscated by British soldiers in 1897, of the return of cultural are rejected. objects removed in colo- nial times to the me- As there is no consensus on how to deal with colonial objects, tropolis. He has looked disputes about other categories of contestable objects are at the issues from every analysed. For Nazi-looted art-works, the 1998 Washington continent with clarity Conference Principles have been widely accepted. Although and perspicuity.” non-binding, they promote fair and just solutions and help people to reclaim art works that they lost involuntarily. Prof. Folarin Shyllon (University of Ibadan) To promote solutions for colonial objects, Principles for Dealing with Colonial Cultural and Historical Objects are presented, based on the 1998 Washington Conference Principles on Nazi-Confiscated Art. -

Unitary, Federalized, Or Decentralized?: P-ISSN: 2655-2353, E-ISSN: 2655-6545 the Case Study of Daerah Istimewa

Article Info: Received : 02 – 07 – 2019 http://dx.doi.org/10.18196/iclr.1210 Revised : 02 – 08 – 2019 Accepted : 20 – 08 – 2019 Volume 1 No 2, June 2019 Unitary, Federalized, or Decentralized?: P-ISSN: 2655-2353, E-ISSN: 2655-6545 The Case Study of Daerah Istimewa Yogyakarta as The Special Autonomous Regions in Indonesia Ming-Hsi Sung 1, Hary Abdul Hakim2 1, 2 Department of Financial and Economic Law, Asia University, Taiwan E-mail: [email protected] 2 [email protected] 1Assistant Professor & Director, East Asia Law Center, Department of Financial and Economic Law, Asia University, Taiwan P 2Research Assistant, PAIR Labs; Assistant Research Fellow, East Asia Law Center, Department of Financial and Economic Law, Asia University, Taiwan Abstract granting autonomy to Daerah Istimewa Yogyakarta as a case study to The professed constitutional unitary argue for the latter, asserting that the case merely exemplifies the state claim has been highly debated. decentralization characteristic embedded in the Constitution. This paper Some argue that Indonesia shall be a first examines the political features of federalism through a historical unitary state in name, pursuant to legal perspective, showing that the current state system in Indonesia is Article 1 Para. III of the Indonesian decentralized but not federalized. This paper concludes that the Constitution, but Constitutional recognition of Daerah Istimewa Yogyakarta as an autonomous region is reforms after 1998 when the autocratic simply a practice of constitutional decentralization. This paper also President Gen. Soeharto stepped down higlights that with recent political development, echoing that the granted broad authority to local decentralization theory is not a product of legal interpretation, but a government, leading Indonesia to a constitutional and political reality. -

American Model United Nations Commission of Inquiry of 1948

American Model United Nations Commission of Inquiry of 1948 1 Final Report on the Situation in Indonesia, 27 May 1948 2 Overview 3 The Commission sought testimony from the Republic of Indonesia, the Kingdom of the Netherlands, Premier 4 Malewa of the State of East Indonesia, and the Indonesian Consular Commission to discuss the allegations made 5 by all parties and discern negotiable terms. The body recorded all notable events that transpired over time, and it 6 oversaw the negotiations between the Republican and Dutch parties. 7 Witness Testimonies 8 The Commission heard the representative of the Republic of Indonesia on 23 January 1948. Speaking in 9 favor of adhering to the Renville Agreement, he initially expressed outrage at Dutch violations thereof, including 10 drawing the Van Mook Line generously in the Netherlands' favor and not aligning with Dutch-occupied territory in 11 reality; establishing semi-autonomous states with administrations favoring Dutch colonial rule; using the Agreement 12 as a front to prepare for potential offenses similar to those on 11 November 1947; and maintaining the blockade 13 on the Republic's territory, thereby depriving Indonesia of civilian assistance and economic aid. Nevertheless, the 14 representative assured the Commission that the Republic was still fully committed both to adhering to the Linggadjati 15 and Renville Agreements and to negotiating with the Dutch for a mutually-satisfactory resolution to the conflict. The 16 representative rebuffed claims that the Republic was supporting guerrilla forces operating in Dutch territory behind 17 the Line, stating that any guerrilla forces represented the widely popular opposition to Dutch colonial presence. -

History of Banking in Indonesia: a Review

JOURNAL OF CRITICAL REVIEWS ISSN- 2394-5125 VOL 7, ISSUE 08, 2020 History of Banking in Indonesia: A Review Isnaini1, Ari Purwadi2, Reza Ronaldo3, Gusmaizal 4, AA Hubur5 1Universitas Medan Area, Medan, Indonesia. 2Universitas Wijaya Kusuma Surabaya, Indonesia. 3STEBI Lampung, Indonesia. 4Universitas Muhammadiyah Sumatera Barat, Indonesia 5Islamic Economics and Finance (IEF), Faculty of Business and Economics, Trisakti University, Indonesia. E-mail: [email protected], [email protected], [email protected] Received: 11.03.2020 Revised: 12.04.2020 Accepted: 28.05.2020 ABSTRACT: The history of banking in Indonesia can be answered in the following periods: 1) Period of Dutch colonial until Japanese occupation era (1827 - 8 March 1942). 2) Period of Japanese occupation until the Proclamation of Independence (8 March 1942 - 17 August 1945). 3) The Independence Period until the New Order year (Proclamation of 17 August 1945 until the issuance of the Banking Act of 1967/ 31 December 1967. 4) Period of banking after 31 December 1967. The Dutch colonial era in Indonesia arguably began in 1602, the establishment of VOC (Verenigde Oost Indische Companij). From the 19th century to 1942 (during the Japanese occupation), banks in Indonesia could be classified as follows: Netherlands-owned banks, England- owned banks, Chinese-owned banks, Japanese-owned banks and Native-owned banks. KEYWORDS: banking, monetary, Indonesia, government, central bank I. INTRODUCTION The Dutch East Indies government experienced various monetary difficulties as a legacy from the "Raffles administration" which ruled Indonesia for several years (1811-1816). The money circulating at that time was issued by the government. On 11 October 1827, De Javasche Bank was founded with first capital of one million guilders. -

Pidato - Sukarno ("Trikora") - Speech

Pidato - Sukarno ("Trikora") - Speech THE PEOPLE'S C0MMAND FOR THE LIBERATION OF WEST IRIAN Given by the President/Supreme Commander of the Armed Forces of the Republic of Indonesia. Commander-in-Chief of the Supreme Command for the Liberation of West Irian at a mass meeting in Jogjakarta, on 19th December 1961. DEPARTMENT OF INFORMATION REPUBLIC OF INDONESIA SPECIAL ISSUE, No.82 THE PEOPLE'S COMMAND, GIVEN BY THE PRESIDENT/SUPREME COMMANDER OF THE ARMED FORCES OF THE REPUBLIC OF INDONESIA, COMMANDER IN CHIEF OF THE SUPREME COMMAND FOR THE LIBERATION OF WEST IRIAN AT A MASS MEETING IN JOGJAKARTA, ON 19th DECEMBER 1961. Friends As was said by the Sultan just now, today, it is exactly 15 years since the day on which the city of Jogjakarta - or to be more exact, the Republic of Indonesia was attacked by the Dutch. Thirteen years ago there began what we call the second military action taken by the Dutch against the Republic of Indonesia. As all of you know, the military action which was begun here 13 years ago was the second, which means that we also underwent a first military action. And that first military action started on 21st July, 1947. But if it is viewed as a whole, seen as one historical event, then in fact we did not suffer, merely two military actions from the Dutch, the first on 21st July 1947, the second on 19th December 1948, No. In reality the Dutch, Dutch imperialism, on hundreds of occasions has taken military action against the Indonesian People. You know that the Dutch began to come here to Indonesia in 1596, when Admiral Cornelis De Houtman dropped anchor in Banten Bay. -

The Impact of Migration on the People of Papua, Indonesia

The impact of migration on the people of Papua, Indonesia A historical demographic analysis Stuart Upton Department of History and Philosophy University of New South Wales January 2009 A thesis submitted to the Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences in fulfilment of the requirements of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy 1 ‘I hereby declare that this submission is my own work and to the best of my knowledge it contains no materials previously published or written by another person, or substantial proportions of material which have been accepted for the award of any other degree or diploma at UNSW or any other educational institution, except where due acknowledgement is made in the thesis. Any contribution made to the research by others, with whom I have worked at UNSW or elsewhere, is explicitly acknowledged in the thesis. I also declare that the intellectual content of this thesis is the product of my own work, except to the extent that assistance from others in the project’s design and conception or in style, presentation and linguistic expression is acknowledged.’ Signed ………………………………………………. Stuart Upton 2 Acknowledgements I have received a great deal of assistance in this project from my supervisor, Associate-Professor Jean Gelman Taylor, who has been very forgiving of my many failings as a student. I very much appreciate all the detailed, rigorous academic attention she has provided to enable this thesis to be completed. I would also like to thank my second supervisor, Professor David Reeve, who inspired me to start this project, for his wealth of humour and encouragement.