GENERAL MEETING ~SSEMBLY Friday, 26 November 1954, at 3 P.M

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sultan Zainal Abidin Syah: from the Kingdomcontents of Tidore to the Republic of Indonesia Foreword

TAWARIKH:TAWARIKH: Journal Journal of Historicalof Historical Studies Studies,, VolumeVolume 12(1), 11(2), October April 2020 2020 Volume 11(2), April 2020 p-ISSN 2085-0980, e-ISSN 2685-2284 ABDUL HARIS FATGEHIPON & SATRIONO PRIYO UTOMO Sultan Zainal Abidin Syah: From the KingdomContents of Tidore to the Republic of Indonesia Foreword. [ii] JOHANABSTRACT: WAHYUDI This paper& M. DIEN– using MAJID, the qualitative approach, historical method, and literature review The– discussesHajj in Indonesia Zainal Abidin and Brunei Syah as Darussalam the first Governor in XIX of – WestXX AD: Irian and, at the same time, as Sultan of A ComparisonTidore in North Study Maluku,. [91-102] Indonesia. The results of this study indicate that the political process of the West Irian struggle will not have an important influence in the Indonesian revolution without the MOHAMMADfirmness of the IMAM Tidore FARISI Sultanate, & ARY namely PURWANTININGSIH Sultan Zainal Abidin, Syah. The assertion given by Sultan TheZainal September Abidin 30 Syahth Movement in rejecting and the Aftermath results of in the Indonesian KMB (Konferensi Collective Meja Memory Bundar or Round Table andConference) Revolution: in A 1949, Lesson because for the the Nation KMB. [103-128]sought to separate West Irian from Indonesian territory. The appointment of Zainal Abidin Syah as Sultan took place in Denpasar, Bali, in 1946, and his MARYcoronation O. ESERE, was carried out a year later in January 1947 in Soa Sio, Tidore. Zainal Abidin Syah was Historicalas the first Overview Governor of ofGuidance West Irian, and which Counselling was installed Practices on 23 inrd NigeriaSeptember. [129-142] 1956. Ali Sastroamidjojo’s Cabinet formed the Province of West Irian, whose capital was located in Soa Sio. -

The Indonesian Struggle for Independence 1945 – 1949

The Indonesian struggle for Independence 1945 – 1949 Excessive violence examined University of Amsterdam Bastiaan van den Akker Student number: 11305061 MA Holocaust and Genocide Studies Date: 28-01-2021 Supervisor: Prof. Dr. Ugur Ümit Üngör Second Reader: Dr. Hinke Piersma Abstract The pursuit of a free Indonesian state was already present during Dutch rule. The Japanese occupation and subsequent years ensured that this pursuit could become a reality. This thesis examines the last 4 years of the Indonesian struggle for independence between 1945 and 1949. Excessive violence prevailed during these years, both the Indonesians and the Dutch refused to relinquish hegemony on the archipelago resulting in around 160,000 casualties. The Dutch tried to forget the war of Indonesian Independence in the following years. However, whistleblowers went public in the 1960’s, resulting in further examination into the excessive violence. Eventually, the Netherlands seems to have come to terms with its own past since the first formal apologies by a Dutch representative have been made in 2005. King Willem-Alexander made a formal apology on behalf of the Crown in 2020. However, high- school education is still lacking in educating students on these sensitive topics. This thesis also discusses the postwar years and the public debate on excessive violence committed by both sides. The goal of this thesis is to inform the public of the excessive violence committed by Dutch and Indonesian soldiers during the Indonesian struggle for Independence. 1 Index Introduction -

Rijksuniversiteit Groningen

Decolonization and the Military: the Case of the Netherlands A Study in Political Reaction Rob Kroes, University of Amsterdam I Introduction *) When taken together, title and subtitle of this paper may seem to suggest, but certainly are not meant to implicate, that only m ilitary circles are apt to engage in right-wing political activism. On the contrary, this paper tries to indicate what specific groups within the armed forces of the Netherlands had an interest in opposing Indonesian independence, and what strategic alliances they engaged in with right- w in g c ivilian circles. In that sense, the subject of the paper is rather “underground” civil-military relations, as they exist alongside the level of institutionalized civil- m ilitary relations. Our analysis starts from a systematic theoretical perspective which, on the one hand, is intended to specify our expectations as to what interest groups within and without the m ilitary tended to align in opposing Indonesian independence and, on the other hand, to broadly characterize the options open to such coalitions for influencing the course of events either in the Netherlands or in the Dutch East Indies. II The theoretical perspective In two separate papers2) a process model of conflict and radicalism has been developed and further specified to serve as a basis for the study of m ilitary intervention in domestic politics. The model, although social-psychological in its emphasis on the *) I want to express my gratitude to the following persons who have been willing to respond to my request to discuss the role of the military during the Indonesian crisis: Messrs. -

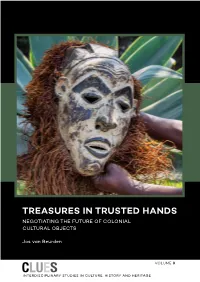

Treasures in Trusted Hands

Van Beurden Van TREASURES IN TRUSTED HANDS This pioneering study charts the one-way traffic of cultural “A monumental work of and historical objects during five centuries of European high quality.” colonialism. It presents abundant examples of disappeared Dr. Guido Gryseels colonial objects and systematises these into war booty, (Director-General of the Royal confiscations by missionaries and contestable acquisitions Museum for Central Africa in by private persons and other categories. Former colonies Tervuren) consider this as a historical injustice that has not been undone. Former colonial powers have kept most of the objects in their custody. In the 1970s the Netherlands and Belgium “This is a very com- HANDS TRUSTED IN TREASURES returned objects to their former colonies Indonesia and mendable treatise which DR Congo; but their number was considerably smaller than has painstakingly and what had been asked for. Nigeria’s requests for the return of with detachment ex- plored the emotive issue some Benin objects, confiscated by British soldiers in 1897, of the return of cultural are rejected. objects removed in colo- nial times to the me- As there is no consensus on how to deal with colonial objects, tropolis. He has looked disputes about other categories of contestable objects are at the issues from every analysed. For Nazi-looted art-works, the 1998 Washington continent with clarity Conference Principles have been widely accepted. Although and perspicuity.” non-binding, they promote fair and just solutions and help people to reclaim art works that they lost involuntarily. Prof. Folarin Shyllon (University of Ibadan) To promote solutions for colonial objects, Principles for Dealing with Colonial Cultural and Historical Objects are presented, based on the 1998 Washington Conference Principles on Nazi-Confiscated Art. -

American Model United Nations Commission of Inquiry of 1948

American Model United Nations Commission of Inquiry of 1948 1 Final Report on the Situation in Indonesia, 27 May 1948 2 Overview 3 The Commission sought testimony from the Republic of Indonesia, the Kingdom of the Netherlands, Premier 4 Malewa of the State of East Indonesia, and the Indonesian Consular Commission to discuss the allegations made 5 by all parties and discern negotiable terms. The body recorded all notable events that transpired over time, and it 6 oversaw the negotiations between the Republican and Dutch parties. 7 Witness Testimonies 8 The Commission heard the representative of the Republic of Indonesia on 23 January 1948. Speaking in 9 favor of adhering to the Renville Agreement, he initially expressed outrage at Dutch violations thereof, including 10 drawing the Van Mook Line generously in the Netherlands' favor and not aligning with Dutch-occupied territory in 11 reality; establishing semi-autonomous states with administrations favoring Dutch colonial rule; using the Agreement 12 as a front to prepare for potential offenses similar to those on 11 November 1947; and maintaining the blockade 13 on the Republic's territory, thereby depriving Indonesia of civilian assistance and economic aid. Nevertheless, the 14 representative assured the Commission that the Republic was still fully committed both to adhering to the Linggadjati 15 and Renville Agreements and to negotiating with the Dutch for a mutually-satisfactory resolution to the conflict. The 16 representative rebuffed claims that the Republic was supporting guerrilla forces operating in Dutch territory behind 17 the Line, stating that any guerrilla forces represented the widely popular opposition to Dutch colonial presence. -

The Impact of Migration on the People of Papua, Indonesia

The impact of migration on the people of Papua, Indonesia A historical demographic analysis Stuart Upton Department of History and Philosophy University of New South Wales January 2009 A thesis submitted to the Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences in fulfilment of the requirements of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy 1 ‘I hereby declare that this submission is my own work and to the best of my knowledge it contains no materials previously published or written by another person, or substantial proportions of material which have been accepted for the award of any other degree or diploma at UNSW or any other educational institution, except where due acknowledgement is made in the thesis. Any contribution made to the research by others, with whom I have worked at UNSW or elsewhere, is explicitly acknowledged in the thesis. I also declare that the intellectual content of this thesis is the product of my own work, except to the extent that assistance from others in the project’s design and conception or in style, presentation and linguistic expression is acknowledged.’ Signed ………………………………………………. Stuart Upton 2 Acknowledgements I have received a great deal of assistance in this project from my supervisor, Associate-Professor Jean Gelman Taylor, who has been very forgiving of my many failings as a student. I very much appreciate all the detailed, rigorous academic attention she has provided to enable this thesis to be completed. I would also like to thank my second supervisor, Professor David Reeve, who inspired me to start this project, for his wealth of humour and encouragement. -

Jihadists Assemble: the Rise of Militant Islamism in Southeast Asia

JIHADISTS ASSEMBLE: THE RISE OF MILITANT ISLAMISM IN SOUTHEAST ASIA Quinton Temby A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy of the Australian National University Department of Political & Social Change Coral Bell School of Asia Pacific Affairs College of Asia & the Pacific Australian National University © Copyright Quinton Temby All Rights Reserved July 2017 I certify that this dissertation is my own original work. To the best of my knowledge, it contains no material that has been accepted for the award of a degree or diploma in any university and contains no material previously published by another person, except where due reference is made in the text of the dissertation. Quinton Temby ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The preparation of this thesis has left me indebted to many people. It would not have been possible at all without the generous support of my primary supervisor, Associate Professor Greg Fealy, who encouraged my curiosity for this topic from the outset and who expertly guided and challenged me throughout the long process of research and writing. On my supervisory panel, I was privileged to have Professor Ed Aspinall and Professor Robert Cribb, whose critical feedback and scholarly example has been an object lesson. For help and guidance in ways impossible to count or measure, much less repay, I am grateful to Sidney Jones. In both Canberra and Jakarta, I enjoyed the support of Associate Professor Marcus Mietzner. For persistently challenging me to think regionally, I owe much of the vision of this thesis to Dr Kit Collier. In Indonesia, above all I would like to thank Sita W. -

The Political Events in the Repuhlic of Lndonesia

The Political Events in the Repuhlic of lndonesia • Pnbllihed by TUE NETUERLANDS INFORMATlON BUREAU 10 ROCKEFELLER PLAZA NEW YORK CITY < DI.tttbuted b:r the Netherltuuü lnfor.maUon B~ ... 10 Boek.,ellel' p ...... New Yqrk• .N. Y •• _bIeb lt NClM«ed wUh tb. JroPt'lJ'u A ..ent. ...atJ&atlon 8eoUoDo- ~ent ot "Jutlee, WaablapOIl. 1;). C., .... -.eD" ot tiro. Bq).. l Nethel'- land. aoYennnent. A coPJ' ot til'- materIal I. betn. 6led ..Ith the Depart.meoi al iJ ..... w~ the ~on .t.... ent of ihe NetberlanclJl .JDfol'lltAUcm Dure,t:U I. aTaIlable fOf' blatMctJoll. 'Ee1'l4Ihtlotl under the Jterelp qf'a,Q ~a1 ... _don Ad doe. Doi buUeate appl'Ovai or ar.pproYal of thb maUrlai hJ' 'he UnJted. 8tate. GoUftlDlen\' The Political Events in the Republic of Indonesia A Review of the Developments in the Illcloneûan Repltblic (Java aml Sumatra) since the Japa Tlese slurender. Togcther with Statements hy the Netherlands and Netherlands Indies Governments, and Complete Text of the Linggadjati Agreement. J r Contents PART I Chapter I. General Charaeter of the Republic........................... .. .5 Chapter 2. Netherlands Poliey in Indonesia ......... 8 Chapter 3. The N egotiations ....................................................................................... 11 Chapter 4. Review of Negotiations from May 27 to July 20, 1947 13 Chapter 5. Propaganda in the Rep ublic. .................................... 17 Chapter 6. The Republic aud th e Truc<-...................................... 21 Chapter 7. Republican Activities against East Indoncsia and Bo rn co ..... _.... _........ ___ .. __ ... __ ........ __ ..... _.... _.. _.. ....... 23 Chapter 8. The Republic aud the Food Supply.................... 27 Chapter 9. Two Months after the Military Action ........ .. 30 PART IJ I. -

4 Building the Islamic State from Ideal to Reality (1947-1949)

4 Building the Islamic state From ideal to reality (1947-1949) After much preparation, during the 20th gathering of the Dewan Ima- mah in Cimampang, with the attendance of Kartosuwiryo, K.H. Gozali Toesi, Sanoesi Partawidjaja, Raden Oni, and Toha Arsjad, on 7 August 1949 the Negara Islam Indonesia is officially proclaimed with the words: Proclamation of the Establishment of the Islamic State of Indonesia [NII], Dengan Nama Allah, Jang Maha Esa dan Jang Maha Asih, we, the Islamic Community of the Indonesian Nation announce the establishment of the Negara Islam Indonesia. And the law that governs the NII is Islamic Law.1 The 1947 invasion of West Java pushed Masyumi to proclaim resis- tance against the Dutch a jihad obligatory for all Muslims. Following the discord over the Linggadjati Agreement Sjahrir was forced to resign, then Masyumi refused to join Sjarifuddin’s ‘socialist’ cabinet, and by late September tensions could no longer be confined to the political field, as they spilled out among the population and onto the battlefield. The violence that had dotted West Java throughout 1946- 47 further escalated, even as the Indonesian Republic in Yogyakarta and the Dutch embarked on another round of diplomatic talks. The Renville Agreement, signed by Van Mook and Sjarifuddin on 17 January 1948, was the outcome of heavy pressure from the United States and the United Nations. The international commu- nity had been lobbying to find a diplomatic end to the impasse caused by the military invasion on Java and Sumatra and to estab- lish a roadmap for Indonesia’s self-government. -

The Position of the Federal Consultative Assembly – ‘Bijeenkomst Voor Federaal Overleg’ (BFO) – During the Dutch-Indonesian Conflict, 1945-1950

Caught between the Netherlands and the Republic: the position of the Federal Consultative Assembly – ‘Bijeenkomst voor Federaal Overleg’ (BFO) – during the Dutch-Indonesian conflict, 1945-1950. Author: Ruben Barink SID: 1348817 Supervisor: Roel Frakking Date: 25-05-2020 1 Acknowledgements The thesis before you could not have been made possible without the help of others. I am very grateful to my instructor Roel Frakking for his instructions, feedback and patience. Also, I would like to thank Maartje Janse for her initial feedback and functioning as second reader. 2 Table of contents Acknowledgements ................................................................................................................................. 2 Introduction ............................................................................................................................................. 5 Reasons for their virtual absence from the literary debate ................................................................ 6 Filling a complex gap ........................................................................................................................... 8 Research-question and theory .......................................................................................................... 11 Methodology ..................................................................................................................................... 15 Chapters division .............................................................................................................................. -

ENERAL Lssembly

United Nations fiRST COMMITTEE, /31st ;ENERAL MEETING Saturday, 27 November 1954, lSSEMBLY at 10.30 a.m. VINTH SESSION Official Records New York CONTENTS the Netherlands East Indies should become an inde Page pendent State as soon as possible'? ~enda item 61: 5. A commission had been set up by the first Round The question of \Vest Irian (West New Guinea) (con- Table Conference to inquire into the situation in New tinued) . 421 Guinea, but difficulties had arisen at the second con ference held at The Hague, and it had been to meet those difficulties that article 2 of the Charter of trans Chairman: Mr. Francisco URRUTIA (Colembia). fer of sovereignty (Sj1417/Add.1), relating to West Irian, had been drafted. While, as the representative of Liberia had said (729th meeting), the interpreta tion given by the Australian representative (727th AGENDA ITEM 61 meeting) was possibly not without some foundation, it was pointless to make the subtle distinction which lie question of West Irian (West New Guinea) the representative of Australia had made between a (A/2694, A/C.l/L.l09) (continued) complete transfer of sovereignty and a transfer of sovereignty over the whole territory. The wording of Mr. TRUJILLO (Ecuador) recalled that one dele article 1 of the Charter of transfer was perfectly tion had expressed the fear that the present discus clear, and it would therefore only complicate matters m would cause dissension. However, if only minor to resort to an interpretation of the spirit of that word oblems which, unlike the one which the Committee ing. -

ASEAN Ebcid:Com.Britannica.Oec2.Identifier.Articleidentifier?Tocid=9068910&Ar

ASEAN ebcid:com.britannica.oec2.identifier.ArticleIdentifier?tocId=9068910&ar... ASEAN Encyclopædia Britannica Article in full Association of Southeast Asian Nations international organization established by the governments of Indonesia, Malaysia, the Philippines, Singapore, and Thailand in 1967 to accelerate economic growth, social progress, and cultural development and to promote peace and security in Southeast Asia. Brunei joined in 1984, followed by Vietnam in 1995, Laos and Myanmar in 1997, and Cambodia in 1999. The ASEAN region has a population of approximately 500 million and covers a total area of 1.7 million square miles (4.5 million square km). ASEAN replaced the Association of South East Asia (ASA), which had been formed by the Philippines, Thailand, and the Federation of Malaya (now part of Malaysia) in 1961. Under the banner of cooperative peace and shared prosperity, ASEAN's chief projects centre on economic cooperation, the promotion of trade among ASEAN countries and between ASEAN members and the rest of the world, and programs for joint research and technical cooperation among member governments. Held together somewhat tenuously in its early years, ASEAN achieved a new cohesion in the mid-1970s following the changed balance of power in Southeast Asia after the end of the Vietnam War. The region's dynamic economic growth during the 1970s strengthened the organization, enabling ASEAN to adopt a unified response to Vietnam's invasion of Cambodia in 1979. ASEAN's first summit meeting, held in Bali, Indonesia, in 1976, resulted in an agreement on several industrial projects and the signing of a Treaty of Amity and Cooperation and a Declaration of Concord.