Culture and Privilege in Capitalist Asia

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

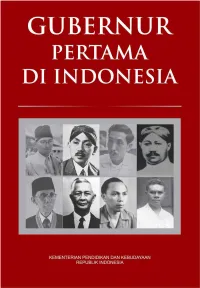

Teuku Mohammad Hasan (Sumatra), Soetardjo Kartohadikoesoemo (Jawa Barat), R

GUBERNUR PERTAMA DI INDONESIA GUBERNUR PERTAMA DI INDONESIA KEMENTERIAN PENDIDIKAN DAN KEBUDAYAAN REPUBLIK INDONESIA GUBERNUR PERTAMA DI INDONESIA PENGARAH Hilmar Farid (Direktur Jenderal Kebudayaan) Triana Wulandari (Direktur Sejarah) NARASUMBER Suharja, Mohammad Iskandar, Mirwan Andan EDITOR Mukhlis PaEni, Kasijanto Sastrodinomo PEMBACA UTAMA Anhar Gonggong, Susanto Zuhdi, Triana Wulandari PENULIS Andi Lili Evita, Helen, Hendi Johari, I Gusti Agung Ayu Ratih Linda Sunarti, Martin Sitompul, Raisa Kamila, Taufik Ahmad SEKRETARIAT DAN PRODUKSI Tirmizi, Isak Purba, Bariyo, Haryanto Maemunah, Dwi Artiningsih Budi Harjo Sayoga, Esti Warastika, Martina Safitry, Dirga Fawakih TATA LETAK DAN GRAFIS Rawan Kurniawan, M Abduh Husain PENERBIT: Direktorat Sejarah Direktorat Jenderal Kebudayaan Kementerian Pendidikan dan Kebudayaan Jalan Jenderal Sudirman, Senayan Jakarta 10270 Tlp/Fax: 021-572504 2017 ISBN: 978-602-1289-72-3 SAMBUTAN Direktur Sejarah Dalam sejarah perjalanan bangsa, Indonesia telah melahirkan banyak tokoh yang kiprah dan pemikirannya tetap hidup, menginspirasi dan relevan hingga kini. Mereka adalah para tokoh yang dengan gigih berjuang menegakkan kedaulatan bangsa. Kisah perjuangan mereka penting untuk dicatat dan diabadikan sebagai bahan inspirasi generasi bangsa kini, dan akan datang, agar generasi bangsa yang tumbuh kelak tidak hanya cerdas, tetapi juga berkarakter. Oleh karena itu, dalam upaya mengabadikan nilai-nilai inspiratif para tokoh pahlawan tersebut Direktorat Sejarah, Direktorat Jenderal Kebudayaan, Kementerian Pendidikan dan Kebudayaan menyelenggarakan kegiatan penulisan sejarah pahlawan nasional. Kisah pahlawan nasional secara umum telah banyak ditulis. Namun penulisan kisah pahlawan nasional kali ini akan menekankan peranan tokoh gubernur pertama Republik Indonesia yang menjabat pasca proklamasi kemerdekaan Indonesia. Para tokoh tersebut adalah Teuku Mohammad Hasan (Sumatra), Soetardjo Kartohadikoesoemo (Jawa Barat), R. Pandji Soeroso (Jawa Tengah), R. -

The May 1998 Riots and the Emergence of Chinese Indonesians: Social Movements in the Post-Soeharto Era*

The May 1998 Riots and the Emergence of Chinese Indonesians: Social Movements in the Post-Soeharto Era* Johanes Herlijanto Lecturer, Department of History, Faculty of Humanities, University of Indonesia I. Introduction The social movements launched by Chinese-Indonesians to struggle for recognition of their ethnic identity in post-Soeharto Indonesia should not be understood merely as a result of the collapse of the New Order authoritarian regime. On the contrary, the eagerness of Chinese Indonesians to participate in such movements should also be perceived as a changing process of their perception of their position in Indonesian society. This change in perception is most importantly related to a strategy of seeking security in a society where the ethnic Chinese often become the target of discrimination, violence and riots. This paper argues that the May 1998 riots have had an important influence on changing process of perception among Chinese Indonesians. It is after this incident that the perception which encouraged Chinese-Indonesians to struggle for the recognition of their ethnic identity as well as for the abolishment of all discrimination against them began to emerge and develop. One way to understand this is by posing questions of how the Chinese-Indonesians perceived the May 1998 tragedy and how have they constructed an alternative understanding about their position in Indonesian society. These questions will be the main focus of this paper. In dealing with these questions, this paper will discuss three important * Revised version of the paper presented at the 18th Conference of International Association of Historians of Asia (IAHA), December 6-10, 2004, Academia Sinica, Taipei, Taiwan. -

The Role of Ethnic Chinese Minority in Developntent: the Indonesian Case

Southeast Asian Studies. Vol. 25, No.3, December 1987 The Role of Ethnic Chinese Minority in Developntent: The Indonesian Case Mely G. TAN* As recent writIngs indicate, the term Introduction more commonly used today is "ethnic Chinese" to refer to the group as a Despite the manifest diversity of the whole, regardless of citizenship, cultural ethnic Chinese in Southeast Asia, there orientation and social identification.2) is still the tendency among scholars The term ethnic or ethnicity, refers to focusing on this group, to treat them a socio-cultural entity. In the case of as a monolithic entity, by referring to the ethnic Chinese, it refers to a group all of them as "Chinese" or "Overseas with cultural elements recognizable as Chinese." Within the countries them or attributable to Chinese, while socially, selves, as In Indonesia, for instance, members of this group identify and are this tendency is apparent among the identified by others as constituting a majority population in the use of the distinct group. terms "orang Cina," "orang Tionghoa" The above definition IS III line with or even "hoakiau."D It is our conten the use in recent writings on this topic. tion that these terms should only be In the last ten years or so, we note a applied to those who are alien, not of revival of interest In ethnicity and mixed ancestry, and who initially do ethnic groups, due to the realization not plan to stay permanently. We also that the newly-developed as well as the submit that, what terminology and what established countries In Europe and definition is used for this group, has North America are heterogeneous socie important implications culturally, so ties with problems In the relations cially, psychologically and especially for policy considerations. -

How Does the Introduction of the Idea of Civil Society and the Development

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by RMIT Research Repository TERROR IN INDONESIA: TERRORISM AND THE REPRESENTATION OF RECENT TERRORIST ATTACKS IN THREE INDONESIAN NEWS PUBLICATIONS WITHIN A CONTEXT OF CULTURAL AND SOCIAL TRANSITION PRAYUDI AHMAD A dissertation submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy at RMIT University SCHOOL OF MEDIA AND COMMUNICATION COLLEGE OF DESIGN AND SOCIAL CONTEXT ROYAL MELBOURNE INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY MELBOURNE, AUSTRALIA JUNE 2010 ii DECLARATION I certify that this dissertation does not incorporate without acknowledgement any material which has been submitted for an award of any other university or other institutions. To the best of my knowledge and belief, it contains no material previously published or written by another person, except where due reference is made in the text of the dissertation. The content of the dissertation is the result of work which has been carried out since the official commencement date of the approved research program. Any editorial work, paid or unpaid, carried out by a third party is acknowledged. Signed : Date : June 2010 iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This dissertation is the outcome of four years of doctoral research in the School of Media and Communication, College of Design and Social Context, RMIT University, Melbourne, Australia. During this time, I have worked with a great number of people who have contributed in various ways to the research and the completion of the dissertation. It is a pleasure to convey my gratitude to them all and convey my humble acknowledgment. First and foremost I offer my sincerest gratitude to my supervisors, Professor Dr. -

RIVALITAS ELIT BANGSAWAN DENGAN KELOMPOK TERDIDIK PADA MASA REVOLUSI: Analisis Terhadap Pergulatan Nasionalisme Lokal Di Sulawesi Selatan Menuju NKRI

SEMINAR NASIONAL “Pendidikan Ilmu-Ilmu Sosial Membentuk Karakter Bangsa Dalam Rangka Daya Saing Global” Kerjasama: Fakultas Ilmu Sosial Universitas Negeri Makassar dan Himpunan Sarjana Pendidikan Ilmu-ilmu Sosial Indonesia Grand Clarion Hotel, Makassar, 29 Oktober 2016 RIVALITAS ELIT BANGSAWAN DENGAN KELOMPOK TERDIDIK PADA MASA REVOLUSI: Analisis Terhadap Pergulatan Nasionalisme Lokal di Sulawesi Selatan menuju NKRI Najamuddin Fakultas Ilmu Sosial, Universitas Negeri Makassar ABSTRAK Stratifikasi sosial masyarakat Bugis-Makassar telah memberikan posisi istimewa terhadap kaum bangsawan sebagai elit strategis dari kelompok masyarakat lainnya dalam struktur sosial, dan sebagai pemimpin puncak dalam struktur politik atau struktur kekuasaan. Sementara elit terdidik muncul sebagai elit kedua dalam struktur sosial nasyarakat yang turut berpengaruh dalam dinamika politik lokal di masa revolusi. Ketika kelompok terdidik tampil dalam Pergerakan Nasional di Sulawesi Selatan bersama elit bangsawan, politik kolonial Belanda berhasil mempolarisasi keduanya menjadi bagian yang terpisah menjadi konflik di awal kemerdekaan RI. Kedua kelompok elit tersebut kemudian memilih jalannya masing masing dalam proses perjuangan. Konflik tersebut akhirnya banyak berpengaruh terhadap kelanjutan revolusi di Sulawesi Selatan dan sepanjang berdirinya Negara Indonesia Timur (NIT) hingga menyatakan diri bergabung dengan RI dalan negara kesatuan. Kata kunci: Rivalitas Elit, Bangsawan, Kelompok Terdidik PENDAHULUAN Persiapan menjelang kemerdekaan RI di Sulawesi Selatan -

The State and Illegality in Indonesia in Illegality and State the the STATE and ILLEGALITY in INDONESIA

Edited by Edward Aspinall and Gerry van Klinken The state and illegality in Indonesia THE STATE AND ILLEGALITY IN INDONESIA The popular 1998 reformasi movement that brought down President Suharto’s regime demanded an end to illegal practices by state offi cials, from human rights abuse to nepotistic investments. Yet today, such practices have proven more resistant to reform than people had hoped. Many have said corruption in Indonesia is “entrenched”. We argue it is precisely this entrenched character that requires attention. What is state illegality entrenched in and how does it become entrenched? This involves studying actual cases. Our observations led us to rethink fundamental ideas about the nature of the state in Indonesia, especially regarding its socially embedded character. We conclude that illegal practices by state offi cials are not just aberrations to the state, they are the state. Almost invariably, illegality occurs as part of collective, patterned, organized and collaborative acts, linked to the competition for political power and access to state resources. While obviously excluding many without connections, corrupt behaviour also plays integrative and stabilizing functions. Especially at the lower end of the social ladder, it gets a lot of things done and is often considered legitimate. This book may be read as a defence of area studies approaches. Without the insights that grew from applying our area studies skills, we would still be constrained by highly stylized notions of the state, which bear little resemblance to the state’s actual workings. The struggle against corruption is a long-term political process. Instead of trying to depoliticize it, we believe the key to progress is greater popular participation. -

Rewriting Indonesian History the Future in Indonesia’S Past

No. 113 Rewriting Indonesian History The Future in Indonesia’s Past Kwa Chong Guan Institute of Defence and Strategic Studies Singapore June 2006 With Compliments This Working Paper series presents papers in a preliminary form and serves to stimulate comment and discussion. The views expressed are entirely the author’s own and not that of the Institute of Defence and Strategic Studies The Institute of Defence and Strategic Studies (IDSS) was established in July 1996 as an autonomous research institute within the Nanyang Technological University. Its objectives are to: • Conduct research on security, strategic and international issues. • Provide general and graduate education in strategic studies, international relations, defence management and defence technology. • Promote joint and exchange programmes with similar regional and international institutions; and organise seminars/conferences on topics salient to the strategic and policy communities of the Asia-Pacific. Constituents of IDSS include the International Centre for Political Violence and Terrorism Research (ICPVTR), the Centre of Excellence for National Security (CENS) and the Asian Programme for Negotiation and Conflict Management (APNCM). Research Through its Working Paper Series, IDSS Commentaries and other publications, the Institute seeks to share its research findings with the strategic studies and defence policy communities. The Institute’s researchers are also encouraged to publish their writings in refereed journals. The focus of research is on issues relating to the security and stability of the Asia-Pacific region and their implications for Singapore and other countries in the region. The Institute has also established the S. Rajaratnam Professorship in Strategic Studies (named after Singapore’s first Foreign Minister), to bring distinguished scholars to participate in the work of the Institute. -

I I I I 1 I I I I I I I I I I I I

I I ±1 I I 1 I ENVIRONMENTAL HEALTH PROJECT I I I I I I I I I I Picpnrcd [u:. ENVIRONMENTAL HEALTH DIVISION I OFFICE OF HEALTH AND NUTRITION USAit) CLTltL: ~~il [‘J~)LJ~I[iL’!), ~ C!!i~~T~i~[;iL: 1 I GLJ~LJL; L: G)ui~:!P:uq::n~s,FILM SL:upn: rUiL) I ~ tu. U S AL MC~F Ii ‘L t I Liut Ici! u’ \ L I t ~ii f 202.2_936U_13031 I - - -- - - ---I I ENVIRONMENTAL HEALTH PROJECT WASH Reprint: Field Report No. 387 Survey of Pnvate-Sector Participation in Selected Cities in Indonesia J. Woodcock M. Maulana LIBRA~Y R. Thabrani INTERNATIONAL RFFERENCE CfrNT~Ø FOR COMMUNITY WATER SUPPLY ANØ SANITATlONd~ber1993 Co-Sponsored by USAI D/Indonesia Office of Private Enterprise Development, Urban Policy Division (PED/UPD) and the PURSE Steering Committee, composed of BAPPENAS, the Ministry of Home Affairs and -t~~~f Public Works LIBRARYc ~WA~skî~to~ 39g CENTRE FOR OOMMUNI 1 y WA UE~ ~-L’~ AND SAM ATflN ~C) 1 PC U-3’~ ~ 2U.~09AD T;~ 1(~(070) 81 1911 ext. 1411142 1f~J ~ Environmental Health Project Contract No. HRN-5994-C-0O-3036-00, Project No 936-5994 is sponsored by the Bureau for Global Programs, Field Support and Research Office of Health and Nutntion U.S. Agency for International Development Washington, DC 20523 WASH and EHP With the launching of the United Nations International Drinking Water Supply and Sanitation Decade in 1979, the United States Agency for International Development (USAI D) decided to augment and streamline its technical assistance capability in water and sanitation and, in 1980, funded the Water and Sanitation for Health Project (WASH). -

Daftar Arsip Statis Foto Kementerian Penerangan RI : Wilayah DKI Jakarta 1950 1 11 1950.08.15 Sidang BP

ISI INFORMASI ARSIP FOTO BIDANG POLITIK DAN PEMERINTAHAN KURUN KEGIATAN / NO. POSITIF/ NO ISI INFORMASI UKURAN FOTOGRAFER KETERANGAN WAKTU PERISTIWA NEGATIF 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 1 1950.08.15 Sidang Pertama Ketua DPR Sartono sedang membuka sidang pertama Dewan 50001 5R v. Eeden Dewan Perwakilan Perwakilan Rakyat, duduk di sebelahnya, Menteri Rakyat Penerangan M.A. Pellaupessy. 2 Presiden Soekarno menyampaikan pidato di depan Anggota 50003 5R v. Eeden DPR di Gedung Parlemen RIS. [Long Shot Suasana sidang gabungan antara Parlemen RI dan RIS di Jakarta. Dalam rapat tersebut Presiden Soekarno membacakan piagam terbentuknya NKRI dan disetujui oleh anggota sidang.] 3 Presiden Soekarno keluar dari Gedung DPR setelah 50005 5R v. Eeden menghadiri sidang pertama DPR. 4 Perdana Menteri Mohammad Natsir sedang bercakap-cakap 50006 5R v. Eeden dengan Menteri Dalam Negeri Mr. Assaat (berpeci) setelah sidang DPR di Gedung DPR. 5 Lima orang Anggota DPR sedang berunding bersama di 50007 5R v. Eeden sebuah ruangan di Gedung DPR, setelah sidang pertama DPR. 6 Ketua Sementara DPR Dr. Radjiman Wedyodiningrat sedang 50008 5R v. Eeden membuka sidang pertama DPR, di sebelah kanannya duduk Sekretaris. 7 Ketua Sementara DPR Dr. Radjiman Wedyodiningrat sedang 50009 5R v. Eeden membuka sidang pertama DPR, di sebelah kirinya duduk Ketua DPR Mr. Sartono. 8 Suasana ruangan pada saat sidang pertama DPR Negara 50010 5R v. Eeden Kesatuan. 9 [1950.08.15] Sidang BP. KNIP Suasana sidang Badan Pekerja Komite Nasional Indonesia 5R Moh. Irsjad 50021 Pusat (BP. KNIP) di Yogyakarta. 10 Presiden Soekarno sedang berpidato sidang BP. KNIP di 5R 50034 Yogyakarta. -

Proquest Dissertations

INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction Is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand comer and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. Photographs included in the original manuscript have been reproduced xerographically in this copy. Higher quality 6” x 9* black and white photographic prints are available for any photographs or illustrations appearing in this copy for an additional charge. Contact UMI directly to order. Bell & Howell Information and Learning 300 North Zeeb Road, Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 USA 800-521-0600 UMI LIBERALIZING NEW ORDER INDONESIA: IDEAS, EPISTEMIC CCMMÜNITY, AND ECONŒIC POLICY CHANGE, 1986-1992 DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Rizal Mallarangeng, MA. ***** The Ohio State University 2000 Dissertation Committee: proved by Professor R. -

Proklamasi Dan Dilema Republik Di Indonesia Timur

Seminar Nasional “Proklamasi Kemerdekaan RI di 8 Wilayah” PROKLAMASI DAN DILEMA REPUBLIK DI INDONESIA TIMUR Abd. Rahman Hamid Jurusan Sejarah Univ. Hasanuddin - Makassar Prolog O Proklamasi kemerdekaan 17-8-’45 PPKI menetapkan 8 propinsi (19-8-’45) O Perundingan Linggajati (Maret 1946) wilayah RI: Jawa, Madura, dan Sumatera O Proklamasi terbentuknya NKRI 17-8-’50 O Proklamasi sbg “tonggak” atau “terminal sejarah” Dinamika Lokal sebelum Proklamasi O Gerakan Merah Putih di Sulawesi (tengah) Februari 1942: Gorontalo, Toli-toli, Luwuk, dan Ampana (Poso) O Alih kuasa pemerintahan (sementara), dari Jepang kepada (di) Palu, Poso, Gorontalo. Tapi, tidak di Minahasa. O Sulawesi tenggara bendara merah putih dan lagu Indonesia Raya di distrik Gu (Buton) bersama bendera dan lagu Jepang. Menjelang Proklamasi O Akhir tahun 1944, Bung Karno, Mr. Ahmad Subardjo, dan Mr. Summanang (tiba) di Makassar untuk mempersiapkan kemerdekaan. Bendera merah putih dikibarkan. O Tetapi, kemudian diturunkan oleh Jepang Memberikan motivasi/harapan akan merdekaan O 1 Agustus ‘45, merah putih di Irian (kampung Harapan Jaya) oleh: Marcus Kasiepo, Frans Kasiepo, dll Proklamasi dan Tindak Lanjutnya OProklamasi 17-8-45 di Jakarta ORatulangi bersama Andi Pangerang Pettarani, Andi Sultan Dg. Raja, dan Andi Zainal Abidin ke Jakarta (10-8- ’45). OTerbentuk 8 propinsi, al. Sulawesi (Ratulangi) dan Maluku (Latuharhary). Mendukung Republik (Maluku) O Latuharhary sulit kembali, lalu membentuk pemerintahan di Jakarta (kmd Yogyakarta). Membuka kantor perwakilan di Jawa dan Sumatera membimbing sekitar 30.000 penduduk Maluku di sana. O Perserikatan Pemuda Ambon di Jawa berjuang “membela dan mempertahankan pemerintahan Republik” Semarak Kemerdekaan O Minahasa, merah putih dikibarkan 22 Agustus ‘45 O Pelaut Buton mengibarkan merah putih sepanjang route pelayaran (Sumatera-Jawa-Buton). -

BAB IV LAPORAN HASIL PENELITIAN A. Gambaran Singkat Lokasi Penelitian 1. Sejarah Fakultas Tarbiyah Dan Keguruan Keinginan Untuk

BAB IV LAPORAN HASIL PENELITIAN A. Gambaran Singkat Lokasi Penelitian 1. Sejarah Fakultas Tarbiyah Dan Keguruan Keinginan untuk mendirikan Fakultas Tarbiyah IAIN Antasari Banjarmasin pada dasarnya sudah lama direncanakan oleh tokoh-tokoh pendidikan di Banjarmasin, apalagi dengan semakin banyaknya alumnus dari lembaga pendidikan setingkat SMTA, baik yang berstatus negeri maupun yang swasta, yang ingin melanjutkan pendidikannya ke jenjang yang lebih tinggi atau perguruan tinggi. Di samping itu, kenyataan menunjukkan bahwa guru-guru agama yang berpendidikan tinggi masih sangat langka, baik di sekolah lanjutan pertama (SMP dan MTs) maupun di sekolah lanjutan atas (SMA dan Aliyah). Begitu pula dengan calon-calon dosen baik di IAIN Antasari sendiri maupun di perguruan tinggi umum lainnya dirasakan masih sangat kurang. Kenyataan tersebut ditambah lagi bahwa IAIN Antasari yang berpusat di kota Banjarmasin hanya mempunyai satu fakultas, yaitu Fakultas Syari’ah, sedang Fakultas Tarbiyah sendiri saat itu hanya ada di Barabai sebagai cabang dari IAIN Antasari di Banjarmasin, di samping Fakultas Ushuluddin yang berada di Amuntai. Berdasarkan kenyataan di atas, H. Zafry Zamzam sebagai Rektor IAIN Antasari pada waktu itu merasa perlu agar di Banjarmasin sendiri didirikan pula Fakultas Tarbiyah. Di samping fakultas tersebut dapat melengkapi kekurangan fakultas di IAIN Antasari Banjarmasin, juga diharapkan 50 51 mampu menyahuti berbagai aspirasi dari masyarakat kota Banjarmasin dan sekitarnya yang berkembang saat itu. Pada tanggal 22 September 1965, rektor IAIN Antasari mengeluarkan surat keputusan Nomor 14/BR/IV/1965 tentang pembukaan Fakultas Tarbiyah IAIN Antasari di Banjarmasin. Terbitnya SK Rektor tersebut, juga punya kaitan erat dengan adanya penyerahan Fakultas Publisistik UNISAN (Universitas Islam Kali-mantan) di Banjarmasin untuk dijadikan Fakultas Tarbiyah Banjarmasin.