The Politics of Protest Events

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Surrealist Painting in Yogyakarta Martinus Dwi Marianto University of Wollongong

University of Wollongong Research Online University of Wollongong Thesis Collection University of Wollongong Thesis Collections 1995 Surrealist painting in Yogyakarta Martinus Dwi Marianto University of Wollongong Recommended Citation Marianto, Martinus Dwi, Surrealist painting in Yogyakarta, Doctor of Philosophy thesis, Faculty of Creative Arts, University of Wollongong, 1995. http://ro.uow.edu.au/theses/1757 Research Online is the open access institutional repository for the University of Wollongong. For further information contact the UOW Library: [email protected] SURREALIST PAINTING IN YOGYAKARTA A thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the award of the degree DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY from UNIVERSITY OF WOLLONGONG by MARTINUS DWI MARIANTO B.F.A (STSRI 'ASRT, Yogyakarta) M.F.A. (Rhode Island School of Design, USA) FACULTY OF CREATIVE ARTS 1995 CERTIFICATION I certify that this work has not been submitted for a degree to any other university or institution and, to the best of my knowledge and belief, contains no material previously published or written by any other person, except where due reference has been made in the text. Martinus Dwi Marianto July 1995 ABSTRACT Surrealist painting flourished in Yogyakarta around the middle of the 1980s to early 1990s. It became popular amongst art students in Yogyakarta, and formed a significant style of painting which generally is characterised by the use of casual juxtapositions of disparate ideas and subjects resulting in absurd, startling, and sometimes disturbing images. In this thesis, Yogyakartan Surrealism is seen as the expression in painting of various social, cultural, and economic developments taking place rapidly and simultaneously in Yogyakarta's urban landscape. -

The Second African International Conference on Industrial Engineering and Operations Management

IEOM The Second African International Conference on Industrial Engineering and Operations Management December 7-10, 2020 Host: Harare, Zimbabwe University of Zimbabwe Industrial Engineering and Operations Management Society International 21415 Civic Center Dr., Suite 217, Southfield, Michigan 48076, USA IEOM Harare Conference December 7-10, 2020 Sponsors and Partners Organizer IEOM Society International Industrial Engineering and Operations Management Society International 21415 Civic Center Dr., Suite 217, Southfield, Michigan 48076, USA, p. 248-450-5660, e. [email protected] Welcome to the 2nd African IEOM Society Conference Harare, Zimbabwe To All Conference Attendees: We want to welcome you to the 2nd African IEOM Society Conference in Harare, Zimbabwe hosted by the University of Zimbabwe, December 7-10, 2020. This unique international conference provides a forum for academics, researchers, and practitioners from many industries to exchange ideas and share recent developments in the fields of industrial engineering and operations management. This diverse international event provides an opportunity to collaborate and advance the theory and practice of significant trends in industrial engineering and operations management. The theme of the conference is “Operational Excellence in the Era of Industry 4.0.” There were more than 400 papers/abstracts submitted from 43 countries, and after a thorough peer review process, approximately 300 have been accepted. The program includes many cutting-edge topics of industrial engineering and operations management. Our keynote speakers: • Prof. Kuzvinetsa Peter Dzvimbo, Chief Executive Officer, Zimbabwe Council for Higher Education (ZIMCHE), Harare, Zimbabwe • Dr. Esther T. Akinlabi, Director, Pan African University for Life and Earth Sciences Institute (PAULESI), Ibadan, Nigeria - African Union Commission • Henk Viljoen, Siemens – Xcelerator, Portfolio Development Manager Siemens Digital Industries Software, Pretoria, Gauteng, South Africa • Dr. -

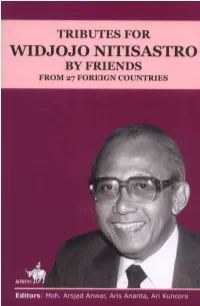

Tributes1.Pdf

Tributes for Widjojo Nitisastro by Friends from 27 Foreign Countries Law No.19 of 2002 regarding Copyrights Article 2: 1. Copyrights constitute exclusively rights for Author or Copyrights Holder to publish or copy the Creation, which emerge automatically after a creation is published without abridge restrictions according the law which prevails here. Penalties Article 72: 2. Anyone intentionally and without any entitlement referred to Article 2 paragraph (1) or Article 49 paragraph (1) and paragraph (2) is subject to imprisonment of no shorter than 1 month and/or a fine minimal Rp 1.000.000,00 (one million rupiah), or imprisonment of no longer than 7 years and/or a fine of no more than Rp 5.000.000.000,00 (five billion rupiah). 3. Anyone intentionally disseminating, displaying, distributing, or selling to the public a creation or a product resulted by a violation of the copyrights referred to under paragraph (1) is subject to imprisonment of no longer than 5 years and/or a fine of no more than Rp 500.000.000,00 (five hundred million rupiah). Tributes for Widjojo Nitisastro by Friends from 27 Foreign Countries Editors: Moh. Arsjad Anwar Aris Ananta Ari Kuncoro Kompas Book Publishing Jakarta, January 2007 Tributes for Widjojo Nitisastro by Friends from 27 Foreign Countries Published by Kompas Book Pusblishing, Jakarta, January 2007 PT Kompas Media Nusantara Jalan Palmerah Selatan 26-28, Jakarta 10270 e-mail: [email protected] KMN 70007006 Editor: Moh. Arsjad Anwar, Aris Ananta, and Ari Kuncoro Copy editor: Gangsar Sambodo and Bagus Dharmawan Cover design by: Gangsar Sambodo and A.N. -

World Higher Education Database Whed Iau Unesco

WORLD HIGHER EDUCATION DATABASE WHED IAU UNESCO Página 1 de 438 WORLD HIGHER EDUCATION DATABASE WHED IAU UNESCO Education Worldwide // Published by UNESCO "UNION NACIONAL DE EDUCACION SUPERIOR CONTINUA ORGANIZADA" "NATIONAL UNION OF CONTINUOUS ORGANIZED HIGHER EDUCATION" IAU International Alliance of Universities // International Handbook of Universities © UNESCO UNION NACIONAL DE EDUCACION SUPERIOR CONTINUA ORGANIZADA 2017 www.unesco.vg No paragraph of this publication may be reproduced, copied or transmitted without written permission. While every care has been taken in compiling the information contained in this publication, neither the publishers nor the editor can accept any responsibility for any errors or omissions therein. Edited by the UNESCO Information Centre on Higher Education, International Alliance of Universities Division [email protected] Director: Prof. Daniel Odin (Ph.D.) Manager, Reference Publications: Jeremié Anotoine 90 Main Street, P.O. Box 3099 Road Town, Tortola // British Virgin Islands Published 2017 by UNESCO CENTRE and Companies and representatives throughout the world. Contains the names of all Universities and University level institutions, as provided to IAU (International Alliance of Universities Division [email protected] ) by National authorities and competent bodies from 196 countries around the world. The list contains over 18.000 University level institutions from 196 countries and territories. Página 2 de 438 WORLD HIGHER EDUCATION DATABASE WHED IAU UNESCO World Higher Education Database Division [email protected] -

Indonesia Assessment 1991

Indonesia Assessment 1991 Hal Hill, editor Political and Social Change Monograph 13 Political and Social Change Monograph 13 Indonesia Assessment 1991 Proceedings of Indonesia Update Conference, August 1991 Indonesia Project, Department of Economics and Department of Political and Social Change, Research School of Pacific Studies, ANU Hal Hill (ed.) Department of Political and Social Change Research School of Pacific Studies Australian National University Canberra, 1991 © Hal Hill and the several authors each in respect of the papers contributed by them; for the full list of the names of such copyright owners and the papers in respect of which they are the copyright owners see the Table of Contents of this volume. This work is copyright. Apart from any fair dealings for the purpose of study, criticism or review, as permitted under the Copyright Act, no part may be reproduced by any process without written permission. Enquiries may be made to the publisher. First published 1991, Department of Political and Social Change, Research School of Pacific Studies, The Australian National University. Printed and manufactured in Australia by Panther Publishing and Press. Distributed by Department of Political and Social Change Research School of Pacific Studies Australian National University GPO Box 4 Canberra ACT 2601 Australia (FAX: 06-257-1 893) National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-publication entry Indonesia Update Conference (1991 Australian National University). Indonesia Assessment, proceedings of Indonesia Update Conference, August 1991 Bibliography. Includes index ISBN 0 7315 1291 X 1. Education, Higher - Indonesia - Congresses. 2. Indonesia - Economic conditions - 1966- - Congresses. 3. Indonesia - Politics and government- 1%6- - Congresses. I. -

Yayasan-Yayasan Soeharto Oleh George Junus Aditjondro

Tempointeraktif.com - Yayasan-Yayasan Soeharto oleh George Junus Aditjondro Search | Advance search | Registration | About us | Careers dibuat oleh Radja:danendro Home Budaya Nasional Digital Berita Terkait Ekonomi Yayasan-Yayasan Soeharto oleh George Mahasiswa Serentak Kenang Tragedi Iptek • Junus Aditjondro Trisakti Jakarta Jum'at, 14 Mei 2004 | 19:23 WIB • Kesehatan Soeharto Memburuk Nasional • BEM Se-Yogya Tolak Mega, Akbar, Nusa TEMPO Interaktif : Wiranto, dan Tutut Olahraga • Asvi: Ada Polarisasi di Komnas HAM Majalah BERAPA sebenarnya kekayaan keluarga Suharto dari yayasan- soal Kasus Soeharto yayasan yang didirikan dan dipimpin Suharto dan Pemeriksaan Kesehatan Soeharto Koran • keluarganya, dari saham yayasan- yayasan itu dalam Belum Jelas Pusat Data berbagai konglomerat di Indonesia dan di luar negeri? • Kejaksaan Lanjutkan Perkara Setelah Tempophoto Soeharto Sehat Narasi Pertanyaan ini sangat sulit dijawab oleh "orang luar". LSM: Selidiki Pelanggaran HAM • English Kesulitan melacak kekayaan semua yayasan itu diperparah Soeharto oleh tumpang-tindihnya kekayaan keluarga Suharto dengan • Komnas HAM: Lima Pelanggaran HAM kekayaan sejumlah keluarga bisnis yang lain, misalnya tiga Berat di Masa Soeharto keluarga Liem Sioe Liong, keluarga Eka Tjipta Widjaya, dan • Pengacara Suharto: Kejari Kurang keluarga Bob Hasan. Kerjaan • Mahasiswa Mendemo KPU Tapi jangan difikir bahwa keluarga Suharto hanya senang >selengkapnya... menggunakan pengusaha-pengusaha keturunan Cina sebagai operator bisnisnya. Sebab bisnis keluarga Suharto juga sangat tumpang tindih dengan bisnis dua keluarga keturunan Referensi Arab, yakni Bakrie dan Habibie. Keluarga Bakrie segudang kongsinya dengan keluarga Suharto, a.l. dengan Bambang • Yayasan-Yayasan Soeharto oleh dan Sudwikatmono dalam bisnis minyak mentah Pertamina George Junus Aditjondro lewat Hong Kong (Pura, 1986; Toohey, 1990: 8-9; Warta • Biodata Soeharto Ekonomi , 30 Sept. -

Plagiat Merupakan Tindakan Tidak Terpuji Plagiat

PLAGIATPLAGIAT MERUPAKAN MERUPAKAN TINDAKAN TINDAKAN TIDAK TIDAK TERPUJI TERPUJI PEMERINTAHAN PRESIDEN B.J. HABIBIE (1998-1999): KEBIJAKAN POLITIK DALAM NEGERI MAKALAH Diajukan untuk Memenuhi Salah Satu Syarat Memperoleh Gelar Sarjana Pendidikan Program Studi Pendidikan Sejarah Oleh: ALBERTO FERRY FIRNANDUS NIM: 101314023 PROGRAM STUDI PENDIDIKAN SEJARAH JURUSAN PENDIDIKAN ILMU PENGETAHUAN SOSIAL FAKULTAS KEGURUAN DAN ILMU PENDIDIKAN UNIVERSITAS SANATA DHARMA YOGYAKARTA 2015 PLAGIATPLAGIAT MERUPAKAN MERUPAKAN TINDAKAN TINDAKAN TIDAK TIDAK TERPUJI TERPUJI PEMERINTAHAN PRESIDEN B.J. HABIBIE (1998-1999): KEBIJAKAN POLITIK DALAM NEGERI MAKALAH Diajukan untuk Memenuhi Salah Satu Syarat Memperoleh Gelar Sarjana Pendidikan Program Studi Pendidikan Sejarah Oleh: ALBERTO FERRY FIRNANDUS NIM: 101314023 PROGRAM STUDI PENDIDIKAN SEJARAH JURUSAN PENDIDIKAN ILMU PENGETAHUAN SOSIAL FAKULTAS KEGURUAN DAN ILMU PENDIDIKAN UNIVERSITAS SANATA DHARMA YOGYAKARTA 2015 i PLAGIATPLAGIAT MERUPAKAN MERUPAKAN TINDAKAN TINDAKAN TIDAK TIDAK TERPUJI TERPUJI ii PLAGIATPLAGIAT MERUPAKAN MERUPAKAN TINDAKAN TINDAKAN TIDAK TIDAK TERPUJI TERPUJI iii PLAGIATPLAGIAT MERUPAKAN MERUPAKAN TINDAKAN TINDAKAN TIDAK TIDAK TERPUJI TERPUJI HALAMAN PERSEMBAHAN Makalah ini ku persembahkan kepada: Kedua orang tua ku yang selalu mendoakan dan mendukungku. Teman-teman yang selalu memberikan bantuan, semangat dan doa. Almamaterku. iv PLAGIATPLAGIAT MERUPAKAN MERUPAKAN TINDAKAN TINDAKAN TIDAK TIDAK TERPUJI TERPUJI HALAMAN MOTTO Selama kita bersungguh-sungguh maka kita akan memetik buah yang manis, segala keputusan hanya ditangan kita sendiri, kita mampu untuk itu. (B.J. Habibie) Dimanapun engkau berada selalulah menjadi yg terbaik dan berikan yang terbaik dari yg bisa kita berikan. (B.J. Habibie) Pandanglah hari ini, kemarin sudah jadi mimpi. Dan esok hanyalah sebuah visi. Tetapi, hari ini sesungguhnya nyata, menjadikan kemarin sebagai mimpi kebahagiaan, dan setiap hari esok adalah visi harapan. -

Digital Repository Universitas Jember Digital Repository Universitas Jember 106

DigitalDigital RepositoryRepository UniversitasUniversitas JemberJember SKRIPSI PERAN AKBAR TANDJUNG DALAM MENYELAMATKAN PARTAI GOLKAR PADA MASA KRISIS POLITIK PADA TAHUN 1998-1999 Oleh Mega Ayu Lestari NIM 090110301022 JURUSAN ILMU SEJARAH FAKULTAS SASTRA UNIVERSITAS JEMBER 2016 DigitalDigital RepositoryRepository UniversitasUniversitas JemberJember PERAN AKBAR TANDJUNG DALAM MENYELAMATKAN PARTAI GOLKAR PADA MASA KRISIS POLITIK PADA TAHUN 1998-1999 SKRIPSI Skripsi diajukan guna melengkapi tugas akhir dan memenuhi salah satu syarat untuk menyelesaikan studi pada Jurusan Sejarah (S1) dan mencapai gelar sarjana sastra Oleh Mega Ayu Lestari NIM 090110301022 JURUSAN ILMU SEJARAH FAKULTAS SASTRA UNIVERSITAS JEMBER 2016 DigitalDigital RepositoryRepository UniversitasUniversitas JemberJember PERNYATAAN Saya yang bertanda tangan dibawah ini : Nama : Mega Ayu Lestari NIM : 090110301022 Menyatakan dengan sesungguhnya bahwa karya ilmiah yang berjudul:Peran Akbar Tandjung Dalam Menyelamatkan Partai Golkar Pada Masa Krisis Politik Pada Tahun 1998-1999”adalah benar-benar hasil karya ilmiah sendiri, kecuali jika dalam pengutipan substansi disebutkan sumbernya, dan belum pernah diajukan pada institusi manapun, serta bukan karya jiplakan. Saya bertanggung jawab atas keabsahan dan kebenaran isinya sesuai dengan sikap ilmiah yang harus dijunjung tinggi. Demikian pernyataan ini saya buat dengan sebenarnya, tanpa adanya tekanan dan paksaan dari pihak manapun serta bersedia mendapat sanksi akademik jika ternyata dikemudian hari pernyataan ini tidak benar. Jember,14Maret -

5 Komnas HAM : the Cases 41

THESES SIS/LIBRARY TELEPHONE: +61 2 6125 4631 R.G. MENZIES LIBRARY BUILDING NO:2 FACSIMILE: +61 2 6125 4063 THE AUSTRALIAN NATIONAL UNIVERSITY EMAIL: [email protected] CANBERRA ACT 0200 AUSTRALIA USE OF THESES This copy is supplied for purposes of private study and research only. Passages from the thesis may not be copied or closely paraphrased without the written consent of the author. Komnas HAM and the Politics of Human Rights in Indonesia Jessica M. Ramsden Smith / March 1998 A thesis submitted for the degree of Master of Arts (Asian Studies) at the Australian National University Except where otherwise indicated this thesis is my own work d· r·-----·-···----·- -· ...... f.9..:.£.:1.~ .. iii Acknowledgments This study is the product of research carried out in Canberra and Jakarta between 1994 - 1997. The work is my own, but I would like to record my thanks to those who helped at various stages. I am grateful for the generous time and advice given by interviewees. Kornnas members were helpful and encouraging. I would particularly like to thank Vice Chairpersons Miriam Budiardjo and Marzuk:i Darusman, as well as Charles Himawan, (the late) Roekmini Koesoemo Astoeti and Deplu's Hassan Wirayuda Thanks to Dr. Harold Crouch who supervised and discussed my work, and offered his learned insight into Indonesian politics. Finally, my thanks to my husband Shannon, for his patience and support iv Contents Glossary and Abbreviations v 1 Introduction 1 P.art One : Tbe Origins of Kornnas HAM 2 Human Rights in Indonesia : The Domestic Context -

Nabbs-Keller 2014 02Thesis.Pdf

The Impact of Democratisation on Indonesia's Foreign Policy Author Nabbs-Keller, Greta Published 2014 Thesis Type Thesis (PhD Doctorate) School Griffith Business School DOI https://doi.org/10.25904/1912/2823 Copyright Statement The author owns the copyright in this thesis, unless stated otherwise. Downloaded from http://hdl.handle.net/10072/366662 Griffith Research Online https://research-repository.griffith.edu.au GRIFFITH BUSINESS SCHOOL Submitted in fulfilment of the requirements of the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY By GRETA NABBS-KELLER October 2013 The Impact of Democratisation on Indonesia's Foreign Policy Greta Nabbs-Keller B.A., Dip.Ed., M.A. School of Government and International Relations Griffith Business School Griffith University This thesis is submitted in fulfilment of the requirements of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. October 2013 Abstract How democratisation affects a state's foreign policy is a relatively neglected problem in International Relations. In Indonesia's case, there is a limited, but growing, body of literature examining the country's foreign policy in the post- authoritarian context. Yet this scholarship has tended to focus on the role of Indonesia's legislature and civil society organisations as newly-empowered foreign policy actors. Scholars of Southeast Asian politics, meanwhile, have concentrated on the effects of Indonesia's democratisation on regional integration and, in particular, on ASEAN cohesion and its traditional sovereignty-based norms. For the most part, the literature has completely ignored the effects of democratisation on Indonesia's foreign ministry – the principal institutional actor responsible for foreign policy formulation and conduct of Indonesia's diplomacy. Moreover, the effect of Indonesia's democratic transition on key bilateral relationships has received sparse treatment in the literature. -

A National Mental Revolution

A NATIONAL MENTAL REVOLUTION THROUGH THE RESTORATION OF CITIES OF COLONIAL LEGACY: TOWARDS BUILDING A STRONG NATION’S CHARACTER An Urban Cultural Historical and Bio Psychosocial Overview By Martono Yuwono and Krishnahari S. Pribadi, MD *) “We shape our buildings; thereafter they shape us” --- (Sir Winston Churchill). “The young generation does not realize how hard and difficult it was when Indonesia struggled for our independence throughout three hundred years of colonization. They have to learn thoroughly from our history and to use the experiences and leadership of the older generations, as guidance and role models. They have to understand about our national identity. When they do not know their national’s identity, where would they go?” (Ali Sadikin’s statement as interviewed by Express Magazine, June 1, 1973, and several times discussions with Martono Yuwono) “Majapahit", a strong maritime nation in the 14th century The history of Indonesia as a maritime nation dates back to the 14th century when this South East Asian region was subjected under the reign of the great “Majapahit” Empire. The Empire ruled a region which is geographically located between two great continents namely Asia and Australia, and at the same time between two great oceans namely the Pacific and the Indian oceans. This region consisted of mainly the archipelagic group of islands (which is now referred to as Indonesia), and some portion of the coastal region at the south eastern tip of the Asian continent. “Majapahit” was already the largest archipelagic state in the world at that time, in control of the strategic cross roads (sea lanes) between those two great continents and two great oceans. -

The May 1998 Riots and the Emergence of Chinese Indonesians: Social Movements in the Post-Soeharto Era*

The May 1998 Riots and the Emergence of Chinese Indonesians: Social Movements in the Post-Soeharto Era* Johanes Herlijanto Lecturer, Department of History, Faculty of Humanities, University of Indonesia I. Introduction The social movements launched by Chinese-Indonesians to struggle for recognition of their ethnic identity in post-Soeharto Indonesia should not be understood merely as a result of the collapse of the New Order authoritarian regime. On the contrary, the eagerness of Chinese Indonesians to participate in such movements should also be perceived as a changing process of their perception of their position in Indonesian society. This change in perception is most importantly related to a strategy of seeking security in a society where the ethnic Chinese often become the target of discrimination, violence and riots. This paper argues that the May 1998 riots have had an important influence on changing process of perception among Chinese Indonesians. It is after this incident that the perception which encouraged Chinese-Indonesians to struggle for the recognition of their ethnic identity as well as for the abolishment of all discrimination against them began to emerge and develop. One way to understand this is by posing questions of how the Chinese-Indonesians perceived the May 1998 tragedy and how have they constructed an alternative understanding about their position in Indonesian society. These questions will be the main focus of this paper. In dealing with these questions, this paper will discuss three important * Revised version of the paper presented at the 18th Conference of International Association of Historians of Asia (IAHA), December 6-10, 2004, Academia Sinica, Taipei, Taiwan.