The Development of Indonesian National Democratic Institutions and Compatibility with Its National Culture

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Tributes1.Pdf

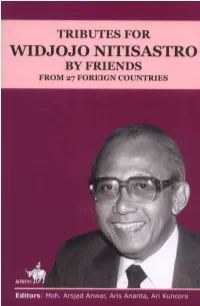

Tributes for Widjojo Nitisastro by Friends from 27 Foreign Countries Law No.19 of 2002 regarding Copyrights Article 2: 1. Copyrights constitute exclusively rights for Author or Copyrights Holder to publish or copy the Creation, which emerge automatically after a creation is published without abridge restrictions according the law which prevails here. Penalties Article 72: 2. Anyone intentionally and without any entitlement referred to Article 2 paragraph (1) or Article 49 paragraph (1) and paragraph (2) is subject to imprisonment of no shorter than 1 month and/or a fine minimal Rp 1.000.000,00 (one million rupiah), or imprisonment of no longer than 7 years and/or a fine of no more than Rp 5.000.000.000,00 (five billion rupiah). 3. Anyone intentionally disseminating, displaying, distributing, or selling to the public a creation or a product resulted by a violation of the copyrights referred to under paragraph (1) is subject to imprisonment of no longer than 5 years and/or a fine of no more than Rp 500.000.000,00 (five hundred million rupiah). Tributes for Widjojo Nitisastro by Friends from 27 Foreign Countries Editors: Moh. Arsjad Anwar Aris Ananta Ari Kuncoro Kompas Book Publishing Jakarta, January 2007 Tributes for Widjojo Nitisastro by Friends from 27 Foreign Countries Published by Kompas Book Pusblishing, Jakarta, January 2007 PT Kompas Media Nusantara Jalan Palmerah Selatan 26-28, Jakarta 10270 e-mail: [email protected] KMN 70007006 Editor: Moh. Arsjad Anwar, Aris Ananta, and Ari Kuncoro Copy editor: Gangsar Sambodo and Bagus Dharmawan Cover design by: Gangsar Sambodo and A.N. -

Indonesia Assessment 1991

Indonesia Assessment 1991 Hal Hill, editor Political and Social Change Monograph 13 Political and Social Change Monograph 13 Indonesia Assessment 1991 Proceedings of Indonesia Update Conference, August 1991 Indonesia Project, Department of Economics and Department of Political and Social Change, Research School of Pacific Studies, ANU Hal Hill (ed.) Department of Political and Social Change Research School of Pacific Studies Australian National University Canberra, 1991 © Hal Hill and the several authors each in respect of the papers contributed by them; for the full list of the names of such copyright owners and the papers in respect of which they are the copyright owners see the Table of Contents of this volume. This work is copyright. Apart from any fair dealings for the purpose of study, criticism or review, as permitted under the Copyright Act, no part may be reproduced by any process without written permission. Enquiries may be made to the publisher. First published 1991, Department of Political and Social Change, Research School of Pacific Studies, The Australian National University. Printed and manufactured in Australia by Panther Publishing and Press. Distributed by Department of Political and Social Change Research School of Pacific Studies Australian National University GPO Box 4 Canberra ACT 2601 Australia (FAX: 06-257-1 893) National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-publication entry Indonesia Update Conference (1991 Australian National University). Indonesia Assessment, proceedings of Indonesia Update Conference, August 1991 Bibliography. Includes index ISBN 0 7315 1291 X 1. Education, Higher - Indonesia - Congresses. 2. Indonesia - Economic conditions - 1966- - Congresses. 3. Indonesia - Politics and government- 1%6- - Congresses. I. -

13Th CONSULTATIVE GROUP on INDONESIA Jakarta, Indonesia December 10-11, 2003

13th CONSULTATIVE GROUP ON INDONESIA Jakarta, Indonesia December 10-11, 2003 List of Participants AUSTRALIA STATUS 1. Mr. Bruce Davis Head of Delegation Director General Private Sector Investor Climate AUSAID Canberra Health Role of Security and Development 2. His Excellency Head of Delegation Mr. David Ritchie Role of Security and Development Ambassador Extraordinary and Plenipotentiary Head of Delegation Dinner Embassy of Australia 3. Mr. Robin Davies Private Sector Investment Climate Minister Counsellor, AusAID Role Security and Development Health Head of Delegation Dinner 4. Ms. Penny Burtt Private Sector Investment Climate Minister Counsellor, DFAT 5. Mr. Sam Zappia Aid Effectiveness Counsellor, Development Cooperation Private Sector Investment Climate AusAID Health 6. Ms. Allison Sudrajat Decentralisation Director Indonesia Section Legal Judicial AusAID Canberra Role of Security and Development 7. Ms. Karen Whitham Counsellor, Treasury 8. Ms. Catherine Yates Role of Security and Development First Secretary 9. Ms. Zabeta Moutafis Decentralisation First Secretary Poverty Infrastructure 10. Mr. Brian Hearn Pre-CGI only Second Secretary Health 11. Mr. Mike Abrahams Pre-CGI only Senior Trade Commissioner Private Sector Investment Climate 12. Mr. Andrew Chandler 13th CONSULTATIVE GROUP ON INDONESIA Jakarta, Indonesia December 10-11, 2003 List of Participants AUSTRIA 13. His Excellency Head of Delegation Dr. Bernhard Zimburg Ambassador Extraordinary and Plenipotentiary Embassy of Austria 14. Mr. Daniel Benes PT Waagner Biro Indonesia 15. Mr. Robert Friesacher Verbundplan Project Office BELGIUM 16. His Excellency Head of Delegation Mr. Hans-Christian Kint Ambassador Extraordinary and Plenipotentiary Embassy of the Kingdom of Belgium 17. Mr. Alain Hanssen Confirmed Counselor of the Embassy of Belgium CANADA 18. Mr. -

Bhutan's Political Transition –

Spotlight South Asia Paper Nr. 2: Bhutan’s Political Transition – Between Ethnic Conflict and Democracy Author: Dr. Siegried Wolf (Heidelberg) ISSN 2195-2787 1 SSA ist eine regelmäßig erscheinende Analyse- Reihe mit einem Fokus auf aktuelle politische Ereignisse und Situationen Südasien betreffend. Die Reihe soll Einblicke schaffen, Situationen erklären und Politikempfehlungen geben. SSA is a frequently published analysis series with a focus on current political events and situations concerning South Asia. The series should present insights, explain situations and give policy recommendations. APSA (Angewandte Politikwissenschaft Südasiens) ist ein auf Forschungsförderung und wissenschaftliche Beratung ausgelegter Stiftungsfonds im Bereich der Politikwissenschaft Südasiens. APSA (Applied Political Science of South Asia) is a foundation aiming at promoting science and scientific consultancy in the realm of political science of South Asia. Die Meinungen in dieser Ausgabe sind einzig die der Autoren und werden sich nicht von APSA zu eigen gemacht. The views expressed in this paper are solely the views of the authors and are not in any way owned by APSA. Impressum: APSA Im Neuehnheimer Feld 330 D-69120 Heidelberg [email protected] www.apsa.info 2 Acknowledgment: The author is grateful to the South Asia Democratic Forum (SADF), Brussels for the extended support on this report. 3 Bhutan ’ s Political Transition – Between Ethnic Conflict and Democracy Until recently Bhutan (Drukyul - Land of the Thunder Dragon) did not fit into the story of the global triumph of democracy. Not only the way it came into existence but also the manner in which it was interpreted made the process of democratization exceptional. As a land- locked country which is bordered on the north by Tibet in China and on the south by the Indian states Sikkim, West Bengal, Assam and Arunachal Pradesh, it was a late starter in the process of state-building. -

Soekarno's Political Thinking About Guided Democracy

e-ISSN : 2528 - 2069 SOEKARNO’S POLITICAL THINKING ABOUT GUIDED DEMOCRACY Author : Gili Argenti and Dini Sri Istining Dias Government Science, State University of Singaperbangsa Karawang (UNSIKA) Email : [email protected] and [email protected] ABSTRACT Soekarno is one of the leaders of the four founders of the Republic of Indonesia, his political thinking is very broad, one of his political thinking about democracy is guided democracy into controversy, in his youth Soekarno was known as a very revolutionary, humanist and progressive figure of political thinkers of his day. His thoughts on leading democracy put his figure as a leader judged authoritarian by his political opponents. This paper is a study of thought about Soekarno, especially his thinking about the concept of democracy which is considered as a political concept typical of Indonesian cultures. Key word: Soekarno, democracy PRELIMINARY Soekarno is one of the four founders of the Republic of Indonesia according to the version of Tempo Magazine, as political figures aligned with Mohammad Hatta, Sutan Sjahrir and Tan Malaka. Soekarno's thought of national politics placed himself as a great thinker that Indonesian ever had. In the typology of political thought, his nationality has been placed as a radical nationalist thinker, since his youthful interest in politics has been enormous. As an active politician, Soekarno poured many of his thinkers into speeches, articles and books. One of Soekarno's highly controversial and inviting notions of polemic up to now is the political thought of guided democracy. Young Soekarno's thoughts were filled with revolutionary idealism and anti-oppression, but at the end of his reign, he became a repressive and anti-democratic thinker. -

Lemhannas RI Said That in Line with the Vision of the National Development As Contained in Law No

NATIONAL RESILIENCE INSTITUTE OF THE REPUBLIC OF INDONESIA LEMHANNAS25th Edition, AugustRI 20, 2011 1 NEWSLETTER No Truth is Ambivalent 25th Edition, August 20, 2011 NATIONAL SEMINAR: MASTERPLAN FOR THE ACCELERATION AND EXPANSION OF INDONESIA’S (MP3EI) 2011-2025 from relevant stakeholders at the national level. In his opening speech, Governor of Lemhannas RI said that in line with the vision of the national development as contained in Law No. 17 of 2007 on the Long-term National Development Plan 2005-2025, the vision for the Acceleration and Expansion of Indonesia’s Economic Development is “Creating an Independent, Avanced, Just and Prosperous Indonesian Nation”. It is expected that, through MP3EI, the acceleration and expansion of the economic development will establish Indonesia as a de- veloped country by 2025 . The Governor of Lemhannas RI also expected that the results of the national seminar which discussed the policies, strategies and implementation of MP3EI could The Coordinating Minister for Economic Affairs Ir. M. Hatta Rajasa opens a National Seminar MP3EI in Lemhannas RI serve as materials in formulating recommendations to emhannas RI held a National Seminar on the Master national leaders. Plan for the Acceleration and Expansion of Indonesia’s TABLE OF CONTENTS L 2011 - 2025 Economic Development (MP3EI) in order to Support the Acceleration of the National Development in 1. National Seminar: Masterplan for the Acceleration and Expansion of order to Enhance National Resilience on July 25, 2011 in Indonesia’s (MP3EI) 2011-2025.....................................................................1 Dwi Warna Purwa Building, Lemhannas RI. 2. Singaporean Minister of Defense’s Visit to Lemhannas RI...................... 2 The national seminar was opened by the Coordinating 3. -

Democratic Culture and Muslim Political Participation in Post-Suharto Indonesia

RELIGIOUS DEMOCRATS: DEMOCRATIC CULTURE AND MUSLIM POLITICAL PARTICIPATION IN POST-SUHARTO INDONESIA DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Political Science at The Ohio State University by Saiful Mujani, MA ***** The Ohio State University 2003 Dissertation Committee: Approved by Professor R. William Liddle, Adviser Professor Bradley M. Richardson Professor Goldie Shabad ___________________________ Adviser Department of Political Science ABSTRACT Most theories about the negative relationship between Islam and democracy rely on an interpretation of the Islamic political tradition. More positive accounts are also anchored in the same tradition, interpreted in a different way. While some scholarship relies on more empirical observation and analysis, there is no single work which systematically demonstrates the relationship between Islam and democracy. This study is an attempt to fill this gap by defining Islam empirically in terms of several components and democracy in terms of the components of democratic culture— social capital, political tolerance, political engagement, political trust, and support for the democratic system—and political participation. The theories which assert that Islam is inimical to democracy are tested by examining the extent to which the Islamic and democratic components are negatively associated. Indonesia was selected for this research as it is the most populous Muslim country in the world, with considerable variation among Muslims in belief and practice. Two national mass surveys were conducted in 2001 and 2002. This study found that Islam defined by two sets of rituals, the networks of Islamic civic engagement, Islamic social identity, and Islamist political orientations (Islamism) does not have a negative association with the components of democracy. -

Democracy and Human Security: Analysis on the Trajectory of Indonesia’S Democratization

Advances in Social Science, Education and Humanities Research, volume 456 Proceedings of the Brawijaya International Conference on Multidisciplinary Sciences and Technology (BICMST 2020) Advances in Social Science, Education and Humanities Research, volume 456 Proceedings of the Brawijaya International Conference on Multidisciplinary Sciences and Technology (BICMST 2020) Democracy and Human Security: Analysis on the Trajectory of Indonesia’s Democratization Rika Kurniaty Department of International Law Faculty of Law, University of Brawijaya Malang, Indonesia [email protected] The concept of national security has a long Abstract—Democracy institution is believed would history, since the conclusion of the thirty-year naturally lead to greater human security. The end of cessation of war set forth in the Treaties of Westphalia communism in the Soviet Union and other countries has in 1648. National security was defined as an effort been described as the triumph of democracy throughout the world, which quickly led to claims that there is now a aimed at maintaining the integrity of a territory the right to democracy as guide principles in international state and freedom to determine the form of self- law. In Indonesia, attention to the notion of democracy government. However, with global developments and developed very rapidly in the late 1990s. In Indonesia, after 32 years of President Suharto’s authoritarian increasingly complex relations between countries and regime from 1966 to 1998, Indonesia finally began the the variety of threats faced by countries in the world, democratization phase in May 1998. It worth noting that the formulation and practice of security Indonesia has experienced four different periods of implementation tend to be achieved together different government and political systems since its (collective security) becomes an important reference independent, and all those stage of systems claim to be for countries in the world. -

Obituary Drs. Frans Seda 1926 – 2010

Obituary Drs. Frans Seda 1926 – 2010 Frans Seda was the quintessential good neighbour; he believed that it was in the mutual interest of Indonesia and Australia to get on; that ours was a symbiotic relationship driven by necessity. Franciscus Xaverius aka Frans Seda was an enigma; a Catholic from Flores in the Eastern Provinces and the only person to serve in both the Soekarno and Suharto Ministries. He was a freedom fighter, Minister, Diplomat, respected economist, author, successful entrepreneur and the Territory’s man in Indonesia. It was in this later capacity that he worked with a succession of Territory public servants, Ministers and Chief Ministers of both political hues. Honoured by the Republic of Indonesia Frans was also a Papal Knight and in 1999 was conferred a Member of the Order of Australia for „strengthening trade links between Australia and Indonesia‟. He did much more than that. Born in Flores, East Nusa Tengarra on 4 October 1926 he died aged 83 having lived an exciting and at times dangerous life. When the PKI (Communist Party of Indonesia) launched their pre emptive Communist coup in the mid 1960’s Frans told me he knew he was on the list to be picked up by the death squads. He quietly left for his deserted Government Office where he awaited his fate. He made it widely known that he would be at work that day to protect his family in case the „plotters‟ went to his home. They never came as Suharto and the generals moved to restore Order. Notwithstanding he remained a measured critic of Suharto over the years and of the endemic corruption that pervaded the Indonesian political system. -

INDO 78 0 1108140653 61 92.Pdf (681.3Kb)

Indonesia's Accountability Trap: Party Cartels and Presidential Power after Democratic Transition Dan Slater1 Idolization and "Immediate Help!": Campaigning as if Voters Mattered On July 14, 2004, just nine days after Indonesia's first-ever direct presidential election, a massive inferno ripped through the impoverished, gang-infested district of Tanah Abang in central Jakarta. Hundreds of dwellings were destroyed and over a thousand Jakartans were rendered homeless. While such catastrophes are nothing unusual in the nation's chaotic capital, the political responses suggested that some interesting changes are afoot in Indonesia's fledgling electoral democracy. The next day, presidential frontrunner Susilo Bambang Yudhoyono (SBY) took a break from watching his burgeoning vote totals at the five-star Borobodur Hotel to visit Tanah Abang's fire victims. Since he had just clinched pole position in Indonesia's run-off presidential election in late September, SBY's public appearance made fantastic copy. The handsome former general comforted distraught families, then crept, head and shoulders protruding through the sunroof of his campaign minivan, through a swarm of star-struck locals. Never mind the knock-off reality-television program screening for talent just a few miles away at the swanky Semanggi shopping complex; here, in one of Jakarta's least swanky settings, appeared to be the true Indonesian Idol. 1 This article draws on a comparative project with Marc Craighead, conversations and collaboration with whom have been invaluable in refining the theoretical arguments presented here. It has also greatly benefited from the thoughtful comments of Jamie Davidson, Dirk Tomsa, and an anonymous reviewer at Indonesia; the savvy and sensitive editing of Deborah Homsher; and generous fieldwork support from the Academy for Educational Development, Emory University, and the Ford Foundation. -

INDONESIA in 2000 a Shaky Start for Democracy

INDONESIA IN 2000 A Shaky Start for Democracy R. William Liddle At the end of 1999 Indonesia appeared to have com- pleted a successful transition to democracy after more than four decades of dictatorship. Free elections had been held for the national legislature (DPR, Dewan Perwakilan Rakyat). The People’s Consultative Assembly (MPR, Majelis Permusyawaratan Rakyat), a uniquely Indonesian institution com- prising members of the DPR plus regional and group representatives, had chosen a new president, the charismatic traditionalist Muslim cleric Abdur- rahman Wahid (called Gus Dur) and vice-president, Megawati Sukarnoputri, daughter of Indonesia’s founding father and first president Sukarno, for the 1999–2004 term. Gus Dur, whose Partai Kebangkitan Bangsa (PKB, Na- tional Awakening Party) holds only 11% of the DPR seats, had then ap- pointed a national unity cabinet consisting of representatives of all of the major parties. Twelve months later, Gus Dur is widely regarded, both at home and abroad, as a failed president. He narrowly escaped dismissal by the MPR, which met for its first annual session in August 2000. Most observers and politicians concur that his personal legitimacy continues to decline and that the main obstacle to his removal now is fear that his likely replacement, Megawati, would be an even worse president. This extraordinary fall is largely the consequence of Gus Dur’s own disas- trous choices. He has been unwilling to act like a politician in a democracy, that is, to build a broad base of support and adopt a set of policies responsive to the interests of this constituency. Instead, he has acted impulsively and inconsistently, often without consulting his own staff, let alone his putative R. -

The Existence of the State Minister in the Government System After the Amendment to the 1945 Constitution

IOSR Journal Of Humanities And Social Science (IOSR-JHSS) Volume 25, Issue 5, Series. 1 (May. 2020) 51-78 e-ISSN: 2279-0837, p-ISSN: 2279-0845. www.iosrjournals.org The Existence of the State Minister in the Government System after the Amendment to the 1945 Constitution ParbuntianSinaga Doctor of Law, UniversitasKrisnadwipayana Jakarta Po Box 7774 Jat Cm Jakarta 13077, Indonesia Abstract: Constitutionally, the existence of ministers called cabinet or council of ministers in a presidential government system is an inseparable part of the executive power held by the President. The 1945 Constitution after the amendment, that the presence of state ministers as constitutional organs is part of the power of the President in running the government. This study aims to provide ideas about separate arrangements between state ministries placed separately in Chapter V Article 17 to Chapter III of the 1945 Constitution of the Republic of Indonesia concerning the authority of the state government or the power of the President, and also regarding the formation, amendment and dissolution of the ministries regulated in legislation. This study uses a normative juridical research approach. The results of the study show that the Minister of State is the President's assistant who is appointed and dismissed to be in charge of certain affairs in the government, which actually runs the government, and is responsible to the President. The governmental affairs referred to are regulated in Law No. 39 of 2008 concerning the State Ministry, consisting of: government affairs whose nomenclature is mentioned in the 1945 NRI Constitution, government affairs whose scope is mentioned in the 1945 NRI Constitution, and government affairs in the context of sharpening, coordinating, and synchronizing government programs.