World Press Freedom Review January-September 2011

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Thailand's Moment of Truth — Royal Succession After the King Passes Away.” - U.S

THAILAND’S MOMENT OF TRUTH A SECRET HISTORY OF 21ST CENTURY SIAM #THAISTORY | VERSION 1.0 | 241011 ANDREW MACGREGOR MARSHALL MAIL | TWITTER | BLOG | FACEBOOK | GOOGLE+ This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported License. This story is dedicated to the people of Thailand and to the memory of my colleague Hiroyuki Muramoto, killed in Bangkok on April 10, 2010. Many people provided wonderful support and inspiration as I wrote it. In particular I would like to thank three whose faith and love made all the difference: my father and mother, and the brave girl who got banned from Burma. ABOUT ME I’m a freelance journalist based in Asia and writing mainly about Asian politics, human rights, political risk and media ethics. For 17 years I worked for Reuters, including long spells as correspondent in Jakarta in 1998-2000, deputy bureau chief in Bangkok in 2000-2002, Baghdad bureau chief in 2003-2005, and managing editor for the Middle East in 2006-2008. In 2008 I moved to Singapore as chief correspondent for political risk, and in late 2010 I became deputy editor for emerging and frontier Asia. I resigned in June 2011, over this story. I’ve reported from more than three dozen countries, on every continent except South America. I’ve covered conflicts in Iraq, Afghanistan, Pakistan, Lebanon, the Palestinian Territories and East Timor; and political upheaval in Israel, Indonesia, Cambodia, Thailand and Burma. Of all the leading world figures I’ve interviewed, the three I most enjoyed talking to were Aung San Suu Kyi, Xanana Gusmao, and the Dalai Lama. -

United Nations A/HRC/17/44

United Nations A/HRC/17/44 General Assembly Distr.: General 12 January 2012 Original: English Human Rights Council Seventeenth session Agenda item 4 Human rights situation that require the Council’s attention Report of the International Commission of Inquiry to investigate all alleged violations of international human rights law in the Libyan Arab Jamahiriya* Summary Pursuant to Human Rights Council resolution S-15/1 of 25 February 2011, entitled “Situation of human rights in the Libyan Arab Jamahiriya”, the President of the Human Rights Council established the International Commission of Inquiry, and appointed M. Cherif Bassiouni as the Chairperson of the Commission, and Asma Khader and Philippe Kirsch as the two other members. In paragraph 11 of resolution S-15/1, the Human Rights Council requested the Commission to investigate all alleged violations of international human rights law in the Libyan Arab Jamahiriya, to establish the facts and circumstances of such violations and of the crimes perpetrated and, where possible, to identify those responsible, to make recommendations, in particular, on accountability measures, all with a view to ensuring that those individuals responsible are held accountable. The Commission decided to consider actions by all parties that might have constituted human rights violations throughout Libya. It also considered violations committed before, during and after the demonstrations witnessed in a number of cities in the country in February 2011. In the light of the armed conflict that developed in late February 2011 in the Libyan Arab Jamahiriya and continued during the Commission‟s operations, the Commission looked into both violations of international human rights law and relevant provisions of international humanitarian law, the lex specialis that applies during armed conflict. -

Daily Current Affair Quiz – 06.05.2019 to 08.05.2019

DAILY CURRENT AFFAIR QUIZ – 06.05.2019 TO 08.05.2019 DAILY CURRENT AFFAIR QUIZ : ( 06-08 MAY 2019) No. of Questions: 20 Correct: Full Mark: 20 Wrong: Time: 10 min Mark Secured: 1. What is the total Foreign Exchange B) Niketan Srivastava Reserves of India as on April 23, as per C) Arun Chaudhary the data by RBI? D) Vikas Verma A) USD 320.222 billion 8. Which among the following countries B) USD 418.515 billion will become the first in the world to C) USD 602.102 billion open the Crypto Powered City? D) USD 511.325 billion A) China 2. Name the newly appointed Supreme B) Nepal Allied Commander Europe (SACEUR) C) Malaysia of NATO? D) United States A) James G. Stavridis 9. Which of these network operators has B) Wesley Clark launched optical fibre-based high-speed C) Curtis M. Scaparrotti broadband service ‘Bharat Fibre’ in D) Tod D. Wolters Pulwama? 3. Which of these countries currency has A) Airtel been awarded with the best bank note B) BSNL for 2018 by the International Bank Note C) Reliance Society (IBNS) ? D) Vodafone A) Canada 10. Rani Abbakka Force is an all women B) India police patrol unit of which of these C) Singapore cities? D) Germany A) Srinagar 4. Maramraju Satyanarayana Rao who B) Pune passed away recently was a renowned C) Kolkata ___________ D) Mangaluru A) Judge 11. What was the name of the last captive B) Journalist White Tiger of Sanjay Gandhi National C) Writer Park (SGNP) that passed away recently? D) Scientist A) Bheem 5. -

World Trends in Freedom of Expression and Media Development: 2017/2018 Global Report

Published in 2018 by the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization 7, place de Fontenoy, 7523 Paris 07 SP, France © UNESCO and University of Oxford, 2018 ISBN 978-92-3-100242-7 Attribution-ShareAlike 3.0 IGO (CC-BY-SA 3.0 IGO) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0/igo/). By using the content of this publication, the users accept to be bound by the terms of use of the UNESCO Open Access Repos- itory (http://www.unesco.org/open-access/terms-use-ccbysa-en). The present license applies exclusively to the textual content of the publication. For the use of any material not clearly identi- fied as belonging to UNESCO, prior permission shall be requested from: [email protected] or UNESCO Publishing, 7, place de Fontenoy, 75352 Paris 07 SP France. Title: World Trends in Freedom of Expression and Media Development: 2017/2018 Global Report This complete World Trends Report Report (and executive summary in six languages) can be found at en.unesco.org/world- media-trends-2017 The complete study should be cited as follows: UNESCO. 2018. World Trends in Freedom of Expression and Media Development: 2017/2018 Global Report, Paris The designations employed and the presentation of material throughout this publication do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of UNESCO concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authori- ties, or concerning the delimiation of its frontiers or boundaries. The ideas and opinions expressed in this publication are those of the authors; they are not necessarily those of UNESCO and do not commit the Organization. -

December 18-10 Pp01

ANDAMAN Edition Volume 17 Issue 51 December 18 - 24, 2010 Daily news at www.phuketgazette.net 25 Baht Security boost for high season By Atchaa Khamlo front of their houses, and some car and motorbike rental busi- POLICE in Kathu are boosting nesses were careless in renting out their presence on the streets of their vehicles. Patong for the high season. “They were not specific when The move follows Kathu Police recording the homeland of the per- Superintendent Arayapan Puk- son renting the vehicle and some buakhao meeting his top officers of their cars were driven out of on Monday. Phuket. Col Arayapan called for his of- “So officers will remind people ficers to ramp up security, in to be more careful with their mo- terms of crime suppression and torbikes, and we will talk with safety, and to work towards re- business operators to find ways Patong Municipality’s ‘Pearl of the Andaman’ float leading the parade, ducing the number of accidents to protect their vehicles,” he said. complete with its own angel of the clam. Photo: Janpen Upatising involving tourists during the com- Kathu Police Superintendent As for thieves working Patong Arayapan Pukbuakhao ing months. Beach, Col Arayapan said plain- The result is more checkpoints tainment zone are to close at 2am, clothes police will be patrolling the The carnival is on and more officers on the street, and that police are to ask enter- sands, keeping a close watch on THOUSANDS of people joined in glamorous outfits marched along with an extra presence after the tainment establishments to switch tourists’ belongings. -

A CELEBRATION of PRESS FREEDOM World Press Freedom Day UNESCO/Guillermo Cano World Press Freedom Prize WORLD PRESS FREEDOM DAY

Ghanaian students at World Press Freedom Day 2018 Accra, Ghana. Photo credit: © Ghana Ministry of Information A CELEBRATION OF PRESS FREEDOM World Press Freedom Day UNESCO/Guillermo Cano World Press Freedom Prize WORLD PRESS FREEDOM DAY An overview Speakers at World Press Freedom Day 2017 in Jakarta, Indonesia Photo credit: ©Voice of Millenials very year, 3 May is a date which celebrates Ababa on 2-3 May with UNESCO and the African Union the fundamental principles of press freedom. Commission. The global theme for the 2019 celebration It serves as an occasion to evaluate press is Media for Democracy: Journalism and Elections in freedom around the world, defend the media Times of Disinformation. This conference will focus from attacks on their independence and on the contemporary challenges faced by media Epay tribute to journalists who have lost their lives in the in elections, including false information, anti-media exercise of their profession. rhetoric and attempts to discredit truthful news reports. World Press Freedom Day (WPFD) is a flagship The debates will also highlight the distinctiveness of awareness-raising event on freedom of expression, and journalism in helping to ensure the integrity of elections, in particular press freedom and the safety of journalists. as well as media’s potential in supporting peace and Since 1993, UNESCO leads the global celebration with reconciliation. a main event in a different country every year, organized In the last two editions, World Press Freedom together with the host government and various partners Day has focused on some of the most pressing issues working in the field of freedom of expression. -

ANNUAL REPORT 2020 Table of Contents

ANNUAL REPORT 2020 Table of Contents Board of Directors’ Report 3 Consolidated Income Statements 9 Consolidated Statements of Comprehensive Income 9 Consolidated Statements of Financial Position 10 Consolidated Statements of Changes in Equity 12 Consolidated Statements of Cash Flow 13 Notes to the Consolidated Financial Statements 14 The Parent Company’s Income Statements 43 The Parent Company’s Statements of Comprehensive Income 43 The Parent Company’s Balance Sheets 44 The Parent Company’s Statements of Changes in Equity 45 The Parent Company’s Statements of Cash Flow 45 Notes to the Parent Company’s Financial Statements 46 Auditor’s Report 56 Multi-year Summary 58 Translation from the Swedish original bonnier group ab annual report 2020 2 Board of Directors’ Report The Board of Directors and the CEO of Bonnier Group AB, corporate Development of the operations, financial position and registration no. 556576-7463, herewith submit the annual report profit or loss (Group) and consolidated financial statements for the 2020 financial year on pages 3-57. SEK million (unless stated otherwise) 2020 2019 Net sales 20,130 20,240 The Group’s business area and business model EBITA1) 945 -48 Bonnier Group AB is a parent company in a media group with Operating profit/loss 1,002 -140 companies in daily newspapers, business media, magazines, film Net financial items 1,096 -61 production, books, e-commerce and digital media and services. The Profit/loss before tax 2,098 -201 Group conducts operations in 12 countries with its base in the Nor- Profit/loss for the year 2,114 2,657 dic countries and operations in the United States, Germany, United EBITA margin 4.7% -0.2% Kingdom and Eastern Europe. -

The Signal and the Noise

nieman spring 2013 Vol. 67 no. 1 Nieman Reports The Nieman Foundation for Journalism REPOR Harvard University One Francis Avenue T s Cambridge, Massachusetts 02138 Nieman VOL Reports . 67 67 . To promoTe and elevaTe The sTandards of journalism n o. 1 spring 2013 o. T he signal and T he noise The SigNal aNd The NoiSe hall journalism and the future of crowdsourced reporting Carroll after the Boston marathon murdoch bombings ALSO IN THIS ISSUE Fallout for rupert mudoch from the U.K. tabloid scandal T HE Former U.s. poet laureate NIEMAN donald hall schools journalists FOUNDA Associated press executive editor T Kathleen Carroll on “having it all” ion a T HARVARD PLUS Murrey Marder’s watchdog legacy UNIVERSI Why political cartoonists pick fights Business journalism’s many metaphors TY conTEnts Residents and journalists gather around a police officer after the arrest of the Boston Marathon bombing suspect BIG IDEAS BIG CELEBRATION Please join us to celebrate 75 years of fellowship, share stories, and listen to big thinkers, including Robert Caro, Jill Lepore, Nicco Mele, and Joe Sexton, at the Nieman Foundation for Journalism’s 75th Anniversary Reunion Weekend SEPTEMBER 27–29 niEMan REPorts The Nieman FouNdatioN FoR Journalism at hARvARd UniversiTy voL. 67 No. 1 SPRiNg 2013 www.niemanreports.org PuBliShER Ann Marie Lipinski Copyright 2013 by the President and Fellows of harvard College. Please address all subscription correspondence to: one Francis Avenue, Cambridge, MA 02138-2098 EdiToR James geary Periodicals postage paid at and change of address information to: Boston, Massachusetts and additional entries. SEnioR EdiToR Jan gardner P.o. -

Tendances Mondiales En Matière De Liberté D'expression Et De

Publié en 2018 par l’Organisation des Nations Unies pour l’éducation, la science et la culture 7, place de Fontenoy, 75352 Paris 07 SP, France © UNESCO 2018 ISBN 978-92-3-200153-5 OEuvre publiée en libre accès sous la licence Attribution-ShareAlike 3.0 IGO (CC-BY-SA 3.0 IGO) (http://creativecommons. org/licenses/by-sa/3.0/igo/). Les utilisateurs du contenu de la présente publication acceptent les conditions d’utilisation de l’Archive ouverte en libre accès UNESCO (https://fr.unesco.org/open-access/les-licences-creative-commons). Ladite licence s’applique uniquement au texte contenu dans la publication. Pour l’usage de tout autre matériel qui ne serait pas clairement identifié comme appartenant à l’UNESCO, une demande d’autorisation préalable est nécessaire auprès de l’UNESCO : [email protected] ou Éditions l’UNESCO, 7, place de Fontenoy, 75352 Paris 07 SP France. Titre original : World Trends in Freedom of Expression and Media Development: 2017/2018 Global Report Publié en 2018 par l’Organisation des Nations Unies pour l’éducation, la science et la culture Davantage d’informations et le texte intégral du Rapport sur les tendances mondiales sont disponibles à l’adresse suivante : fr.unesco.org/world-media-trends-2017 L’étude complète doit être citée comme suit : UNESCO. 2018. Tendances mondiales en matière de liberté d’expression et de développement des médias : Rapport mondial 2017-2018, Paris. Les désignations employées dans cette publication et la présentation des données qui y figurent n’impliquent de la part de l’UNESCO aucune prise de position quant au statut juridique des pays, territoires, villes ou zones, ou de leurs autorités, ni quant au tracé de leurs frontières ou limites. -

FÖRINTELSENS RÖDA NEJLIKA Förintelsens Röda Nejlika Och Omvärlden, För Såväl Som Ny Äldre Viktig Forskning

Ulf Zander Raoul Wallenberg har fått status som en av andra världskrigets främsta FÖRINTELSENS RÖDA NEJLIKA hjältar tack vare de insatser han gjorde i Budapest 1944–1945 för att rädda judar undan Förintelsen. Samtidigt är hans öde förknippat med Raoul Wallenberg som historiekulturell symbol fångenskap och undergång i Sovjetunionen. I Förintelsens röda nejlika skriver Ulf Zander om den förändrade synen på Wallenberg i Sverige, Ungern och USA under efterkrigstiden. Diskussioner om det politiska och diplomatiska spelet kring honom är sammanflätat med olika kulturella gestaltningar av Wallenberg och hans öde. FÖRINTELSENS NEJLIKA RÖDA av Ulf Zander Ulf Zander är professor i historia med inriktning mot historiedidaktik vid Malmö högskola. Forum för levande historias skriftserie är en länk mellan forskarsamhället och omvärlden, för såväl ny som äldre viktig forskning. Syftet är att ge SKRIFT # 12:2012 spridning åt centrala forskningsresultat inom myndighetens kärnområden. Forum för levande historia FÖRINTELSENS RÖDA NEJLIKA Raoul Wallenberg som historiekulturell symbol av Ulf Zander SKRIFT # 12:2012 Forum för levande historia »Förintelsens röda nejlika – Raoul Wallenberg som historiekulturell symbol« ingår i Forum för levande historias skriftserie Författare Ulf Zander Redaktör Ingela Karlsson Ansvarig utgivare Eskil Franck Grafisk formgivning Ritator Omslagfoto Olivia Jeczmyk Foto Överst s. 186 Matti Östling Underst s. 186: Olivia Jeczmyk s. 127 och 132: Ulf Zander Övriga: Scanpix Tryck Edita, Västerås 2012 Forum för levande historia Box 2123, -

Universidad Complutense De Madrid Facultad De Ciencias De La Información

UNIVERSIDAD COMPLUTENSE DE MADRID FACULTAD DE CIENCIAS DE LA INFORMACIÓN TESIS DOCTORAL La promoción de la seguridad de los periodistas en perspectiva histórica: el papel de Naciones Unidas de 1945 a 2014 MEMORIA PARA OPTAR AL GRADO DE DOCTOR PRESENTADA POR Silvia Chocarro Marcesse Directores Concepción Anguita Olmedo Miguel Ángel Sobrino Blanco Madrid, 2016 © Silvia Chocarro Marcesse, 2016 UNIVERSIDAD COMPLUTENSE DE MADRID FACULTAD DE CIENCIAS DE LA INFORMACIÓN LA PROMOCIÓN DE LA SEGURIDAD DE LOS PERIODISTAS EN PERSPECTIVA HISTÓRICA: EL PAPEL DE NACIONES UNIDAS DE 1945 A 2014 Silvia Elena Chocarro Marcesse Directores: Concepción Anguita Olmedo Miguel Ángel Sobrino Blanco Madrid, 2015 II UNIVERSIDAD COMPLUTENSE DE MADRID FACULTAD DE CIENCIAS DE LA INFORMACIÓN Departamento de Sociología IV PROGRAMA DE DOCTORADO 276 “COMUNICACIÓN, CAMBIO SOCIAL Y DESARROLLO” LA PROMOCIÓN DE LA SEGURIDAD DE LOS PERIODISTAS EN PERSPECTIVA HISTÓRICA: EL PAPEL DE NACIONES UNIDAS DE 1945 A 2014 Silvia Elena Chocarro Marcesse Directores: Concepción Anguita Olmedo Miguel Ángel Sobrino Blanco Madrid, 2015 III IV Sabemos que el periodismo es clave para vencer el miedo que paraliza a una sociedad y para mantener viva la esperanza. Y no tenemos derecho a claudicar. No, al menos, mientras haya periodistas dando la batalla. Daniela Pastrana Periodistas de a pie, México Here is a calling that is yet above high office, fame, lucre and security. It is the call of conscience Lasantha Wickrematunge (asesinado el 9-11-09) Sunday Leader, Sri Lanka Premio Mundial de Libertad de Prensa UNESCO/Guillermo Cano V VI A George, A mis padres, A mi hermana, VII VIII AGRADECIMIENTOS Esta tesis se ha hecho realidad gracias, en primer lugar, a mis directores Concepción Anguita Olmedo y Miguel Ángel Sobrino Blanco. -

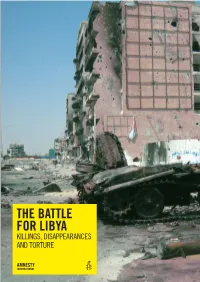

The Battle for Libya

THE BATTLE FOR LIBYA KILLINGS, DISAPPEARANCES AND TORTURE Amnesty International is a global movement of more than 3 million supporters, members and activists in more than 150 countries and territories who campaign to end grave abuses of human rights. Our vision is for every person to enjoy all the rights enshrined in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and other international human rights standards. We are independent of any government, political ideology, economic interest or religion and are funded mainly by our membership and public donations. First published in 2011 by Amnesty International Ltd Peter Benenson House 1 Easton Street London WC1X 0DW United Kingdom © Amnesty International 2011 Index: MDE 19/025/2011 English Original language: English Printed by Amnesty International, International Secretariat, United Kingdom All rights reserved. This publication is copyright, but may be reproduced by any method without fee for advocacy, campaigning and teaching purposes, but not for resale. The copyright holders request that all such use be registered with them for impact assessment purposes. For copying in any other circumstances, or for reuse in other publications, or for translation or adaptation, prior written permission must be obtained from the publishers, and a fee may be payable. To request permission, or for any other inquiries, please contact [email protected] Cover photo : Misratah, Libya, May 2011 © Amnesty International amnesty.org CONTENTS Abbreviations and glossary .............................................................................................5 Introduction .................................................................................................................7 1. From the “El-Fateh Revolution” to the “17 February Revolution”.................................13 2. International law and the situation in Libya ...............................................................23 3. Unlawful killings: From protests to armed conflict ......................................................34 4.