Libya | Freedom House

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

United Nations A/HRC/17/44

United Nations A/HRC/17/44 General Assembly Distr.: General 12 January 2012 Original: English Human Rights Council Seventeenth session Agenda item 4 Human rights situation that require the Council’s attention Report of the International Commission of Inquiry to investigate all alleged violations of international human rights law in the Libyan Arab Jamahiriya* Summary Pursuant to Human Rights Council resolution S-15/1 of 25 February 2011, entitled “Situation of human rights in the Libyan Arab Jamahiriya”, the President of the Human Rights Council established the International Commission of Inquiry, and appointed M. Cherif Bassiouni as the Chairperson of the Commission, and Asma Khader and Philippe Kirsch as the two other members. In paragraph 11 of resolution S-15/1, the Human Rights Council requested the Commission to investigate all alleged violations of international human rights law in the Libyan Arab Jamahiriya, to establish the facts and circumstances of such violations and of the crimes perpetrated and, where possible, to identify those responsible, to make recommendations, in particular, on accountability measures, all with a view to ensuring that those individuals responsible are held accountable. The Commission decided to consider actions by all parties that might have constituted human rights violations throughout Libya. It also considered violations committed before, during and after the demonstrations witnessed in a number of cities in the country in February 2011. In the light of the armed conflict that developed in late February 2011 in the Libyan Arab Jamahiriya and continued during the Commission‟s operations, the Commission looked into both violations of international human rights law and relevant provisions of international humanitarian law, the lex specialis that applies during armed conflict. -

Libya Conflict Insight | Feb 2018 | Vol

ABOUT THE REPORT The purpose of this report is to provide analysis and Libya Conflict recommendations to assist the African Union (AU), Regional Economic Communities (RECs), Member States and Development Partners in decision making and in the implementation of peace and security- related instruments. Insight CONTRIBUTORS Dr. Mesfin Gebremichael (Editor in Chief) Mr. Alagaw Ababu Kifle Ms. Alem Kidane Mr. Hervé Wendyam Ms. Mahlet Fitiwi Ms. Zaharau S. Shariff Situation analysis EDITING, DESIGN & LAYOUT Libya achieved independence from United Nations (UN) trusteeship in 1951 Michelle Mendi Muita (Editor) as an amalgamation of three former Ottoman provinces, Tripolitania, Mikias Yitbarek (Design & Layout) Cyrenaica and Fezzan under the rule of King Mohammed Idris. In 1969, King Idris was deposed in a coup staged by Colonel Muammar Gaddafi. He promptly abolished the monarchy, revoked the constitution, and © 2018 Institute for Peace and Security Studies, established the Libya Arab Republic. By 1977, the Republic was transformed Addis Ababa University. All rights reserved. into the leftist-leaning Great Socialist People's Libyan Arab Jamahiriya. In the 1970s and 1980s, Libya pursued a “deviant foreign policy”, epitomized February 2018 | Vol. 1 by its radical belligerence towards the West and its endorsement of anti- imperialism. In the late 1990s, Libya began to re-normalize its relations with the West, a development that gradually led to its rehabilitation from the CONTENTS status of a pariah, or a “rogue state.” As part of its rapprochement with the Situation analysis 1 West, Libya abandoned its nuclear weapons programme in 2003, resulting Causes of the conflict 2 in the lifting of UN sanctions. -

UNIVERSITY of CALIFORNIA, IRVINE the Arab Spring Abroad

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA, IRVINE The Arab Spring Abroad: Mobilization among Syrian, Libyan, and Yemeni Diasporas in the U.S. and Great Britain DISSERTATION Submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in Sociology by Dana M. Moss Dissertation Committee: Distinguished Professor David A. Snow, Chair Chancellor’s Professor Charles Ragin Professor Judith Stepan-Norris Professor David S. Meyer Associate Professor Yang Su 2016 © 2016 Dana M. Moss DEDICATION To my husband William Picard, an exceptional partner and a true activist; and to my wonderfully supportive and loving parents, Nancy Watts and John Moss. Thank you for everything, always. ii TABLE OF CONTENTS Page LIST OF ACRONYMS iv LIST OF FIGURES v LIST OF TABLES vi ACKNOWLEDGMENTS vii CURRICULUM VITAE viii ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION xiv INTRODUCTION 1 PART I: THE DYNAMICS OF DIASPORA MOVEMENT EMERGENCE CHAPTER 1: Diaspora Activism before the Arab Spring 30 CHAPTER 2: The Resurgence and Emergence of Transnational Diaspora Mobilization during the Arab Spring 70 PART II: THE ROLES OF THE DIASPORAS IN THE REVOLUTIONS 126 CHAPTER 3: The Libyan Case 132 CHAPTER 4: The Syrian Case 169 CHAPTER 5: The Yemeni Case 219 PART III: SHORT-TERM OUTCOMES OF THE ARAB SPRING CHAPTER 6: The Effects of Episodic Transnational Mobilization on Diaspora Politics 247 CHAPTER 7: Conclusion and Implications 270 REFERENCES 283 ENDNOTES 292 iii LIST OF ACRONYMS FSA Free Syria Army ISIS The Islamic State of Iraq and Al-Sham, or Daesh NFSL National Front for the Salvation -

A Typology of Conflict Dyads and Instruments of Power in Libya, 2014‐Present

Demystifying Gray Zone Conflict: A Typology of Conflict Dyads and Instruments of Power in Libya, 2014‐Present Report to DHS S&T Office of University Programs and DoD Strategic Multilayer Assessment Branch November 2016 National Consortium for the Study of Terrorism and Responses to Terrorism A Department of Homeland Security Science and Technology Center of Excellence Led by the University of Maryland 8400 Baltimore Ave., Suite 250 • College Park, MD 20742 • 301.405.6600 www.start.umd.edu National Consortium for the Study of Terrorism and Responses to Terrorism A Department of Homeland Security Science and Technology Center of Excellence About This Report The authors of this report are Rachel A. Gabriel, Researcher, and Mila A. Johns, Researcher, at the National Consortium for the Study of Terrorism and Responses to Terrorism (START). Questions about this report should be directed to Barnett S. Koven at [email protected]. This report is part of START project, “Shadows of Violence: Empirical Assessments of Treats, Coercion and Gray Zones,” led by Amy Pate. This research was supported by a Centers of Excellence Supplemental award from the Department of Homeland Security’s Science and Technology Directorate’s Office of University Programs, with funding provided by the Strategic Multilayer Assessment (SMA) Branch of the Department of Defense through grand award number 2012ST061CS0001‐05 made to the National Consortium for the Study of Terrorism and Responses to Terrorism (START). The views and conclusions contained in this document are those of the authors and should not be interpreted as necessarily representing the official policies, either expressed or implied, of the U.S. -

BACKGROUND GUIDE UNSC BBPS – Glengaze – MUN

BACKGROUND GUIDE UNSC BBPS – Glengaze – MUN Agenda – “Peace Building Measures in Post Conflict Regions with Special Emphasis on Iraq and Libya.” LETTER FROM THE EXECUTIVE BOARD Greetings, We welcome you to the United Nations Security Council, in the capacity of the members of the Executive Board of the said conference. Since this conference shall be a learning experience for all of you, it shall be for us as well. Our only objective shall be to make you all speak and participate in the discussion, and we pledge to give every effort for the same. How to research for the agenda and beyond? There are several things to consider. This background guide shall be different from the background guides you might have come across in other MUNs and will emphasise more on providing you the right Direction where you find matter for your research than to provide you matter itself, because we do not believe in spoon- feeding you, nor do we believe in leaving you to swim in the pond all by yourself. However, we promise that if you read the entire set of documents so provided, you shall be able to cover 70% of your research for the conference. The remaining amount of research depends on how much willing are you to put in your efforts and understand those articles and/or documents. So, in the purest of the language we can say, it is important to read anything and everything whose links are provided in the background guide. What to speak in the committee and in what manner? The basic emphasis of the committee shall not be on how much facts you read and present in the committee but how you explain them in simple and decent language to us and the fellow committee members. -

Intelligence Failures in Countering Islamic Terrorism: a Comparative Analysis on the Strategic Surprises of the 9/11 and the Pa

Department of Political Science Master’s Degree in International Relations - Global Studies Chair of Geopolitical Scenarios and Political Risk Intelligence Failures in Countering Islamic Terrorism: A Comparative Analysis on the Strategic Surprises of the 9/11 and the Paris Attacks and the Exceptionality of the Italian Case SUPERVISOR CANDIDATE Prof. Giuseppe Scognamiglio Antonella Camerino Student ID: 639472 CO-SUPERVISOR Prof. Lorenzo Castellani ACCADEMIC YEAR 2019-2020 TABLE OF CONTENTS ABSTRACT…………………………………………………………………………………………5 INTRODUCTION…………………………………………………………………………………..6 CHAPTER 1: Intelligence: A Theoretical Framework 1.1 – The Intelligence Cycle………………………………………………………………….11 1.2 – Intelligence Failures…………………………………………………………………….19 1.3 – The Strategic Surprises and Surprises Attacks………………………………………….24 1.4 – The Black Swan Theory………………………………………………………………...30 CHAPTER 2: The Case of USA: The Attacks of the 9/11 2.1 – The US Intelligence Community……………………………………………………….35 2.2 – Analysis of a Terrorist Organization: Al-Qaeda………………………………………..43 2.3 – The 9/11 Attacks: Facts, Causes and Consequences……………………………………52 2.4 – The US Involvement in the Middle East: The War on Terror………………………….61 CHAPTER 3: The Case of France: The Paris Attacks of November 13 3.1 – The French Intelligence Community…………………………………………………...73 3.2 – Analysis of a Terrorist Organization: The Islamic State………………………………..80 3.3 – The Paris Attacks of November 13: Facts, Causes and Consequences………………...90 3.4 – The French Involvement in the Middle East: Opération Chammal…………………….98 -

Freedom of the Press

Libya freedomhouse.org /report/freedom-press/2014/libya Freedom of the Press Status change explanation: Libya declined from Partly Free to Not Free due to the impact of the deteriorating security situation on journalists and other members of the press, who suffered a spate of threats, kidnappings, and attacks in 2013, often at the hands of nonstate actors. There was also an increased use of Qadhafi-era penal and civil codes to bring defamation cases against journalists, with one reporter facing up to 15 years in prison for alleging judicial corruption. Although the overthrow of longtime leader Mu’ammar al-Qadhafi led to a dramatic opening in the political and media environments in 2011, conditions for press freedom in Libya deteriorated in 2013. The new Libyan government—composed of the legislative assembly, or General National Congress (GNC), and a cabinet headed by Prime Minister Ali Zeidan—failed to establish security and the rule of law. Various semiautonomous militias, which control different parts of the country, continued to assert themselves, employing increasingly violent tactics and contributing to an unstable operating environment for journalists, especially in the restive eastern city of Benghazi. In September, after a long delay, the High National Election Commission announced that it would hold elections in early 2014 for the Constituent Assembly, the body tasked with drafting a permanent constitution. The governing legal document during 2013 remained the Draft Constitutional Charter for the Transitional Stage, adopted during the 2011 civil war, which guarantees several fundamental human rights. For example, Article 13 stipulates “freedom of opinion for individuals and groups, freedom of scientific research, freedom of communication, liberty of press, printing, publication and mass media.” While these provisions are a positive start, they do not fully reflect international standards for freedom of expression. -

The North African-Middle East Uprisings from Tunisia to Libya

HERBERT P. BIX The North African-Middle East Uprisings from Tunisia to Libya REVOLUTIONARY WAVE OF UPRISINGS has swept Over North A Africa and the Middle East, and the United States and its allies are struggHng to contain it. To place current US actions in Arab countries across the region in their proper context, a historical perspective, with events hned up chronologically, is useful. The US remains the global hegemon: it frames global debate and pos- sesses an unrivaled military machine. Few Arab rulers can remain unaf- fected by its policies. But far from being the sort of hegemon that can dominate through latent force, it must continually fight costly air and ground wars. The inconclusive character of these wars, and the decaying character of its domestic society and economy, reveals a weakened, over- extended power. Because of America's decade-long, unending wars and occupations massive numbers of MusHm civilians have died, while the productive sector of the US economy has steadily contracted. What foHows is a brief sketch, starting with how the European powers shaped the Middle East and North Africa until the United States displaced them, then jumping to the present in order to survey the authoritarian regimes in the non-Western societies of Tunisia, Egypt, Bahrain, Yemen, and Libya as they confront the rage of anti-regime forces. My central aim is to show that contemporary American-European interventions are best understood not as attempts to protect endangered civihans, as official US rhetoric holds, but as an extension of the logic of empire—continuous with the past and with the ethos of imperiahsm. -

The Kefaya Movement

THE ARTS This PDF document was made available CHILD POLICY from www.rand.org as a public service of CIVIL JUSTICE the RAND Corporation. EDUCATION ENERGY AND ENVIRONMENT Jump down to document6 HEALTH AND HEALTH CARE INTERNATIONAL AFFAIRS The RAND Corporation is a nonprofit NATIONAL SECURITY research organization providing POPULATION AND AGING PUBLIC SAFETY objective analysis and effective SCIENCE AND TECHNOLOGY solutions that address the challenges SUBSTANCE ABUSE facing the public and private sectors TERRORISM AND HOMELAND SECURITY around the world. TRANSPORTATION AND INFRASTRUCTURE Support RAND WORKFORCE AND WORKPLACE Purchase this document Browse Books & Publications Make a charitable contribution For More Information Visit RAND at www.rand.org Explore the RAND National Defense Research Institute View document details Limited Electronic Distribution Rights This document and trademark(s) contained herein are protected by law as indicated in a notice appearing later in this work. This electronic representation of RAND intellectual property is provided for non-commercial use only. Unauthorized posting of RAND PDFs to a non-RAND Web site is prohibited. RAND PDFs are protected under copyright law. Permission is required from RAND to reproduce, or reuse in another form, any of our research documents for commercial use. For information on reprint and linking permissions, please see RAND Permissions. This product is part of the RAND Corporation monograph series. RAND monographs present major research findings that address the challenges facing the public and private sectors. All RAND mono- graphs undergo rigorous peer review to ensure high standards for research quality and objectivity. The Kefaya Movement A Case Study of a Grassroots Reform Initiative Nadia Oweidat, Cheryl Benard, Dale Stahl, Walid Kildani, Edward O'Connell, Audra K. -

Egypt's Second January Uprising: Causes and Consequences of a Would-Be Revolution

The New Era of the Arab World Egypt’s Second January Uprising: Causes and Consequences of a Would-be Revolution andrea teti tion of ordinary people over the past decade or the Lecturer increased civil society and trade union activism since Keys Department of Politics and International Relations 2006 that were the result of this marginalisation. On University of Aberdeen 25 January, and even more significantly on Friday the 28th, Egyptians’ frustration and desire for change Gennaro Gervasio outweighed the fear the regime had ended up rely- Lecturer Department of Modern History, Politics and ing on, and a combination of popular pressure and 2011 International Relations regime factionalism resulted in Mubarak’s ouster. Macquarie University, Sydney The Egyptian revolution’s potential regional impact Med. should not be underestimated, as subsequent re- volts in Libya, Yemen, Bahrain, and latterly Syria During the first months of 2011, the Egyptian politi- show – not to mention significant protests in Mo- cal system was shaken by a veritable political earth- rocco, Algeria, Jordan, Saudi Arabia and the Pales- quake, as the almost 30-year rule of President Hosni tinian Occupied Territories. Protesters in Tunisia and 30 Mubarak was brought to an end by a popular upris- Egypt are now struggling to consolidate their gains. ing. Despite uncertainties regarding the country’s Others hope to emulate their success. While it is far future – whether a fully democratic system will be from clear what enduring changes these uprisings implemented or whether the army will retain a “spe- herald, some important lessons on the roots and sig- cial” role within the polity – it is impossible to over- nificance of Egypt’s revolution can already be drawn. -

PAMUN XVI RESEARCH REPORT— Countering the Aftermath of the Arab Spring in Libya Introduction of Topic Background Information

PAMUN XVI RESEARCH REPORT— Countering the aftermath of the Arab Spring in Libya Introduction of Topic “Liberty, Justice, Democracy” – the words of the Libyan motto. However, after the Arab Spring, chaos has descended over the country, with armed groups out of control and critical human rights abuse. The Arab Spring was an anti-government revolution which took place from 17th December 2010 – mid 2012. It began with a wave of protests, riots and civil wars occurring in Tunisia with the Jasmine Revolution. The causes of this revolution were the alarming rate of government corruption causing distressing levels of inflation and below inadequate living conditions. Further issues were vast differences in income, social inequality, multiple human right violations and kleptocracy. The primary cause of the Arab Spring was authoritarianism in countries such as Syria, Libya, Yemen, Egypt, Iraq, Algeria, Kuwait, Morocco, Saudi Arabia and of course, Tunisia. This dictatorial behaviour led to large political riots, civil disobedience, internet activism, insurgency and other forms of protest. Citizens filled streets demanding democracy, free and fair elections along with economic freedom and the abolishment of corruption. During the Arab Spring, the Libyan Civil War broke out for 8 months in February 2011 after rulers were overturned in Egypt and Tunisia. It began with peaceful protests and soon escalated into an armed conflict between the government forces of Colonel Gaddafi and the rebels against his government. Background Information The Libyan Crisis refers to continuing civil war taking place as a result of the Arab Spring in Libya. The Crisis can be thought of as being in three parts: the first civil war which began and ended 2011, the inter-civil war atrocities which occurred due to the aftermath of the first war and the second civil war, which started early 2014 and is still presently ongoing. -

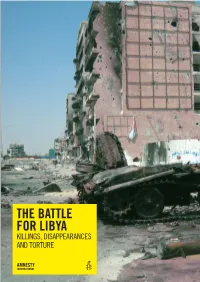

The Battle for Libya

THE BATTLE FOR LIBYA KILLINGS, DISAPPEARANCES AND TORTURE Amnesty International is a global movement of more than 3 million supporters, members and activists in more than 150 countries and territories who campaign to end grave abuses of human rights. Our vision is for every person to enjoy all the rights enshrined in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and other international human rights standards. We are independent of any government, political ideology, economic interest or religion and are funded mainly by our membership and public donations. First published in 2011 by Amnesty International Ltd Peter Benenson House 1 Easton Street London WC1X 0DW United Kingdom © Amnesty International 2011 Index: MDE 19/025/2011 English Original language: English Printed by Amnesty International, International Secretariat, United Kingdom All rights reserved. This publication is copyright, but may be reproduced by any method without fee for advocacy, campaigning and teaching purposes, but not for resale. The copyright holders request that all such use be registered with them for impact assessment purposes. For copying in any other circumstances, or for reuse in other publications, or for translation or adaptation, prior written permission must be obtained from the publishers, and a fee may be payable. To request permission, or for any other inquiries, please contact [email protected] Cover photo : Misratah, Libya, May 2011 © Amnesty International amnesty.org CONTENTS Abbreviations and glossary .............................................................................................5 Introduction .................................................................................................................7 1. From the “El-Fateh Revolution” to the “17 February Revolution”.................................13 2. International law and the situation in Libya ...............................................................23 3. Unlawful killings: From protests to armed conflict ......................................................34 4.