GENDER ASSESSMENT January 2020

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Living Through Nigeria's Six-Year

“When We Can’t See the Enemy, Civilians Become the Enemy” Living Through Nigeria’s Six-Year Insurgency About the Report This report explores the experiences of civilians and armed actors living through the conflict in northeastern Nigeria. The ultimate goal is to better understand the gaps in protection from all sides, how civilians perceive security actors, and what communities expect from those who are supposed to protect them from harm. With this understanding, we analyze the structural impediments to protecting civilians, and propose practical—and locally informed—solutions to improve civilian protection and response to the harm caused by all armed actors in this conflict. About Center for Civilians in Conflict Center for Civilians in Conflict (CIVIC) works to improve protection for civil- ians caught in conflicts around the world. We call on and advise international organizations, governments, militaries, and armed non-state actors to adopt and implement policies to prevent civilian harm. When civilians are harmed we advocate the provision of amends and post-harm assistance. We bring the voices of civilians themselves to those making decisions affecting their lives. The organization was founded as Campaign for Innocent Victims in Conflict in 2003 by Marla Ruzicka, a courageous humanitarian killed by a suicide bomber in 2005 while advocating for Iraqi families. T +1 202 558 6958 E [email protected] www.civiliansinconflict.org © 2015 Center for Civilians in Conflict “When We Can’t See the Enemy, Civilians Become the Enemy” Living Through Nigeria’s Six-Year Insurgency This report was authored by Kyle Dietrich, Senior Program Manager for Africa and Peacekeeping at CIVIC. -

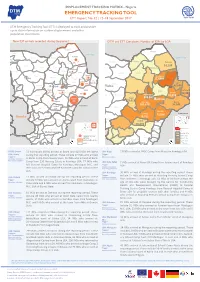

ETT Report-No.32.V2

DISPLACEMENT TRACKING MATRIX - Nigeria DTM Nigeria EMERGENCY TRACKING TOOL ETT Report: No. 32 | 12–18 September 2017 IOM OIM DTM Emergency Tracking Tool (ETT) is deployed to track and provide up-to-date information on sudden displacement and other population movements New IDP arrivals recorded during the period DTM and ETT Cumulative Number of IDPs by LGA Abadam Abadam Yusufari Lake Chad Kukawa Yusufari Yunusari Mobbar Lake Chad± Nguru Karasuwa Niger Machina Yunusari Mobbar Abadam Kukawa Lake Chad Bade Guzamala 79 Nguru Karasuwa Kukawa Bursari 14,105 Geidam Gubio Bade Bade Guzamala Monguno Mobbar Nganzai Jakusko Bursari 6240 Marte Geidam Gubio Bade Guzamala Ngala Tarmua Monguno Magumeri Nganzai Jakusko Yobe 122,844 Marte 43 Gubio Monguno Jere Dikwa 7 Mafa Kala/BalgeYobe Ngala Maiduguri M.C. 122 Tarmua Nganzai Nangere Fune Damaturu Jigawa Magumeri 42,686 Borno 18 Yobe Marte Potiskum Ngala Kaga Konduga Bama Jere Mafa Kala/Balge Magumeri Dikwa 17 30 73 Yobe 49,480 Fika Gujba Nangere Fune Damaturu Maiduguri Mafa 74,858 Jere Dikwa Gwoza Potiskum Kaga Borno308,807 Kala-Balge MaiduBornoguri Damboa 799 19,619 KondugaKonduga Bama Gulani Cameroon Kag1a05,678 56,748 Chibok Konduga Fika Gujba Bama Biu 11 Madagali Askira/Uba Gwoza Michika Damboa Cameroon Kwaya Kusar 73,966Gwoza Hawul Damboa Bauchi Gombe Bayo Mubi North 76,795 Hong Gulani Shani Chibok Gombi Mubi South Madagali Biu Biu 16,378Chibok Maiha Askira/Uba Askira-Uba Inaccessible area Guyuk Song Michika Shelleng IDP severity Kwaya KusarKwaya Kusar Hawul Adamawa Hawul Less t han 10,788 Bauchi Gombe Bayo Mubi North Lamurde Number of new Bayo 10,788 - 25,813 HongAdamawa Numan Girei arrivals Shani Cameroon 25,813 - 56,749 Demsa Inaccessible area Shani Gombi Mubi South Yola South 56,749 - 122,770 Yola North Gombe 0 15 30 60 Km 122,770 Above Fufore LGAChad Adamawa Plateau Mayo-Belwa Shelleng Maiha Guyuk Song STATE: Borno 73 individuals (INDs) arrived at Bama and 129 INDs le� Bama LGA: Kaga 17 INDs arrived at NYSC Camp from Musari in Konduga LGA. -

Yobe State Multisectoral Crisis Recovery Project (Mcrp)

YOBE STATE MULTISECTORAL CRISIS RECOVERY PROJECT (MCRP) Environmental & Social Impact Assessment (ESIA) For Rehabilitation of 40km Gujba-Ngalda Road INFRASTRUCTURE PROJECTS UNDER COMPONENT 2 OF MCRP DRAFT REPORT MARCH, 2020 Yobe MCRP – Environmental & Social Impact Assessment (ESIA) for 40km Gujba-Ngalda Road Table of Contents List of Figures .................................................................................................. v List of Tables .................................................................................................. vi Acronyms and Abbreviations ............................................................................ vii Executive Summary ......................................................................................... ix CHAPTER ONE: INTRODUCTION ......................................................................... 2 1.1 Background ........................................................................................ 2 1.1.1 Technical Approach and Methodology to the ESIA ................................. 3 1.1.2 Desktop Research ......................................................................... 3 1.1.3 Reconnaissance Survey and Field Visits ........................................... 3 1.2 Applicable Laws and International Regulatory Framework ........................ 4 1.3 International Treaties and Conventions on Environment ........................... 6 1.5 Gender-Based Violence ........................................................................ 7 1.5.1 International -

Impacts of Boko Haram Insurgency on Agricultural Activities in Gujba Local Government Area, Yobe State, Nigeria

Research Publisher: Manuscript central Available Online at www.ijcrr.info International Journal of Contemporary Research and Review ISSN 0976 – 4852 https://doi.org/10.15520/ijcrr.v9i12.628 December, 2018|Volume 09|Issue 12| Section: Agriculture Impacts of Boko Haram Insurgency on Agricultural Activities in Gujba Local Government Area, Yobe State, Nigeria. M. Babagana1, M. Ismail2, B. G. Mohammed3, M. A. Dilala4, Hussaini I5, I M. Zangoma6 1Department of Animal Health and Production Technology College of Agriculture Gujba Yobe State, Nigeria 2Department of Agricultural Technology College of Agriculture Gujba Yobe State, Nigeria 3Department of Agricultural Technology College of Agriculture Gujba Yobe State, Nigeria 4Department of Animal Health and Production Technology College of Agriculture Gujba Yobe State, Nigeria 5Department of Agricultural Technology College of Agriculture Gujba Yobe State, Nigeria 6Department of Agricultural Technology College of Agriculture Gujba Yobe State, Nigeria Corresponding Author: M. Babagana Received: 2018-11-14; Accepted 2018-12-06, Abstract: The study was conducted between the months of November-December 2018 to assess the impacts of Boko Haram insurgency on agricultural activities in Gujba Local Government Area of Yobe state, Nigeria. Six towns namely Buni Yadi, Gujba, Goniri, Katarko, Mutai and Wagir formed the study locations. These towns were the major agricultural strongholds of the Local Government. The study considered impacts of the insurgency on farming after the return of residents to these towns after almost two years of exile in other places as a result of displacement by the militants’ activities (2016-2018). Descriptive Survey design involving mixed methods was used in which a total of 394 respondents participated. -

YOBE STATE MINISTRY of HEALTH Situation Report

YOBE STATE MINISTRY OF HEALTH Situation Report TITLE COVID-19 Pandemic Situation Report SERIAL NUMBER 17 EPID-WEEK 20 DATE 16 May 2020 HIGHLIGHTS: No new confirmed case(s) reported today Fifty-one (51) new contacts of the confirmed cases have been identified and line-listed by the contact tracing teams SMOH and WHO recruited, trained and deployed six (6) additional contact tracing teams in Gujba, Nguru, and Tarmuwa LGAs Seven (7) new alerts have been received and investigated in Nguru, Potiskum and Gujba LGAs Conducted high-level advocacy, led by the Hon Commissioner for Health (Vice-Chairman of State Task Force) and other members of State Rapid Response Team (SRRT), to Bade LGA emirate council to sensitize traditional leaders and community members on prevention of COVID-19 in their communities. EPIDEMIOLOGICAL SUMMARY: The total number of confirmed COVID-19 cases remains thirty-two (32): Sixteen (16) cases from Damaturu, eight (8) cases from Bade, five (5) cases from Nguru, and one (1) case each from Geidam, Tarmuwa, and Gujba LGAs Total confirmed cases of COVID-19 amongst Health Care Workers (HCWs) in the state remain nine (9): Six (6) nurses, two (2) doctors, and one (1) laboratory scientist Twenty-four (24) confirmed cases are on admission in isolation centers. All are in stable condition Three (3) cases have recovered and discharged from the isolation center two days ago The total number of contacts who completed the 14-days follow-up as of today is one hundred and twenty-four (124). None of them developed any symptoms The total number of deaths due to COVID-19 in the state is five (5) The total number of samples taken for testing remains sixty-three (63). -

Through Our Eyes People's Perspectives on Building Peace In

Policy paper April 2018 Through our eyes People’s perspectives on building peace in northeast Nigeria Key findings 1. Communities excluded from decision-making: 4. Proliferation of wider divisions in society: Local populations feel excluded from national The Boko Haram insurgency has led to wider and international responses to the Boko divisions within society that threaten the Haram insurgency. They feel their fears, needs long-term prospects for peace and reconciliation and concerns are not properly considered. in the region. The insurgency has created Communities resent this lack of engagement or exacerbated tensions between different and feel it leads to ineffective and inappropriate religious and ethnic groups, between Internally programming that is failing to reach the most Displaced People (IDPs) and host communities, vulnerable sections of society, and in some and between returning IDPs and members of cases is making the situation worse. their community who did not flee. 2. Dialogue with Boko Haram as part of a peace 5. Public mistrust of government and security strategy: The majority of people recognise that actors: Despite an improvement in relations a military approach alone will not bring peace to between civilians and government and security the region and support engagement in dialogue institutions since the early years of the insurgency, with Boko Haram as part of a multifaceted the relationship is still characterised by high approach to peace. levels of mistrust, fear and suspicion. 3. The risks of ‘imposed’ reintegration: 6. Concern about the future role of vigilante groups: Local populations feel that it is too soon While local populations are appreciative of the for people associated with Boko Haram to role that vigilante groups – including the Civilian be reintegrated into communities and that Joint Task Force – have played in improving the reintegration is being ‘imposed’, ignoring their security situation, they are fearful that vigilante fears and concerns. -

Partner Presence in Borno State

Partner Presence in Borno State - North East Nigeria Partner Presence and Number of Beneficiaries Assisted at LGA level | December 2019 SO1 - FOOD ASSISTANCE SO2 - AGRICULTURE & LIVELIHOODS LEGEND LEGEND State Boundary State Boundary LGA Boundary LGA Boundary Hard to reach LGA Hard to reach LGA ASKIRA/UBA–60,525 7 Individuals Assisted Individuals Assisted FAO, NRC, PI, CARITAS*, No Data FREE*, UNDP, CSCED* No Data < 5,000 < 5,000 BAMA – 45,520 9 5001 – 50,000 5001 – 50,000 BOSADP*, FAO, 50,001 – 100,000 GREENCODE, DHCBI*, 50,001 – 100,000 UNDP, MCRP, HOPE, 100,001 – 200,000 WFP, INTERSOS* 100,001 – 200,000 > 300,000 BAYO – 1400 2 BAMA – 166,691 5 > 300,000 WFP, DRC*, CARITAS, JDPC INTERSOS*, MC,SEMA BIU – 75,686 11 DAMBOA – 97,325 3 IDS, VSF, CARITAS, WFP, IMC*, MC JDPC, FAO, BOSADP*, NRC, UNDP, MC, IITA*, ICRISAT* DIKWA – 35,162 3 CHIBOK – 38,419 5 WFP, CARE*, CAID* IDS, FAO, BOSADP*, CARITAS*, VSF GUBIO – 10,819 2 DAMBOA – 48,251 7 CRS, NEYIF FAO, ADRA*, NRC, MAGUMERI – 68,740 5 UNDP, MC, WFP, 4 GWOZA – 62,464 DHCBI* AAH, WFP, CRS, JDPC, MAIDUGURI – 27,413 9 WFP, PI*, CARE* INTERSOS* DIKWA – 109,324 9 FAO, DHCBI*, NEMA, LHI*, NCFRMI, SEMA, JERE – 197,086 5 MAIDUGURI– 122,841 7 FAO, BOSADP*, WFP, WFP, CAID*, NRCS, CARE*, CAID*, CRUDAN, AAH, SC, EYN, ZOA, JDPH TEARFUND, MC, DHCBI* NEMA AAH, SCI, EYN, WFP, IMC*, PUI, NEMA MOBBAR – 56,529 4 KAGA– 14,764 2 GUBIO – 30,809 4 AAH, MCRP, HOPE, NRC JERE – 203,342 19 MOBBAR – 29,000 2 AAH, CRS, FAO, NEYIF* CRS, JDPC ActionAid, HLI, FAO, KWAYA KUSAR–6,545 3 MONGUNO –262,660 15 WFP,INTERSOS* BOSADP*, -

African Programme for Oiichocerciasis Control (Apoc)

AFRICAN PROGRAMME FOR OIICHOCERCIASIS CONTROL (APOC) Year 2 Report for Community Directed rreatment with Ivermectin CDTI Yusufari Yunusari Nguru Bade Bursari Geidam Jakusko Tarmuwa Fune aturu Gujba Gulani Yobe State Nigeria December 2000 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY. Yobe State was created out of the formerBorno State inAugust 1991. It is situated in the North Eastern part of the country in Sahel Savannah and desert features in the northern part of the State charactenze its topogaphy while the southem part has rocky hills and mountainous terrain with rivers giving it the identity of the Sudan Savannah. The river Yobe is of particular mention as it cuts across Six (6) LGAs, and it serve as breeding sites of the black flies. The State covers an estimated landmass of 47,153 sq. kilometers, with a population of 1.4 million people. Yobe State has a total of Seventeen (17) Local Government Councils. Twelve (12) of which are Meso-endemic with few southern areas having hyper-endemic communities, especially in those belts that run across the Biu LGA of Borno State. The people of the state are mostly involved in farming, cattle rearing, fishing etc. Treatment started in the state in the year 1995, after CBM signed a Memorandum of Understanding to assist in the control effort. Over trvo hundred thousand persons have been treated since then. The State wrote a proposal to APOC for possible assistance in the year 1997 to implement CDTI, and this was approved for funding in September 1998. The state is currently in its second year of CDTI implementation, with all emphasis shifted to community ownership of the prograrnme. -

April – June 2020

Nigeria: Yobe - Health Sector Reporting Partners (April - June, 2020) Number of Local Reporting PARTNERS PER TYPE OF ORGANIZATIONS BREAKDOWN OF PEOPLE REACHED PER CATEGORY Government Area Partners NGOs/UN People Reached PiN/Target IDP Returnee Host 08 Agencies Community 17 Partners including 204,102 LGAs with ongoing International NGOs and activities 87,507 10,531 165 76,811 UN Agencies 4/4 151,047 KARASUWA (1 Partner) YUSUFARI (2 Partners) YUNUSARI (1 Partner) WHO PLAN, WHO WHO REACHED: 713 REACHED: 1,558 REACHED: 3,377 MACHINA (1 Partner) YUSUFARI GEIDAM (1 Partner) WHO YUNUSARI WHO NGURU REACHED: 1,068 MACHINA REACHED: 6,539 KARASUWA BADE BURSARI (2 Partners) NGURU (2 Partners) BURSARI PLAN, WHO PLAN, WHO BADE GEIDAM REACHED: 2,458 REACHED: 1,715 JAKUSKO TARMUA (2 Partners) BADE (1 Partner) TARMUA WHO AAH, WHO REACHED: 6,625 REACHED: 1,092 DAMATURU NANGERE DAMATURU (5 Partners) JAKUSKO (1 Partner) POTISKUM IRC, PLAN, UNFPA, UNICEF, WHO WHO FUNE REACHED: 9,705 REACHED: 1,815 FIKA GUJBA GUJBA (5 Partners) NANGERE (2 Partners) AAH, IOM, IRC, UNICEF, WHO AAH, WHO GULANI Number of Organizations REACHED: 24,292 REACHED: 5,525 0 5 GULANI (3 Partners)P POTISKUM (2 Partners) IOM, UNICEF, WHO RHHF, UNFPA REACHED: 17,229 REACHED: 23 FIKA (1 Partner) FUNE (2 Partners) .WHO PLAN, WHO REACHED: 2,769 REACHED: 1,105 ORGANIZATION ACRONYMS AAH Action Against Hunger YOBE Reached Benificiaries by Age CRS Catholic Relief Services Number of Individuals Displaced FHI 360 Family Health International by Insurgency 127,613 24,000 IFRC International Federation of Red Cross 20,000 IRC International Rescue Commitee 16,000 Estimated Number of IDPs 12,000 MSF - Spain Medecin Sans Frontieres Spain 133,183 8,000 UNFPA United Nations Population Fund 4,000 UNICEF United Nations Children's Education Fund Girls Boys Girls Boys Girls Boys Women Men Women Men Children (Under 1 years) Children (1 - 5 years) Children (6 - 17 years) Adults (18 - 59 years) Elderly (60+ years) WHO World Health Organization * DTM baseline assessment round XXXI OUR PARTNERS. -

Artboard 1Yobe State COVID-19 Risk

Nigeria: Yobe State - COVID-19 Risk Map for LGAs Number of Local Partners Government Area Presence NGOs/UN 17 14 Agencies LGAs with ongoing Partners including activities International NGOs, National NGOs and UN Agencies 11/3 KARASUWA (4 Partners) YUSUFARI (4 Partners) YUNUSARI (4 Partners) CRS, UNFPA, UNICEF, WHO CRS, UNFPA, UNICEF, WHO MSF-Spain, UNFPA, UNICEF, WHO MACHINA (4 Partners) YUSUFARI GEIDAM (4 Partners) CRS, UNFPA, UNICEF, WHO YUNUSARI MACHINA CRS, UNFPA, UNICEF,WHO NGURU KARASUWA BADE BURSARI (5 Partners) NGURU (6 Partners) BURSARI CRS, FHI360, IHVN, UNFPA, CRS, FHI360, GESDI, UNFPA, BADE GEIDAM UNICEF, WHO UNICEF, WHO JAKUSKO TARMUA (5 Partners) BADE (6 Partners) TARMUA GESDI, NEYIF, UNFPA, AAH, FHI360, GESDI, UNFPA, UNICEF, WHO UNICEF, WHO DAMATURU NANGERE DAMATURU (8 Partners) JAKUSKO (4 Partners) POTISKUM FHI360, IHVN, IRC, MC, NRC, COOPI, UNFPA, UNICEF, MSF-Spain, UNFPA, UNICEF, WHO FUNE WHO FIKA GUJBA GUJBA (8 Partners) NANGERE (3 Partners) AAH, ICRC, IRC, NRC/IFRC, UNFPA, UNICEF, WHO GULANI MC, UNFPA, UNICEF, WHO GULANI (8 Partners) POTISKUM (5 Partners) AAH, ICRC, IRC, NRC/IFRC, AAH, FHI360, UNFPA, MC, UNFPA, UNICEF, WHO UNICEF, WHO FIKA (5 Partners) FUNE (5 Partners) FHI360, GESDI, UNFPA, . CRS, NRC/IFRC, UNFPA, UNICEF, WHO UNICEF, WHO ORGANIZATION ACRONYMS IHVN Institute of Human Virology of Nigeria COVID-19: Risk Level AAH Action Against Hunger IRC International Rescue Commitee COOPI COOperazione Internationale MC Malaria Consortium Medium Risk CRS Catholic Relief Services MSF - Spain Medecin Sans Frontieres Spain High Risk FHI 360 Family Health International NEYIF North East Youth Initiative For Development L NRCS Nigerian Red Cross Society Very High Risk GESDI Green Environmental Sustainability & Development Initiative UNFPA United Nations Population Fund ICRC International Committee of the Red Cross UNICEF United Nations Children's Emergency Fund IFRC International Federation of Red Cross & WHO World Health Organization Red Crescent Societies OUR PARTNERS. -

MC Short Report

BUILDING RESILIENCE IN COMPLEX CRISIS(BRICC) BASELINE REPORT MARCH 2020 Funded by the European Union Table of Contents PROGRAM BACKGROUND ................................................................................................................. 3 Executive Summary 3 Research Methods 4 Research design and Rationale 4 Multi Phase Baseline Assessment 4 Research Approach 5 Study Population 5 Sampling Inclusion and Exclusion 6 Research tool, Techniques and Language 6 Participants Recruitment 7 Data Management, Analysis and Reporting 7 Presentation of Key findings 7 Conclusion 22 BRICC Logframe 28 BRICC Consortium Baseline Report 2 Funded by the European Union Program Background The European Union’s (EU) funded Building Resilience In Complex Crisis (BRICC) programme seek to build the absorptive and adaptive capacities of 26,875 households in Yobe state to be resilient to the shock and stresses of conflict, market disruptions, climate change and complex crisis. The programme will also transform the underlying casual dynamics to reduce the risks of future conflict by engaging communities and local leadership to create conditions to facilitate systemic change. Mercy Corps is leveraging its expertise in fostering resilience in complex environments both globally and in Northeast Nigeria, with its partners Cooperazione Internationale (COOPI) and the Danish Refugee Council (DRC)’s whose strong track record of relief and early recovery programs in Yobe state, will enable the consortium to rapidly start up and implement the BRICC program. BRICC’s ToC is IF communities most affected by conflict in Yobe state have improved social protection delivered through responsive, capable government, access to essential basic services and improved livelihood supported by robust markets, and IF key community leaders and government institutions manage resources, services and conflict peacefully and equitably while addressing drivers of participation of violence, THEN communities will achieve increasing well-being over time and experience the impacts of conflict less severely. -

YOBE STATE MINISTRY of HEALTH Situation Report

YOBE STATE MINISTRY OF HEALTH Situation Report TITLE COVID-19 Pandemic Situation Report SERIAL NUMBER 20 EPID-WEEK 21 DATE 19 May 2020 HIGHLIGHTS: ñ No new confirmed case(s) reported today ñ Twenty-two (22) contacts of the newly confirmed cases have been identified and line-listed by the contact tracing teams in Damaturu, Gujba, and Nguru LGAs ñ Twenty-eight (28) new samples have been collected and transported to NCDC-accredited laboratory for testing ñ Five (5) new alerts have been received and investigated in Damaturu, Nguru, and Bade LGAs. EPIDEMIOLOGICAL SUMMARY: ñ The total number of confirmed COVID-19 case(s) is thirty-four (34): Sixteen (16) cases from Damaturu, eight (8) cases from Bade, seven (7) cases from Nguru, and one (1) case each from Geidam, Tarmuwa, and Gujba LGAs ñ Total confirmed case(s) of COVID-19 amongst Health Care Workers (HCWs) in the state is eleven (11): Seven (7) nurses, three (3) doctors, and one (1) laboratory scientist ñ The total number of deaths due to COVID-19 in the state is six (6) ñ Total number of case(s) who recovered and discharged from the isolation center in the state is six (6) ñ The total number of contacts who completed the 14-days follow-up without any symptoms as of today is one hundred and thirty-two (132) ñ Twenty-two (22) confirmed cases in the isolation center are in stable condition ñ The total number of samples taken for testing is ninety-one (91). Of these, thirty-four (34) returned positive, twenty-two results (22) are negative and the results of thirty-five (35) remaining samples are being awaited.