Living Through Nigeria's Six-Year

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sambisa Final Draftnh

Total Aerial Count of Elephants and other Wildlife Species in Sambisa Game Reserve in Borno State, Nigeria By P. Omondi1, R. Mayienda2, Mamza, J.S.3, M.S. Massalatchi4 All correspondences E-mail: [email protected] JULY 2006 Table of Contents EXECUTIVE SUMMARY................................................................................................................................................ 4 INTRODUCTION .............................................................................................................................................................. 5 OBJECTIVES OF THE SURVEY .................................................................................................................................. 6 STUDY AREA..................................................................................................................................................................... 7 CLIMATE ........................................................................................................................................................................... 7 SOIL................................................................................................................................................................................... 8 FLORA & FAUNA .............................................................................................................................................................. 8 METHODOLOGY ............................................................................................................................................................ -

BOKO HARAM Emerging Threat to the U.S

112TH CONGRESS COMMITTEE " COMMITTEE PRINT ! 1st Session PRINT 112–B BOKO HARAM Emerging Threat to the U.S. Homeland SUBCOMMITTEE ON COUNTERTERRORISM AND INTELLIGENCE COMMITTEE ON HOMELAND SECURITY HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES December 2011 FIRST SESSION U.S. GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE 71–725 PDF WASHINGTON : 2011 COMMITTEE ON HOMELAND SECURITY PETER T. KING, New York, Chairman LAMAR SMITH, Texas BENNIE G. THOMPSON, Mississippi DANIEL E. LUNGREN, California LORETTA SANCHEZ, California MIKE ROGERS, Alabama SHEILA JACKSON LEE, Texas MICHAEL T. MCCAUL, Texas HENRY CUELLAR, Texas GUS M. BILIRAKIS, Florida YVETTE D. CLARKE, New York PAUL C. BROUN, Georgia LAURA RICHARDSON, California CANDICE S. MILLER, Michigan DANNY K. DAVIS, Illinois TIM WALBERG, Michigan BRIAN HIGGINS, New York CHIP CRAVAACK, Minnesota JACKIE SPEIER, California JOE WALSH, Illinois CEDRIC L. RICHMOND, Louisiana PATRICK MEEHAN, Pennsylvania HANSEN CLARKE, Michigan BEN QUAYLE, Arizona WILLIAM R. KEATING, Massachusetts SCOTT RIGELL, Virginia KATHLEEN C. HOCHUL, New York BILLY LONG, Missouri VACANCY JEFF DUNCAN, South Carolina TOM MARINO, Pennsylvania BLAKE FARENTHOLD, Texas MO BROOKS, Alabama MICHAEL J. RUSSELL, Staff Director & Chief Counsel KERRY ANN WATKINS, Senior Policy Director MICHAEL S. TWINCHEK, Chief Clerk I. LANIER AVANT, Minority Staff Director (II) C O N T E N T S BOKO HARAM EMERGING THREAT TO THE U.S. HOMELAND I. Introduction .......................................................................................................... 1 II. Findings .............................................................................................................. -

The Police and Criminal Justice System in Africa: Agenda for Reform

THE POLICE AND CRIMINAL JUSTICE SYSTEM IN AFRICA: AGENDA FOR REFORM Eme, Okechukwu I. and Okoh, Chukwuma I. Department of Public Administration, University of Nigeria, Nsukka. And Okeke,Martin Federal Polytechnic, Oko. Email: [email protected] Abstract Across much of the continent, cases of abuse by the police and security agencies are rampant. Indeed, protection of the populace by the police with no strings attached is often the aberration rather than the norm. Stories of police inefficiency, corruption and extortion of citizens abound. Recent political developments in Kenya, Zimbabwe and Nigeria, once again, brought to the fore the contentious issue of public protection on the continent. The clash between expectation and reality is one of the major issues at the heart of policing on the continent. Typically, emerging calls to the police either go unanswered or when answered, police lack the capacity for rapid response thus arriving at the crime scene too late or not at all. It is not uncommon for personal callers to police stations to pay bribes before being served. No wonder many citizens seek protection from alternative sources including private security, civil militia and vigilante groups as seen in many parts of Nigeria, South Africa, Kenya and Liberia among others. The paper seeks to examine various theoretical and practical problems of the police as a significant element in the criminal justice system in Africa. The paper will equally use the post-colonial state framework of analysis to capture the thesis that the criminal justice system in any society reflects the socio-economic system in operation. The paper will highlight the challenges facing the police in Africa and suggests ways of correcting them. -

POLICING REFORM in AFRICA Moving Towards a Rights-Based Approach in a Climate of Terrorism, Insurgency and Serious Violent Crime

POLICING REFORM IN AFRICA Moving towards a rights-based approach in a climate of terrorism, insurgency and serious violent crime Edited by Etannibi E.O. Alemika, Mutuma Ruteere & Simon Howell POLICING REFORM IN AFRICA Moving towards a rights-based approach in a climate of terrorism, insurgency and serious violent crime Edited by Etannibi E.O. Alemika, University of Jos, Nigeria Mutuma Ruteere, UN Special Rapporteur, Kenya Simon Howell, APCOF, South Africa Acknowledgements This publication is funded by the Ford Foundation, the United Nations Development Programme, and the Open Societies Foundation. The findings and conclusions do not necessarily reflect their positions or policies. Published by African Policing Civilian Oversight Forum (APCOF) Copyright © APCOF, April 2018 ISBN 978-1-928332-33-6 African Policing Civilian Oversight Forum (APCOF) Building 23b, Suite 16 The Waverley Business Park Wyecroft Road Mowbray, 7925 Cape Town, ZA Tel: +27 21 447 2415 Fax: +27 21 447 1691 Email: [email protected] Web: www.apcof.org.za Cover photo taken in Nyeri, Kenya © George Mulala/PictureNET Africa Contents Foreword iv About the editors v SECTION 1: OVERVIEW Chapter 1: Imperatives of and tensions within rights-based policing 3 Etannibi E. O. Alemika Chapter 2: The constraints of rights-based policing in Africa 14 Etannibi E.O. Alemika Chapter 3: Policing insurgency: Remembering apartheid 44 Elrena van der Spuy SECTION 2: COMMUNITY–POLICE NEXUS Chapter 4: Policing in the borderlands of Zimbabwe 63 Kudakwashe Chirambwi & Ronald Nare Chapter 5: Multiple counter-insurgency groups in north-eastern Nigeria 80 Benson Chinedu Olugbuo & Oluwole Samuel Ojewale SECTION 3: POLICING RESPONSES Chapter 6: Terrorism and rights protection in the Lake Chad basin 103 Amadou Koundy Chapter 7: Counter-terrorism and rights-based policing in East Africa 122 John Kamya Chapter 8: Boko Haram and rights-based policing in Cameroon 147 Polycarp Ngufor Forkum Chapter 9: Police organizational capacity and rights-based policing in Nigeria 163 Solomon E. -

Monguno Bama Gwoza

DTM Flash Report Windstorm and rainfall damages to IDP sites Nigeria IOM DTM Rapid Assessment Monguno, Bama and Gwoza LGAs (Local Government Areas) 24 June 2021 SUMMARY PP PPPP 200 Households 671 Individuals 3 sites 130 Damaged shelters 11 Damaged toilets 8 Damaged shower points With the onset of the rainy season in Nigeria’s conflict-affected Kukawa Guzamala northeastern state of Borno, varying degrees of damages are expected to GGSS 431 Camp Gubio ± infrastructures (self-made and constructed) in camps and camp-like settings. Usually, heavy rainfalls are accompanied by strong winds Nganzai Monguno causing serious damage to shelters of IDPs. Marte Between 17 and 23 June 2021, IOM’s DTM programme carried out Ngala assessments to ascertain the level of damage sustained in camps and Magumeri camp-like settings due to heavy windstorms and rainfall. Overall, 2 Kala/Balge Mafa Jere camps and 1 collective settlement in the LGAs Monguno, Bama and Dikwa Gwoza LGAs were assessed. The worst-hit of the camps assessed was Maiduguri Goverment Girls Secondary School (GGSS) camp in Monguno LGA where a heavy rainfall damaged 33 shelters, affecting an estimated 431 GSSSS camp individuals. Konduga 225 Bama In total, 130 shelters were damaged by storms, leaving a total of 200 households without shelter. Additionally, a total of 11 toilets and 8 Gwoza showers were damaged by storms. There was no casualty as a result of 20 Housing XXX Affected population Damboa 15 Camp the storms. Per Location LGA Sources: Esri, HERE, Garmin, USGS, Intermap, INCREMENT P, NRCan, Esri Japan, METI, Esri China 0 5 10 20 30 40 Affected LGAs (Hong Kong), Esri Korea, Esri (Thailand), NGCC, (c) OpenStreetMap contributors, and the GIS User Miles Community, Esri, HERE, Garmin, (c) OpenStreetMap contributors, and the GIS user community The maps in this report are for illustra�on purposes only. -

Breaking Boko Haram and Ramping up Recovery: US-Lake Chad Region 2013-2016

From Pariah to Partner: The US Integrated Reform Mission in Burma, 2009 to 2015 Breaking Boko Haram and Ramping Up Recovery Making Peace Possible US Engagement in the Lake Chad Region 2301 Constitution Avenue NW 2013 to 2016 Washington, DC 20037 202.457.1700 Beth Ellen Cole, Alexa Courtney, www.USIP.org Making Peace Possible Erica Kaster, and Noah Sheinbaum @usip 2 Looking for Justice ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This case study is the product of an extensive nine- month study that included a detailed literature review, stakeholder consultations in and outside of government, workshops, and a senior validation session. The project team is humbled by the commitment and sacrifices made by the men and women who serve the United States and its interests at home and abroad in some of the most challenging environments imaginable, furthering the national security objectives discussed herein. This project owes a significant debt of gratitude to all those who contributed to the case study process by recommending literature, participating in workshops, sharing reflections in interviews, and offering feedback on drafts of this docu- ment. The stories and lessons described in this document are dedicated to them. Thank you to the leadership of the United States Institute of Peace (USIP) and its Center for Applied Conflict Transformation for supporting this study. Special thanks also to the US Agency for International Development (USAID) Office of Transition Initiatives (USAID/OTI) for assisting with the production of various maps and graphics within this report. Any errors or omis- sions are the responsibility of the authors alone. ABOUT THE AUTHORS This case study was produced by a team led by Beth ABOUT THE INSTITUTE Ellen Cole, special adviser for violent extremism, conflict, and fragility at USIP, with Alexa Courtney, Erica Kaster, The United States Institute of Peace is an independent, nonpartisan and Noah Sheinbaum of Frontier Design Group. -

Nigeria's Constitution of 1999

PDF generated: 26 Aug 2021, 16:42 constituteproject.org Nigeria's Constitution of 1999 This complete constitution has been generated from excerpts of texts from the repository of the Comparative Constitutions Project, and distributed on constituteproject.org. constituteproject.org PDF generated: 26 Aug 2021, 16:42 Table of contents Preamble . 5 Chapter I: General Provisions . 5 Part I: Federal Republic of Nigeria . 5 Part II: Powers of the Federal Republic of Nigeria . 6 Chapter II: Fundamental Objectives and Directive Principles of State Policy . 13 Chapter III: Citizenship . 17 Chapter IV: Fundamental Rights . 20 Chapter V: The Legislature . 28 Part I: National Assembly . 28 A. Composition and Staff of National Assembly . 28 B. Procedure for Summoning and Dissolution of National Assembly . 29 C. Qualifications for Membership of National Assembly and Right of Attendance . 32 D. Elections to National Assembly . 35 E. Powers and Control over Public Funds . 36 Part II: House of Assembly of a State . 40 A. Composition and Staff of House of Assembly . 40 B. Procedure for Summoning and Dissolution of House of Assembly . 41 C. Qualification for Membership of House of Assembly and Right of Attendance . 43 D. Elections to a House of Assembly . 45 E. Powers and Control over Public Funds . 47 Chapter VI: The Executive . 50 Part I: Federal Executive . 50 A. The President of the Federation . 50 B. Establishment of Certain Federal Executive Bodies . 58 C. Public Revenue . 61 D. The Public Service of the Federation . 63 Part II: State Executive . 65 A. Governor of a State . 65 B. Establishment of Certain State Executive Bodies . -

Lessons from Colombia for Curtailing the Boko Haram Insurgency in Nigeria

Lessons From Colombia For Curtailing The Boko Haram Insurgency In Nigeria BY AFEIKHENA JEROME igeria is a highly complex and ethnically diverse country, with over 400 ethnic groups. This diversity is played out in the way the country is bifurcated along the lines of reli- Ngion, language, culture, ethnicity and regional identity. The population of about 178.5 million people in 2014 is made up of Christians and Muslims in equal measures of about 50 percent each, but including many who embrace traditional religions as well. The country has continued to experience serious and violent ethno-communal conflicts since independence in 1960, including the bloody and deadly thirty month fratricidal Civil War (also known as the Nigerian-Biafran war, 1967-70) when the eastern region of Biafra declared its seces- sion and which claimed more than one million lives. The most prominent of these conflicts recently pitch Muslims against Christians in a dangerous convergence of religion, ethnicity and politics. The first and most dramatic eruption in a series of recent religious disturbances was the Maitatsine uprising in Kano in December 1980, in which about 4,177 died. While the exact number of conflicts in Nigeria is unknown, because of a lack of reliable sta- tistical data, it is estimated that about 40 percent of all conflicts have taken place since the coun- try’s return to civilian rule in 1999.1 The increasing wave of violent conflicts across Nigeria under the current democratic regime is no doubt partly a direct consequence of the activities of ethno- communal groups seeking self-determination in their “homelands,” and of their surrogate ethnic militias that have assumed prominence since the last quarter of 2000. -

Canadian Environmental Assessment Agency Shell.Reviews@Ceaa‐Acee.Gc.Ca

Canadian Environmental Assessment Agency Shell.Reviews@ceaa‐acee.gc.ca October 1, 2012 Dear Joint Review Panel Secretariat, Re: Shell Jackpine Mine Expansion We are submitting this as a request to present evidence to the Joint Review Panel hearings. This letter documents our serious concerns regarding the proposed project. One of us (Anna Zalik) was born in Alberta, lived and worked in Edmonton through her late 20s and received her first degree from the University of Alberta. The other (Isaac ‘Asume’ Osuoka) was born in Nigeria’s Niger Delta where he later devoted most of his adult life to working with communities impacted by the oil industry. This letter is informed by our individual experiences and academic research on oil industry socio‐ecological practices since 1997 (Osuoka) and 2001 (Zalik) respectively, and collaborative research since 2008. From 2000 to the present Zalik conducted extensive field work in oil‐producing regions of Nigeria and Mexico. From 2005 onward she initiated research on the sociology of the oil and gas industry in the US and in Canada from onward, with field research visits conducted in Northern Alberta and British Columbia since 2008. This work has included interviews with community members, government agencies, NGOs and industry representatives. Both of us have presented research in various international fora. With regard to precedents set through previous Shell Jackpine EIA processes, several of which are now in the JRP public materials and analysed by the Pembina Institute and Ecojustice, Shell did not fulfill its earlier commitment to the Oil Sands Environmental Coalition (OSEC)1 to mitigate CO2 emissions. -

Tracking Displacement in the Lake Chad Basin

WITHIN AND BEYOND BORDERS: TRACKING DISPLACEMENT IN THE LAKE CHAD BASIN Regional Displacement and Human Mobility Analysis Displacement Tracking Matrix December 2016 INTERNATIONAL ORGANIZATION FOR MIGRATION (IOM) DTM activities are supported by: Chad │Cameroon│Nigeria 1 The opinions expressed in the report are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the International Organization for Migration (IOM). The designations employed and the presentation of material throughout the report do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of IOM concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area, or of its authorities, or concerning its frontiers or boundaries. IOM is committed to the principle that humane and orderly migration benefits migrants and society. As an intergovernmental organization, IOM acts with its partners in the international community: to assist in meeting the growing operational challenges of migration management; advance understanding of migration issues; encourage social and economic development through migration; and uphold the human dignity and well-being of migrants. PUBLISHER International Organization for Migration, Regional Office for West and Central Africa, Dakar, Senegal © 2016 International Organization for Migration (IOM) All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise without the prior written permission of the publisher. 2 IOM Regional Displacement Tracking Matrix INTRODUCTION Understanding and analysis of data, trends and patterns of human mobility is key to the provision of relevant and targeted humanitarian assistance. Humanitarian actors require information on the location and composition of the affected population in order to deliver services and respond to needs in a timely manner. -

ETT Report-No.32.V2

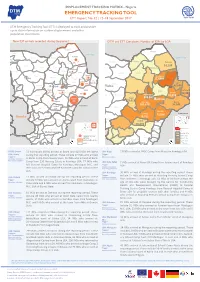

DISPLACEMENT TRACKING MATRIX - Nigeria DTM Nigeria EMERGENCY TRACKING TOOL ETT Report: No. 32 | 12–18 September 2017 IOM OIM DTM Emergency Tracking Tool (ETT) is deployed to track and provide up-to-date information on sudden displacement and other population movements New IDP arrivals recorded during the period DTM and ETT Cumulative Number of IDPs by LGA Abadam Abadam Yusufari Lake Chad Kukawa Yusufari Yunusari Mobbar Lake Chad± Nguru Karasuwa Niger Machina Yunusari Mobbar Abadam Kukawa Lake Chad Bade Guzamala 79 Nguru Karasuwa Kukawa Bursari 14,105 Geidam Gubio Bade Bade Guzamala Monguno Mobbar Nganzai Jakusko Bursari 6240 Marte Geidam Gubio Bade Guzamala Ngala Tarmua Monguno Magumeri Nganzai Jakusko Yobe 122,844 Marte 43 Gubio Monguno Jere Dikwa 7 Mafa Kala/BalgeYobe Ngala Maiduguri M.C. 122 Tarmua Nganzai Nangere Fune Damaturu Jigawa Magumeri 42,686 Borno 18 Yobe Marte Potiskum Ngala Kaga Konduga Bama Jere Mafa Kala/Balge Magumeri Dikwa 17 30 73 Yobe 49,480 Fika Gujba Nangere Fune Damaturu Maiduguri Mafa 74,858 Jere Dikwa Gwoza Potiskum Kaga Borno308,807 Kala-Balge MaiduBornoguri Damboa 799 19,619 KondugaKonduga Bama Gulani Cameroon Kag1a05,678 56,748 Chibok Konduga Fika Gujba Bama Biu 11 Madagali Askira/Uba Gwoza Michika Damboa Cameroon Kwaya Kusar 73,966Gwoza Hawul Damboa Bauchi Gombe Bayo Mubi North 76,795 Hong Gulani Shani Chibok Gombi Mubi South Madagali Biu Biu 16,378Chibok Maiha Askira/Uba Askira-Uba Inaccessible area Guyuk Song Michika Shelleng IDP severity Kwaya KusarKwaya Kusar Hawul Adamawa Hawul Less t han 10,788 Bauchi Gombe Bayo Mubi North Lamurde Number of new Bayo 10,788 - 25,813 HongAdamawa Numan Girei arrivals Shani Cameroon 25,813 - 56,749 Demsa Inaccessible area Shani Gombi Mubi South Yola South 56,749 - 122,770 Yola North Gombe 0 15 30 60 Km 122,770 Above Fufore LGAChad Adamawa Plateau Mayo-Belwa Shelleng Maiha Guyuk Song STATE: Borno 73 individuals (INDs) arrived at Bama and 129 INDs le� Bama LGA: Kaga 17 INDs arrived at NYSC Camp from Musari in Konduga LGA. -

The Counterinsurgency Campaign of the Nigerian Army: the Fight

The Counterinsurgency Campaign of the Nigerian Army: The Fight against the Boko-Haram Insurgency in North-East Nigeria, 1999-2017 Gilbert La’ankwap Yalmi Department of Politics and Contemporary History School of Arts and Media, University of Salford, Manchester, UK Supervisors Dr Samantha Newbery Professor Searle Alaric Submitted in Partial Fulfilment of the Requirements of the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy September 2020 TABLE OF CONTENTS TABLE OF CONTENTS ....................................................................................... i List of Figures ...................................................................................................... iv Acknowledgements.............................................................................................. v Dedication ........................................................................................................... vi Abbreviations ....................................................................................................vii Abstract ................................................................................................................ x INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................ 1 Gaps in the Literature and Opportunities for New Research ............................ 2 Statement of the Problem ................................................................................... 7 Objective and Significance ...............................................................................