DISSERTATION FACTORS AFFECTING COURSE SATISFACTION of ONLINE MALAYSIAN UNIVERSITY STUDENTS Submitted by Nasir M. Khalid Schoo

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Aeu 4Th Convocation Book

1 University 33 Countries asiaAe(OuniversityU � Accelerating • C a pa CI tysuilding Across Borders y 4 th Convocation •SUNDAY• 21 5T SEPTEMBER 2014 • KUALA LUMPUR ACCELERATING CAPACITY BUILDING ACROSS BORDERS 3 AeU is on a journey that will aid Malaysia and the region to transform into a more prosperous and inclusive Asian canvas-of-society through e-education. 4 ASIA e UNIVERSITY 4TH CONVOCATION 2014 TABLE OF CONTENTS Convocation Messages University Traditions Convocation Paraphernalia 00 Message from the Chairman 06 The Mace 00 Message from the ACD Representative 10 The Ceremonial Chair 00 Message from the President/CEO 12 The Academic Regalia 00 The School Hood Colour 00 About Asia e University The 4th Convocation Ceremony Programme 00 Vision, Mission, Objectives 00 University Awards 00 Rationale and Objectives 00 September 2014 Graduands 00 Core Values 00 University Background 00 In the words of AeU Community 00 University Profile 00 Media Highlights 00 Seven ‘E’s of the University 00 Revolutionising Learning 00 Learning Centres in Malaysia 00 International Collaborative Learning Centres 00 International Memberships 00 Schools and Programmes 00 Governance and Accountability Framework 00 Key Milestones 00 List of Past Honorary Degree Recipients 00 Notable Achievements 00 ACCELERATING CAPACITY BUILDING ACROSS BORDERS 5 Convocation MESSAGES 6 ASIA e UNIVERSITY 4TH CONVOCATION 2014 MESSAGE FROM THE CHAIRMAN AeU has opened the door to higher education, giving working adults the chance to continue learning and to upgrade their skills and knowledge, thus improving not only themselves, but also their families, professions and, ultimately, their country ACCELERATING CAPACITY BUILDING ACROSS BORDERS 7 MESSAGE FROM THE CHAIRMAN Dear Graduands, It is with great pleasure that I am able today to congratulate the graduands of 2014. -

Biennial Report

Biennial2008 & 2009 Report vision tion • na personal enrichment • professional advancement lf-paced e se nvironme ble • nt • conv da enient & or e • developing the afforda f d ble • e u ducat c ion for a ocess everyo f n o i t ne ning pr g r e v e r o n i t active learning process • academic freedom • equal learning apportunities learning equal • freedom academic • process learning active eco a r y e p • e n o tunities • r b engaging le e r p • t n e m h c i r n e l a n o s r ning oppor c onment • convenient & anf ing experience • active lear • learning without borders • inspiring learning • personal enrichment personal • learning inspiring • borders without l learning eedom • equal lear oductive lear WOU BIENNIAL REPORT f o m e c n a v d a l a n o i s s ae ting diversity • pr our full potencia educaartdiosn • • csellfe-pbarced envir s • formidable • nd ivating fertile mind ltivating fertile minds • unleash your full potencial • strategic growth • reach hig hstear • dynamic ocess • developing the nation • adcuacdaetmionic •f rcult cu gbhle • top-notch • superiiotyr •t harmoub gitiho ne • success • innovative • formidable • inspiring • reward realisation hdia ning pr ersity • prospe unleash y ng e le’s univ di for n e peop l t • th o r al l h on fo • active lear ati • n als u ti r acilitating educ t en u ULTIMATE FLEXIBILITY t r onment • f o e p ning envir g g r in oacho es • af lop w r ning • quality lear e t evolutionis g lear v ninh g experience • in e TO SHAPE YOUR FUTURE d • • i s n ie s it p n i r rtu exibe le appr o oductil ve lear p e 2008 & 2009 p a o r n n o i ti n ca dg ers • fl u • d s r e u e ating diversitp y • pr igh p h o l r t a i u n eq g ENJOY EVERYTHING ELSE THAT LIFE HAS TO OFFER WHILE AT IT. -

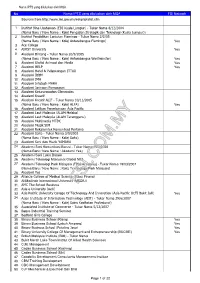

No Nama IPTS Yang Diluluskan Oleh MQA FSI Network Sources From

Nama IPTS yang diluluskan oleh MQA No Nama IPTS yang diluluskan oleh MQA FSI Network Sources from http://www.lan.gov.my/eskp/iptslist.cfm 1 Institut Bina Usahawan (EDI Kuala Lumpur) - Tukar Nama 8/12/2004 (Nama Baru / New Name : Kolej Pengajian Strategik dan Teknologi (Kuala Lumpur)) 2 Institut Pendidikan Lanjutan Flamingo - Tukar Nama 2/2/05 (Nama Baru / New Name : Kolej Antarabangsa Flamingo) Yes 3 Ace College 4 AIMST University Yes 5 Akademi Bintang - Tukar Nama 20/9/2005 (Nama Baru / New Name : Kolej Antarabangsa Westminster) Yes 6 Akademi Digital Animasi dan Media Yes 7 Akademi HELP Yes 8 Akademi Hotel & Pelancongan ITTAR 9 Akademi IBBM 10 Akademi IMH 11 Akademi Infotech MARA 12 Akademi Jaringan Pemasaran 13 Akademi Kejururawatan Gleneagles 14 Akademi Kreatif 15 Akademi Kreatif ALIF - Tukar Nama 10/11/2005 (Nama Baru / New Name : Kolej ALFA) Yes 16 Akademi Latihan Penerbangan Asia Pacific 17 Akademi Laut Malaysia (ALAM Melaka) 18 Akademi Laut Malaysia (ALAM Terengganu) 19 Akademi Multimedia MTDC 20 Akademi Muzik SIM 21 Akademi Rekabentuk Komunikasi Pertama 22 Akademi Saito - Tukar Nama 3/9/2003 (Nama Baru / New Name : Kolej Saito) 23 Akademi Seni dan Muzik YAMAHA 24 Akademi Seni Komunikasi Baruvi - Tukar Nama 15/2/2008 (Nama Baru / New Name : Akademi Yes) 25 Akademi Seni Lukis Dasein 26 Akademi Teknologi Maklumat Global NIIT 27 Akademi Teknologi Park Malaysia (TPM Academy) - Tukar Nama 19/03/2007 (Nama Baru / New Name : Kolej Technology Park Malaysia) 28 Akademi Yes 29 Allianze College of Medical Science (Pulau Pinang) 30 Al-Madinah -

Inspiring Greater Success Through

Inspiring GreaterLifelong Success Learning through Biennial Report 2016-2017 CONTENTS 2 Board of Governors Chairman’s Message 21 Management Board Heads of Regional Centres/ 4 Vice Chancellor’s Message 23 Regional Support Centres 6 Vision, Mission & Values 24 Academic Profile 7 Governance 43 Academic Support 8 Chancellor 49 Operational Support 9 Pro-Chancellor 57 Strategic Partnerships 10 Management Structure 58 Significant Events 11 Governance Structure 63 Workshops/Talks 12 Wawasan Education Foundation (WEF) 67 Towards a Quality Environment 14 Wawasan Open University Sdn Bhd 68 Corporate Social Responsibility Initiatives 16 The Board of Governors 69 Student Enrolment & Graduation 18 Organisational Structure 70 Study Grants & Scholarships 19 The Senate 72 Financial Summary WOU BIENNIAL REPORT 2016 - 2017 BOARD OF GOVERNORS CHAIRMAN’S MESSAGE It was Raj’s international reputation as a renowned expert in ODL (Open Distance Learning) and his ability to bring many excellent educators to WOU which enabled the institution to be awarded university status even before it opened its doors to the first batch of students in 2007. He guided and propelled WOU’s rise to prominence, not only in Malaysia, but also internationally, before he was succeeded by Emeritus Prof Dato’ Dr Wong Tat Meng. Under Raj’s leadership, WOU has garnered several international and national awards and recognition. Once again, our highest salutation and heartfelt appreciation to Raj! I was honoured and humbled to be appointed by the Wawasan Open University Sdn Bhd (WOUSB) Board of Directors (BOD) as the BoG Chairman to succeed Raj in March 2017. I chaired the BoG meeting for the first time on 31 May 2017. -

Moocs and Educational Challenges Around Asia and Europe First Published 2015 by KNOU Press

MOOCs and Educational Challenges around Asia and Europe First published 2015 by KNOU Press MOOCs and Educational Challenges around Asia and Europe Editor in Chief Bowon Kim Authors Bowon Kim, Wang Ying, Karanam Pushpanadham, Tsuneo Yamada, Taerim Lee, Mansor Fadzil, Latifah Abdol Latif, Tengku Amina Munira, Norazah Nordin, Mohamed Amin Embi, Helmi Norman, Juvy Lizette M. Gervacio, Jaitip Nasongkhla, Thapanee Thammetar, Shu-Hsiang (Ava) Chen, Mie Buhl, Lars Birch Andreasen, Henrik Jensen Mondrup, Rita Birzina, Alena Ilavska–Pistovcakova, and Inés Gil-Jaurena Publisher KNOU Press 54 Ihwajang-gil, Jongno-gu, Seoul, South Korea, 03088 http://press.knou.ac.kr Copyright G 2015 by KNOU Press. All rights reserved. ISBN 978-89-20-01809-1(93370) PDF version of this work is available under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Unported License. (See http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0/ for more) It can be accessible through the e-ASEM website at http://easem.knou.ac.kr. Table of Contents List of Contributors ·························································································· Part I Introduction 1. What do we know about MOOCs? ···························································· 3 Bowon Kim Part II MOOCs in Asia 2. A Case Study : The development of MOOCs in China ························· 9 Wang Ying 3. Universalizing university education : MOOCs in the era of knowledge based society ································································································ 21 Karanam -

ISAAA Brief# 45: from Monologue to Stakeholder Engagement

I S A A A INTERNATIONAL SERVICE FOR THE ACQUISITION OF AGRI-BIOTECH APPLICATIONS ISAAA Briefs BRIEF 45 From Monologue to Stakeholder Engagement: The Evolution of Biotech Communication Mariechel J. Navarro Kristine Grace Natividad-Tome Kaymart A. Gimutao No. 45 - 2013 BRIEF 45 From Monologue to Stakeholder Engagement: The Evolution of Biotech Communication Mariechel J. Navarro Kristine Grace Natividad-Tome Kaymart A. Gimutao No. 45 - 2013 Published by: The International Service for the Acquisition of Agri-biotech Applications (ISAAA). Copyright: ISAAA 2013. All rights reserved. Whereas ISAAA encourages the global sharing of information in Brief 45, no part of this publication maybe reproduced in any form or by any means, electronically, mechanically, by photocopying, recording or otherwise without the permission of the copyright owners. Reproduction of this publication, or parts thereof, for educational and non-commercial purposes is encouraged with due acknowledgment, subsequent to permission being granted by ISAAA. Citation: Navarro, M., K. Tome, and K. Gimutao. 2013. From Monologue to Stakeholder Engagement: The Evolution of Biotech Communication. ISAAA Brief No. 45. ISAAA: Ithaca, NY. ISBN: 978-1-892456-54-0 Info on ISAAA: For information about ISAAA, please contact the Center nearest you: ISAAA AmeriCenter ISAAA AfriCenter ISAAA SEAsiaCenter 105 Leland Lab PO Box 70, ILRI Campus c/o IRRI Cornell University Old Naivasha Road DAPO Box 7777 Ithaca NY 14853, U.S.A. Uthiru, Nairobi 00605 Metro Manila Kenya Philippines Electronic copy: E-copy available at http://www.isaaa.org/ or email [email protected] for additional information about this Brief. Table of Contents iii Preface v Authors and Contributors vii Abbreviations and Acronyms xi Tables and Figures 1 Introduction 5 Science Communication, Knowledge Management, and ISAAA’s Global Biotech Information Network 13 Communicating Crop Biotechnology: Experiences from the Field 27 Stakeholder Engagement: Enhancing the Sharing of Experiences 29 A. -

Higher Education in ASEAN

Higher Education in ASEAN © Copyright, The International Association of Universities (IAU), October, 2016 The contents of the publication may be reproduced in part or in full for non-commercial purposes, provided that reference to IAU and the date of the document is clearly and visibly cited. Publication prepared by Stefanie Mallow, IAU Printed by Suranaree University of Technology On the occasion of Hosted by a consortium of four Thai universities: 2 Foreword The Ninth ASEAN Education Ministers Qualifications Reference Framework (AQRF) Meeting (May 2016, in Malaysia), in Governance and Structure, and the plans to conjunction with the Third ASEAN Plus institutionalize the AQRF processes on a Three Education Ministers Meeting, and voluntary basis at the national and regional the Third East Asia Summit of Education levels. All these will help enhance quality, Ministers hold a number of promises. With credit transfer and student mobility, as well as the theme “Fostering ASEAN Community of university collaboration and people-to-people Learners: Empowering Lives through connectivity which are all crucial in realigning Education,” these meetings distinctly the diverse education systems and emphasized children and young people as the opportunities, as well as creating a more collective stakeholders and focus of coordinated, cohesive and coherent ASEAN. cooperation in education in ASEAN and among the Member States. The Ministers also The IAU is particularly pleased to note that the affirmed the important role of education in Meeting approved the revised Charter of the promoting a better quality of life for children ASEAN University Network (AUN), better and young people, and in providing them with aligned with the new developments in ASEAN. -

Download Fair Directory

UTP-Sureworks-Directory-OL.pdf 1 13/2/2020 11:16:17 AM C M Y CM MY CY CMY K Advert.pdf 1 2/11/2020 9:34:10 PM OPEOPEN DDAAYY & (T&C applies) abs C or gr or PTPTN M up f pply f A Y ARSHIPS om EPF simultaneously CM w fr SCHOL a MY withdr CY CMY K EVENT MANAGEMENT TION A GISTR RE FOR N W OPE NO 0 2 AKE 0 2 INT SCAN ME!! W NE APRIL MALAYSIAN INSTITUTE OF ART (535370-K) Malaysian Institute of Art - MIA malaysian.institute.of.art 294-299, Jln. Bandar 11, Tmn. Melawati, 53100 K. Lumpur. Inside this fair directory CONTENTS ADVERTISERS in this directory MESSAGE FROM 5 Welcome Message Which Pre-U Programme Should DATIN JERCY CHOO 10-11 You Pursue? 14-15 Careers in Artificial Intelligence ACCA (The Association of Chartered FROM SUREWORKS Certified Accountants) 9 Careers in Transportation AIMST University 38 20-21 and Logistics Asia Metropolitan University 25 Datin Jercy Choo 28-29 What is Civil Engineering? Asia Pacific University 39 Curtin University Malaysia 13 Welcome to the Education & What do Data Scientists Do? 32-33 HELP University 6-7 Further Studies Fair Series 51! The Right Career Based on Le Cordon Bleu Malaysia 23 36-37 Your Personality Malaysian Institute of Art (MIA) 2-3 Congratulations to all of you who recently completed your secondary school education! It is now Manipal International University CPS time to embark on the next step in your education journey. Find all the help you need at the fair Key Questions to Ask Exhibitors over these two weekends! 40-41 at the Fair Medic Ed Consultant Sdn Bhd IBC Melaka-Manipal Medical College CPS 5 Tips for Making Successful Methodist College Kuala Lumpur OBC It is important to gain as much information as possible on the education options available today 42 Scholarship Applications Monash University Malaysia 12 before settling on a course or institution. -

Terms and Conditions 1. Introduction #Myduitstory Short Video

#MyDuitStory Short Video Competition - Terms and Conditions 1. Introduction #MyDuitStory Short Video Competition (Competition) is a financial education initiative by Financial Education Network (FEN) led by Bank Negara Malaysia (the Organiser) in collaboration with the Ministry of Higher Education. The Competition aims to raise awareness on the importance of personal financial management among youth. 2. Eligibility The Competition is open to all Malaysian undergraduate students (Students) of participating universities (please refer to item 13 below). 3. Registration a) Students may submit an individual entry OR as a team of not more than 4 members (including Team Leader but excluding talents). b) Students are required to register at https://myduitstory.my/ by providing the following details: i. Name (Individual/Team Leader), e-mail address, contact number, and university name of the Individual/Team Leader the Students represent. ii. Upon registration, the Individual/Team Leader will receive a confirmation e-mail which include: ✓ a link to a Google Form for the Individual/Team Leader to fill in the details of the Lecturer(s) and the Team, if applicable. ✓ Facebook link to the Virtual Briefing by FINAS and AKPK. c) Team Members can be from the same or different participating university. d) Only participating universities for the Competition are eligible for the 'University With Most Entries Submitted’ prize category. e) The Lecturer is to validate the status of the Students. f) Students may submit multiple entries with different Coverage. 4. Important Dates a) Registration: 28 December 2020 – 31 January 2021 b) Virtual Briefing via Facebook Live: 13 January 2021 i. FINAS - on creating an engaging video and cultural nuances ii. -

Senarai Universiti (IPTS)

Lampiran B SENARAI INSTITUSI PENGAJIAN TINGGI SWASTA NO IPT 1 ALLIANZE UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF MEDICAL SCIENCES (AUCMS) 2 AL-MADINAH INTERNATIONAL UNIVERSITY (MEDIU) 3 ASIA E UNIVERSITY (AEU) 4 ASIA METROPOLITAN UNIVERSITY 5 ASIA PACIFIC UNIVERSITY OF TECHNOLOGY & INNOVATION (APU) 6 BINARY UNIVERSITY OF MANAGEMENT & ENTREPRENEURSHIP (BUME) 7 CITY UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF SCIENCE & TECHNOLOGY (CUCST) 8 CURTIN UNIVERSITY, SARAWAK 9 DRB-HICOM UNIVERSITY OF AUTOMOTIVE MALAYSIA 10 FIRST CITY UNIVERSITY COLLEGE 11 GLOBALNXT UNIVERSITY 12 HERIOT-WATT UNIVERSITY MALAYSIA (HWUM) 13 INTERNATIONAL MEDICAL UNIVERSITY (IMU) 14 INTERNATIONAL UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF ARTS AND SCIENCE (IUCAS) 15 INTERNATIONAL UNIVERSITY OF MALAYA WALES (IUMW) 16 KDU UNIVERSITY COLLEGE 17 KOLEJ UNIVERSITI AGROSAINS MALAYSIA 18 KOLEJ UNIVERSITI BESTARI 19 KOLEJ UNIVERSITI BORNEO UTARA (KUBU) 20 KOLEJ UNIVERSITI GEOMATIKA 21 KOLEJ UNIVERSITI HOSPITALITI BERJAYA 22 KOLEJ UNIVERSITI ISLAM ANTARABANGSA SELANGOR (KUIS) 23 KOLEJ UNIVERSITI ISLAM INSANIAH (KUIN) 24 KOLEJ UNIVERSITI ISLAM MELAKA (KUIM) 25 KOLEJ UNIVERSITI ISLAM PAHANG SULTAN AHMAD SHAH (KUIPSAS) 26 KOLEJ UNIVERSITI ISLAM PERLIS 27 KOLEJ UNIVERSITI ISLAM SAINS DAN TEKNOLOGI (KUIST) 28 KOLEJ UNIVERSITI ISLAM SULTAN AZLAN SHAH (KUISAS) 29 KOLEJ UNIVERSITI KDU PENANG 30 KOLEJ UNIVERSITI KPJ HEALTHCARE (KPJ HEALTHCARE UNIVERSITY COLLEGE) 31 KOLEJ UNIVERSITI LINCOLN 32 KOLEJ UNIVERSITI LINTON (LINTON UNIVERSITY COLLEGE) 33 KOLEJ UNIVERSITI POLY-TECH MARA KUALA LUMPUR (KUPTM) NO IPT 34 KOLEJ UNIVERSITI SAINS KESIHATAN MASTERSKILLS -

Terms and Conditions 1. Introduction #Myduitstory Short Video

#MyDuitStory Short Video Competition - Terms and Conditions 1. Introduction #MyDuitStory Short Video Competition (Competition) is a financial education initiative by Financial Education Network (FEN) led by Bank Negara Malaysia (the Organiser) in collaboration with the Ministry of Higher Education. The Competition aims to raise awareness on the importance of personal financial management among youth. 2. Eligibility The Competition is open to all Malaysian undergraduate students (Students) of participating universities (please refer to item 13 below). 3. Registration a) Students may submit an individual entry OR as a team of not more than 4 members (including Team Leader but excluding talents). b) Students are required to register at https://myduitstory.my/ by providing the following details: i. Name (Individual/Team Leader), e-mail address, contact number, and name of the university represented by the Individual/Team Leader. ii. Upon registration, the Individual/Team Leader will receive a confirmation e-mail which include: ✓ a link to a Google Form for the Individual/Team Leader to fill in the details of the Lecturer(s) and the Team, if applicable. ✓ Facebook link to the Virtual Briefing by FINAS and AKPK. c) Team Members can be from the same or different participating universities. d) Only registered university in the Google Form is eligible for the 'University With Most Entries Submitted’ prize category. e) The Lecturer is to validate the status of the Students. f) Students may submit multiple entries with different Coverage. 4. Important Dates a) Registration: 28 December 2020 – 31 January 2021 b) Virtual Briefing via Facebook Live: 13 January 2021 i. FINAS - on creating an engaging video and cultural nuances ii. -

Short Biography

Short Biography Prof. Dr. Md. Mamun Habib Prof. Dr. Md. Mamun Habib is a Professor at School of Business, Independent University, Bangladesh (IUB). In addition, Dr. Habib is the Visiting Scientist of University of Texas – Arlington, USA. Prior to that, he was Associate Professor at BRAC Business School, BRAC University, Bangladesh; Asia Graduate School of Business (AGSB) at UNITAR International University, Malaysia; Dept. of Operations Research/Decision Sciences, Universiti Utara Malaysia (UUM), Malaysia and Dept. of Operations Management, American International University-Bangladesh (AIUB). He is the Editor-in- Chief in International Journal of Supply Chain Management (IJSCM), London, UK (SCOPUS Indexed). He accomplished his Ph.D. and M.S. with outstanding performance in Computer & Engineering Management (CEM) under the Graduate School of Business (GSB) from Assumption University, Thailand. His Ph.D. research was in the field of Supply Chain Management. He has more than 18 years’ experience in the field of teaching as well as in training, workshops, consultancy and research. At present, he is supervising some Ph.D. students at locally and internationally. Furthermore, he has several Ph.D. involvements with UUM, UNIRAZAK, AIMST, UNITAR, Asia e University (AeU), Malaysia; Assumption University of Thailand; Institute for Technology and Management (ITM) – University and Birla Institute of Technology (BIT)–Deemed University, India, National Institute of Technology (NIT), India, SOA University, India; University of the Assumption, Philippines. He also involved with online learning programme at University of Roehampton (UoR), London, UK. He is actively involved with national and international research grant projects. As a researcher, Prof. Habib published about 140+ research papers, including Conference Proceedings, Journal articles, and book chapters/books.