Sample Material © UBC Press 2016 Trudeaumania

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Limits to Influence: the Club of Rome and Canada

THE LIMITS TO INFLUENCE: THE CLUB OF ROME AND CANADA, 1968 TO 1988 by JASON LEMOINE CHURCHILL A thesis presented to the University of Waterloo in fulfilment of the thesis requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History Waterloo, Ontario, Canada, 2006 © Jason Lemoine Churchill, 2006 Declaration AUTHOR'S DECLARATION FOR ELECTRONIC SUBMISSION OF A THESIS I hereby declare that I am the sole author of this thesis. This is a true copy of the thesis, including any required final revisions, as accepted by my examiners. I understand that my thesis may be made electronically available to the public. ii Abstract This dissertation is about influence which is defined as the ability to move ideas forward within, and in some cases across, organizations. More specifically it is about an extraordinary organization called the Club of Rome (COR), who became advocates of the idea of greater use of systems analysis in the development of policy. The systems approach to policy required rational, holistic and long-range thinking. It was an approach that attracted the attention of Canadian Prime Minister Pierre Trudeau. Commonality of interests and concerns united the disparate members of the COR and allowed that organization to develop an influential presence within Canada during Trudeau’s time in office from 1968 to 1984. The story of the COR in Canada is extended beyond the end of the Trudeau era to explain how the key elements that had allowed the organization and its Canadian Association (CACOR) to develop an influential presence quickly dissipated in the post- 1984 era. The key reasons for decline were time and circumstance as the COR/CACOR membership aged, contacts were lost, and there was a political paradigm shift that was antithetical to COR/CACOR ideas. -

Trudeau's Political Philosophy

TRUDEAU'S POLITICAL PHILOSOPHY: ITS IMPLICATIONS FOR LIBERTY AND PROGRESS by John L. Hiemstra A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the degree Master of Philosophy The Institute for Christian Studies Toronto, Ontario ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I wish to thank Dr. Bernard Zylstra for his assistance as my thesis supervisor, and Citizens for Public Justice for the grant of a study leave to enable me to complete the writing of this thesis. TABLE OF CONTENTS PREFACE...................................................... 2 I. BASIC ASSUMPTIONS.................................... 6 A. THE PRIMACY OF THE INDIVIDUAL...................... 6 1. The Individual as Rational....................... 9 2. The Individual and Liberty....................... 11 3. The Individual and Equality...................... 13 B. ETHICS AS VALUE SELECTION.......................... 14 C. HISTORY AS PROGRESS.................................. 16 D. PHILOSOPHY AS AUTONOMOUS............................ 19 II. THE INDIVIDUAL AND THE STATE....................... 29 A. SOCIETY AND STATE.................................... 29 B. JUSTICE AS PROCEDURE................................. 31 C. DEFINING THE COMMON GOOD IN A PROCEDURAL JUSTICE STATE......................................... 35 1. Participation and Democracy....................... 36 2. Majority Mechanism.................................. 37 D. PRELIMINARY QUESTIONS................................ 39 III. THE DISEQUILIBRIUM OF NATIONALISM................. 45 A. THE STATEMENT OF THE PROBLEM...................... -

Centre Mondial Du Pluralisme

GLOBAL CENTRE FOR PLURALISM | CENTRE MONDIAL DU PLURALISME 2008 Expert Roundtable on Canada’s Experience with Pluralism Canadian Multiculturalism: Historical and Political Contexts Karim H. Karim School of Journalism and Communication, Carleton University Ottawa, Canada Has multiculturalism worked in Canada? The answer to this question would depend on what one thinks are its goals and how one chooses to measure progress towards them. The varying meanings attached to words in the multiculturalism lexicon lead to expectations that are sometimes poles apart. Its terminology includes: pluralism, diversity, mosaic, melting pot, assimilation, integration, citizenship, national identity, core Canadian values, community, mainstream, majority, minority, ethnic, ethnocultural, race, racial, visible minority, immigrant, and diaspora. Those who believe that multiculturalism has succeeded point to the consistently high support for it in national surveys, the success stories of immigrants who ascend social, economic or political ladders, and the growing number of mixed marriages. For those on the other side, the relevant indicators seem to be high crime statistics among particular groups, the failure of some visible-minority groups to replicate the economic success of previous generations of immigrants, the apparent lack of integration into Canadian society, and the emigration of some recent arrivals from Canada. However, this paper takes the view that the scales are tipped in favour of multiculturalism’s success in Canada. The overall evidence for this is the comparatively low level of ethnic, racial or religious strife in this country compared to other western states such as the U.K., France, the Netherlands, Germany, Denmark, and the U.S.A. Large proportions of immigrants to Canada indicate that they are pleased to have come to this country rather than to any other western nation, even as they continue to face certain disadvantages (Adams, 2007). -

Canada Day As Part of a Political Master Brand

Celebrating the True North: Canada Day as part of a political master brand Justin Prno Thesis submitted to the University of Ottawa in partial Fulfillment of the requirements for the Master of Arts Department of Communication Faculty of Arts University of Ottawa © Justin Prno, Ottawa, Canada, 2019 CELEBRATING THE TRUE NORTH ii Abstract In Canada, the rise of political branding coincided with the adoption of the permanent campaign, creating an environment in which politicking is now normalized and politicization is expected. With Canada Day 2017 as a case study, this thesis adopts Marland’s Branding Lens Thesis (2016) as a conceptual framework to analyze if a national holiday became part of the Liberal Party of Canada’s master brand. The key conclusion of this thesis is that the Liberals integrated their ‘master brand’ into Canada Day 2017 by integrating political branding into their government communications. This thesis also shows that Justin Trudeau played a bigger role during Canada Day than expected by a Prime Minister. Significantly, this thesis shows the Liberal government altered the themes and messaging of Canada 150 to parallel that of their master brand, applying a Liberal tint to Canada Day and Canada 150. CELEBRATING THE TRUE NORTH iii Acknowledgements I’ve been known to talk a lot, but when it comes to the written word, I often come up short. Either way here goes... I would like to thank the community of people that surround me, near and far, past and present. Having you as part of my life makes taking these trips around the sun far more enjoyable. -

Canada's Response to the 1968 Soviet Invasion of Czechoslovakia

Canada’s Response to the 1968 Soviet Invasion of Czechoslovakia: An Assessment of the Trudeau Government’s First International Crisis by Angus McCabe A thesis submitted to the Faculty of Graduate and Postdoctoral Affairs in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in History Carleton University Ottawa, Ontario © 2019 Angus McCabe ii Abstract The new government of Pierre Trudeau was faced with an international crisis when, on 20 August 1968, the Soviet Union invaded Czechoslovakia. This study is the first full account of the Canadian government’s response based on an examination of the archival records of the Departments of External Affairs, National Defence, Manpower and Immigration, and the Privy Council Office. Underlying the government’s reaction were differences of opinion about Canada’s approach to the Cold War, its role at the United Nations and in NATO, the utility of the Department of External Affairs, and decisions about refugees. There was a delusory quality to each of these perspectives. In the end, an inexperienced government failed to heed some of the more competent advice it received concerning how best to meet Canada’s interests during the crisis. National interest was an understandable objective, but in this case, it was pursued at Czechoslovakia’s expense. iii Acknowledgements As anyone in my position would attest, meaningful work with Professor Norman Hillmer brings with it the added gift of friendship. The quality of his teaching, mentorship, and advice is, I suspect, the stuff of ages. I am grateful for the privilege of his guidance and comradeship. Graduate Administrator Joan White works kindly and tirelessly behind the scenes of Carleton University’s Department of History. -

Freedom, Democracy, and Nationalism in the Political Thought of Pierre Elliott Trudeau: a Conversation with Canadians

FREEDOM, DEMOCRACY, AND NATIONALISM IN THE POLITICAL THOUGHT OF PIERRE ELLIOTT TRUDEAU: A CONVERSATION WITH CANADIANS by SOMA ARRISON B.A., The University of Calgary, 1994 A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS in THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES (Department of Political Science) We accept this thesis as conforming to the required standard THE UNIVERSITY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA February 1996 © Sonia Arrison, 1996 In presenting this thesis in partial fulfilment of the requirements for an advanced degree at the University of British Columbia, I agree that the Library shall make it freely available for reference and study. I further agree that permission for extensive copying of this thesis for scholarly purposes may be granted by the head of my department or by his or her representatives. It is understood that copying or publication of this thesis for financial gain shall not be allowed without my written permission. Department The University of British Columbia Vancouver, Canada DE-6 (2/88) Abstract Pierre Elliott Trudeau's ideas on liberal democracy and political philosophy are relevant to Canadian life. He is a modern liberal democrat with a vision of the 'Good' society - what he terms the Just Society. The values of a Just Society are numerous, but perhaps, the most important are freedom, equality, and tolerance. These values are core to his theory and are often revealed in his battle against nationalism. Trudeau is radically opposed to notions of ethnic nationalism, such as French Canadian and Aboriginal nationalism, but he supports a type of civic nationalism within a federal, pluralistic system. -

Creation's Lab the Next Frontier in The

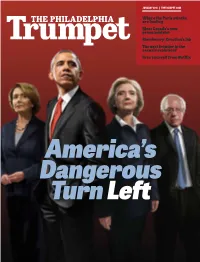

JANUARY 2016 | THETRUMPET.COM Where the Paris attacks are leading Meet Canada’s new prime minister Biomimicry: Creation’s lab The next frontier in the sexual revolution? Free yourself from Netflix America’s Dangerous Turn Left JANUARY 2016 VOL. 27, NO. 1 CIRC. 287,157 NIGHT OF TERROR A tarp covers one of the victims of the November 13 terrorist attacks in Paris. (GETTY IMAGES) COVER GARY DORNING/TRUMPET Cover Story Features Unriddling the Radical Worldview From the Editor of President Obama 2 Where the Paris Attacks Are Leading 1 The Roots of America’s Dangerous Like Father, Like Son? 11 Turn Left 6 Canada’s democratic system has empowered a dynasty Why Educators Are Attracted to Communism 9 that’s not big on democracy. Justin Trudeau’s Vision for Canada 31 Fear This Man 12 It is dangerous to underestimate Russia’s Vladimir Putin. Departments Will Putin Reignite the Balkans? 14 Worldwatch Pressure on Merkel, admiration for Europe’s next crisis could hit in what used to be Yugoslavia. Hitler?, Putin—savior of Russians, etc. 26 How Europe Conquered the Balkans 16 Societywatch Record gun-sales, etc. 29 Infographic: Biomimicry—Learning From Creation 18 Principles of Living Your Glorious, God-Given Power 33 The Next Frontier in the Sexual Revolution? 20 Discussion Board 34 Free Yourself From Netflix 22 Commentary Teaching the Unteachable 35 Will the Two Chinas Become One? 23 The Key of David Television Log 36 The time when Taiwan will be swallowed is approaching. More Trumpet Trumpet editor in chief Gerald Trumpet executive editor Stephen News and analysis A weekly digest Flurry’s weekly television program Flurry’s television program updated daily of important news theTrumpet.com/keyofdavid theTrumpet.com/trumpet_daily theTrumpet.com theTrumpet.com/trumpetweekly From the Editor Where the Paris Attacks Are Leading Most people are focusing on France’s reaction—but the ultimate aftereffect will consume all of Europe. -

Inclusion Society = Just Society

Inclusive Society = Just Society 1 Inclusive Society = Just Society Hello, I would like to thank my colleague, Ms. Elizabeth Sumbu and her staff at CANSA and members of the planning committee, for the invitation to be with you this evening to help you celebrate your theme “Specialized Excellence, a required quality service in Nova Scotia”. I am privileged to have worked in Cumberland County for 9 years and during that time to have had an affiliation with CANSA. Though it is not without some controversy, I have been pleased to see its mandate expand from an organization focused almost exclusively on the interests and concerns of ANS’s, to include specialization in the delivery of employment and other services to youth and persons with disabilities (PWD) and now generalized services to all persons of Cumberland County. As I looked over the list of the ten member organizations of the Collaborative Partnership Network Agencies, I can imagine that each of you have had similar organizational histories. Some I can imagine were formal agencies that took on the role of serving PWD; others were small community support agencies for PWD that grew to take on the role of providing specialized employment services to PWD. Whatever your origins, I would like to welcome and congratulate you. As is the role of the supper speaker I hope to inspire and encourage you in your work. So I’ve crafted a message for you that I’ve entitled “Inclusive Society = Just Society.” Perhaps because of the times in which I was born as much as to my personal ideologies, I consider myself to have been a Trudeau Liberal. -

The Liberal Third Option

The Liberal Third Option: A Study of Policy Development A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of Graduate Studies and Research in Partial Fuliiment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts in Political Science University of Regina by Guy Marsden Regina, Saskatchewan September, 1997 Copyright 1997: G. W. Marsden 395 Wellington Street 395, rue Wellington Ottawa ON KI A ON4 Ottawa ON KIA ON4 Canada Canada Your hie Votre rdtérence Our ME Notre référence The author has granted a non- L'auteur a accordé une licence non exclusive licence allowing the exclusive permettant à la National Library of Canada to Bibliothèque nationale du Canada de reproduce, loan, distibute or sell reproduire, prêter, distribuer ou copies of this thesis in microform, vendre des copies de cette thèse sous paper or electronic formats. la forme de microfiche/nlm, de reproduction sur papier ou sur format électronique. The author retains ownership of the L'auteur conserve la propriété du copyright in this thesis. Neither the droit d'auteur qui protège cette thèse. thesis nor substanîial extracts fiom it Ni la thèse ni des extraits substantiels may be printed or otherwise de celle-ci ne doivent être imprimés reproduced without the author's ou autrement reproduits sans son permission. autorisation. This study presents an analysis of the nationalist econornic policies enacted by the federal Liberal government during the 1970s and early 1980s. The Canada Development Corporation(CDC), the Foreign Investment Review Agency(FIRA), Petro- Canada(PetroCan) and the National Energy Prograrn(NEP), coliectively referred to as "The Third Option," aimed to reduce Canada's dependency on the United States. -

An Exploration of the Subjective Experience Of

THE MEDIATED SELF: AN EXPLORATION OF THE SUBJECTIVE EXPERIENCE OF MASS MEDIA CELEBRlTY FANSHIP Michelie Louise Gibson B.F.A., University of British Columbia, 1979 M.A., University of British Columbia, 1993 A THESIS SUBMITIED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS OF THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILSOPHY under Speciai Arrangements in the Faculty of Arts O Michelle Louise Gibson 2000 SIMON FRASER UNIVERSITY July 2000 Al1 rights reserved. This work may not be reproduced in whole or in part, by photocopy or other means, without permission of the author. Natio~lLibrary Bibliothèque nationale du Canada Acquisitions and Acquisitions et Bibliographie Services services bibliographiques 395 Wellington Street 395, rue Wellington Ottawa ON KiA ON4 Ottawa ON K1A ON4 Canada Canada The author has granted a non- L'auteur a accordé une licence non exclusive licence allowing the exclusive permettant à la National Library of Canada to Bïbliotheque nationale du Canada de reproduce, loan, distriibute or seli reproduire, prêter, distribuer ou copies of this thesis in microform, vendre des copies de cette thèse sous paper or electronic formats. la forme de microfiche/film, de reproduction sur papier ou sur format électronique. The author retains ownership of the L'auteur conserve la propriété du copyright in this thesis. Neither the droit d'auteur qui protège cette thèse. thesis nor substantial extracts fiom it Ni fa thèse ni des extraits substantiels may be printed or otherwise de celle-ci ne doivent être imprimés reproduced without the author's ou autrement reproduits sans son permission. autorisation. ABSTRACT While there are a sibstantial number of mass media fans in North America, limited research has been conducted on this population. -

AFFECTIVE PRACTICES of NATION and NATIONALISM on CANADIAN TELEVISION by MARUSYA BOCIURKIW BFA, Nova Scotia C

I FEEL CANADIAN: AFFECTIVE PRACTICES OF NATION AND NATIONALISM ON CANADIAN TELEVISION by MARUSYA BOCIURKIW B.F.A., Nova Scotia College of Art and Design, 1982 M.A., York University, 1999 A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in INTERDISCIPLINARY STUDIES THE UNIVERSITY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA October 2004 © Marusya Bociurkiw 2004 -11 - ABSTRACT In this dissertation, I examine how ideas about the nation are produced via affect, especially Canadian television's role in this discursive construction. I analyze Canadian television as a surface of emergence for nationalist sentiment. Within this commercial medium, U.S. dominance, Quebec separatism, and the immigrant are set in an oppositional relationship to Canadian nationalism. Working together, certain institutions such as the law and the corporation, exercise authority through what I call 'technologies of affect': speech-acts, music, editing. I argue that the instability of Canadian identity is re-stabilized by a hyperbolic affective mode that is frequently produced through consumerism. Delimited within a fairly narrow timeframe (1995 -2002), the dissertation's chronological starting point is the Quebec Referendum of October 1995. It concludes at another site of national and international trauma: media coverage of September 11, 2001 and its aftermath. Moving from traumatic point to traumatic point, this dissertation focuses on moments in televised Canadian history that ruptured, or tried to resolve, the imagined community of nation, and the idea of a national self and national others. I examine television as a marker of an affective Canadian national space, one that promises an idea of 'home'. -

Understandings of Multiculturalism Among Newcomers to Canada

Volume 27 Refuge Number 1 A “Great” Large Family: Understandings of Multiculturalism among Newcomers to Canada Christopher J. Fries and Paul Gingrich Abstract Résumé Analysts have taken positions either supporting or attacking Les analystes ont pris position soit pour ou contre la poli- multicultural policy, yet there is insuffi cient research con- tique du multiculturalisme, mais il y a insuffi sance de cerning the public policy of multiculturalism as it is under- la recherche sur la politique publique du multicultura- stood and practiced in the lives of Canadians. Th is analysis lisme tel qu’on le comprend et pratique dans la vie des approaches multiculturalism as a text which is constitu- Canadiens. Cette analyse aborde le multiculturalisme en ent of social relations within Canadian society. Data from tant que texte constitutif des relations sociales au sein de the Regina Refugee Research Project are analyzed within la société canadienne. Des données statistiques du Regina Nancy Fraser’s social justice framework to explore the Refugee Research Project sont analysées dans le cadre de manner in which multiculturalism and associated poli- justice sociale élaboré par Nancy Fraser afi n d’explorer la cies are understood and enacted in the lived experience of manière dont le multiculturalisme et les politiques conne- newcomers. Newcomers’ accounts of multiculturalism are xes sont comprises et adoptées dans le vécu des nouveaux compared with fi ve themes identifi ed via textual analysis of arrivants. Les témoignages de nouveaux arrivants sur le the Canadian Multiculturalism Act—diversity, harmony, multiculturalisme sont comparés à cinq thèmes identifi és equality, overcoming barriers, and resource.