Multiculturalism As Transformative?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

1 2011 Guelph Jazz Festival Colloquium Panel with Cecil Foster

1 2011 Guelph Jazz Festival Colloquium Panel with Cecil Foster Writing Jazz: Gesturing Towards the Possible Interview conducted by Paul Watkins Transcribed by Elizabeth Johnstone Edited by Paul Watkins PW: So, this is the morning plenary. It’s more of an interview, a discussion of wits, somewhat dialogic, with Dr. Cecil Foster, who is a Canadian novelist. You may also know him as an essayist, journalist, and scholar. He was born in Bridgetown, Barbados, where he began working for the Caribbean News Agency. You can read his autobiography, which was published around 1998 and is called Island Wings, which describes his experience of growing up in Barbados and eventually emigrating to Canada, which he did in 1979. He worked for the Toronto Star, as well as the Globe and Mail. He was also a special advisor to Ontario’s Ministry of Culture. His most recent books, Where Race Does Not Matter, and Blackness and Modernity, explore the potentials for multiculturalism in Canada. Currently he is an associate professor of Sociology here at the University of Guelph, and hopefully today we’ll talk about multiculturalism, as well as improvisation, and how those intersections may relate to his own writing process. Without further ado I introduce Dr. Cecil Foster. CF: Good morning and let me say a special hello to all of my friends and colleagues, and people that will become friends and colleagues. It certainly is a pleasure to be here. I rather enjoy being here at Guelph. I have now gone through the ranks from assistant, to associate, to full professor, to end up being, one of the, I hope Ajay would consider me to be a writer. -

Trudeau's Political Philosophy

TRUDEAU'S POLITICAL PHILOSOPHY: ITS IMPLICATIONS FOR LIBERTY AND PROGRESS by John L. Hiemstra A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the degree Master of Philosophy The Institute for Christian Studies Toronto, Ontario ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I wish to thank Dr. Bernard Zylstra for his assistance as my thesis supervisor, and Citizens for Public Justice for the grant of a study leave to enable me to complete the writing of this thesis. TABLE OF CONTENTS PREFACE...................................................... 2 I. BASIC ASSUMPTIONS.................................... 6 A. THE PRIMACY OF THE INDIVIDUAL...................... 6 1. The Individual as Rational....................... 9 2. The Individual and Liberty....................... 11 3. The Individual and Equality...................... 13 B. ETHICS AS VALUE SELECTION.......................... 14 C. HISTORY AS PROGRESS.................................. 16 D. PHILOSOPHY AS AUTONOMOUS............................ 19 II. THE INDIVIDUAL AND THE STATE....................... 29 A. SOCIETY AND STATE.................................... 29 B. JUSTICE AS PROCEDURE................................. 31 C. DEFINING THE COMMON GOOD IN A PROCEDURAL JUSTICE STATE......................................... 35 1. Participation and Democracy....................... 36 2. Majority Mechanism.................................. 37 D. PRELIMINARY QUESTIONS................................ 39 III. THE DISEQUILIBRIUM OF NATIONALISM................. 45 A. THE STATEMENT OF THE PROBLEM...................... -

Centre Mondial Du Pluralisme

GLOBAL CENTRE FOR PLURALISM | CENTRE MONDIAL DU PLURALISME 2008 Expert Roundtable on Canada’s Experience with Pluralism Canadian Multiculturalism: Historical and Political Contexts Karim H. Karim School of Journalism and Communication, Carleton University Ottawa, Canada Has multiculturalism worked in Canada? The answer to this question would depend on what one thinks are its goals and how one chooses to measure progress towards them. The varying meanings attached to words in the multiculturalism lexicon lead to expectations that are sometimes poles apart. Its terminology includes: pluralism, diversity, mosaic, melting pot, assimilation, integration, citizenship, national identity, core Canadian values, community, mainstream, majority, minority, ethnic, ethnocultural, race, racial, visible minority, immigrant, and diaspora. Those who believe that multiculturalism has succeeded point to the consistently high support for it in national surveys, the success stories of immigrants who ascend social, economic or political ladders, and the growing number of mixed marriages. For those on the other side, the relevant indicators seem to be high crime statistics among particular groups, the failure of some visible-minority groups to replicate the economic success of previous generations of immigrants, the apparent lack of integration into Canadian society, and the emigration of some recent arrivals from Canada. However, this paper takes the view that the scales are tipped in favour of multiculturalism’s success in Canada. The overall evidence for this is the comparatively low level of ethnic, racial or religious strife in this country compared to other western states such as the U.K., France, the Netherlands, Germany, Denmark, and the U.S.A. Large proportions of immigrants to Canada indicate that they are pleased to have come to this country rather than to any other western nation, even as they continue to face certain disadvantages (Adams, 2007). -

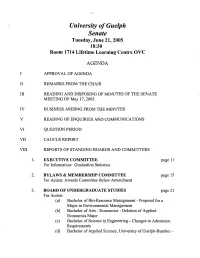

Senate Tuesday, June 21,2005 18:30 Room 1714 Lifetime Learning Centre OVC

University of Guelph Senate Tuesday, June 21,2005 18:30 Room 1714 Lifetime Learning Centre OVC AGENDA APPROVAL OF AGENDA REMARKS FROM THE CHAIR READING AND DISPOSING OF MINUTES OF THE SENATE MEETING OF May 17,2005. IV BUSINESS ARISING FROM THE MINUTES v READING OF ENQUIRIES AND COMMUNICATIONS VI QUESTION PERIOD VII CAUCUS REPORT VIII REPORTS OF STANDING BOARDS AND COMMITTEES 1. EXECUTIVE COMMITTEE page 11 For Information: Graduation Statistics BYLAWS & MEMBERSHIP COMMITTEE page 15 For Action: Awards Committee Bylaw Amendment BOARD OF UNDERGRADUATE STUDIES page 21 For Action: (a) Bachelor of Bio-Resource Management - Proposal for a Major in Environmental Management (b) Bachelor of Arts - Economics - Deletion of Applied Economics Major (c) Bachelor of Science in Engineering - Changes to Admission Requirements (d) Bachelor of Applied Science, University of Guelph-Humber - Changes to Admission Requirements (e) Academic Schedule of Dates, 2006-2007 For Information: (0 Course, Additions, Deletions and Changes (g) Editorial Calendar Amendments (i) Grade Reassessment (ii) Readmission - Credit for Courses Taken During Rustication 4. BOARD OF GRADUATE STUDIES page 9 1 For Action: (a) Proposal for a Master of Fine Art in Creative Writing (b) Proposal for a Master of Arts in French Studies For Information: (c) Graduate Faculty Appointments (d) Course Additions, Deletions and Changes 5. COMMITTEE ON AWARDS page 177 For Information: (a) Awards Approved June 2004 - May 2005 (b) Winegard, Forster and Governor General Medal Winners 6. COMMITTEE ON UNIVERSITY PLANNING page 181 For Action: Change of Name for Department of Human Biology and Nutritional Science IX COU RE,PORT X OTHER BUSINESS XI ADJOURNMENT Please note: The Senate Executive will meet at 18:15 in Room 1713 Lifetime Learning Centre OVC just prior to Senate 1r;ne Birrell, Secretary of Senate University of Guelph Senate Tuesday, June 21": 2005 REPORT FROM THE SENATE EXECUTIVE COMMITTEE Chair: Al Sullivan <[email protected]~ For Information: Graduation Statistics - June 2005 Membership: A. -

Freedom, Democracy, and Nationalism in the Political Thought of Pierre Elliott Trudeau: a Conversation with Canadians

FREEDOM, DEMOCRACY, AND NATIONALISM IN THE POLITICAL THOUGHT OF PIERRE ELLIOTT TRUDEAU: A CONVERSATION WITH CANADIANS by SOMA ARRISON B.A., The University of Calgary, 1994 A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS in THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES (Department of Political Science) We accept this thesis as conforming to the required standard THE UNIVERSITY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA February 1996 © Sonia Arrison, 1996 In presenting this thesis in partial fulfilment of the requirements for an advanced degree at the University of British Columbia, I agree that the Library shall make it freely available for reference and study. I further agree that permission for extensive copying of this thesis for scholarly purposes may be granted by the head of my department or by his or her representatives. It is understood that copying or publication of this thesis for financial gain shall not be allowed without my written permission. Department The University of British Columbia Vancouver, Canada DE-6 (2/88) Abstract Pierre Elliott Trudeau's ideas on liberal democracy and political philosophy are relevant to Canadian life. He is a modern liberal democrat with a vision of the 'Good' society - what he terms the Just Society. The values of a Just Society are numerous, but perhaps, the most important are freedom, equality, and tolerance. These values are core to his theory and are often revealed in his battle against nationalism. Trudeau is radically opposed to notions of ethnic nationalism, such as French Canadian and Aboriginal nationalism, but he supports a type of civic nationalism within a federal, pluralistic system. -

Inclusion Society = Just Society

Inclusive Society = Just Society 1 Inclusive Society = Just Society Hello, I would like to thank my colleague, Ms. Elizabeth Sumbu and her staff at CANSA and members of the planning committee, for the invitation to be with you this evening to help you celebrate your theme “Specialized Excellence, a required quality service in Nova Scotia”. I am privileged to have worked in Cumberland County for 9 years and during that time to have had an affiliation with CANSA. Though it is not without some controversy, I have been pleased to see its mandate expand from an organization focused almost exclusively on the interests and concerns of ANS’s, to include specialization in the delivery of employment and other services to youth and persons with disabilities (PWD) and now generalized services to all persons of Cumberland County. As I looked over the list of the ten member organizations of the Collaborative Partnership Network Agencies, I can imagine that each of you have had similar organizational histories. Some I can imagine were formal agencies that took on the role of serving PWD; others were small community support agencies for PWD that grew to take on the role of providing specialized employment services to PWD. Whatever your origins, I would like to welcome and congratulate you. As is the role of the supper speaker I hope to inspire and encourage you in your work. So I’ve crafted a message for you that I’ve entitled “Inclusive Society = Just Society.” Perhaps because of the times in which I was born as much as to my personal ideologies, I consider myself to have been a Trudeau Liberal. -

Program Guide a Festival for Readers and Writers

PROGRAM GUIDE A FESTIVAL FOR READERS AND WRITERS SEPTEMBER 25 – 29, 2019 HOLIDAY INN KINGSTON WATERFRONT penguinrandomca penguinrandomhouse.ca M.G. Vassanji Anakana Schofield Steven Price Dave Meslin Guy Gavriel Kay Jill Heinerth Elizabeth Hay Cary Fagan Michael Crummey KINGSTON WRITERSFEST PROUD SPONSOR OF PROUD SPONSOR OF KINGSTON WRITERSFEST Michael Crummey Cary Fagan Elizabeth Hay FULL PAGEJill Heinerth AD Guy Gavriel Kay Dave Meslin Steven Price Anakana Schofield M.G. Vassanji penguinrandomhouse.ca penguinrandomca Artistic Director's Message ow to sum up a year’s activity in a few paragraphs? One Hthing is for sure; the team has not rested on its laurels after a bang-up tenth annual festival in 2018. We’ve focussed our sights on the future, and considered how to make our festival more diverse, intriguing, relevant, inclusive and welcoming of those who don’t yet know what they’ve been missing, and those who may have felt it wasn’t a place for them. To all newcomers, welcome! We’ve programmed the most diverse festival yet. It wasn’t hard to fnd a range of stunning new writers in all genres, and seasoned writers with powerful new works. We’ve included the stories of women, the stories of Indigenous writers, Métis writers, writers of different experiences, cultural backgrounds, and orientations. Our individual and collective experience and understanding are sure to be enriched by these fresh perspectives, and new insights into the past. We haven’t forgotten our roots in good story-telling, presenting a variety of uplifting, entertaining, and thought-provoking fction and non-fction events. -

The Liberal Third Option

The Liberal Third Option: A Study of Policy Development A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of Graduate Studies and Research in Partial Fuliiment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts in Political Science University of Regina by Guy Marsden Regina, Saskatchewan September, 1997 Copyright 1997: G. W. Marsden 395 Wellington Street 395, rue Wellington Ottawa ON KI A ON4 Ottawa ON KIA ON4 Canada Canada Your hie Votre rdtérence Our ME Notre référence The author has granted a non- L'auteur a accordé une licence non exclusive licence allowing the exclusive permettant à la National Library of Canada to Bibliothèque nationale du Canada de reproduce, loan, distibute or sell reproduire, prêter, distribuer ou copies of this thesis in microform, vendre des copies de cette thèse sous paper or electronic formats. la forme de microfiche/nlm, de reproduction sur papier ou sur format électronique. The author retains ownership of the L'auteur conserve la propriété du copyright in this thesis. Neither the droit d'auteur qui protège cette thèse. thesis nor substanîial extracts fiom it Ni la thèse ni des extraits substantiels may be printed or otherwise de celle-ci ne doivent être imprimés reproduced without the author's ou autrement reproduits sans son permission. autorisation. This study presents an analysis of the nationalist econornic policies enacted by the federal Liberal government during the 1970s and early 1980s. The Canada Development Corporation(CDC), the Foreign Investment Review Agency(FIRA), Petro- Canada(PetroCan) and the National Energy Prograrn(NEP), coliectively referred to as "The Third Option," aimed to reduce Canada's dependency on the United States. -

Understandings of Multiculturalism Among Newcomers to Canada

Volume 27 Refuge Number 1 A “Great” Large Family: Understandings of Multiculturalism among Newcomers to Canada Christopher J. Fries and Paul Gingrich Abstract Résumé Analysts have taken positions either supporting or attacking Les analystes ont pris position soit pour ou contre la poli- multicultural policy, yet there is insuffi cient research con- tique du multiculturalisme, mais il y a insuffi sance de cerning the public policy of multiculturalism as it is under- la recherche sur la politique publique du multicultura- stood and practiced in the lives of Canadians. Th is analysis lisme tel qu’on le comprend et pratique dans la vie des approaches multiculturalism as a text which is constitu- Canadiens. Cette analyse aborde le multiculturalisme en ent of social relations within Canadian society. Data from tant que texte constitutif des relations sociales au sein de the Regina Refugee Research Project are analyzed within la société canadienne. Des données statistiques du Regina Nancy Fraser’s social justice framework to explore the Refugee Research Project sont analysées dans le cadre de manner in which multiculturalism and associated poli- justice sociale élaboré par Nancy Fraser afi n d’explorer la cies are understood and enacted in the lived experience of manière dont le multiculturalisme et les politiques conne- newcomers. Newcomers’ accounts of multiculturalism are xes sont comprises et adoptées dans le vécu des nouveaux compared with fi ve themes identifi ed via textual analysis of arrivants. Les témoignages de nouveaux arrivants sur le the Canadian Multiculturalism Act—diversity, harmony, multiculturalisme sont comparés à cinq thèmes identifi és equality, overcoming barriers, and resource. -

Historic Resources Study of Pullman National Monument, Illinois

Michigan Technological University Digital Commons @ Michigan Tech Michigan Tech Publications 12-2019 Historic Resources Study of Pullman National Monument, Illinois Laura Walikainen Rouleau Michigan Technological University, [email protected] Sarah Fayen Scarlett Michigan Technological University, [email protected] Steven A. Walton Michigan Technological University, [email protected] Timothy Scarlett Michigan Technological University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.mtu.edu/michigantech-p Part of the Archaeological Anthropology Commons, Other Anthropology Commons, Social and Cultural Anthropology Commons, and the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Walikainen Rouleau, L., Scarlett, S. F., Walton, S. A., & Scarlett, T. (2019). Historic Resources Study of Pullman National Monument, Illinois. Report for the National Park Service. Retrieved from: https://digitalcommons.mtu.edu/michigantech-p/14692 Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.mtu.edu/michigantech-p Part of the Archaeological Anthropology Commons, Other Anthropology Commons, Social and Cultural Anthropology Commons, and the United States History Commons National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior Midwest Archeological Center Lincoln, Nebraska Historic Resource Survey PULLMAN NATIONAL HISTORICAL MONUMENT Town of Pullman, Chicago, Illinois Dr. Laura Walikainen Rouleau Dr. Sarah Fayen Scarlett Dr. Steven A. Walton and Dr. Timothy J. Scarlett Michigan Technological University 31 December 2019 HISTORIC RESOURCE STUDY OF PULLMAN NATIONAL MONUMENT, Illinois Dr. Laura Walikainen Rouleau Dr. Sarah Fayen Scarlett Dr. Steven A. Walton and Dr. Timothy J. Scarlett Department of Social Sciences Michigan Technological University Houghton, MI 49931 Submitted to: Dr. Timothy M. Schilling Midwest Archeological Center, National Park Service 100 Centennial Mall North, Room 44 7 Lincoln, NE 68508 31 December 2019 Historic Resource Study of Pullman National Monument, Illinois by Laura Walikinen Rouleau Sarah F. -

House of Commons Debates

House of Commons Debates VOLUME 147 Ï NUMBER 094 Ï 2nd SESSION Ï 41st PARLIAMENT OFFICIAL REPORT (HANSARD) Monday, June 2, 2014 Speaker: The Honourable Andrew Scheer CONTENTS (Table of Contents appears at back of this issue.) 5961 HOUSE OF COMMONS Monday, June 2, 2014 The House met at 11 a.m. Hamilton, and which I am on most days when I am back in the constituency. Prayers Despite all of these accomplishments and many more, above all else Lincoln Alexander was a champion of young people. He was convinced that if a society did not take care of its youth, it would have no future. He also knew that education and awareness were PRIVATE MEMBERS' BUSINESS essential in changing society's prejudices and sometimes flawed presuppositions about others. That is why it is so fitting that so many Ï (1105) schools are named after him. He himself had been a young person [English] who sought to make his place in his community so that he could contribute to his country. LINCOLN ALEXANDER DAY ACT Mr. David Sweet (Ancaster—Dundas—Flamborough—West- As a young boy, Lincoln Alexander faced prejudice daily, but his dale, CPC) moved that Bill S-213, An Act respecting Lincoln mother encouraged him to be two or three times as good as everyone Alexander Day, be read the second time and referred to a committee. else, and indeed he was. Lincoln Alexander followed his mother's He said: Mr. Speaker, I was proud to introduce Bill S-213, an act advice and worked hard to overcome poverty and prejudice. -

Social Justice in a Multicultural Society: Experience from the UK

Social Justice in a Multicultural Society: Experience from the UK Gary Craig1, University of Hull ABSTRACT Social justice is a contested concept. For example, some on the left argue for equality of outcomes, those on the right for equality of opportunities, and there are differing emphases on the roles of state, market and individual in achieving a socially just society. These differences in emphasis are critical when it comes to examining the impact that public policy has on minority ethnic groups. Social justice should not be culture- blind any more than it can be gender-blind yet the overwhelming burden of evidence from the UK shows that public policy, despite the political rhetoric of fifty years of governments since large-scale immigration started, has failed to deliver social justice to Britain’s minorities. In terms of outcomes, in respect for and recognition of diversity and difference, in their treatment, and in the failure of governments to offer an effective voice to minorities, the latter continue to be marginalised in British social, economic and political life. This is not an argument for abandoning the project of multiculturalism, however, but for ensuring that it is framed within the values of social justice. Social Justice in the UK: Current Political Discourse Social justice is a concept that has been debated--in different guises--for thousands of years. It is only since the 1970s, however, and particularly in the past fifteen years, that it has re-emerged into political discourse, most notably amongst governments which have characterized themselves as social democratic or “Third Way.” As Miller argues (2001), in the context of the development of liberal democratic societies, “the quest for social justice is a natural consequence of the spread of enlightenment” (p.