Laden Der Druckdatei

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

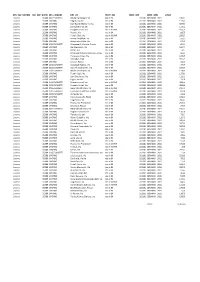

Lista Location English.Xlsx

LOCATIONS LIST Postal City Name Address Code ABANO TERME 35031 DIBRA KLODIANA VIA GASPARE GOZZI 3 ABBADIA SAN SALVATORE 53021 FABBRINI CARLO PIAZZA GRAMSCI 15 ABBIATEGRASSO 20081 BANCA DI LEGNANO VIA MENTANA ACCADIA 71021 NIGRO MADDALENA VIA ROMA 54 ACI CATENA 95022 PRINTEL DI STIMOLO PRINCIPATO VIA NIZZETI 43 ACIREALE 95024 LANZAFAME ALESSANDRA PIAZZA MARCONI 12 ACIREALE 95024 POLITI WALTER VIA DAFNICA 104 102 ACIREALE 95024 CERRA DONATELLA VIA VITTORIO EMANUELE 143 ACIREALE 95004 RIV 6 DI RIGANO ANGELA MARIA VIA VITTORIO EMANUELE II 69 ACQUAPENDENTE 01021 BONAMICI MANUELA VIA CESARE BATTISTI 1 ACQUASPARTA 05021 LAURETI ELISA VIA MARCONI 40 ACQUEDOLCI 98076 MAGGIORE VINCENZO VIA RICCA SALERNO 43 ACQUI TERME 15011 DOC SYSTEM VIA CARDINAL RAIMONDI 3 ACQUI TERME 15011 RATTO CLAUDIA VIA GARIBALDI 37 ACQUI TERME 15011 CASSA DI RISPARMIO DI ALESSAND CORSO BAGNI 102 106 ACQUI TERME 15011 CASSA DI RISPARMIO DI ALESSAND VIA AMENDOLA 31 ACRI 87041 MARCHESE GIUSEPPE ALDO MORO 284 ADRANO 95031 LA NAIA NICOLA VIA A SPAMPINATO 13 ADRANO 95031 SANTANGELO GIUSEPPA PIAZZA UMBERTO 8 ADRANO 95031 GIULIANO CARMELA PIAZZA SANT AGOSTINO 31 ADRIA 45011 ATTICA S R L RIVIERA GIACOMO MATTEOTTI 5 ADRIA 45011 SANTINI DAVIDE VIA CHIEPPARA 67 ADRIA 45011 FRANZOSO ENRICO CORSO GIUSEPPE MAZZINI 73 AFFI 37010 NIBANI DI PAVONE GIULIO AND C VIA DANZIA 1 D AGEROLA 80051 CUOMO SABATO VIA PRINCIPE DI PIEMONTE 11 AGIRA 94011 BIONDI ANTONINO PIAZZA F FEDELE 19 AGLIANO TERME 14041 TABACCHERIA DELLA VALLE VIA PRINCIPE AMEDEO 27 29 AGNA 35021 RIVENDITA N 7 VIA MURE 35 AGRIGENTO -

Chapter One: Introduction

CHANGING PERCEPTIONS OF IL DUCE TRACING POLITICAL TRENDS IN THE ITALIAN-AMERICAN MEDIA DURING THE EARLY YEARS OF FASCISM by Ryan J. Antonucci Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts in the History Program YOUNGSTOWN STATE UNIVERSITY August, 2013 Changing Perceptions of il Duce Tracing Political Trends in the Italian-American Media during the Early Years of Fascism Ryan J. Antonucci I hereby release this thesis to the public. I understand that this thesis will be made available from the OhioLINK ETD Center and the Maag Library Circulation Desk for public access. I also authorize the University or other individuals to make copies of this thesis as needed for scholarly research. Signature: Ryan J. Antonucci, Student Date Approvals: Dr. David Simonelli, Thesis Advisor Date Dr. Brian Bonhomme, Committee Member Date Dr. Martha Pallante, Committee Member Date Dr. Carla Simonini, Committee Member Date Dr. Salvatore A. Sanders, Associate Dean of Graduate Studies Date Ryan J. Antonucci © 2013 iii ABSTRACT Scholars of Italian-American history have traditionally asserted that the ethnic community’s media during the 1920s and 1930s was pro-Fascist leaning. This thesis challenges that narrative by proving that moderate, and often ambivalent, opinions existed at one time, and the shift to a philo-Fascist position was an active process. Using a survey of six Italian-language sources from diverse cities during the inauguration of Benito Mussolini’s regime, research shows that interpretations varied significantly. One of the newspapers, Il Cittadino Italo-Americano (Youngstown, Ohio) is then used as a case study to better understand why events in Italy were interpreted in certain ways. -

Pietro Gori's Anarchism: Politics and Spectacle (1895–1900)*

IRSH 62 (2017), pp. 425–450 doi:10.1017/S0020859017000359 © 2017 Internationaal Instituut voor Sociale Geschiedenis Pietro Gori’s Anarchism: Politics and Spectacle (1895–1900)* E MANUELA M INUTO Department of Political Science, University of Pisa Via Serafini 3, 56126 Pisa, Italy E-mail: [email protected] ABSTRACT: This paper discusses Pietro Gori’s charismatic leadership of the Italian anarchist movement at the turn of the nineteenth century and, in particular, the characteristics of his political communication. After a discussion of the literature on the topic, the first section examines Gramsci’s derogatory observations on the characteristics and success of the communicative style adopted by anarchist activists such as Gori. The second investigates the political project underpinning the kind of “organized anarchism” that Gori championed together with Malatesta. The third section unveils Gori’s communication strategy when promoting this project through those platforms considered by Gramsci as being primary schools of political alphabetization in liberal Italy: trials, funerals, commemorations, and celebrations. Particular attention is devoted to the trials, which effectively demonstrated Gori’s modern political skills. The analysis of Gori’s performance at the trials demonstrates Gramsci’s mistake in identifying Gori simply as one of the champions of political sentimentalism. He spoke very well, but he spoke the language of the people. And the people flocked in when his name was announced for a rally or for a conference.1 INTRODUCTION In the twenty years between 1890–1911, Pietro Gori was one of the most famous anarchists in Italy and abroad and, long after his death, he continued to be a key figure in the socialist and labour movement of his native country. -

The Origins of the European Integration: Staunch Italians, Cautious British Actors and the Intelligence Dimension (1942-1946) Di Claudia Nasini

Eurostudium3w gennaio-marzo 2014 The Origins of the European Integration: Staunch Italians, Cautious British Actors and the Intelligence Dimension (1942-1946) di Claudia Nasini The idea of unity in Europe is a concept stretching back to the Middle Ages to the exponents of the Respublica Christiana. Meanwhile the Enlightenment philosophers and political thinkers recurrently advocated it as a way of embracing all the countries of the Continent in some kind of pacific order1. Yet, until the second half of the twentieth century the nationalist ethos of Europeans prevented any limitation of national sovereignty. The First World War, the millions of casualties and economic ruin in Europe made the surrendering of sovereignty a conceivable way of overcoming the causes of recurring conflicts by bringing justice and prosperity to the Old World. During the inter-war years, it became evident that the European countries were too small to solve by their own efforts the problem of a modern economy2. As a result of the misery caused by world economic crisis and the European countries’ retreating in economic isolationism, various forms of Fascism emerged in almost half of the countries of Europe3. The League of Nations failed to prevent international unrest because it had neither the political power nor the material strength to enable itself to carry 1 Cfr. Andrea Bosco, Federal Idea, vol. I, The History of Federalism from Enlightenment to 1945, London and New York, Lothian foundation, 1991, p. 99 and fll.; and J.B. Duroselle, “Europe as an historical concept”, in C. Grove Haines (ed.by) European Integration, Baltimore, 1958, pp. -

World History Week 3 Take Home Packet

Local District South Students: We hope that you are adjusting to the difficult situation we all find ourselves in and that you are taking time to rest, care for yourself and those you love, and do something everyday to lift your spirits. We want you to know that you are missed and that we have been working hard to develop ways to support you. We want to stay connected with you and provide you with opportunities to learn while you are at home. We hope that you find these activities interesting and that they provide you with something to look forward to over the course of the next week. Stay home; stay healthy; stay safe. We cannot wait until we see you again. Sincerely, The Local District South Instructional Team and your school family World History Week 3 Take Home Packet Student Name_________________________________________________________________________ School________________________________________ Teacher_______________________________ Students: Each of the Social Science Learning Opportunities Packet was developed based on a portion of the standards framework. The mini-unit you will be working on this week, is based on these questions from the framework: ● What was totalitarianism, and how was it implemented in similar and different ways in Japan, Germany, Italy, and the Soviet Union? We encourage you to engage in the Extended Learning Opportunity if you are able. Over the course of the next week, please do the activities listed for each day. Week 3, Day 1 1. Read, “Life in a Totalitarian Country” and annotate using the annotation bookmark. 2. Answer the quiz questions. 3. Write a response to this prompt:Observe: How does the text describe the relationship between fear and totalitarian governments? Week 3, Day 2 1. -

Book Reviews

italian culture, Vol. xxxii No. 2, September 2014, 138–60 Book Reviews Fictions of Appetite: Alimentary Discourses in Italian Modernist Literature. By Enrico Cesaretti. Pp. vii + 272. Oxford: Peter Lang. 2013. Aside from a few, notable examples, such as Gian-Paolo Biasin’s I sapori della modernità (1991), gastro-criticism is a fairly new multi-disciplinary approach to literature that incorpo- rates literary studies, anthropology, sociology, semiotics and history to explore cultural production. Enrico Cesaretti’s gastro-critical approach to Italian Modernism brings together articles previously published; but here they are revised in order to read early twentieth century Italian writers and texts from a new perspective. The four chapters explore both well-known and nearly forgotten texts by authors such as F. T. Marinetti, Aldo Palazzeschi, Paola Masino, Massimo Bontempelli, and Luigi Pirandello through the common thematic of food, eating, depravation and hunger. Cesaretti notes that “virtually every major twentieth-century Western intellectual from Freud onward, has refl ected on the multiple cultural roles and implications of food and eating” (3). Modernism brought renewed focus on the body, so the trope of food, or lack thereof, becomes an important semiotic concern for writers of the period. Cesaretti’s selection of authors and texts stems from a chronological closeness more so than a great stylistic affi nity, and he is conscious of trying to unite his authors under the umbrella of the term Modernism, which, as he notes, has been problematic in Italian literary critical circles. For Cesaretti, these fi ve authors all emphasize food, hunger, and related tropes in their works because of historical reality (food shortages in Italy during the interwar years among others) and because of Modernism’s emphasis on the body and its functions. -

“Critica Sociale” E La Rivoluzione Russa (1917-1926)

SPES – Rivista della Società di Politica, Educazione e Storia, Suppl. di “Ricerche Pedagogiche” ISSN 2533-1663 (online) Anno X, n. 10, Luglio – Dicembre 2019, pp. 105-132 “Critica Sociale” e la rivoluzione russa (1917-1926) Giovanna Savant La rivoluzione di febbraio è accolta con favore dall’ala moderata del PSI, che ha in “Critica Sociale” il principale organo di espressione. La caduta dello zar sembra aprire una fase democratica il cui scopo è di trasformare l’autocrazia russa in un moderno regime rappresentativo. La rivista turatiana segue prima con simpatia e poi con preoccupazione crescente le vicende russe, fino a quando l’avvento al pote- re dei bolscevichi cancella ogni speranza di uno sviluppo democratico. Da questo momento, il giudizio sulla Russia dividerà le due anime del PSI in modo irrimedia- bile: mentre i massimalisti guarderanno alla dittatura bolscevica come a un model- lo, per i moderati costituirà un’aberrazione dei canoni del materialismo storico. The Revolution of February is welcomed by the moderate wing of the Italian Social- ist Party, which has in “Critica Sociale” the main media outlet. The Czar's fall seems to open a democratic phase that aims to get Russian autocracy into a modern representative system. The review of Turati, at first, is pleased about the Russian events, but later it shows a rising concern until the Bolsheviks come to power de- stroying all hope for democratic development. Since this moment, the judgment on Russia will separate irreparably the two souls of the Italian Socialist Party: the maximalists see the Bolshevik dictatorship as a model, while the moderates consider it an aberration of the principles of the historical materialism. -

Monitoraggio Gennaio 2021.Pdf

DES_IMP_DISTRIB COD_IMP_DISTRIB DES_COMUNE DES_VIA PARTE_IMP MESE_ISPE MESE_ISPE2 LUNGH Livorno 35389 COLLESALVETTI Alcide De Gasperi, Via rete in BP 202101 GENNAIO 2021 108,54 Livorno 35389 LIVORNO Fulgidi, Via dei rete in BP 202101 GENNAIO 2021 117,83 Livorno 35389 LIVORNO Don David Albertario, Via rete in BP 202101 GENNAIO 2021 659,93 Livorno 35389 LIVORNO Carabinieri, Via dei rete in BP 202101 GENNAIO 2021 117,18 Livorno 35389 LIVORNO Giorgio La Pira, Via rete in AP/MP 202101 GENNAIO 2021 185,25 Livorno 35389 LIVORNO Rossini, Via rete in BP 202101 GENNAIO 2021 68,70 Livorno 35389 LIVORNO Fratelli Gigli, Via rete in AP/MP 202101 GENNAIO 2021 258,57 Livorno 35389 LIVORNO Enrico Bartelloni, Via rete in BP 202101 GENNAIO 2021 55,55 Livorno 35389 LIVORNO Alessandro Volta, Via rete in BP 202101 GENNAIO 2021 67,65 Livorno 35389 COLLESALVETTI Giuseppe Di Vittorio, Piazza rete in BP 202101 GENNAIO 2021 81,15 Livorno 35389 LIVORNO San Francesco, Via rete in BP 202101 GENNAIO 2021 100,71 Livorno 35389 LIVORNO Azzati, Via rete in BP 202101 GENNAIO 2021 9,12 Livorno 35389 LIVORNO Emanuele Filiberto di Savoia, Largo rete in BP 202101 GENNAIO 2021 66,16 Livorno 35389 LIVORNO Francesco Crispi, Via rete in BP 202101 GENNAIO 2021 127,26 Livorno 35389 LIVORNO D'Azeglio, Scali rete in BP 202101 GENNAIO 2021 301,29 Livorno 35389 LIVORNO Cavour, Piazza rete in BP 202101 GENNAIO 2021 34,07 Livorno 35389 COLLESALVETTI Giuseppe Romita, Via rete in BP 202101 GENNAIO 2021 37,79 Livorno 35389 COLLESALVETTI Niccolò Machiavelli, Via rete in BP 202101 GENNAIO 2021 -

Amadeo Bordiga and the Myth of Antonio Gramsci

AMADEO BORDIGA AND THE MYTH OF ANTONIO GRAMSCI John Chiaradia PREFACE A fruitful contribution to the renaissance of Marxism requires a purely historical treatment of the twenties as a period of the revolutionary working class movement which is now entirely closed. This is the only way to make its experiences and lessons properly relevant to the essentially new phase of the present. Gyorgy Lukács, 1967 Marxism has been the greatest fantasy of our century. Leszek Kolakowski When I began this commentary, both the USSR and the PCI (the Italian Communist Party) had disappeared. Basing myself on earlier archival work and supplementary readings, I set out to show that the change signified by the rise of Antonio Gramsci to leadership (1924-1926) had, contrary to nearly all extant commentary on that event, a profoundly negative impact on Italian Communism. As a result and in time, the very essence of the party was drained, and it was derailed from its original intent, namely, that of class revolution. As a consequence of these changes, the party would play an altogether different role from the one it had been intended for. By way of evidence, my intention was to establish two points and draw the connecting straight line. They were: one, developments in the Soviet party; two, the tandem echo in the Italian party led by Gramsci, with the connecting line being the ideology and practices associated at the time with Stalin, which I label Center communism. Hence, from the time of Gramsci’s return from the USSR in 1924, there had been a parental relationship between the two parties. -

"Sulla Scissione Socialdemocratica Del 1947"

"SULLA SCISSIONE SOCIALDEMOCRATICA DEL 1947" 26-04-2018 - STORIE & STORIE La storiografia politica é ormai compattamente schierata nel giudicare validi, anche perché - cosí si dice - confermati dalla storia, i motivi che, nel gennaio 1947, portarono alla scissione detta „di Palazzo Barberini", che l´11 gennaio di quell´anno diede vita alla socialdemocrazia italiana. Il PSIUP (1), che era riuscito a riunire nello stesso partito tutte le "anime" del socialismo italiano, si spacco´ allora in due tronconi: il PSI di Nenni e il PSDI (2) di Saragat. I due leader, nel corso del precedente congresso di Firenze dell´ 11-17 aprile1946, avevano pronunciato due discorsi che, per elevatezza ideologica e per tensione ideale, sono degni di figurare nella storia del socialismo, e non solo di quello italiano. Il primo, Nenni, aveva marcato l´accento sulla necessitá di salvaguardare l´unitá della classe lavoratrice, in un momento storico in cui i tentativi di restaurazione capitalista erano ormai evidenti; il secondo aveva messo l´accento sulla necessitá di tutelare l´autonomia socialista, l´unica capace di costruire il socialismo nella democrazia, in un momento in cui l´ombra dello stalinismo si stendeva su tutta l´Europa centrale e orientale. Pochi mesi dopo, si diceva, la drammatica scissione tra „massimalisti" e „riformisti" (3), che la storia, o meglio, gli storici, avrebbero poi giudicato necessaria e lungimirante, persino provvidenziale. Essi, infatti, hanno dovuto registrare il trionfo del riformismo, ormai predicato anche dai nipotini di Togliatti e dagli italoforzuti. „Il termine riformista é oggi talmente logorato dall´uso, dall´abuso e dal cattivo uso, che ha perso ogni significato" (4). -

ESS9 Appendix A3 Political Parties Ed

APPENDIX A3 POLITICAL PARTIES, ESS9 - 2018 ed. 3.0 Austria 2 Belgium 4 Bulgaria 7 Croatia 8 Cyprus 10 Czechia 12 Denmark 14 Estonia 15 Finland 17 France 19 Germany 20 Hungary 21 Iceland 23 Ireland 25 Italy 26 Latvia 28 Lithuania 31 Montenegro 34 Netherlands 36 Norway 38 Poland 40 Portugal 44 Serbia 47 Slovakia 52 Slovenia 53 Spain 54 Sweden 57 Switzerland 58 United Kingdom 61 Version Notes, ESS9 Appendix A3 POLITICAL PARTIES ESS9 edition 3.0 (published 10.12.20): Changes from previous edition: Additional countries: Denmark, Iceland. ESS9 edition 2.0 (published 15.06.20): Changes from previous edition: Additional countries: Croatia, Latvia, Lithuania, Montenegro, Portugal, Slovakia, Spain, Sweden. Austria 1. Political parties Language used in data file: German Year of last election: 2017 Official party names, English 1. Sozialdemokratische Partei Österreichs (SPÖ) - Social Democratic Party of Austria - 26.9 % names/translation, and size in last 2. Österreichische Volkspartei (ÖVP) - Austrian People's Party - 31.5 % election: 3. Freiheitliche Partei Österreichs (FPÖ) - Freedom Party of Austria - 26.0 % 4. Liste Peter Pilz (PILZ) - PILZ - 4.4 % 5. Die Grünen – Die Grüne Alternative (Grüne) - The Greens – The Green Alternative - 3.8 % 6. Kommunistische Partei Österreichs (KPÖ) - Communist Party of Austria - 0.8 % 7. NEOS – Das Neue Österreich und Liberales Forum (NEOS) - NEOS – The New Austria and Liberal Forum - 5.3 % 8. G!LT - Verein zur Förderung der Offenen Demokratie (GILT) - My Vote Counts! - 1.0 % Description of political parties listed 1. The Social Democratic Party (Sozialdemokratische Partei Österreichs, or SPÖ) is a social above democratic/center-left political party that was founded in 1888 as the Social Democratic Worker's Party (Sozialdemokratische Arbeiterpartei, or SDAP), when Victor Adler managed to unite the various opposing factions. -

Capitolo Primo La Formazione Di Bettino Craxi

CAPITOLO PRIMO LA FORMAZIONE DI BETTINO CRAXI 1. LA FAMIGLIA Bettino, all’anagrafe Benedetto Craxi nasce a Milano, alle 5 di mattina, il 24 febbraio 1934, presso la clinica ostetrica Macedonio Melloni; primo di tre figli del padre Vittorio Craxi, avvocato siciliano trasferitosi nel capoluogo lombardo e di Maria Ferrari, originaria di Sant’Angelo Lodigiano. 1 L’avvocato Vittorio è una persona preparata nell’ambito professionale ed ispirato a forti ideali antifascisti. Vittorio Craxi è emigrato da San Fratello in provincia di Messina a causa delle sue convinzioni socialiste. Trasferitosi nella città settentrionale, lascia nella sua terra una lunga tradizione genealogica, cui anche Bettino Craxi farà riferimento. La madre, Maria Ferrari, figlia di fittavoli del paese lodigiano è una persona sensibile, altruista, ma parimenti ferma, autorevole e determinata nei principi.2 Compiuti sei anni, Bettino Craxi è iscritto al collegio arcivescovile “De Amicis” di Cantù presso Como. Il biografo Giancarlo Galli narra di un episodio in cui Bettino Craxi è designato come capo classe, in qualità di lettore, per augurare il benvenuto all’arcivescovo di Milano, cardinal Ildefonso Schuster, in visita pastorale. 3 La presenza come allievo al De Amicis è certificata da un documento custodito presso la Fondazione Craxi. Gli ex alunni di quella scuola, il 31 ottobre 1975 elaborano uno statuto valido come apertura di cooperativa. Il resoconto sarà a lui indirizzato ed ufficialmente consegnato il 10 ottobre 1986, allor quando ritornerà all’istituto in veste di Presidente del Consiglio; in quell’occasione ricorderà la sua esperienza durante gli anni scolastici e commemorerà l’educatore laico e socialista a cui la scuola è dedicata.