University of Sydney [email protected]

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Some Principles of the Use of Macro-Areas Language Dynamics &A

Online Appendix for Harald Hammarstr¨om& Mark Donohue (2014) Some Principles of the Use of Macro-Areas Language Dynamics & Change Harald Hammarstr¨om& Mark Donohue The following document lists the languages of the world and their as- signment to the macro-areas described in the main body of the paper as well as the WALS macro-area for languages featured in the WALS 2005 edi- tion. 7160 languages are included, which represent all languages for which we had coordinates available1. Every language is given with its ISO-639-3 code (if it has one) for proper identification. The mapping between WALS languages and ISO-codes was done by using the mapping downloadable from the 2011 online WALS edition2 (because a number of errors in the mapping were corrected for the 2011 edition). 38 WALS languages are not given an ISO-code in the 2011 mapping, 36 of these have been assigned their appropri- ate iso-code based on the sources the WALS lists for the respective language. This was not possible for Tasmanian (WALS-code: tsm) because the WALS mixes data from very different Tasmanian languages and for Kualan (WALS- code: kua) because no source is given. 17 WALS-languages were assigned ISO-codes which have subsequently been retired { these have been assigned their appropriate updated ISO-code. In many cases, a WALS-language is mapped to several ISO-codes. As this has no bearing for the assignment to macro-areas, multiple mappings have been retained. 1There are another couple of hundred languages which are attested but for which our database currently lacks coordinates. -

0=AFRICAN Geosector

2= AUSTRALASIA geosector Observatoire Linguistique Linguasphere Observatory page 123 2=AUSTRALASIA geosector édition princeps foundation edition DU RÉPERTOIRE DE LA LINGUASPHÈRE 1999-2000 THE LINGUASPHERE REGISTER 1999-2000 publiée en ligne et mise à jour dès novembre 2012 published online & updated from November 2012 This geosector covers 223 sets of languages (1167 outer languages, composed of 2258 inner languages) spoken or formerly spoken by communities in Australasia in a geographic sequence from Maluku and the Lesser Sunda islands through New Guinea and its adjacent islands, and throughout the Australian mainland to Tasmania. They comprise all languages of Australasia (Oceania) not covered by phylosectors 3=Austronesian or 5=Indo-European. Zones 20= to 24= cover all so-called "Papuan" languages, spoken on Maluku and the Lesser Sunda islands and the New Guinea mainland, which have been previously treated within the "Trans-New Guinea" hypothesis: 20= ARAFURA geozone 21= MAMBERAMO geozone 22= MANDANGIC phylozone 23= OWALAMIC phylozone 24= TRANSIRIANIC phylozone Zones 25= to 27= cover all other so-called "Papuan" languages, on the New Guinea mainland, Bismarck archipelago, New Britain, New Ireland and Solomon islands, which have not been treated within the "Trans-New Guinea" hypothesis: 25= CENDRAWASIH geozone 26= SEPIK-VALLEY geozone 27= BISMARCK-SEA geozone Zones 28= to 29= cover all languages spoken traditionally across the Australian mainland, on the offshore Elcho, Howard, Crocodile and Torres Strait islands (excluding Darnley island), and formerly on the island of Tasmania. An "Australian" hypothesis covers all these languages, excluding the extinct and little known languages of Tasmania, comprising (1.) an area of more diffuse and complex relationships in the extreme north, covered here by geozone 28=, and (2.) a more closely related affinity (Pama+ Nyungan) throughout the rest of Australia, covered by 24 of the 25 sets of phylozone 29=. -

Building Capacity for Multidisciplinary Landscape Assessment in Papua: Three Phases of Training and Pilot Assessments in the Mamberamo Basin

P.O. Box 6596 JKPWB Tel. (62) 251 622622 Jakarta 10065 Fax (62) 251 622100 CIFOR Indonesia Building Capacity for Multidisciplinary Landscape Assessment in Papua: three phases of training and pilot assessments in the Mamberamo Basin A report based on work jointly undertaken in 2004 by the Center for International Forestry Research, Conservation International (Papua Program), Lembaga Ilmu Pengetahuan Indonesia (LIPI), 18 Papua- based Trainees, and the people of Papasena-I and Kwerba Villages. MLA in Papua, Page 1 SUMMARY Conservation International (CI) supports a number of ongoing initiatives in the Mamberamo area of Papua. The principal aims are to strengthen biodiversity conservation and environmental management and facilitate the creation of a ‘Mamberamo Biodiversity Conservation Corridor’, which links currently established protected areas through strategically placed ‘indigenous forest reserves’. Two primary requirements are 1) to find suitable means to allow local communities to participate in decision-making processes, and 2) capacity building of locally based researchers to assist in planning and developing this program. The MLA training reported here is designed to build capacity and assess options and opportunities within this context. The Centre for International Forestry Research (CIFOR) has developed methods for assessing 'what really matters' to communities living in tropical forest landscapes. Known as the Multidisciplinary Landscape Assessment or ‘MLA' (see http://www.cifor.cgiar.org/mla), this approach enhances understanding amongst conservation and development practitioners, policy makers and forest communities. Information yielded through the MLA can identify where local communities’ interests and priorities might converge (or conflict) with conservation and sustainable development goals. CIFOR's MLA methods have already been applied in Indonesia (East Kalimantan), Bolivia and Cameroon. -

Languages of the World--Indo-Pacific

REPORT RESUMES ED 010 365 48 LANGUAGES OF THE WORLD- -INDO-PACIFIC FASCICLE FIVE. BY- VOEGELIN, FLORENCE M. INDIANA UNIV., BLOOMINGTON REPORT NUMBER NDEA- VI -63-18 PUB DATE DEC 65 CONTRACT OECSAE9468 FORS PRICE MFS0.16 HC -$4.96 124P. ANTHROPOLOGICAL LINGUISTICS, 7(9)/11141 DEC.1965 DESCRIPTORS- *INDO PACIFICLANGUAGES, *LANGUAGES,ARCHIVES OF LANGUAGES OF THE 'WORLD,BLOOMINGTON, INDIANA THE NON-AUSTRONESIANLANGUAGES CENTERIN1 IN NEWGUINEA ARE LISTED AND DESCRIBEDIN THIS REPORT. IN ADDITION, SENTENCE SAMPLERS OF THEUSARUFA AND WANTOATLANGUAGES ARE PROVIDED. (THE REPORT ISPART OF A SERIES, ED 010350 IC ED 010 367.) (JK) trt 63-/f3 U. S. DEPARTMENTOF HEALTH, 1`11 EDUCATION ANDWELFARE Office of Education c'4 This document 5/C- C: has been reproducedexactly ea received person or orgargzation from the °deluging it Pointsct view or opinions stated do net mensal*represent official CZ) pos:then or policy. Ottica at Edu Mon AnthropologicalLinguistics ti Volume 7 Number 9 December 1965 I LANGUAGES OF THE WORLD:-.. INDOPACIFIC FASCICLE FIVE A Publication of the ARCHIVES OF LANGUAGESOF THE WORLD Anthropology Department Indiana University ANTHROPOLOGICAL LINGUISTICS is designedprimarily, but not exclusively, for the immediate publication of data-oriented papers for which attestationis available in the form oftape recordings on deposit in the Archives of Languages of the World.This does not imply that contributorswill be re- stricted to scholars working in tle Archivesat Indiana University; infact, one motivation far the of ANTHROPOLOGICAL LINGUISTICS -

West Irian Bibliography (Ch.5- Text Version)

You have found a section of * Papuaweb's searchable full-text version of West Irian: A Bibliography by van Baal, Galis, Koentjaraningrat (1984) This document is made available via www.papuaweb.org and reproduced with the kind permission of the Koninklijk Instituut voor Taal-, Land- en Volkenkunde, The Netherlands (www.kitlv.nl) with all rights reserved, 2005. This is an automatically generated PDF document interpolated from a high-resolution scan (600dpi) of the original text. This document was not proof-read for errors in content or formatting. Papuaweb may eventually prepare a corrected full-text version of this document subject to available project resources and the priorities of website users. For an error-free digital facsimile of this document (image-based PDF) Please visit this document from the www. papuaweb.org homepage or go directly to http://www.papuaweb.org/dlib/bk1/kitlv/bib/index.html. (* This note is to assist users who have “parachuted” into this page from Google, Yahoo, ...) 28 West Irian: A Bibliography Rapport Bevolkingsonderzoek 1958 Rapport van het Bevolkingsonderzoek onder de Marid-anim van Nederlands Zuid-Nieuw-Guinea; South Pacific Commission Population Studies, Proj. S 18, [mimeographed]. Sande .A.J. van der 1907 Ethnography and Anthropology, Nova Guinea I I I , 390 pp . , plates. LINGUISTICS Sensus penduduk 1971 Sensus penduduk di propinsi Irian Barat 1971, Jayapura: Kantor Sensus dan Statistik Propinsi Irian. Simmons, R.T. et al. V.I. Introduction 1971 A compendium of Melanesian genetic data, Victoria (Austra- lia): Commonwealth Serum Laboratories, [mimeographed]. The present chapter has been devised as a practical guide to serve the Simmons, R.T., D.C. -

Even More Diverse Than We Had Thought: the Multiplicity of Trans-Fly Languages

Language Documentation & Conservation Special Publication No. 5 (December 2012) Melanesian Languages on the Edge of Asia: Challenges for the 21st Century, ed. by Nicholas Evans and Marian Klamer, pp. 109–149 http://nflrc.hawaii.edu/ldc/sp05/ 5 http://hdl.handle.net/10125/4562 Even more diverse than we had thought: The multiplicity of Trans-Fly languages Nicholas Evans Australian National University Linguistically, the Trans Fly region of Southern New Guinea is one of the least known parts of New Guinea. Yet the glimpses we already have are enough to see that it is a zone with among the highest levels of linguistic diversity in New Guinea, arguably only exceeded by those found in the Sepik and the north coast. After surveying the sociocultural setting, in particular the widespread practice of direct sister-exchange which promotes egalitarian multilingualism in the region, I give an initial taste of what its languages are like. I focus on two languages which are neighbours, and whose speakers regularly intermarry, but which belong to two unrelated and typologically distinct families: Nen (Yam Family) and Idi (Pahoturi River Family). I then zoom out to look at some typological features of the whole Trans-Fly region, exemplifying with the dual number category, and close by stressing the need for documentation of the languages of this fascinating region. 1. INTRODUCTION.1 The distribution of linguistic diversity is highly informative, about 1 My thanks to two anonymous referees and to Marian Klamer for their usefully critical comments on an -

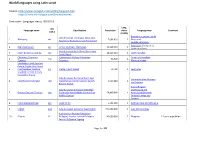

World Languages Using Latin Script

World languages using Latin script Source: http://www.omniglot.com/writing/langalph.htm https://www.ethnologue.com/browse/names Sort order : Language status, ISO 639-3 Lang, ISO Language name Classification Population status Language map Comment 639-3 (EGIDS) Botswana, Lesotho, South Indo-European, Germanic, West, Low 1. Afrikaans, afr 7,096,810 1 Africa and Saxon-Low Franconian, Low Franconian SwazilandNamibia Azerbaijan,Georgia,Iraq 2. Azeri,Azerbaijani azj Turkic, Southern, Azerbaijani 24,226,940 1 Jordan and Syria Indo-European Balto-Slavic Slavic West 3. Czech Bohemian Cestina ces 10,619,340 1 Czech Republic Czech-Slovak Chamorro,Chamorru Austronesian Malayo-Polynesian Guam and Northern 4. cha 94,700 1 Tjamoro Chamorro Mariana Islands Seychelles Creole,Seselwa Creole, Creole, Ilois, Kreol, 5. Kreol Seselwa, Seselwa, crs Creole, French based 72,700 1 Seychelles Seychelles Creole French, Seychellois Creole Indo-European Germanic North East Denmark Finland Norway 6. DanishDansk Rigsdansk dan Scandinavian Danish-Swedish Danish- 5,520,860 1 and Sweden Riksmal Danish AustriaBelgium Indo-European Germanic West High Luxembourg and 7. German Deutsch Tedesco deu German German Middle German East 69,800,000 1 NetherlandsDenmark Middle German Finland Norway and Sweden 8. Estonianestieesti keel ekk Uralic Finnic 1,132,500 1 Estonia Latvia and Lithuania 9. English eng Indo-European Germanic West English 341,000,000 1 over 140 countries Austronesian Malayo-Polynesian 10. Filipino fil Philippine Greater Central Philippine 45,000,000 1 Filippines L2 users population Central Philippine Tagalog Page 1 of 48 World languages using Latin script Lang, ISO Language name Classification Population status Language map Comment 639-3 (EGIDS) Denmark Finland Norway 11. -

LOT Dissertation Series

Cover Page The handle http://hdl.handle.net/1887/25849 holds various files of this Leiden University dissertation. Author: Kluge, Angela Johanna Helene Title: A grammar of Papuan Malay Issue Date: 2014-06-03 1. Introduction Papuan Malay is spoken in West Papua, which covers the western part of the island of New Guinea. This grammar describes Papuan Malay as spoken in the Sarmi area, which is located about 300 km west of Jayapura. Both towns are situated on the northeast coast of West Papua. (See Map 1 on p. xxi and Map 2 on p. xxi.) This chapter provides an introduction to Papuan Malay. The first section (§1.1) gives general background information about the language in terms of its larger geographical and linguistic settings and its speakers. In §1.2, the history of the language is summarized. The classification of Papuan Malay and its dialects are discussed in §1.3, followed in §1.4 by a description of its typological profile and in §1.5 of its sociolinguistic profile. In §1.6, previous research on Papuan Malay is summarized, followed in §1.7 by a brief overview of available materials in Papuan Malay. In §1.8 methodological aspects of the present study are described. 1.1. General information This section presents the geographical and linguistic setting of Papuan Malay and its speakers, and the area where the present research on Papuan Malay was conducted. The geographical setting is described in §1.1.1, and the linguistic setting in §1.1.2. Speaker numbers are discussed in §1.1.3, occupation details in §1.1.4, education and literacy rates in §1.1.5, and religious affiliations in §1.1.6. -

Mark Donohue

Mark Donohue Address: Department of Linguistics, 12 Nelson Place School of Culture, History and Language, Curtin College of Asia and the Pacific, ACT 2605 Coombs Building, Australia Australian National University, ACT 0200, Australia Tel: 0418 644 933 Email: [email protected] URL: http://www.donohue.cc or http://papuan.linguistics.anu.edu.au/Donohue/ or http://asiapacific.anu.edu.au/people/personal/donom_ling.php or https://researchers.anu.edu.au/researchers/donohue-mh Nationality: Australian / British (dual nationality) Languages: Native: English Good: Tukang Besi, Indonesian, Eastern Indonesian non-standard Malay(s), Tok Pisin Intermediate: Dutch, Palu’e, Skou, Japanese, Nepali Basic: One, Mandarin, Cantonese, Iha, Kuke, Kusunda, Bumthang. Academic Positions Language Intelligence, October 2016 ongoing Partner Partner in a consulting firm providing expert advice and applied research in the fields of language, including but not limited to Forensic linguistics, Database assembly, and Typological consulting. Australian National University, June 2015 ongoing Senior Research Fellow, Department of Linguistics, School of Culture, History and Language Continuing research into the linguistic histories in Asia and the Pacific; exploring quantitative methods in comparative linguistics; phonological and tonological analysis. (approximately equal to Associate Research Professor) Australian National University, June 2011 – May 2015 Future Fellow, Department of Linguistics, School of Culture, History and Language (ARC-funded research position) Research into the linguistic macrohistory of Asia and the Pacific; exploring quantitative methods in comparative linguistics; developing testable theories of language contact and language change. Australian National University, January 2011 ongoing Senior Research Fellow, Department of Linguistics, School of Culture, History and Language Continuing research into the linguistic macrohistory of Asia and the Pacific; exploring quantitative methods in comparative linguistics. -

Library of Congress Subject Headings for the Pacific Islands

Library of Congress Subject Headings for the Pacific Islands First compiled by Nancy Sack and Gwen Sinclair Updated by Nancy Sack Current to January 2020 Library of Congress Subject Headings for the Pacific Islands Background An inquiry from a librarian in Micronesia about how to identify subject headings for the Pacific islands highlighted the need for a list of authorized Library of Congress subject headings that are uniquely relevant to the Pacific islands or that are important to the social, economic, or cultural life of the islands. We reasoned that compiling all of the existing subject headings would reveal the extent to which additional subjects may need to be established or updated and we wish to encourage librarians in the Pacific area to contribute new and changed subject headings through the Hawai‘i/Pacific subject headings funnel, coordinated at the University of Hawai‘i at Mānoa.. We captured headings developed for the Pacific, including those for ethnic groups, World War II battles, languages, literatures, place names, traditional religions, etc. Headings for subjects important to the politics, economy, social life, and culture of the Pacific region, such as agricultural products and cultural sites, were also included. Scope Topics related to Australia, New Zealand, and Hawai‘i would predominate in our compilation had they been included. Accordingly, we focused on the Pacific islands in Melanesia, Micronesia, and Polynesia (excluding Hawai‘i and New Zealand). Island groups in other parts of the Pacific were also excluded. References to broader or related terms having no connection with the Pacific were not included. Overview This compilation is modeled on similar publications such as Music Subject Headings: Compiled from Library of Congress Subject Headings and Library of Congress Subject Headings in Jewish Studies. -

A Grammar and Dictionary of the Malay Language

Oa^i«^/Vii^j. ( .(fc GRAMMAR AND DICTIONARY MALAY LANGUAGE. : GRAMMAR AND DICTIONARY MALAY LANGUAG?:, A PRELIMINARY DISSERTATION, JOHN CEAWFUED, F.R.S. Author of "The History of the Indian Archipelago." IN TWO VOLUMES. VOL. I. DISSERTATION AND GRAMMAR. LONDON SMITH, ELDER, AND CO., 65, CORNHILL. 1852. : LONDON nRADBURY AND EVANS, PRINTERS, WHITBFTtlAR». THE BARON ALEXANDER VON HUMBOLDT Sib, I dedicate this "Work to you, on account of the high respect which, in common with tlie rest of the world, I entertain for yourself; and in testimony of my veneration for your distinguished brother, whose correspondence on the subject of my labours I hold in grateful recoUectiou. I am, with great esteem, Your faithful Servant, J. CRAWFURD. PREFACE. The Work which I now submit to the Public is the result of much labour, spread, with various interruptions, over a period of more than forty years, twelve of which were passed in countries of which the Malay is the vernacular or the popular language, and ten in the compilation of materials. It remains for me only to acknowledge my obligations to those who assisted me in the compilation of my book. ]My first and greatest are to my friend and predecessor in the same field of labour, the late William INIarsden, the judicious and learned author of the History of Sumatra, and of the Malay Grammar and Dictionary. A few months before his death, Mr. Marsden delivered to me a copy of his Dictionary, corrected with his own hand, and two valuable lists of words, with which he had been furnished by the Rev. -

West Irian Bibliography (1984

Papuaweb's searchable full-text version of West Irian: A Bibliography by van Baal, Galis, Koentjaraningrat (1984) This document is made available via www.papuaweb.org and reproduced with the kind permission of the Koninklijk Instituut voor Taal-, Land- en Volkenkunde, The Netherlands (www.kitlv.nl) with all rights reserved, 2005. This is an automatically generated PDF document interpolated from a high-resolution scan (600dpi) of the original text. This document was not proof-read for errors in content or formatting. Papuaweb may eventually prepare a corrected full-text version of this document subject to available project resources and the priorities of website users. For an error-free digital facsimile of this document (image-based PDF) see http://www.papuaweb.org/dlib/bk1/kitlv/bib/450dpi.pdf (19Mb). KONINKLIJK INSTITUUT VOOR TAAL-, LAND- EN VOLKENKUNDE BIBLIOGRAPHICAL SERIES 15 J. VAN BAAL, K.W. GALIS and R.M. KOENTJARANINGRAT WEST IRIAN A BIBLIOGRAPHY 1984 FORIS PUBLICATIONS Dordrecht-Holland/Cinnaminson-U.S.A. Published by: Foris Publications Holland P.O. Box 509 3300 AM Dordrecht, The Netherlands Sole distributor for the U.S.A. and Canada: Foris Publications U.S.A. P.O. Box C-50 Cinnaminson N J. 08077 CONTENTS U.S.A. Preface Abbreviations XIII / General 1.1. General Works 1.2. Bibliographies, Serials and Periodicals 1.2.1. Bibliographies 1.2.2. Serials and Periodicals 1.3. Maps 1.4. Bibliography // Climate, Geology, and Soils 11.1. Climate 9 11.2. Geology 10 11.2.1. Introduction 10 11.2.2. General Works 11 11.2.3. Geological exploration 11 11.3.