Killer Corsairs How the Navy Got Them in Line

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Following Are Edited Excerpts from Two Interviews Conducted with Dr

Interviews with Dr. Wernher von Braun Editor's note: The following are edited excerpts from two interviews conducted with Dr. Wernher von Braun. Interview #1 was conducted on August 25, 1970, by Robert Sherrod while Dr. von Braun was deputy associate administrator for planning at NASA Headquarters. Interview #2 was conducted on November 17, 1971, by Roger Bilstein and John Beltz. These interviews are among those published in Before This Decade is Out: Personal Reflections on the Apollo Program, (SP-4223, 1999) edited by Glen E. Swanson, whick is vailable on-line at http://history.nasa.gov/SP-4223/sp4223.htm on the Web. Interview #1 In the Apollo Spacecraft Chronology, you are quoted as saying "It is true that for a long time we were not in favor of lunar orbit rendezvous. We favored Earth orbit rendezvous." Well, actually even that is not quite correct, because at the outset we just didn't know which route [for Apollo to travel to the Moon] was the most promising. We made an agreement with Houston that we at Marshall would concentrate on the study of Earth orbit rendezvous, but that did not mean we wanted to sell it as our preferred scheme. We weren't ready to vote for it yet; our study was meant to merely identify the problems involved. The agreement also said that Houston would concentrate on studying the lunar rendezvous mode. Only after both groups had done their homework would we compare notes. This agreement was based on common sense. You don't start selling your scheme until you are convinced that it is superior. -

Apollo 13 Mission Review

APOLLO 13 MISSION REVIEW HEAR& BEFORE THE COMMITTEE ON AERONAUTICAL AND SPACE SCIENCES UNITED STATES SENATE NINETY-FIRST CONGRESS SECOR’D SESSION JUR’E 30, 1970 Printed for the use of the Committee on Aeronautical and Space Sciences U.S. GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE 47476 0 WASHINGTON : 1970 COMMITTEE ON AEROKAUTICAL AND SPACE SCIENCES CLINTON P. ANDERSON, New Mexico, Chairman RICHARD B. RUSSELL, Georgia MARGARET CHASE SMITH, Maine WARREN G. MAGNUSON, Washington CARL T. CURTIS, Nebraska STUART SYMINGTON, bfissouri MARK 0. HATFIELD, Oregon JOHN STENNIS, Mississippi BARRY GOLDWATER, Arizona STEPHEN M.YOUNG, Ohio WILLIAM B. SAXBE, Ohio THOJfAS J. DODD, Connecticut RALPH T. SMITH, Illinois HOWARD W. CANNON, Nevada SPESSARD L. HOLLAND, Florida J4MES J. GEHRIG,Stad Director EVERARDH. SMITH, Jr., Professional staffMember Dr. GLENP. WILSOS,Professional #tad Member CRAIGVOORHEES, Professional Staff Nember WILLIAMPARKER, Professional Staff Member SAMBOUCHARD, Assistant Chief Clerk DONALDH. BRESNAS,Research Assistant (11) CONTENTS Tuesday, June 30, 1970 : Page Opening statement by the chairman, Senator Clinton P. Anderson-__- 1 Review Board Findings, Determinations and Recommendations-----_ 2 Testimony of- Dr. Thomas 0. Paine, Administrator of NASA, accompanied by Edgar M. Cortright, Director, Langley Research Center and Chairman of the dpollo 13 Review Board ; Dr. Charles D. Har- rington, Chairman, Aerospace Safety Advisory Panel ; Dr. Dale D. Myers, Associate Administrator for Manned Space Flight, and Dr. Rocco A. Petrone, hpollo Director -___________ 21, 30 Edgar 11. Cortright, Chairman, hpollo 13 Review Board-------- 21,27 Dr. Dale D. Mvers. Associate Administrator for Manned SDace 68 69 105 109 LIST OF ILLUSTRATIOSS 1. Internal coinponents of oxygen tank So. 2 ---_____-_________________ 22 2. -

Apollo Over the Moon: a View from Orbit (Nasa Sp-362)

chl APOLLO OVER THE MOON: A VIEW FROM ORBIT (NASA SP-362) Chapter 1 - Introduction Harold Masursky, Farouk El-Baz, Frederick J. Doyle, and Leon J. Kosofsky [For a high resolution picture- click here] Objectives [1] Photography of the lunar surface was considered an important goal of the Apollo program by the National Aeronautics and Space Administration. The important objectives of Apollo photography were (1) to gather data pertaining to the topography and specific landmarks along the approach paths to the early Apollo landing sites; (2) to obtain high-resolution photographs of the landing sites and surrounding areas to plan lunar surface exploration, and to provide a basis for extrapolating the concentrated observations at the landing sites to nearby areas; and (3) to obtain photographs suitable for regional studies of the lunar geologic environment and the processes that act upon it. Through study of the photographs and all other arrays of information gathered by the Apollo and earlier lunar programs, we may develop an understanding of the evolution of the lunar crust. In this introductory chapter we describe how the Apollo photographic systems were selected and used; how the photographic mission plans were formulated and conducted; how part of the great mass of data is being analyzed and published; and, finally, we describe some of the scientific results. Historically most lunar atlases have used photointerpretive techniques to discuss the possible origins of the Moon's crust and its surface features. The ideas presented in this volume also rely on photointerpretation. However, many ideas are substantiated or expanded by information obtained from the huge arrays of supporting data gathered by Earth-based and orbital sensors, from experiments deployed on the lunar surface, and from studies made of the returned samples. -

Challenger Accident in a Rogers Commission Hearing at KSC

CHALLENGER By Arnold D. Aldrich Former Program Director, NSTS August 27, 2008 Recently, I was asked by John Shannon, the current Space Shuttle Program Manager, to comment on my experiences, best practices, and lessons learned as a former Space Shuttle program manager. This project is part of a broader knowledge capture and retention initiative being conducted by the NASA Johnson Space Center in an “oral history” format. One of the questions posed was to comment on some of the most memorable moments of my time as a Space Shuttle program manager. Without question, the top two of these were the launch of Challenger on STS‐51L on January 28, 1986, and the launch of Discovery on STS‐26 on September 29, 1988. Background The tragic launch and loss of Challenger occurred over 22 years ago. 73 seconds into flight the right hand Solid Rocket Booster (SRB) broke away from the External Tank (ET) as a result of a burn‐ through in its aft most case to case joint and the Space Shuttle vehicle disintegrated resulting in the total loss of the vehicle and crew. The events leading up to that launch are still vivid in my mind and deeply trouble me to this day, as I know they always will. This paper is not about what occurred during the countdown leading up to the launch – those facts and events were thoroughly investigated and documented by the Rogers Commission. Rather, what I can never come to closure with is how we, as a launch team, and I, as one of the leaders of that team, allowed the launch to occur. -

Nasa Johnson Space Center Oral History Project Oral History Transcript

NASA JOHNSON SPACE CENTER ORAL HISTORY PROJECT ORAL HISTORY TRANSCRIPT FAROUK EL-BAZ INTERVIEWED BY REBECCA WRIGHT BOSTON, MASSACHUSETTS – NOVEMBER 2, 2009 WRIGHT: Today is November 2, 2009. This oral history interview is being conducted with Dr. Farouk El-Baz in Boston, Massachusetts, for the Johnson Space Center Oral History Project. Interviewer is Rebecca Wright, assisted by Jennifer Ross-Nazzal. We certainly would like to start by telling you thank you. We know you‘re a very busy person with a very busy schedule, so thank you for finding time for us today. EL-BAZ: You‘re welcome to come here, because this is part of the history of the United States. It‘s important that we all chip in. WRIGHT: We‘re glad to hear that. We know your work with NASA began as early as 1967 when you became employed by Bellcomm [Incorporated]. Could you share with us how you learned about that opportunity and how you made that transition into becoming an employee there? EL-BAZ: Just the backdrop, I finished my PhD here in the US. First job offer was from Germany. It was in June 1964; I was teaching there [at the University of Heidelberg] until December 1965. I went to Egypt then, tried to get a job in geology. I was unable for a whole year, so I came back to the US as an immigrant in the end of 1966. For the first three months of 1967, I began to search for a job. When I arrived in the winter, most of the people that I knew 2 November 2009 1 Johnson Space Center Oral History Project Farouk El-Baz were at universities, and most universities had hired the people that would teach during the year. -

Spacewalk Database

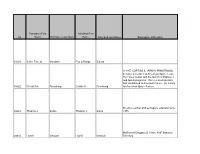

Purchaser First Inscribed First ID Name Purchaser Last Name Name Inscribed Last Name Biographic_Infomation 01558 Beth / Forrest Goodwin Ron & Margo Borrup In 1957 CURTISS S. (ARMY) ARMSTRONG became a member of America's Space Team. His career began with the launch of Explorer I and Apollo programs. His tireless dedication has contributed to America's future. He is truly 00022 Cheryl Ann Armstrong Curtiss S. Armstrong an American Space Pioneer. Science teacher and aerospace educator since 00023 Thomas J. Sarko Thomas J. Sarko 1975. McDonnell Douglas 25 Years, AMF Board of 00024 Lowell Grissom Lowell Grissom Directors Joined KSC in 1962 in the Director's Protocol Office. Responsible for the meticulous details for the arrival, lodging, and banquets for Kings, Queens and other VIP worldwide and their comprehensive tours of KSC with top KSC 00025 Major Jay M. Viehman Jay Merle Viehman Personnel briefing at each poi WWII US Army Air Force 1st Lt. 1943-1946. US Civil Service 1946-1972 Engineer. US Army Ballistic Missile Launch Operations. Redstone, Jupiter, Pershing. 1st Satellite (US), Mercury 1st Flight Saturn, Lunar Landing. Retired 1972 from 00026 Robert F. Heiser Robert F. Heiser NASA John F. Kennedy S Involved in Air Force, NASA, National and Commercial Space Programs since 1959. Commander Air Force Space Division 1983 to 1986. Director Kennedy Space Center - 1986 to 1 Jan 1992. Vice President, Lockheed Martin 00027 Gen. Forrest S. McCartney Forrest S. McCartney Launch Operations. Involved in the operations of the first 41 manned missions. Twenty years with NASA. Ten years 00028 Paul C. Donnelly Paul C. -

Building for the Future

The Space Congress® Proceedings 1983 (20th) Space: The Next Twenty Years Apr 1st, 8:00 AM Building for the Future Rocco Petrone Assistant Director for Program Management, Kennedy Space Center, NASA Follow this and additional works at: https://commons.erau.edu/space-congress-proceedings Scholarly Commons Citation Petrone, Rocco, "Building for the Future" (1983). The Space Congress® Proceedings. 3. https://commons.erau.edu/space-congress-proceedings/proceedings-1983-20th/session-iv/3 This Event is brought to you for free and open access by the Conferences at Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in The Space Congress® Proceedings by an authorized administrator of Scholarly Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. "Building for the Future" First Space Congress Lt. Col. Rocco Petrone Assistant Director for Program Management Kennedy Space Center, NASA April 20, 1964 Thank you, Mr. Hagan: It is an honor and a challenge for me to speak to this distinguished gruup representing the space community and to undertake an extremely ditiicult task - which is to attempt to substitute for Dr. Kurt Debus, Director oi the John F. Kennedy Space Center, NASA. Dr. Debus asked me to extend his sincere regrets. You may know that Mrs. Debus recently underwent major surgery in Nashville. While she is recuperating nicely, Dr. Debus could not speak to you at this time. Let me add a hearty welcome from NASA to that of John Hagan, the Canaveral Council of Technical Societies, and General Davis. It is very appropriate, of course, that the First Space Congress has convened at the door of the nation 1 s spaceport. -

1967 Spaceport News Summary

1967 Spaceport News Summary Followup From the Last Spaceport News Summary Of note, the 1963, 1964 and 1965 Spaceport News were issued weekly. Starting with the July 7, 1966, issue, the Spaceport News went to an every two week format. The Spaceport News kept the two week format until the last issue on February 24, 2014. Spaceport Magazine superseded the Spaceport News in April 2014. Spaceport Magazine was a monthly issue, until the last and final issue, Jan./Feb. 2020. The first issue of Spaceport News was December 13, 1962. The two 1962 issues and the issues from 1996 forward are at this website, including the Spaceport Magazine. All links were working at the time I completed this Spaceport News Summary. In the March 3, 1966, Spaceport News, there was an article about tool cribs. The Spaceport News article mentioned “…“THE FIRST of 10 tool cribs to be installed and operated at Launch Complex 39 has opened…”. The photo from the article is below. Page 1 Today, Material Service Center 31 is on the 1st floor of the VAB, on the K, L side (west side) of the building. If there were 10 tool cribs, as mentioned in the 1966 article, does anyone know the story behind the numbering scheme? Tool crib #75? From The January 6, 1967, Spaceport News From page 1, “Launch Team Personnel Named”. A portion of the article reads “Key launch team personnel for the manned flight of Apollo/Saturn 204 have been announced. The 204 mission, to be launched from KSC’s Complex 34, will be the first in which astronauts will fly the three-man Apollo spacecraft. -

THE WACO, TEXAS, ATF RAID and CHALLENGER LAUNCH DECISION Management, Judgment, and the Knowledge Analytic

ARPAGarrett / / March ATF RAID 2001 AND CHALLENGER DECISION THE WACO, TEXAS, ATF RAID AND CHALLENGER LAUNCH DECISION Management, Judgment, and the Knowledge Analytic TERENCE M. GARRETT University of Texas Pan American The author argues that the Challenger space shuttle launch disaster and the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco and Firearms (ATF) raid on the Branch Davidian compound both offer insights for managers and orga- nization theorists as to how managers make judgments concerning their employees based on concep- tions of how the employees ought to do their work. Managers with a knowledge of “management as sci- ence” objectify the work of employees under them. Workers know their work as craft based on firsthand experience. The author argues that traditional management practice results in decision making that does not take into account the knowledge of all organizational participants, and this leads to catastro- phe. “Worker” knowledge and “management” knowledge, as well as other kinds of knowledge in orga- nizations, are frequently incompatible. This aspect is characteristic of modern organizations but tends to be accentuated during times of organizational crisis. These two cases illustrate well the problems involved in decision making within complex organizations. The Challenger space shuttle launch of January 28, 1986, and the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco and Firearms (ATF) raid in Waco, Texas, on February 28, 1993, are two infamous cases where managers made decisions that resulted in death and destruction in an arguably unnecessary fashion. To come to an understanding con- cerning the management practices of the Waco/ATF raid and Challenger launch decision case studies, I will apply Carnevale and Hummel’s “knowledge analytic.”1 In short, the knowledge analytic is concerned with multiple knowledges in modern organizations: 1. -

DOC.NO--Moo"" John F

APOLLQ 5 POST-LAUNCH PRESS CONFERENCE SATURN HISTORY DOCUMENT Univeoityof Alabama Research Institute History of Science G. Technology G~UP $. -,-7. ' Press Site #2 --- ----..-DOC.NO--moo"" John F. Kennedy Space Center National Aeronautics and Space Adrr;inistGijon Monday, January 22, 1968 Major Gci12raI Samuel C. Pllillips, Director, &polio Program Office, Office of Manrred Space iqki, Fl - - NASA Rocco A. Pettone, Director of Laanch Oyoetions, Kennedy Space Center, NASA Colonel Will ian Teir, Manager, Saturn I/iB Program Office, Marsha!! Space Flig!?: Ccnier, NASA Mr. King: The gentlemen from my right, Bill Teir, who is the Saturn IB Project Manager from the Marshall Space flight Center; General Sam Phillips, who is the Apollo Program Manager, Gffice of Manned Space Flight, NASA Headq~rarters; Rocco Petrone, who is Director of Launch Opesa- tions for Kennedy Space Center, also Launch Director for the mission. General Phillips. Gen. Phil lips: Ladies and gentlemen, it's a pleasure to be back hare again. Apollo 5 was successfully launched at 5:48:08 Eastern Standard Time. The performance of the launch vehicle, in terms of the times of the burns, was completely nominal and you can foll~wthe time lines as they were given in the press kit. The shutdown of the S-IVE occurred on time at 9:58 after the launch and orbital insertion was at 10:08. The orbit planned war; 88 by 118, The actual orbit was 87.6 by 119.5. The velocity at orbital insertion was 25,685 feet per second. The sequence, up until the time we left the Flight Director's circuit a few minutes ago, had taken us oiler Carnarvon, where the deployment of the Spacecraft LM Adapter panels was confirmed and the sequence that, was the separation of the Lunar Modtile f.r.oro the booster occurred and was confirmed. -

Nasa's Exploration Initiative: Status and Issues Hearing Committee on Science and Technology House of Representatives

NASA’S EXPLORATION INITIATIVE: STATUS AND ISSUES HEARING BEFORE THE SUBCOMMITTEE ON SPACE AND AERONAUTICS COMMITTEE ON SCIENCE AND TECHNOLOGY HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES ONE HUNDRED TENTH CONGRESS SECOND SESSION APRIL 3, 2008 Serial No. 110–90 Printed for the use of the Committee on Science and Technology ( Available via the World Wide Web: http://www.science.house.gov U.S. GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE 41–471PS WASHINGTON : 2008 For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office Internet: bookstore.gpo.gov Phone: toll free (866) 512–1800; DC area (202) 512–1800 Fax: (202) 512–2104 Mail: Stop IDCC, Washington, DC 20402–0001 VerDate 11-MAY-2000 11:02 Aug 02, 2008 Jkt 041471 PO 00000 Frm 00001 Fmt 5011 Sfmt 5011 C:\WORKD\SA08\040308\41471 SCIENCE1 PsN: SCIENCE1 COMMITTEE ON SCIENCE AND TECHNOLOGY HON. BART GORDON, Tennessee, Chairman JERRY F. COSTELLO, Illinois RALPH M. HALL, Texas EDDIE BERNICE JOHNSON, Texas F. JAMES SENSENBRENNER JR., LYNN C. WOOLSEY, California Wisconsin MARK UDALL, Colorado LAMAR S. SMITH, Texas DAVID WU, Oregon DANA ROHRABACHER, California BRIAN BAIRD, Washington ROSCOE G. BARTLETT, Maryland BRAD MILLER, North Carolina VERNON J. EHLERS, Michigan DANIEL LIPINSKI, Illinois FRANK D. LUCAS, Oklahoma NICK LAMPSON, Texas JUDY BIGGERT, Illinois GABRIELLE GIFFORDS, Arizona W. TODD AKIN, Missouri JERRY MCNERNEY, California JO BONNER, Alabama LAURA RICHARDSON, California TOM FEENEY, Florida PAUL KANJORSKI, Pennsylvania RANDY NEUGEBAUER, Texas DARLENE HOOLEY, Oregon BOB INGLIS, South Carolina STEVEN R. ROTHMAN, New Jersey DAVID G. REICHERT, Washington JIM MATHESON, Utah MICHAEL T. MCCAUL, Texas MIKE ROSS, Arkansas MARIO DIAZ-BALART, Florida BEN CHANDLER, Kentucky PHIL GINGREY, Georgia RUSS CARNAHAN, Missouri BRIAN P. -

+ Sept. 15, 2006

September 15, 2006 Vol. 45, No. 18 Spaceport News John F. Kennedy Space Center - America’s gateway to the universe http://www.nasa.gov/centers/kennedy/news/snews/spnews_toc.html Atlantis, STS-115 return to space station construction Landing scheduled delayed previous attempts. “It’s been almost four years, for Sept. 20 at KSC two return-to-flight missions, a tremendous amount of work by oments before the launch thousands of individuals to get the of Space Shuttle Atlantis shuttle program back to where we Mon STS-115, Commander are right now and that’s on the Brent Jett expressed the crew’s verge of restarting the station excitement about the mission from assembly sequence,” Jett said. his seat inside the orbiter. The fuel cut-off sensor system, “We’re confident over the next which delayed Atlantis’ scheduled few weeks, and few years for that Sept. 8 launch, performed normally matter, that NASA’s going to prove the following day. The engine cut- to our nation, to our partners and off sensor is one of four inside the our friends around the world that it liquid hydrogen section of the was worth the wait and the shuttle’s external fuel tank. sacrifice,” Jett said. “We’re ready Atlantis’ flight resumes to get to work.” construction of the station. The Atlantis and its six-member shuttle and station crews will work crew are docked at the Interna- with ground teams to install a tional Space Station after lifting girder-like structure, known as the off from Kennedy Space Center at P3/P4 truss, aboard the station.