Primary-Source-Documents.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Matilda Joslyn Gage: Writing and “Righting” the History of Woman

20 MATILDA JOSLYN GAGE FOUNDATION FOUNDATION GAGE JOSLYN MATILDA Writing and Matilda the NWSA’s most active years and those spent writing the History.Volume IV minimized Gage’s activism and her contri- Joslyn bution to the History.For this reason, modern historians who have relied on Volume IV’s description of her work have Gage also tended to minimize Gage’s Gage’s role in that work alone contribution. BY MARY E. COREY should have guaranteed her a The rift between Gage and place of honor in our collective Anthony had its roots in the memory of the suffrage past. circumstances surrounding the Through a grand historic irony, one of Instead, it has obscured her formation of the NWSA in 1869. part in this and other move- Immediately following the the women most instrumental in the ment histories. Civil War, the reform alliance Volumes I, II, and III preserved between abolitionists and preservation of woman suffrage history the work of the National women’s rights advocates has herself been largely overlooked in Woman Suffrage Association crumbled in the fierce in-fight- from the beginnings of the ing over suffrage priorities. the histories of this movement. movement to about 1883. Unable to prevail on the issue Gage’s contributions to these of suffrage, Stanton, Anthony, Matilda Joslyn Gage was three volumes cannot be and Gage left the final American one of three National Woman overestimated. Her essays, Equal Rights Association Suffrage Association (NWSA) “Preceding Causes,”“Woman, Convention in May 1869 and founders who were known to Church and State,” and held an impromptu evening their contemporaries as the “Woman’s Patriotism in the War” session. -

The Woman-Slave Analogy: Rhetorical Foundations in American

The Woman-Slave Analogy: Rhetorical Foundations in American Culture, 1830-1900 Ana Lucette Stevenson BComm (dist.), BA (HonsI) A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy at The University of Queensland in 2014 School of History, Philosophy, Religion and Classics I Abstract During the 1830s, Sarah Grimké, the abolitionist and women’s rights reformer from South Carolina, stated: “It was when my soul was deeply moved at the wrongs of the slave that I first perceived distinctly the subject condition of women.” This rhetorical comparison between women and slaves – the woman-slave analogy – emerged in Europe during the seventeenth century, but gained peculiar significance in the United States during the nineteenth century. This rhetoric was inspired by the Revolutionary Era language of liberty versus tyranny, and discourses of slavery gained prominence in the reform culture that was dominated by the American antislavery movement and shared among the sisterhood of reforms. The woman-slave analogy functioned on the idea that the position of women was no better – nor any freer – than slaves. It was used to critique the exclusion of women from a national body politic based on the concept that “all men are created equal.” From the 1830s onwards, this analogy came to permeate the rhetorical practices of social reformers, especially those involved in the antislavery, women’s rights, dress reform, suffrage and labour movements. Sarah’s sister, Angelina, asked: “Can you not see that women could do, and would do a hundred times more for the slave if she were not fettered?” My thesis explores manifestations of the woman-slave analogy through the themes of marriage, fashion, politics, labour, and sex. -

200128 Centre for the Study of Race and Racism

LONDON’S GLOBAL UNIVERSITY Buildings Naming and Renaming Committee Request for naming Proposal Please set out details of the room / building / equipment or other entity that you wish to propose a name / for, and indicate additionally whether a) this is a naming proposal associated with a philanthropic donation b) you are proposing to name a building or other entity in honour of a deceased staff member or student This is not a philanthropic donation. I am proposing to name the centre after a deceased former student. I propose that we name UCL’s new multi-disciplinary centre for the study of race and racism after Sarah Parker Remond (1826-1894). She meets the circulated criteria under which UCL honours individuals for their exceptional achievements, and I have no doubt that her image and example will inspire those who use the Centre’s facilities and contribute to its mission. Remond was a free-born African American radical, suffragist, anti-slavery activist and later, a physician. She moved to England in 1859 and, as a notable and effective abolitionist campaigner, was the first woman to lecture publicly against slavery in this country. Eventually, she settled in London’s Holland Park where she became active in a range of radical social movements. Remond studied languages and liberal arts at Bedford College before changing direction sharply and enrolling at London University College from where she graduated as a nurse in 1865. She relocated to Italy in 1866 and completed her training as a doctor of medicine in Florence at the Santa Maria Nuova hospital school in 1871. -

CAMBRIDGE SUFFRAGE HISTORY CAMBRIDGE SUFFRAGE HISTORY a Long March for Suffrage

CAMBRIDGE SUFFRAGE HISTORY CAMBRIDGE SUFFRAGE HISTORY A long march for suffrage. Margaret Fuller was born in Cambridge in1810. By her late teens, she was considered a prodigy and equal or superior in intelligence to her male friends. As an adult she hosted “Conversations” for men and women on topics that ranged from women’s rights to philosophy. She joined Ralph Waldo Emerson in editing and writing for the Transcendentalist journal, The Dial from 1840-1842. It was in this publication that she wrote an article about women’s rights titled, “The Great Lawsuit,” which she would go on to expand into a book a few years later. In 1844, she moved to NYC to write for the New York Tribune. Her book, Woman in the Nineteenth Century was published in1845. She traveled to Europe as the Tribune’s foreign correspondent, the first woman to hold such a role. She died in a shipwreck off the coast of NY in July 1850 just as she was returning to life in the U.S. Her husband and infant also perished. It was hoped that she would be a leader in the equal rights and suffrage movements but her life was tragically cut short. 02 SARAH BURKS, CAMBRIDGE HISTORICAL COMMISSION December 2019 CAMBRIDGE SUFFRAGE HISTORY A long march for suffrage. Harriet A. Jacobs (1813-1897) was born into slavery in Edenton, NC. She escaped her sexually abusive owner in 1835 and lived in hiding for seven years. In 1842 she escaped to the north. She eventually was able to secure freedom for her children and herself. -

Training Video #1 - How Married Couples Learn to Be Sponsors/Mentors

Training Video #1 - How married couples learn to be sponsors/mentors. If you are a marriage educator, adapt these ideas to your situation. INTRODUCTION THE VIDEO and ADDITIONAL RESOURCES WHAT IS A "SPONSOR COUPLE" AND WHAT DO THEY DO? HOW DO YOU KNOW WHETHER YOU CAN DO THIS? THE DESIGN OF THE PROGRAM PREPARING YOURSELVES…BEFORE YOU MEET WITH AN ENGAGED COUPLE LEARNING TO USE EACH OTHER’S STRENGTHS DECIDING WHERE TO MEET MINIMIZING DISTRACTIONS SNACKS & BREAKS PRAYER DEALING WITH QUESTIONS SCHEDULING THE SESSIONS FIRST SESSION THE FOUR RULES INTRODUCING THE CANDLE AND PRAYER DIALGOGUE / DISCUSSION WITH THE ENGAGED COUPLE DEALING WITH UNEXPECTED CHALLENGES RESOURCES A TYPICAL SESSION WITH THE ENGAGED FOLLOW UP CONCLUSION OF VIDEO ONE INTRODUCTION [TRAINER: So, if you are here today because you think have the “perfect marriage,” I would say that you are the one couple I would encourage to find another ministry. You need to be a “normally nutty” couple to able to help those just beginning the journey of Christian marriage. While these books (For Better and For Ever) provide really good information, it is your own life experience through the good times and terrible times of marriage that will help engaged couples learn to survive and grow as married couples. People getting married today are scared that they might not be successful. It does not help them to meet “the perfect couple.” They need to know that normal “nutty” couples …like them…can survive the challenges of marriage. ] NARRATOR: Welcome to the ministry of marriage preparation. · The task of the church is to teach people how to live the gospel of Jesus. -

The Second National Woman's Rights Convention Worcester, MA October

Handout 2C The Second National Woman’s Rights Convention Worcester, MA October 15-16, 1851 One year after the first national convention, Worcester played host to the second national women’s rights convention. The second convention had been planned during the first and Mrs. Paulina W. Davis served as president pro tempore once more. Like the first convention, this meeting addressed more than just women’s suffrage, but other women’s rights issues as well, including education, job training, and the need for more women in the medical field. There were eight committees in total: the Finance Committee, the Business Committee, the Central Committee, the Educational Committee, the Industrial Committee, the Committee on Civil and Political Functions, the Committee on Social Relations, and the Committee on Publications. Many Massachusetts women served on these committees, including Sarah H. Earle, Abby Kelly Foster, Abby H. Price, Harriet K. Hunt, Anna Q.T. Parsons, Lucy Stone, Eliza H. Taft, Augustine C. Taft, Eliza A. Stowell, and Eliza Blarney. As president pro tempore, Davis gave an opening address yet again. She noted that at this point, the women’s rights movement had gained much attention, remarkable given that it had only been a year since the first national convention. She did recognize the opposition to the movement, though, yet proudly stated: There remains no doubt now that the discussions of our Conventions and their published proceedings have aroused, in some degree, that sort of inquiry into our doctrine of human rights which it demands. I have said Human Rights, not Woman’s Rights, for the relations, wants, duties, and rights of the sexes center upon the same great truth, and are logically, as they are practically, inseparable.1 Davis noted other examples of success, including the new schools that have been opened 1 “The proceedings of the Woman’s Rights Convention, held at Worcester, October 15th and 16th, 1851. -

Pdf, 147.07 KB

The crew visits the lush FOREST MOON OF GRENLYND and find that shrinking down just makes bigger problems. DAR pulls a PLECK. A marriage is consummated. [Dramatic science-fiction music plays, like the text crawl at the beginning of Star Wars] NARRATOR: The period of civil war has ended. The rebels have defeated the evil Galactic Monarchy and established the harmonious Federated Alliance. Now, ambassador Pleck Decksetter and his intrepid crew travel the farthest reaches of the galaxy to explore astounding new worlds, discover their heroic destinies, and meet weird bug creatures and stuff. This is [echoing] Mission to Zyxx! [Music becomes more dramatic and trumpet-y, then fades away] PLECK: Hey, Dar? DAR: Yeah, what’s up? PLECK: Um-- [quietly] Can I ask you, like, a personal question? DAR: No. PLECK: Okay. [pause] Hey, C-53? C-53: [whirrs as if turning to face Pleck] Yes? PLECK: What species is Dar? C-53: Ambassador Decksetter, I believe you just asked Dar whether you could ask her a personal question. PLECK: [very quietly] You don’t need-- you can just keep quiet-- C-53: And she responded in the negative. PLECK: Okay. That’s-- yep. C-53: I would feel I was invading her privacy to reveal that information. PLECK: Okay, yeah. No, we don’t need to talk-- I get that now. We don’t need to talk-- I was just curious. C-53: Very well. PLECK: [clears throat] Hey, Bargie? BARGIE: No. PLECK: [laughs] No, I’m not gonna-- I would not-- I get it, we’re not, I’m-- C-53: [moderately amused] But were you about to ask? PLECK: That doesn’t-- that’s irrelevant at this point. -

The 19Th Amendment

National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior Women Making History: The 19th Amendment Women The right of citizens of the United States to vote shall not be denied or abridged by the United States or by any State on account of sex. Congress shall have power to enforce this article by appropriate legislation. —19th Amendment to the United States Constitution In 1920, after decades of tireless activism by countless determined suffragists, American women were finally guaranteed the right to vote. The year 2020 marks the 100th anniversary of the 19th Amendment. It was ratified by the states on August 18, 1920 and certified as an amendment to the US Constitution on August 26, 1920. Developed in partnership with the National Park Service, this publication weaves together multiple stories about the quest for women’s suffrage across the country, including those who opposed it, the role of allies and other civil rights movements, who was left behind, and how the battle differed in communities across the United States. Explore the complex history and pivotal moments that led to ratification of the 19th Amendment as well as the places where that history happened and its continued impact today. 0-31857-0 Cover Barcode-Arial.pdf 1 2/17/20 1:58 PM $14.95 ISBN 978-1-68184-267-7 51495 9 781681 842677 The National Park Service is a bureau within the Department Front cover: League of Women Voters poster, 1920. of the Interior. It preserves unimpaired the natural and Back cover: Mary B. Talbert, ca. 1901. cultural resources and values of the National Park System for the enjoyment, education, and inspiration of this and All rights reserved, including the right to reproduce this work future generations. -

Fall 2013 Fall 2013

W ORCESTER W OMEN’S H ISTORY P ROJECT We remember our past . to better shape our future. WWHP VOL.WWHP 13, VOLUME NO. 2 13, NO. 2 FALL 2013 FALL 2013 WWHP and the Intergenerational Urban Institute at NOTICE Worcester State University are pleased to OF present 18th ANNUAL MEETING Michèle LaRue Thursday, October 24, 2013 in 5:30 p.m. Someone Must Wash the Dishes: Worcester Historical Museum followed by a talk by An Anti-Suffrage Satire Karen Board Moran Many women fought against getting the vote in the early 1900s, on her new book but none with more charm, prettier clothes—and less logic— than the fictional speaker in this satiric monologue written by Gates Along My Path pro-suffragist Marie Jenney Howe, back in 1912. “Woman suf- Booksigning frage is the reform against nature,” declares Howe’s unlikely, but irresistibly likeable, heroine. Light Refreshments “Ladies, get what you want. Pound pillows. Make a scene. Photo by Ken Smith of Quiet Heart Images Make home a hell on earth—but do it in a womanly way! That is All Welcome so much more dignified and refined than walking up to a ballot box and dropping in a piece of paper!” See page 3 for details. Reviewers have called this production “wicked” in its wit, and have labeled Michèle LaRue’s performance "side-splitting." An Illinois native, now based in New York, LaRue is a professional actress who tours nationally with a repertoire of shows by turn-of-the- previous-century American writers. Panel Discussion follows on the unfinished business of women’s rights. -

Information to Users

INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand corner and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. Each original is also photographed in one exposure and is included in reduced form at the back of the book. Photographs included in the original manuscript have been reproduced xerographically in this copy. Higher quality 6" x 9" black and white photographic prints are available for any photographs or illustrations appearing in this copy for an additional charge. Contact UMI directly to order. University Microfilms International A Bell & Howell Information Company 300 North Zeeb Road. Ann Arbor. Ml 48106-1346 USA 313/761-4700 800/521-0600 Order Number 1345736 Musicals often demonstrate the cultural aspects of the periods in which they were written Dowd, James M., M.A. The American University, 1991 Copyright ©1991 by Dowd, James M. -

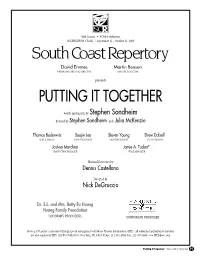

Putting It Together

46th Season • 437th Production SEGERSTROM STAGE / September 11 - October 11, 2009 David Emmes Martin Benson Producing ArtiStic director ArtiStic director presents PUTTING IT TOGETHER words and music by Stephen Sondheim devised by Stephen Sondheim and Julia McKenzie Thomas Buderwitz Soojin Lee Steven Young Drew Dalzell Scenic deSign coStume deSign Lighting deSign Sound deSign Joshua Marchesi Jamie A. Tucker* Production mAnAger StAge mAnAger musical direction by Dennis Castellano directed by Nick DeGruccio Dr. S.L. and Mrs. Betty Eu Huang Huang Family Foundation honorAry ProducerS corPorAte Producer Putting It Together is presented through special arrangement with music theatre international (mti). All authorized performance materials are also supplied by mti. 421 West 54th Street, new york, ny 10019; Phone: 212-541-4684 Fax: 212-397-4684; www.mtiShows.com Putting It Together• SOUTH COA S T REPE R TO R Y P1 THE CAST (in order of appearance) Matt McGrath* Harry Groener* Niki Scalera* Dan Callaway* Mary Gordon Murray* MUSICIANS Dennis Castellano (conductor/keyboards), John Glaudini (synthesizer), John Reilly (woodwinds), Louis Allee (percussion) SETTING A New York penthouse apartment. Now. LENGTH Approximately two hours including one 15-minute intermission. PRODUCTION STAFF Casting ................................................................................ Joanne DeNaut, CSA Dramaturg .......................................................................... Linda Sullivan Baity Assistant Stage Manager ............................................................. -

Academy for the Whole Child Charter School

ACADEMY FOR THE WHOLE CHILD CHARTER SCHOOL FINAL APPLICATION November 14, 2014 Respectfully submitted to the Massachusetts State Board of Elementary and Secondary Education Founding Group William Colonis John Russo Kim A. L’Ecuyer Kimberly Russo Elizabeth Hoeske Helen Obermeyer Simmons Emily Jermine Beverly Tefft Jennifer L. Jones Cecile Tousignant Jane A. Kennedy Concetta A. Verge Nancy Kerylow George E. Watts James McNamara Mary H. Whitney Josephine A. Rivers TABLE OF CONTENTS Information Sheet………………………………………………………………………………….4 Certification Statement……………………………………………………………………………..7 General Statement of Assurances for Massachusetts Commonwealth Public Charter School ……...8 Statement of Assurances for Federal Charter School Program Grant…………………………..…12 Executive Summary………………………………………………………………………………13 I. How will the school demonstrate faithfulness to charter? A. Mission ……………………………………………………………………….….17 B. Key Design Elements………………………………………………………….…17 C. Description of the Communities to be Served…………………………………....27 D. Enrollment and Recruitment……………………………………………….…….33 II. How will the school demonstrate academic success? A. Overview of Program Delivery…………………………………………………...34 B. Curriculum and Instruction………………………………………………….........41 C. Student Performance, Assessment, and Program Evaluation…………………......73 D. Supports for Diverse Learners…………………………………………………...80 E. Culture and Family Engagement…………………………………………………85 III. How will the school demonstrate organizational viability? A. Capacity………………………………………………………………………….91 B. Governance……………………………………………………………………...93